Quillette Cetera

Leaving the Woke Cult with Anthony Rispo | Quillette Cetera Ep. 52

Heterodox psychology grad Anthony Rispo joins Zoe Booth to unpack leaving woke ideology and the psychology behind identity, conformity, and belief.

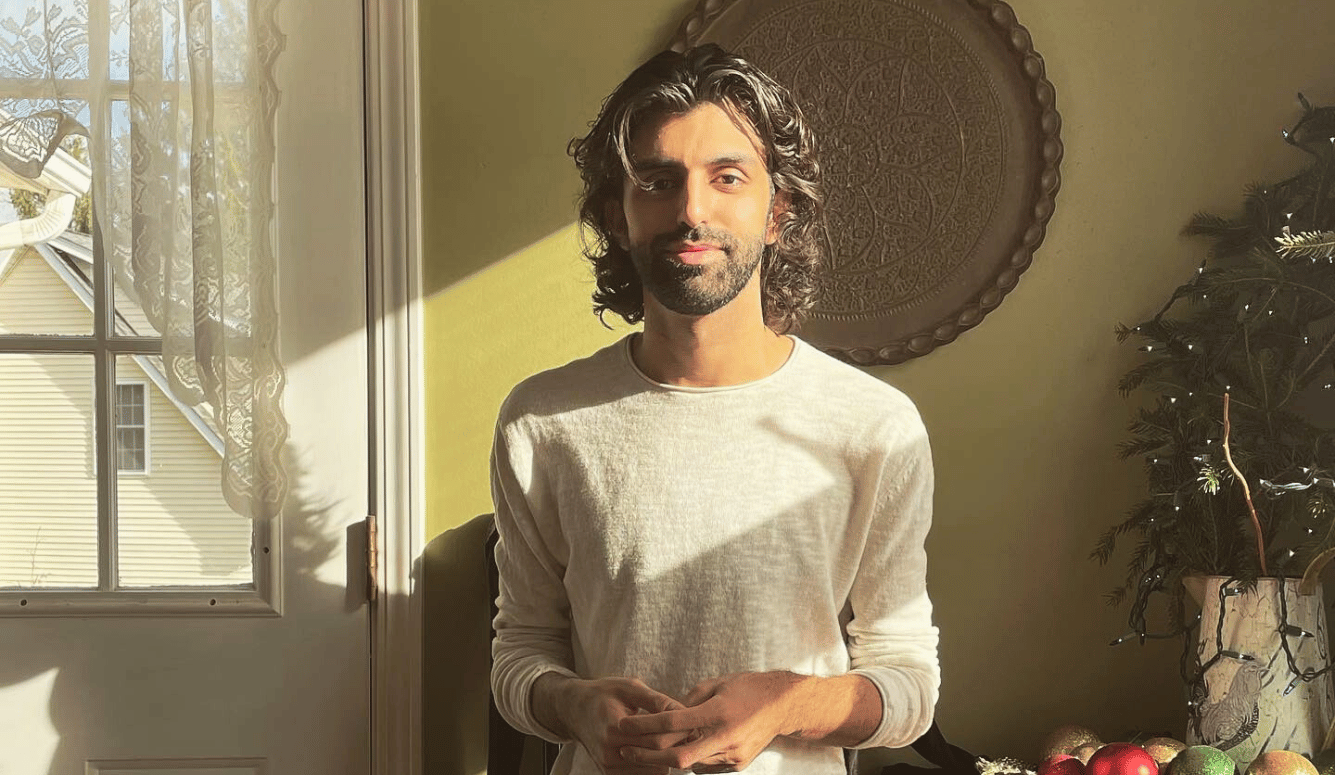

In this episode of the Quillette Cetera podcast, host Zoe Booth is joined by Anthony Rispo—a writer, independent researcher, and co-host of The Discourse Lab podcast. Anthony holds a degree in psychology from Columbia University, where he specialised in social cognition and sociopolitical behaviour. His academic research has explored narrative, perspective-taking, and autism, and he founded Columbia’s Heterodox Academy Campus Community to promote open inquiry and viewpoint diversity.

