Art and Culture

Out of the Past

A new book looks back on the making of Billy Wilder’s American classic.

A review of Ready for My Close-Up: The Making of Sunset Boulevard and the Dark Side of the Hollywood Dream by David M. Lubin, 336 pages, Grand Central Publishing (August 2025)

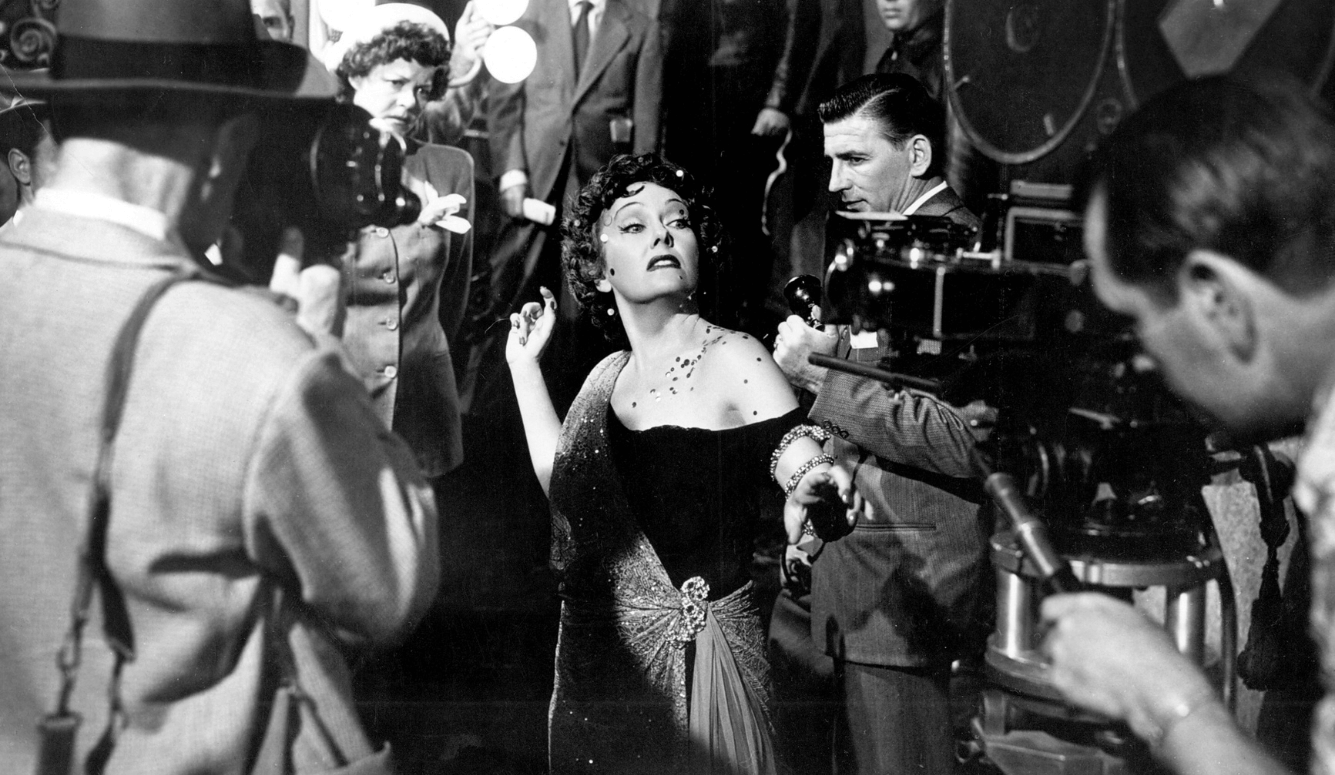

Billy Wilder’s 1950 film Sunset Boulevard is difficult to categorise. It can be described as a tragedy, a film noir, a melodrama, a whodunnit, a gothic horror tale, a wisecracking and self-referential Hollywood satire, or all of the above rolled into one. The antiheroine of the story, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), loathes words because talkies robbed her of her career in silent pictures (“We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces!”) And yet, the film gives her some of American cinema’s most memorable lines, including the one David M. Lubin lifts for the title of his new book, Ready for My Close-Up.

