A review of The Disenlightenment: Politics, Horror, and Entertainment by David Mamet; 244 pages; Broadside Books (June 2025)

Take a look at the following sentence in David Mamet’s new book, The Disenlightenment, and see if you can make more sense of it than I can: “Today, the Left’s protestation of benevolence is everywhere unsaid by its real threat of immediate ruin.” Does Mamet mean to imply that the Left is opposed to benevolence? Or is he trying to say that the Left claims to be benevolent but is, in fact, nothing of the kind? If the latter, then what is in danger of immediate ruin? The Left? Benevolence? Protestations? And why does he use the word “unsaid”? Wouldn’t “undone” or “nullified” have made the sentence clearer? While I don’t subscribe to the Whorf-Sapir hypothesis, which holds that language constrains cognition, I do believe that muddled writing is often a symptom of muddled thought, and The Disenlightenment has plenty of both.

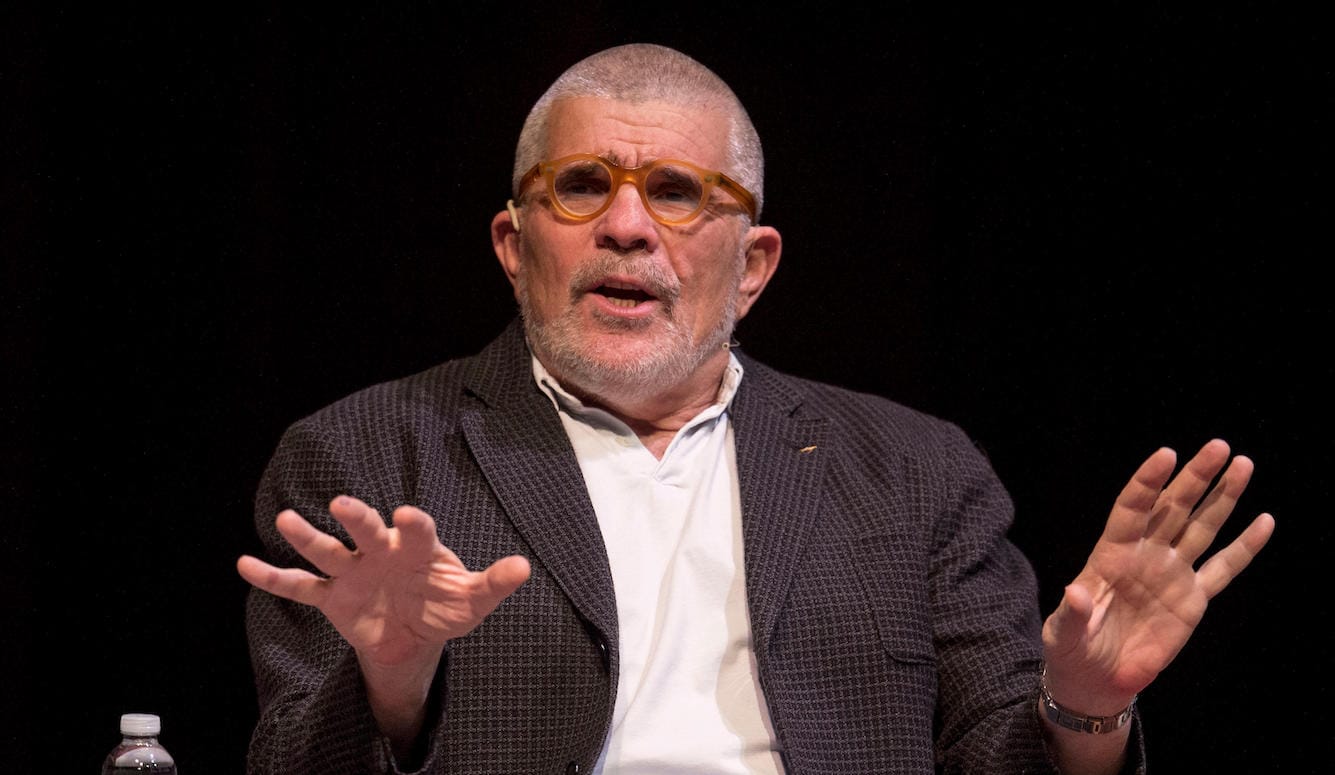

Mamet shouldn’t need much of an introduction. He is a prolific screenwriter and director, and probably the most successful American playwright of his generation—the author of Sexual Perversity in Chicago, American Buffalo, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Glengarry Glen Ross. And yet, as famous as he is for his dialogue—that staccato simulacrum of extemporaneous discourse known as Mamet-speak—he’s probably written more words for the eye than the ear. In the past forty years, he’s published over twenty books, including five novels, multiple essay collections, a collection of poetry, a memoir, and three volumes on politics: The Secret Knowledge (2011), Recessional (2022), and now, The Disenlightenment (2025), chronicling his transformation from NPR-listening liberal to MAGA conservative.

There is, of course, nothing unusual about this metamorphosis. “If you’re not a liberal when you’re 25,” Winston Churchill is supposed to have said, “you have no heart. If you’re not a conservative by the time you’re 35, you have no brain.” In all likelihood, Churchill never made that statement, but it continues to be quoted because it conveys a general truth about people: they tend to grow more conservative with age, either because they become eager to preserve what is familiar, or because they get mugged by reality, as Irving Kristol famously put it.

