Politics

The Language of Independence

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s doctrine of self-reliance has been corrupted by social media, wellness culture, conspiracy theorists, and the “sovereign citizen” movement.

In 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson, leader of the New England transcendentalist movement, published an essay about the importance of cultivating self-reliance. Emerson wanted each individual to make their own moral compass of greater importance than the rules imposed by the state and society. It was a credo that demanded the individual remain steadfast against institutional tyranny and the creeping interference of government.

Emerson’s essay became one of his fledgling nation’s most influential texts, tapping into an American belief in a rugged individuality that hoped to dispel notions of old-world conformity, tradition, and aristocratic servitude. Emerson was unambiguous: “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.” He was not recommending reckless contrarianism but moral independence rooted in personal conscience. This doctrine found itself at home in the American imagination and was espoused in spirit and action by contemporaries like Abraham Lincoln and future statesmen like Theodore Roosevelt.

In fact, it’s hard to think of a text better suited to American ideals. Emerson’s high-minded exhortation to cultivate one’s own mind and body, and to live what Roosevelt called the “strenuous life,” is central to American exceptionalism. In time, these ideas spread far beyond the United States, and their proponents included Winston Churchill, who adopted the language of individual dynamism to frame his own exploits and visions of how a man should live and exist as a citizen.

While Emerson’s epitomes endure in the modern day, they have been besmirched by the dynamics of social media and the groupthink that these platforms encourage and enable. Instead of upholding the virtues of independence and the clarity that one can derive from listening to the inner voice that Emerson originally promoted, much of what is peddled on social media drowns out anything resembling individuality or critical thought.

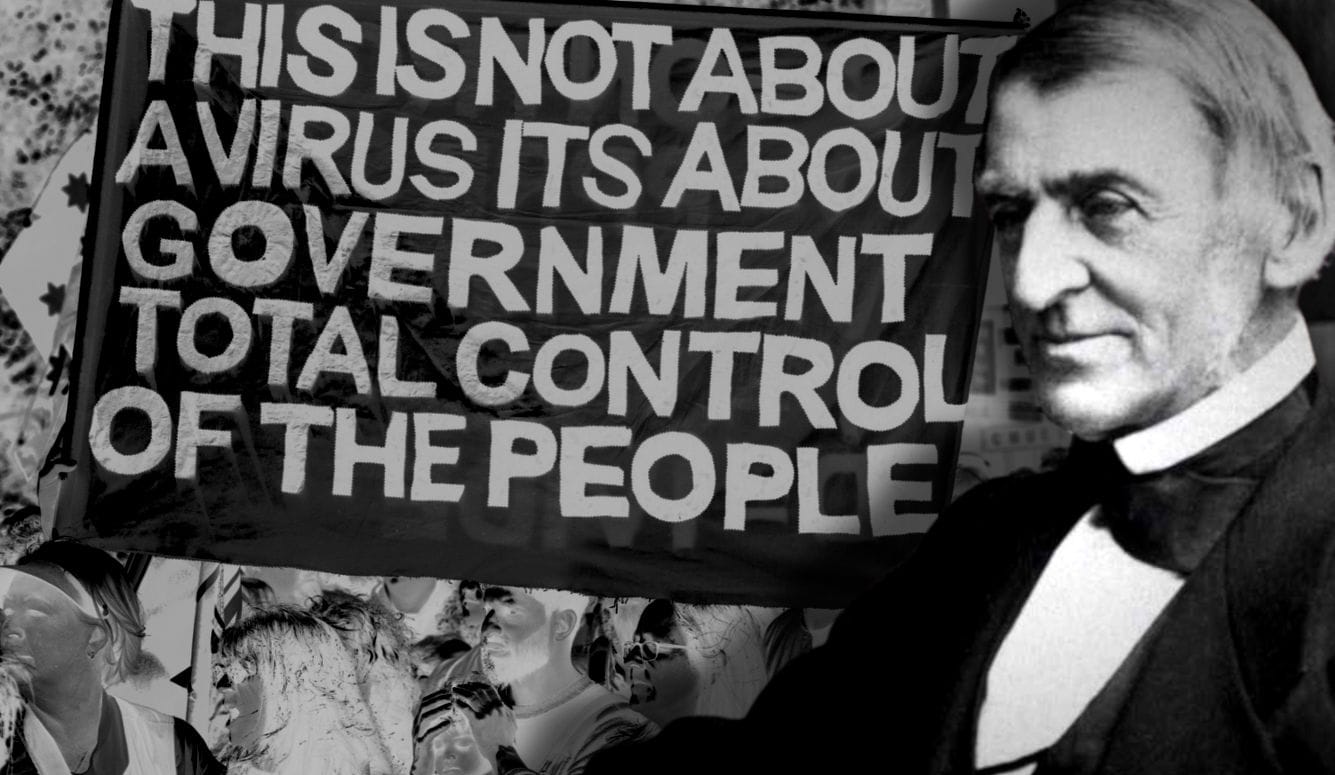

Online wellness communities often use the same natural metaphors that Emerson employed, invoking flowers, seasons, water, and sunlight as symbols of inner balance and growth. Where Emerson used the rose, the wave, or the river as images of authenticity and becoming, online wellness discourse recycles similar imagery to promote practices of self-care and anti-institutional wellbeing. But wellness culture’s reflexive anti-authoritarianism creates fertile ground for conspiratorial thinking and followers primed to embrace narratives of government control, overreach, and medical cover-ups in pursuit of profit. “Whoso would be a man,” Emerson declared, “must be a nonconformist.” But in the age of social media, this dictum has metamorphosed into contrarianism for its own sake, where rejecting authority becomes more important than discerning truth.