Zoe first discovered Anthony on Instagram, where he shares nuanced, carefully reasoned commentary on culture and politics. His platform offers thoughtful, accessible videos on everything from identity and political behaviour to social psychology and group dynamics.

In this conversation, Zoe and Anthony reflect on their own journeys through highly ideological phases—Anthony as a gay man in activist circles, and Zoe as a self-described vegan Marxist feminist. They discuss how those beliefs affected their personal lives, particularly family relationships, and what it took to step back from those frameworks while still extending empathy to those who remain within them.

Transcript

Zoe Booth: I have so much to talk to you about. I think we have a lot of crossover in our interests—and maybe our stories as well. We’re a similar age. I think you just turned 35?

Anthony Rispo: Yeah, 35 in December.

ZB: I’m thirty. I’m not sure if you used to be on the Left—I get that vibe, maybe?

AR: Yeah. I say that with such concern in my tone. Well, I guess without giving the whole story from childhood onwards—although I think a little bit of reference is good—I grew up in a fairly... I wouldn’t even say it was a political household. I’d say, in retrospect, moderate. Close to New York City, about fifteen minutes north of Manhattan, on the border of the Bronx and Manhattan.

So, a lot of diversity—cultural, ethnic, religious. I went to a public school in my primary years—well, what you’d call primary school. But my really formative years were at a Montessori school, actually, up until third grade.

That’s where I was exposed to... it was like the United Nations for a child. All different types of—yeah—kindergarteners. I’m obviously kidding, but that’s what I remember: all colours, types, and backgrounds.

ZB: Can I ask about your background? I was trying to place “Rispo”—could be anything.

AR: I know, yeah—it’s ambiguous. A lot of people guess I’m Italian. My father’s from Naples, and my mum’s side is Sicilian—well, paternal side Sicilian, maternal side... yeah. I get mistaken for Middle Eastern all the time. I got Spanish the other day—from Spain—and I’ve even been taken for French once. It’s a whole mix, but there’s some truth to that because all those countries invaded southern Italy.

ZB: Exactly.

AR: So I was exposed to a diversity of people. Long story short, I switched to Catholic school in fourth grade—more homogeneous: Italian, Polish, Catholic. Then we moved further north—just about an hour up—and I went to a public high school.

I was fifteen when we moved. And through all that time, I didn’t really engage with politics. I had a bit of a shift in my religious views. I grew up very Catholic—still moderate, not extreme about it. But it’s funny—thinking of this off the cuff—I had a modification in how I thought about religion around age sixteen. That went in tandem with how I was starting to think about sexuality, identity, and who I am as a person.

Other than that, when I first started voting, Obama was the first president I voted for. That’s when I was on the Left. But of course, looking back, it wasn’t quite the same as what we think of now—but in some ways, it was.

ZB: I am going to pick up that thread of sexuality if you’re comfortable talking about it, because one of the ways I discovered you on social media is through my best friend, who’s gay. He’s a very—what we’d say here—based gay man, who, over time, has taken issue with a number of the ideological orthodoxies he’s felt pressure to go along with in gay spaces.

He sent me a few of your reels, and I saw that you speak publicly about being gay, and about the ideological groupthink in those spaces. Would you like to say a bit more about your experience with that?

AR: Yeah. It’s funny, because it’s not the sexuality part that’s uncomfortable—none of it is uncomfortable to talk about. It’s just that it’s like an alternate reality. We came from this entire culture—or we’re still in it—this fog of leaning into identity and obsessing over it. And now, to do a post-hoc on it...

We don’t have to do anything, but I look at my identity from a different lens. I try to extract, pull apart, and understand why, years ago, I attached myself to that groupthink model. And in doing so, you need a metacognitive approach: okay, I’m gay—that’s obvious. But what does that mean for me now, with this new take on things?