William Wordsworth’s shift from young radical to old Tory was set in motion by the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Whittaker Chambers quit the communist underground after learning about Stalin’s purges. In Mamet’s case, it was the sanctimony of the Left that drove him into the arms of the Right. “Have we turned into a nation of maiden aunts?” he asks in The Secret Knowledge. “The puritan has become, of late, the totalitarian, where every last thing, thought, and utterance in the Liberal Day must be an assertion of some Liberal Value; One-Worldness, Compassion, Conservation, Equality, the dread of giving offense, and guilt.”

Many of Mamet’s complaints are well-founded. I share his distaste for critical race theory, affirmative action, Antifa, didactic art, biological males competing in women’s sports, Hamas apologists on university campuses, the Los Angeles city government, and the “competitive masochism” of the Left in general. He’s right to discern a pseudo-religious dimension to the phenomenon known as wokeness. “Seventeenth-century sick young girls screamed ‘witchcraft,’” he writes in The Disenlightenment. “Their like today shriek ‘microaggression.’ What is the difference? There is none. They are both allegations that cannot be disproved. They are alleged by those claiming a supernatural ability to detect that hidden to the unawakened mind.”

But for every defensible claim like this one, Mamet makes at least two more that are ridiculous. “The nuclear family has been eviscerated,” he writes, “by technology, contraception, penicillin, travel, and so on.” If I squint, I can see why technology, contraception, and even travel are on that list, but penicillin? Since the drug was discovered in 1928, it has saved hundreds of millions of lives, thereby helping to keep countless families intact. Sometimes, it’s not even clear that Mamet understands the concepts he’s criticising. There are many good reasons to dislike intersectionality, the analytical framework conceived by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. It’s reductive. It’s prejudicial. And it relies on lazy stereotypes.

But these are not the reasons Mamet gives for opposing it. “‘Intersectionality,’” he writes, “is a word meaning ‘all of us want all of you dead.’” When I first read that sentence, I assumed that Mamet was simply exaggerating for effect. But two pages later, I came upon this: “Our two-party system has long been an example of intersectionality.” And a page after that: “‘You vote for my bridge, I’ll vote for your dam’ is intersectionality at its finest.” As anyone who has read Crenshaw’s work knows, none of these examples is an example of intersectionality, which is a method for measuring levels of social oppression among identity groups. “I’ve always known that words have power,” Mamet tells us in the book. In that case, he ought to be more careful how he uses them.