Rather than writing a straightforward production history—comparing various drafts of the screenplay and explaining which scenes were shot when—Lubin provides us with a series of mini-biographies of the people who made the movie, including Wilder and his writing partner, Charles Brackett; the two lead actors, William Holden and Gloria Swanson; and half a dozen supporting players, among them Erich von Stroheim, Cecil B. DeMille, Hedda Hopper, and Buster Keaton. All of these people have received full-length biographies from other authors, so Lubin’s book sometimes feels like the CliffsNotes version of their lives. He says of DeMille, for instance: “He died in 1959, proud of his integral role in the commercial, if not artistic, history of Hollywood.” In fact, DeMille (who plays himself in Sunset Boulevard) had plenty of artistic achievements to be proud of—The Cheat (1915) and The King of Kings (1927) are two of the finest films of the silent era. Presumably, Lubin is referring to DeMille’s later films—like Samson and Delilah (1949), the picture he’s seen directing in Sunset Boulevard—which were pure popcorn flicks.

Still, Lubin does a good job of tying the various stories together. By the time Sunset Boulevard came out, Wilder and Brackett had been working together for more than a dozen years, starting with Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938), which they cowrote for director Ernst Lubitsch. They were an odd couple. With his chubby cheeks and impish grin, Wilder looked like a Little Rascal in adult form, hiding his thinning hair beneath a fedora he rarely removed. Born in 1906, on the fringe of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he gave up a lucrative career in the German film industry when Hitler came to power, fleeing Berlin the day after the Reichstag Fire. “It seemed to me,” he later explained, “the wise thing for a Jew to do.” With the help of a friend, he landed a job in Columbia Pictures’ writing department, despite the fact that he barely spoken any English. Fortunately, he was a quick study, learning the language (or so he claimed) by listening to soap operas and baseball games on the radio. Wilder’s family—his mother, his stepfather, and his grandmother—remained in Europe and perished in the Holocaust.

Brackett’s family, on the other hand, had lived in America since the 1620s. His great uncle George Henry Corliss built the Corliss Steam Engine, which powered factories all around the world. After graduating from Williams College in 1915, Brackett served in the American Expeditionary Force’s diplomatic corps in France. His father, a New York State senator, wanted him to take over the family-owned bank, but Brackett, who had begun publishing short stories in the Saturday Evening Post, yearned to be a writer. In 1926, Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, hired him to be the magazine’s drama critic after Herman Mankiewicz left to try his hand at screenwriting in Hollywood. Six years later, Brackett followed Mankiewicz there. The first couple years were tough. “Though basically in agreement with the reviews, I resent them hotly,” he confided to his diary, after one of the films he’d written was savaged by critics. “May God give me strength never to accept a really silly project again.” It was only after he was teamed with Wilder that he began to enjoy his work. Together, they wrote Ninotchka (1939) and Ball of Fire (1941), two of the most delightful romantic comedies of the period.

Despite his blue-blooded pedigree, Brackett always played second fiddle to Wilder, who was eager to begin directing pictures as well as writing them. In 1942, Paramount gave Wilder the green light to direct his first Hollywood feature, The Major and the Minor. This was followed by Five Graves to Cairo (1943), Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), The Emperor Waltz (1948), and A Foreign Affair (1948), all of which Brackett co-wrote and produced, with the exception—a big exception—of Double Indemnity. By the late ’40s, though, the relationship was starting to curdle. Wilder could imagine a life without Brackett more easily than Brackett could imagine a life without Wilder. Five months before production began on Sunset Boulevard, Wilder announced that it would be their final film together.

It’s a good thing Wilder didn’t terminate the partnership sooner. While the two men got on each other’s nerves, they also balanced each other out. Brackett curbed Wilder’s cynicism and tamped down his zaniness. Wilder initially wanted Norma Desmond to be played by Mae West, the bawdy, big-breasted star of She Done Him Wrong (1933). Fortunately, Brackett talked him out of it. Though he didn’t use the word, which hadn’t come into use yet, Brackett could see that West was too camp for the movie they were making. Casting her as the female lead would have turned the film into a broad comedy, not, as Brackett put it, “a picture of distinction.” Instead, they went with Gloria Swanson, who made Sunset Boulevard her own.