You start asking, “How does that interact with my—” and then you think, “Wait, am I talking about intersectionality?” But of course, some of these concepts do have validity. We all have aspects that aren’t monolithic. But to segue from that: being monolithic was exactly the problem. I treated myself and thought of myself in that unilateral way—I’m gay, therefore I must adhere to these principles and mandates.

And I never liked drag. I couldn’t really spot why. Now I know—at a base level, it’s not my thing. But I also think it’s a mockery of the feminine. It’s a caricature. That’s my very strong view. So—okay.

ZB: I love drag. And maybe it’s because I see the humour in mockery as well. I don’t see it as mockery, but imitation. Though I can see how it could be offensive in certain circumstances. I think, in particular, if drag queens or the people who attend those shows go on to express views about gender ideology or biological women that I find unpalatable—that’s more offensive, that combination of both.

AR: Right. We see some of that in the gender world now. But yes, I understand that perspective. I can understand why someone would enjoy it, and from a distance, I can get on with it a little. I’ve been to a few drag shows. For me, it was more about introspection—pulling away from that scene and looking at the double standards.

You have people who are pro-women’s rights and very vocal about femininity—but then they’re using womanhood in this caricatured way. So maybe my view is a bit extreme, but it’s part of my analysis. I also never really considered myself someone who latched onto identity—group identity—even in terms of my heritage.

My father is a huge football fan—soccer, depending on where you are—and so is my brother. I know it’s popular worldwide, but I never got into it. Growing up, I’d see him go nuts when his team won. It was all about Italy and regional teams. But I just never understood that. I never latched onto identity.

So being in gay spaces—or even clubs in my twenties—I always felt out of place, paradoxically. I never felt comfortable.

ZB: Mm-hmm. Yeah, I’ve been thinking about this a lot. I’ve had similar experiences—not being a gay Italian man, obviously—but I identify as a gay Sicilian man.

So I grew up in a pretty working-class white area of Australia, but funnily enough, despite being obviously very, very white, I always felt a little bit—as we would say here—woggy. That term can be used offensively, but in Australia, wog essentially refers to Greeks, Italians—any sort of Mediterranean peoples.

I’m half Greek.

AR: There’s a word for it. Wow. Okay. Okay—go on. I feel what’s happening. I won’t use it, though.

ZB: Don’t go around using it willy-nilly! In the UK, it’s extremely offensive. Here, it depends on the context—it can be pejorative, but it’s not really anymore. It’s a very light pejorative.

But my mum is an Australian-born Greek. And I went to Greece and realised, wow—we are so not Greek. But still, I felt a little bit different, and I did feel a connection to a culture. And I’ve always been—and it’s funny that I say a culture, like Australia doesn’t have one—but in many ways, I think Australia does. And maybe the US as well. But white people there do seem to feel a lack of culture.

And to come back around to this—we recently had, just this past Sunday, quite a huge pro-Palestine march across the Sydney Harbour Bridge. It was approved last minute. It had to go through the courts because they were using perhaps our biggest landmark for a political cause—a very divisive one that a lot of Australians don’t necessarily support.

And I saw these kids—well, adults now—from Newcastle, white kids. And part of my analysis for why they were there—maybe it’s cynical—but it just seemed like they were getting a sense of culture, and community, and belonging out of joining what is essentially a pan-Arab nationalist decolonisation movement.

Obviously, they’re not Arab. But I see fewer kids from, say, Chinese families or other communities with a strong cultural identity getting involved in those sorts of protests. What do you think of my theory?

AR: Yeah—no, this is great. I’ve been thinking about this a lot. There are so many different points to address.

Well, the first point—going back to the idea of culture among white people in America: I think there are some regions, especially in the South and Appalachia—if I’m pronouncing that right—where there’s a very strong sense of cultural identity. It just depends on where you are.

