philosophy

Do Androids Dream?

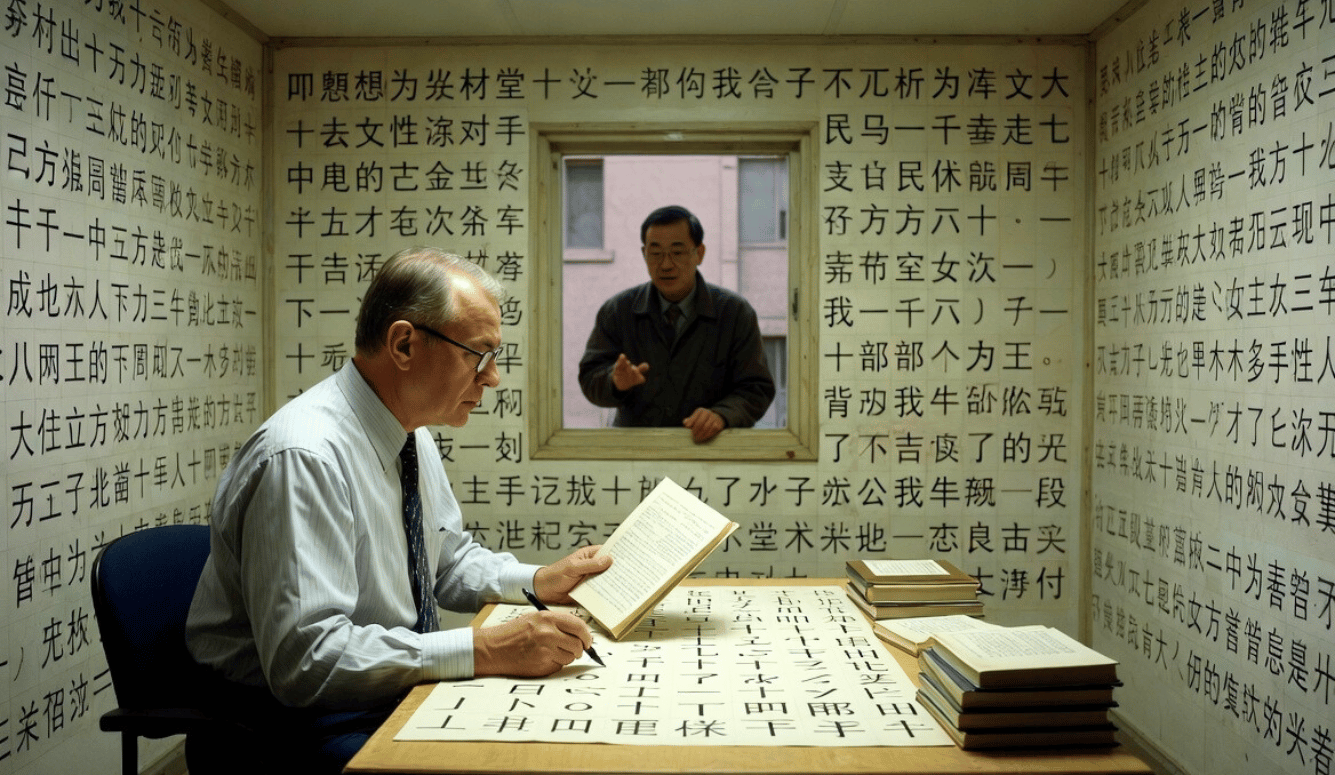

The philosopher John Searle’s concept of Intentionality and his Chinese Room experiment reveal the differences between AI computation and human thought.

John Searle, one of the preeminent philosophers in the Anglophone tradition, died late in September. Ironically, the man who coined the distinction between “institutional facts” and “brute facts” expired under a cloud of institutional condemnation, stripped of his title of emeritus professor by the University of Berkeley on the grounds that he sexually harassed a graduate student in her twenties when he was in his eighties.

The distinction between brute facts (which relate to the physical world) and institutional facts (which relate to things that only exist if humans agree to believe them) is articulated in Searle’s 1995 book The Construction of Social Reality. Examples of institutional facts include money, marriage, property, and government. As Searle puts it:

Institutional facts are so called because they require human institutions for their existence. In order that this piece of paper should be a five dollar bill, there has to be the human institution of money. Brute facts require no human institutions for their existence.

One could say similar things about employment and institutional titles such as emeritus professor.

Searle notes that we need the institution of language to state a brute fact but the fact stated needs to be distinguished from the statement of the fact. He defends realism (the idea that there is a world independent of our thought and talk) and the correspondence theory of truth (the idea that whether or not our statements are true depends on whether they correspond to how things are in this real world that exists independently of our statements about it). Realism about the world and a correspondence theory of truth, he says, are “the essential presuppositions of any sane philosophy, not to mention of any science.”

Searle’s early books, Speech Acts (1969) and Expressions and Meaning (1979) contributed to the philosophy of language. His later works Intentionality (1983) and The Rediscovery of the Mind (1992) developed his approach to the philosophy of mind. He rejected the “dualist” idea that “mind” and “matter” are “distinct substances.” Instead he defended a position he called “biological naturalism,” which is simply the view that mind is caused by and arises from evolutionary processes in nature. A key component of mental activity as he describes it is “Intentionality.” His 1995 work, The Construction of Social Reality, and his 2010 book, Making the Social World, drew on his earlier work on language and mind to develop an account of how human agreement is required to construct social reality. Overall he made significant contributions to the philosophy of language, the philosophy of mind, and social ontology.

His writing is characterised by clarity, crispness, and boldness. His 2004 book, Mind: A Brief Introduction gives an example. Explaining why he wrote it Searle says:

[T]he philosophy of mind is unique among contemporary philosophical subjects, in that all of the most famous and influential theories are false. By such theories I mean just about anything that has “ism” in its name. I am thinking of dualism, both property dualism and substance dualism, materialism, physicalism, computationalism, functionalism, behaviourism, epiphenomenalism, cognitivism, eliminativism, panpsychism, dual-aspect theory and emergentism, as it is standardly conceived.

I do not propose to explain all these “isms” in detail but they are all still used in debates about “mind” and “the hard problem of consciousness.”