Mamet should also be more careful with his facts. Every nonfiction writer makes mistakes now and then. It’s impossible not to. But Mamet makes them on practically every page. Among other things, he claims that climate change isn’t real, that Japan doesn’t have auto unions, that COVID vaccines weren’t tested before they were given to the public, that the president of the United States is “constitutionally mandated” to greet foreign leaders when they visit the US, and that America didn’t enter the First World War until sometime after 1918, the year the war ended. That last error may just be a misprint, but with Mamet it can be hard to tell. In his 2022 book, Recessional, he alleged that Franklin Roosevelt’s economic policies “turned a bad month on Wall Street, in the most prosperous economy in history, into a decade-long worldwide depression.” Roosevelt didn’t become president until 1933, more than three years after the Wall Street crash, when the world was already in the pit of the Great Depression.

As a playwright, Mamet prides himself on his ability to see both sides of a conflict. “A good drama aspires to be and a tragedy must be a depiction of a human interaction in which both antagonists are, arguably, in the right,” he has said. When it comes to politics, though, he seems incapable of holding two opposing ideas in his head at the same time. In his telling, liberals aren’t just misguided; they’re “the enemy of Constitutional democracy.” “Obama was a Marxist and Islamist opportunist,” he informs us, “all his acts are recognizable as attempts to increase his personal power in order to achieve his personal and ideological goals.” Conservatives, on the other hand, are “citizen-workers, Americans, who adore our country,” led by a Capraesque hero whom Mamet compares to Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill:

President Trump influenced Americans as much by his attitude as by his policies. He had no time for outrage—he was fighting vicious opponents, and it was a waste of energy to keep reminding himself of their crimes—and his answer for defeatism was that his enemies could do whatever they wished, but he would never back down. He was not afraid of them, their lawfare, suits, slanders, or assassins. He’d thrown down his sash, and he was going to win or die, and either was acceptable.

People who only know Mamet’s work on the stage and the screen may find that passage out-of-character. As a dramatist, Mamet is allergic to idealism and hero-worship. In his artistic universe, there are two types of people: swindlers and suckers. “Don’t trust nobody,” Mike Mancuso (Joe Mantegna) warns Margaret (Lindsay Crouse) in House of Games (1987). That statement could easily be the tagline for Mamet’s entire oeuvre. His plays and screenplays are teeming with hustlers and mountebanks, from Donny and Teach, the petty thieves in American Buffalo, to Ricky Roma and Shelly Levene, the ruthless real-estate salesmen in Glengarry Glen Ross, to Jimmy Dell (Steve Martin), the slick trickster in The Spanish Prisoner (1997). For years, one of Mamet’s closest friends was the late actor and magician Ricky Jay, a great sleight-of-hand artist who taught Mamet about con games. “The confidence mark’s compliance is assured by maneuvering him from one scam to the next,” Mamet explains, “weakening his resistance by confusing him, and destroying his rational consideration through engendering compliance in addition to greed.”

The Disenlightenment came out this June, so Mamet can be forgiven for not mentioning the US$150 million jetliner that Trump accepted as a personal gift from the Qatari royal family or the private club that his son Don Jr. opened in Georgetown, selling access to the administration for US$500,000 a head, or the US$385 million Trump has acquired through his meme coin since returning to office, allowing favour-seekers an easy, unregulated way to put money in his pocket. But what about Trump’s many misdeeds during his first term in office? For instance, his refusal to place his assets in a blind trust or the approximately US$2 million he bilked from taxpayers to house Secret Service agents at his various resorts or his attempt, caught on tape, to get Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger “to find 11,780 votes” in order to overturn the 2020 election?

Mamet clearly dislikes public corruption. The Secret Knowledge, Recessional, and The Disenlightenment list numerous instances—some real, some imagined—of perfidy by Democrats, including Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley’s use of the police to frighten business owners in the 1960s, John F. Kennedy’s affair with a mafia don’s girlfriend, Bill Clinton’s lies under oath, Joe Biden’s pardon of his son Hunter, and the “murder” of Jeffrey Epstein. Does Mamet not see Trump’s self-dealing? Or does he simply not care about it? Before reading The Disenlightenment, I would have guessed the latter. Mamet has always had a fondness for reprobates. He once said that, if he hadn’t become a playwright, “it’s very likely I would have become a criminal—another profession that subsumes the outsider, or, perhaps more to the point, accepts people with a not very well formed ego and rewards the ability to improvise.”