In more urban, metropolitan areas—where you have a lot of progressive types, yuppie types, or whatever term you want to use—you get a very different kind of white person. Often, they’re transplants. They’ve moved into the cities from elsewhere.

And my observation is that these people, psychologically and sociologically, don’t have as strong a connection to their heritage, lineage, or cultural background. I don’t want to generalise—because I don’t know if there’s empirical research on that—but just from observation, there’s a big difference between those in rural America and those in cities.

You can see this reflected in electoral politics too—the Republican Party being traditionally associated with middle America. That’s changing now, but for a long time, it was true. So that divide shows up in voting patterns as well.

Moving on to your main point: I think you’re right that it tends to be white liberals who fuse with causes like the Palestinian cause. Politically and sociologically, that’s always been the case—since Johnson, the Great Society, and the Civil Rights Movement. You had white liberals jumping on board, supporting civil rights, free love, all that.

There’s an interesting demographic distinction when it comes to white people and cultural identity in America. And I think it’s worsened by decades of admonishing traditional American identity—of castigating the white American. Whiteness has been turned into a symbol of inherent oppression—like a moral original sin. Something you can’t fix, but that’s always there.

We saw this play out from the 1960s to 2015 and during the BLM movement. And now there’s this fascinating piece of psychological literature I came across called “identity fusion.”

Identity fusion is the visceral sense of oneness with a group, where your personal identity and the group’s identity are functionally the same. So, a threat to the group feels like a personal threat.

And they’ve found that people can fuse not just with their in-groups but with out-group causes too. For instance, American students—white American students—fusing with Palestinians. There was research done on UK and US students (mostly white), and it predicted a willingness to engage in extreme activism for causes unrelated to their personal identity.

ZB: Wow.

AR: Yeah. So, the idea is that they’re attaching themselves to causes that don’t belong to them—like the protest you mentioned—because of this identity fusion.

They believe that what they’re fighting for in the out-group relates to some issue they identify with. So university students see themselves as fighting against the patriarchy, or against Western civilisation. And they transpose that onto the Palestinian cause. They view Israel as the oppressor, America as the oppressor, the West as the oppressor. So they fuse their identity with those they perceive to be oppressed.

It’s a long-winded explanation, but that’s the psychological mechanism I’m exploring at the moment.

ZB: Yes, it’s fascinating. And I think, you know, being gay or being a woman, you can see some similarity—there is some truth to intersectionality. You can feel that your group, even as a woman, is sometimes discriminated against by the patriarchy. And so you transplant that onto Israel–Palestine.

But I do wonder... One of the guys who comes to mind is a straight white guy from Newcastle who’s suddenly very into this topic—geopolitics wasn’t even on his radar before. I think for him, it’s probably more of a mating strategy, to signal to the kind of women he wants to attract—probably university-educated, intellectual women—that he’s a good mate, because he cares deeply about the current thing.

AR: This individual—he organised the protest...?

ZB: He didn’t organise it—he just attended and was virtue signalling that he was there. It was all very public.

AR: Ah, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head—virtue signalling. There are a few things going on.

I’m living in this dissonant space right now, because I don’t want to be absolutist. And that’s not out of fear of coming across one way or another—it’s for my own mind and sanity. I genuinely want to try and get this right.

So, I think it could be true that he genuinely cares—he may have an orientation towards harm and care, that moral axis. Maybe he’s temperamentally a little more feminine. I don’t know him, so I don’t want to speculate—but research suggests liberal types tend to have that proclivity toward nurturing and caring. And at the most pathological end of that, you can get a sort of overbearing or controlling dynamic—wanting to impose their view of care onto the world.

But anyway, it could also be virtue signalling. Or it could be something darker. There are certain individuals—especially those high on what’s called the Dark Tetrad of personality—who will insert themselves into these moments for selfish reasons.

ZB: Mm.

