Crime

Britain Must Be More Honest With Itself

In a country struggling to come to terms with violent acts by recent immigrants, the dark mistruths of bigots have been replaced with the cheerful mistruths of multiculturalists.

When I visited Britain at the end of October, I was often annoyed by its rail services. Over a long weekend, three trains were late and one was cancelled. Spatial constraints meant being crammed into a carriage like a sardine in a can. To top it off, the experience was brutally expensive (Britain has some of the most expensive fares in Europe). It was a relief to step off my last train—which is quite something when I was about to enter Luton Airport.

Alas, a week later, an incident in eastern England put my petty grumbling into perspective. An unhinged black British man attacked travellers on a Peterborough to London train with a knife and left eleven people with serious injuries. Passengers fled through the carriages to escape the man—or hid in toilets and the buffet car. The quick-thinking driver stopped at Huntingdon station, which facilitated police access.

The authorities are now investigating whether the attacker can be linked to several earlier knife-related incidents—in which a fourteen-year-old boy was stabbed and in which a barber’s shop was repeatedly menaced. This, in turn, could raise questions about why the attacker was free to begin with.

This comes after several other horrifying recent events: the murder of a random binman out walking his dog by an Afghan national and the murder of a Jewish man at a synagogue by a suspected jihadist who was born in Syria. Confidence in the authorities was also shaken—where it existed at all—by the accidental release of an asylum seeker who had been convicted of sexually assaulting a teenage girl. The bemused Ethiopian man appears to have been as baffled as anyone by his release—taking a leisurely train journey to London without making any obvious attempts to hide or flee.

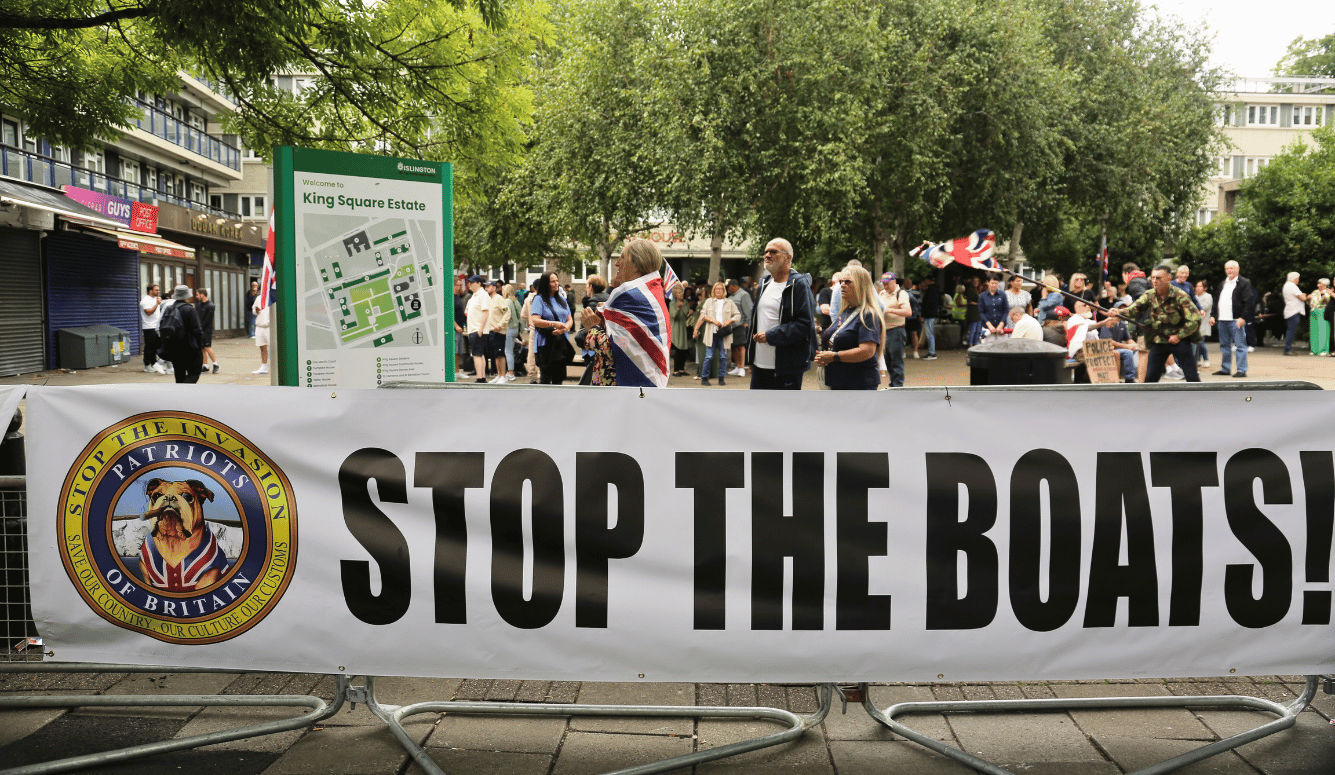

The national mood is anything but optimistic. Prime Minister Keir Starmer is the most unpopular PM on record, and while this has a lot to do with Britain’s bleak economy, the success of Nigel Farage’s right-wing populist party Reform UK suggests that it also has a lot to do with British discontent regarding the effects of mass migration. Right-wing activism like Operation Raise the Colours—which saw Union Jacks and St George’s Crosses blooming across British streets—and protests outside hotels that had been earmarked for asylum seekers have also been symptoms of widespread dissatisfaction.

Faced with a clear sense of national decline, some journalists have been hurrying to make the point that overall violence has declined in Britain. That is true. As Noah Carl argues, factors like population ageing, declining alcohol consumption, and an increase in the incarceration rate make this unsurprising. As I have argued elsewhere, though, there has also been a rise in indiscriminate, sensational, violent, public events, which naturally have a bigger hold on people’s imaginations than “normal”—if often no less tragic—violent events. It is also the case that a disproportionate amount of this violence is being committed by non-EU migrants and their children—something that makes people resent a decades-long, consistently unpopular liberal immigration policy.

Compounding popular frustration is the sense that the cultural and political establishments are more disturbed by the potential responses to violent events than by the events themselves. The horrific Manchester Arena bombing, which killed 22 people in 2017—many of them young girls—and was perpetrated by a Libyan jihadist was followed by the resurgent popularity of the Oasis song “Don’t Look Back In Anger” (this prompted Morrissey, formerly of The Smiths, to sing on “Bonfire of Teenagers,” “I can assure you I will look back in anger till the day I die”).

The use of the Oasis song might have had organic roots. But it has also been revealed that the British state attempts to frame public responses to terroristic and otherwise violent events by manufacturing what some “contingency planners” call “controlled spontaneity.” “The purpose of the operations,” writes Ian Cobain of Middle Eastern Eye, “is to shape and direct public responses, encouraging individuals to focus on a sense of unity and empathy for the victims, rather than reacting with violence or anger.” For example, following the London Bridge attack of 2017, a government official is alleged to have phoned the local council with a promise to send “a hundred imams.”