And, like Trump, Mamet enjoys trolling. In the aftermath of the Clarence Thomas–Anita Hill controversy, when talk of sexual harassment in the workplace was ubiquitous, Mamet wrote Oleanna—a play later adapted for the screen by Mamet himself—about a male college professor who tries to help a female student, only to be falsely accused of sexually harassing her. By the end of the play, the initially vulnerable and distraught young woman has the professor by the balls. So it’s easy to see why Mamet, a lifelong admirer of street-smart, politically incorrect men, might be drawn to Trump—not in spite of his rough edges but, perhaps, because of them. The Disenlightenment, however, disabused me of this notion. Only a true believer could exhibit such naivety, unaware that his own words might come back to bite him.

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

The politician presents himself as uniquely qualified as the electorate’s doppelgänger, a champion against Evil—Batman, in effect. Politicians learn to incite rage, since voters, being human, may prefer it to the fear to which they have been incited as a preliminary.

And here’s another:

Politicians were once theoretically required to obey the laws they have sworn to uphold.

And another:

Legislatures and judiciaries ignore the letter and the spirit of Western law to persecute political opponents.

And another:

The universal indicator of tyranny, whether on the world stage or at the dinner table, is the inability to admit error.

And still another:

A story told long enough becomes, to the teller, true. That is not to say that it actually occurred as he remembers it, but that that is his belief. The macro-application of the principle is the Big Lie—that lie insisted upon by sufficient power, or broadcast over a long enough time to make disbelief inconvenient—either through fear of exclusion or reprisal.

Those, just to be clear, are all potshots aimed at Democrats. The fact that it never occurred to Mamet that they might ricochet back at Donald Trump shows you how narrow his political awareness is. In 2022, he wrote this:

The Constitution exists not to provide “unity” but to assert and demand the subjugation of unbridled interest to previously agreed-upon laws. Elected federal officials take an oath to uphold the Constitution. When they aren’t held strictly to that oath, we have that anarchy we see metastasizing around us. The constitutional oath must take precedence over party politics. [Italics in original]

And yet, Mamet won’t say an ill word about the sitting president—a man who, between his terms in office, called for “the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” Intellectual consistency has never been one of Mamet’s strengths. Recessional advertised itself as a defence of free speech, but it nonetheless criticised the American Civil Liberties Union for championing the right of Nazis to march through Skokie, Illinois, in 1977—a moment that free-speech advocates generally consider the ACLU’s finest hour.

The Disenlightenment is full of similar discrepancies. (Mamet has said in the recent past that all schooling—not just college—is a waste of time, and yet, in the new book, he chastises Greta Thunberg for curtailing her education to pursue climate activism.) All in all, it feels more like a series of social-media posts than a considered work of the intellect. “‘A firearm is 80 percent more likely to injure its legal owner than an intruder,’” he writes, quoting a hypothetical liberal opponent. “If so, why not issue firearms to burglars?” But of course, firearms are issued to burglars. The same laws that make it easy for homeowners to buy guns, make it easy for criminals to buy them, too. Mamet’s inability to orchestrate anything beyond hit-and-run assaults of this kind means that, even when he attacks soft targets, he inflicts little damage. “How did defunding Israel benefit trans-activists? Or banning fracking increase African-American economic status?” he asks. Who’s claiming that they did?

The New Yorker critic Anthony Lane once remarked that while Mamet’s plays were like bulls, his films were like eels, always slipping through your fingers. If I were to extend the metaphor, I’d say that his books are like mosquitoes. When I finished the final page of The Disenlightenment, I experienced the same sense of relief that I feel when I swat an irritating insect that has been buzzing in my ear all night. In a 2011 review of The Secret Knowledge, Christopher Hitchens observed that one of the most annoying things about the book was its “pointlessly aggressive style.” In the fourteen years that have passed since The Secret Knowledge was published, Mamet’s writing has, if anything, only become more aggressive. Back then, he was merely accusing Jane Fonda of treason. Now, he’s accusing Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Kamala Harris of having engineered a “coup” in 2020. The title of the new book, The Disenlightenment, is clearly meant to be an accusation. Taken in context, though, it reads more like a self-description.