AR: For those who aren’t familiar, the Dark Tetrad includes narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism.

Narcissism being the inflation of one’s ego. Machiavellianism is treating people as a means to an end—charming them into doing things for you. Psychopathy is a lack of empathy—coldness. And sadism is taking joy in the suffering of others. Somewhere in there, too, is general antagonism.

So there are people who posture as morally righteous but are actually driven by darker motives. Especially some predatory men—they know exactly what they’re doing. They’re operating from that dark personality profile.

Or, like I said earlier, he could just be someone who genuinely cares deeply and has a slightly more feminine temperament. The research does support that possibility too.

ZB: Yes, fascinating. I did want to talk to you about those personality traits, because you speak about them a lot on your channels. And you’re a neuroscience student—is that right?

AR: I just graduated from Columbia with a degree in psychology. They treat their psychology department very much like a neuroscience department, so I spent a lot of time doing neuroscience research. That’s what got me interested in going below the surface—to understand the more mechanistic aspects of behaviour. What’s happening in the brain, that kind of thing.

ZB: Yes—fascinating. And I’ve heard you talk about the Light Triad. What’s that?

AR: That’s a great one. One of my professors, Scott Barry Kaufman, came up with the concept. He recently wrote a fantastic book called Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization, and his newer one, Choose Growth, touches on similar ideas—about moving past victimhood and into growth.

Anyway, the Light Triad is essentially the opposite of the Dark Triad. Where the Dark Triad includes narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—sometimes with sadism added—the Light Triad includes Kantianism, humanism, and faith in humanity.

Kantianism is treating people as ends in themselves—not as means to an end, like Machiavellianism. Humanism is valuing the dignity and worth of every individual. And faith in humanity is the belief that people are generally good and trustworthy.

Scott developed a scale to measure this in about 2019. People who score higher on the Light Triad tend to report greater life satisfaction, more compassion, more empathy, and lower levels of aggression, manipulation, and exploitation.

It’s not that people fall neatly into one category or the other—actually, the beauty of this construct is that you can measure both. Someone might score high on one element of the Dark Triad and also on one of the Light Triad dimensions. It gives us a more holistic, nuanced picture of the human condition, rather than just pathologising behaviour all the time.

ZB: Mm. Yes, it’s fascinating. Lately I’ve been very concerned about social media and how much of our communication now happens through it. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on the psychology behind that.

I feel like—at least with topics like Israel and Palestine—there’s a saturation going on. I read recently that the ratio of pro-Palestinian to pro-Israeli content online is about 15 to 1. So people are being marinated in this content every day. I don’t like to use the word brainwashed, but it does feel like constant exposure—and it does have real-world ramifications.

So when I say I’m pro-Israel, or that my fiancé is Jewish and has family in Israel, it triggers something in people’s brains that’s been shaped by what they’ve seen online. And I think that’s very frightening.

AR: Yes. Okay—so I think at the heart of it, it’s not even just confirmation bias. That might be part of it, but I believe something even more fundamental is going on.

It likely starts with temperament—how someone sees the world—and their moral convictions. That is, how they experience their beliefs as moral imperatives: non-negotiable, resistant to compromise. There’s often some cognitive rigidity involved.

Now, that rigidity can be adaptive in certain contexts—especially when we’re negotiating or navigating social life. Even if it’s just implicit, we’re often referring back to our moral convictions. And when something contradicts those beliefs, we get an autonomic stress response. A signal goes off: something’s wrong.

How well someone regulates that stress response will determine what happens next. If someone’s high in anxiety or neuroticism—or has trouble with ambiguity—then things can escalate quickly. That goes for people on either side of this issue, by the way. I’ve seen it happen with both pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian supporters.

So much of it comes down to how someone deals with conflict—and how fused they are, psychologically, with the issue. That fusion will often determine whether the interaction leads to hostility or whether there’s space for reasoned discussion, empathy, and genuine exchange.

