European Union

A Shrivelling Continent

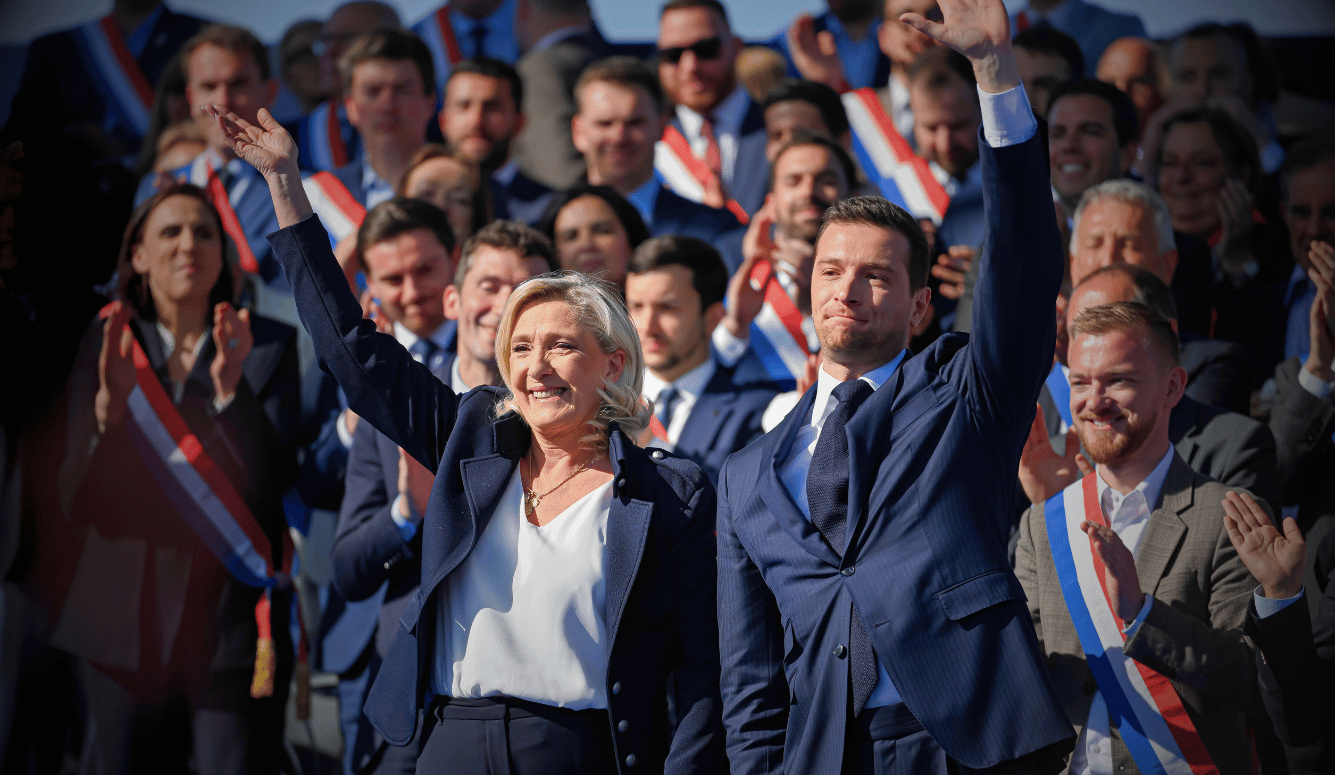

As the nationalist parties of the New Right gain ever greater influence in Europe, the future of the European Union is looking increasingly precarious.

As the nationalist parties of the New Right gain ever greater influence in Europe, the future of the European Union is looking increasingly precarious.

It is not right to say that Europe is leaderless—but there is much less confident leadership here than we have been used to, and the problems our senior politicians have inherited are proving hard to tackle. If this situation continues, the pre-eminent role Europe has played in world affairs for centuries will be seriously weakened, and the European Union itself might become an irrelevance.

The EU is accustomed to coping with challenges on various different fronts, especially from those who believe that its existence is an affront to sovereign democracy. Brussels has long been able to brush such criticisms aside. “Why can’t they see how necessary we are?,” is often the basic response. “Don’t they understand that clinging to the nation state in an age in which borders are becoming increasingly irrelevant is a response of the purblind?”

But now there has been an outcry from those who fear that the people who are clinging to the idea of the nation-state have been gaining the upper hand. The most urgent calls to action have been voiced by three politicians—Mario Draghi, Enrico Letta, and Romano Prodi—each of whom was once prime minister of Italy. Post-war Italian politics has often been dismissed as passionately disordered and fundamentally unserious, yet now Italy is the key site of the struggle over Europe and trends in that country have been pointing the way that others will be constrained to take. What we are witnessing is a struggle in which established politics is losing ground to a new way of thinking.

The frustrations expressed by the retired premiers at the workings—or non-workings—of the EU illustrate the predicament in which all the EU member states find themselves. All three Italian politicians believe deeply in the Union—more, perhaps, than the leaders of any other large state. They know that their country needs the EU’s backing to enable its economy to remain viable, dependent as it was and is on German industry, the export of luxury goods, and a helpful European Commission. They also hoped—and believed—that at some future time a European government would take control of Europe’s macroeconomy and defence, as well as assuming other governing powers still to be determined. They would have viewed this as a progressive development.