Amid the messy confusion of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people—jobless, imprisoned at home, and angry that their liberty was being sacrificed in the name of collective safety—shifted from pursuing natural remedies and self-care to embracing anti-vaccine beliefs and broader conspiracies about global elites. As a result, wellness ideas intended to encourage ownership of personal health and self-determination became suspicious of anyone who claimed to be an arbiter of health or law. Social media was pivotal in enabling these grievances to fester like mismanaged diabetic wounds. With twisted Emersonian ideas, a number of influencers moved into niche conspiratorial territory. This atmosphere of paranoia and hostility toward institutions provided the perfect conditions for fringe movements such as so-called “sovereign citizens” to develop.

Australia’s sovereign-citizen movement follows Emersonian ideals of self-reliance and individuality to their most fanatical conclusion: that a man is a law unto himself, and that there is no authority more supreme than the individual. The very notion of collective order becomes despotic, and the concept of making decisions for the benefit of the whole becomes illegitimate. Emerson himself wrote, “No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature,” yet where Emerson compelled men to follow their own conscience before robotic conformity, sovereign citizens reject the notions of civic responsibility and government altogether. Committed to ill-founded ideas of what freedom is, they may even take sovereignty to its most violent conclusion, as we have recently witnessed in Victoria:

Choppers whir overhead. Kevlar-clad officers methodically patrol the town. Armoured vehicles roll down its streets. Porepunkah is now the centre of a massive manhunt for a heavily armed man that police allege murdered two of their own in cold blood.

Officers went to Dezi Freeman’s property on the outskirts of the rural Victorian town on Tuesday, with a warrant to search it. They were met with gunfire, before their alleged attacker—a “sovereign citizen” with a well-documented hatred of authority—vanished into nearby bushland.

The shooting—which appears hauntingly similar to an ambush of police in Queensland three years ago—has shocked the town and revived questions over how the country deals with growing sects of anti-government conspiracy theorists.

Granted, any legal system is, at its core, a belief system. As Yuval Harari reminds us, lawyers are modern-day shamans, weaving binding narratives that hold only as long as enough people believe in them. The difference between the fringe sovereign-citizen movement and common law is not one of kind but of degree: the latter commands legitimacy simply because it has far more adherents and its belief system is backed by state power.

What actually unites sovereign-citizen groups is not raw Emersonian self-reliance but a diluted version unmoored from its ethical foundations. All that remains is a profound distrust of anyone perceived as standing “above” them. Their stance is less an ethic of independence than hostility towards authority in any form. External direction is considered illegitimate, regardless of whether it comes from health officials, government, or other institutions. The underlying logic is closer to childish insubordination—“you are not the boss of me”—than it is to a coherent philosophy of freedom. It is anti-establishment to the core, defined not by what it builds but by what it refuses to acknowledge.

Social media, by its very design, amplifies this kind of juvenile insolence. Its mechanics reward defiance, self-dramatisation, outrage, and antagonism, turning rejection of authority into a performance that attracts visibility and validation. Under these conditions, what begins as posturing on social media, outbursts of fury, and an anger at perceived loss of control over one’s life can rapidly escalate, feeding conspiratorial delusions and, in some cases, even violent acts of terror.

Perhaps these new manifestations of self-reliance should be understood less as deliberate distortions of Emerson and more as coping mechanisms in a world far more complex and confusing than his own. Emerson wrote at a time when the boundaries between the self and society or government and citizen were contested but clearer. For the government to exercise control over the citizen, it had to come knocking. Today, individuals are confronted with complex and overlapping economic, digital, and bureaucratic systems that are omnipresent, opaque, and apparently unaccountable. In such an environment, clinging to a façade of sovereignty, whether through wellness rituals, conspiratorial thinking, or pseudo-legal fantasies, offers a sense of clarity and control. It is not Emerson’s conscience-driven independence, but it does answer a similar human need: the desire to feel that one’s life is not wholly at the mercy of forces beyond one’s own control.

There remains something romantic in Emerson’s original call to self-reliance. It still resonates because it speaks to a deep human desire for dignity, conscience, and independence of thought. But in our age of global connectivity, rapid exchange of information, and interwoven systems, self-reliance alone cannot serve as a sufficient ethic. We face collective challenges—climate change, pandemics, mass migration, technological disruption—that no sovereign individual can overcome in isolation. If Emerson gave us the language of independence, our moment may demand a new language of interdependence. Acknowledging our reliance on one another does not require us to abandon autonomy, only to situate it within a wider recognition that freedom itself depends on the health of the collective.

It remains to be seen whether the rabid individualism promoted by social media and its influencer foot-soldiers can be recalibrated to support collective flourishing rather than splintering into atomised, niche, and often conflicting ideals. But I suspect Emerson himself would look upon modern interpretations of self-reliance with dismay.