It’s such a complex mix of baseline temperament, emotional regulation, and—essentially—biology.

There was actually a great piece published by you guys—Quillette. I saw it on YouTube and it was by Claire Lehmann—

ZB: Yes, the founder of Quillette—my boss.

AR: Yes! How embarrassing that I didn’t remember the name right away. But yes—she did a piece on the radicalisation of young women. So, she said something that really struck me. Women aged 18–30 are now roughly thirty percentage points more progressive than men of the same age.

Psychologically, I think that’s really interesting. Women tend to be slightly higher in trait neuroticism—and people hear that and immediately assume it’s a negative thing. But it’s not. It’s actually adaptive. It includes things like vigilance, care, sensitivity to threat—particularly useful for raising children.

ZB: Yes—for looking after children, perceiving threats, that kind of thing.

AR: Exactly. And male vigilance is often driven more by testosterone and physical aggression. It’s a different mechanism. So there are sex differences, and they’re real. They’re biological. And they’re adaptive—not something to be ashamed of.

But if you have someone who’s higher in trait neuroticism, who has a history of adverse life experiences, and who is going through adolescence or early adulthood—and then you introduce social media? You’re going to get a magnified effect.

Social media dramatically shortens the reward response time. It’s constantly stimulating the dopaminergic system. So if someone is feeling uncertain or anxious, they may seek assurance by scrolling or posting—and then get rapid reinforcement from a like, a comment, a shared belief.

Even if what they’re doing is harmful or unhealthy, they’re being positively reinforced in real time. And they’re surrounded by a like-minded digital community. So it becomes very difficult to break out of that.

So yes—social media isn’t the cause, per se. But like Jonathan Haidt argues brilliantly, it’s a major moderator. Whatever is already there gets amplified. Especially for adolescents, who are by nature exploratory and curious—it’s like throwing petrol on a fire.

I was just interviewed on a news network here in the States—Newsmax. I’m not sure if you know it?

ZB: Sounds familiar.

AR: Some people here see it as very conservative. But anyway, I was asked about this backlash to a jeans commercial—Sydney Sweeney talking about her genes. And a bunch of progressive women came onto TikTok saying it was fascist, or problematic in some way.

And I said the same thing—it’s not social media itself, but that social media accentuates the underlying disposition of the person. If you already have those sensitivities, social media rewards them and entrenches them.

ZB: Yes. I actually had a piece published today in Australia’s Financial Review about Sydney Sweeney. And I had to get up to speed on it, because—well—every week there’s a new scandal. And often I opt out if I don’t think it’s worth my time. But I was asked to write about this, so I thought—okay, let’s have a go.

I analysed it from a few key angles. One of them was intrasexual competition. I don’t think it’s the whole story, but I do think it’s a part of it. She’s a very good-looking woman, and I think a lot of the women attacking her—who I believe were mostly women—were engaging in reputational attacks. That’s what women tend to do—attack each other’s reputation from afar.

Also, Sydney’s a registered Republican and comes from a so-called “MAGA” family—which is apparently a crime. So that was clearly a factor.

AR: Yes—reputation savaging.

ZB: Exactly. And she’s also not afraid to be classically attractive. She doesn’t try to downplay it with piercings or tattoos or a severe haircut—like Billie Eilish or Zoë Kravitz might do. Both of whom are stunning, but who also try to subvert traditional beauty standards.

And I felt that myself, actually, during my radical feminist phase. I’ve always had a pretty classical appearance—white, thin, whatever. And I tried to downplay that. I cut my fringe really short. It was a way to signal that I belonged to this radical group.

AR: That makes sense, yes. A sense of belonging. And it’s interesting that you say that—well, not just interesting, but worth noting—that both of us went through those phases and came out of them.

I’m still trying to pinpoint the exact moment it shifted for me. I think it was gradual, definitely gradual. But it involved confronting moments of dissonance—things not adding up.

I think when you’re dealing with a lot of distress, it can feel comforting to outsource your autonomy to a group. And I’m not saying that was the case for you, but I know for me, I had those moments of distress, and it felt good to just hand over that autonomy to something collective, amorphous.

Earlier in the conversation I said I didn’t even feel like I belonged to those groups, but it was still comforting to know they were there. There’s something cathartic about it. Therapeutic, even. You can distance yourself from your own issues.

Now, there’s a difference between being part of a pro-social group—something positive and constructive—and becoming part of something rigid and dogmatic. Once things start to coagulate, you find people in those spaces who may be psychologically oriented in more pathological directions.

And that doesn’t mean they’re broken forever. It just means they’re in a certain season of life. That’s how I think about some of the students I saw at Columbia—tying themselves to fences, protesting.

I was in class, hearing helicopters overhead, sirens, people shouting. I understood some of what was happening from a distance, but I knew I could never go where they had gone. And that’s not me saying I’m better than them—it was just a distinction I noticed in myself.

For me, it started around the time of George Floyd. I remember losing it at my brother because he didn’t post a black square on Instagram.

ZB: Did you? Wow.

AR: Yes. I’ll say it very publicly. I think it’s important. I talk a lot about the Left, and I criticise the Left, but I don’t talk enough about my own story. I haven’t wanted to centre myself too much, but it’s important for context.

My sister had just given birth to my niece. We were in the hospital two days later. The baby was undergoing some tests—routine stuff—and my brother and I started talking about politics.

He had voted for Trump. I got so activated. I started yelling in the hospital room.

I vividly remember the black square conversation. At one point, I was upstairs in this space—where I am now—moving things around, and my brother was downstairs. We got into it again and I just exploded.

And afterwards, I thought: “What is wrong with me?” I get chills thinking about it.

So I can’t say for sure what everyone else is experiencing when they do things like that, but I imagine many of them are going through something similar. Emotion dysregulation.

ZB: Yes. I’ve had similar experiences. Two in particular come to mind—where I got really angry and stormed out of conversations.

One was with my aunt. She’s not university-educated or anything like that, and she mentioned “boat people”—I don’t know if that’s a term you have in the US?

AR: No.

ZB: Right. Well, obviously, we’re an island, and “boat people” is what we used to call illegal immigrants who arrived by sea. It’s not a very creative term, and it eventually became pejorative.

This was around 2008, when we were experiencing waves of illegal migrants from places like Malaysia and Indonesia. And at that stage, I was very young and completely immersed in progressive ideology.

I remember being disgusted by her language. I really lectured her on why she couldn’t use that term.

And now, it seems so obvious—of course it’s a bad idea to have unknown people just arriving in your country unvetted. But back then, I couldn’t see it.

AR: Right. Exactly. Isn’t it wild? And we were told this all along—well, not directly, but the common-sense perspective was always there. It’s amazing.

ZB: Yes. The other time was around Caitlyn Jenner—when she was on the cover of Glamour, I think, and was named Woman of the Year.

Someone at my university said, “She’s a man,” and I was so appalled—publicly appalled. I really went after him, called him a transphobe, and made it a public issue.

But I remember how I feigned outrage. It wasn’t genuine offence—I realise that now. It was that I had the upper hand. I had power over him, and I used it.

It’s gross to admit, but I think it’s important. I wasn’t upset. I was performing power—using my moral outrage as leverage. That’s what it was.

AR: That’s so interesting—the power thing. I think a lot of it comes down to that. And when you dig into the power dynamic, you uncover a deeper need for control.

It’s about closing the gap—the psychological discomfort we feel when things are ambiguous. We all experience that feeling. But how we respond to it depends on where we are emotionally, psychologically, socially.

That feeling of needing to correct someone, to say something righteous—it often stems from this inner drive to close the gap between what we expect and what’s actually happening.

That sense of, “I’m being attacked,” or “This is a moral emergency.” And again, back to identity fusion—if you’re deeply fused to the issue, any disagreement feels like an attack on you personally.

I’ve also noticed a concerning trend recently—on some of these YouTube channels that are clearly conservative, often religious, usually Catholic. I’ve seen a few guests advocating for a return to conversion therapy, or promoting these outdated theories that say insecure attachment causes homosexuality.

That’s insane. It’s completely unfalsifiable. There’s no scientific validity to that.

AR: I think if we’re going to talk about “woke” as a totalising mindset—something that’s punitive, moralising, and demands compliance from others—then yes, we absolutely have to criticise it.

But there’s a parallel happening now on the Right that’s just as troubling. For example, this idea that homosexuality necessarily results from poor attachment or childhood insecurity—that’s pseudoscientific. And just like the Left’s use of “whiteness” as an original sin, this narrative on the Right also becomes metaphysical and unfalsifiable.

It’s essentially psychotic reasoning, and yet it’s being platformed. You can’t argue with it using logic or data, because it’s not grounded in either.

I posted something recently on Instagram, saying: people expect me to be even-handed, and yes, we still have to discuss all the ways in which the Left has become censorious and punitive. But there’s this new, ugly undercurrent emerging on the Right. And it’s serious.

They’re conflating homosexuality with gender ideology—and those are two entirely different things. Gender dysphoria, or “gender identity” as it’s now framed, involves a lot of additives. You have to change pronouns, medicalise the issue, and often encroach on others’ rights.

For example, in the US, under Biden—but it actually began before him—Title IX was updated to say that if you misgender someone more than once, that could be considered harassment, punishable with significant penalties.

In New York City, in 2015, there was a policy saying if you misgender someone once, that’s a mistake. Twice, maybe still a mistake. But by the third time, it could result in a $250,000 fine. I’ve read the actual PDF. It’s real—and it’s absurd.

But none of that applies to homosexuality. You’re not required to do anything for me just because I’m gay. You don’t have to marry me in your church. You don’t have to like me. I’m fine with that. The Ministerial Exception protects churches in the US—they can hire and fire without explanation in many cases, and that’s protected under the separation of church and state.

Gender ideology is a different beast. It requires participation, affirmation, often legal compliance. And I really don’t like how these things are being lumped together.

ZB: Yes. You see a lot of that—on both the Left and the Right. But especially on the Right now, where all these issues are being conflated. Like with Jews, too.

There’s this narrative that Jews somehow “brought in” gender ideology—or that Jews are responsible for all the ills of progressivism.

It’s so frustrating because both of us have very clear, rational gripes with woke ideology. We see the problems. And we find ourselves agreeing with some of these people on the Right... right up until they say: “And it’s because of the Jews.”

That’s where I’m like—no. I’m not with you there. That’s a hard stop for me.

AR: Yes, exactly. I had someone comment on one of my Instagram posts recently. I was talking about identity fusion again—this time in relation to a CNN story about a trans woman in Colombia who had been killed in broad daylight.

I criticised CNN for covering that but ignoring the systemic violence against queer people in the Middle East. And someone commented “woman?”—with a question mark, as if to challenge the term trans woman.

And I’m like—come on. That’s not the point. I’m not affirming their identity in some metaphysical sense. It’s a term of classification for communication. It’s the language that allows us to even talk about the issue.

But people get stuck on semantics. And I’m just not going to go there with them. I’m not going to let that derail the discussion.

ZB: Exactly.

AR: Anyway, I think the last thing I’ll say on this—well, actually, I’ve already lost my train of thought! But maybe to summarise: we’re in a bit of a quagmire right now. We’re standing on very difficult terrain, socially and culturally.

We don’t really know where we are. Everything feels very unsettled. And it’s hard to navigate because we’re still in the thick of it. We can’t zoom out yet.

ZB: Yes, I feel the same. I often wonder if I’m just too online—and if I spent more time offline, I’d probably feel better. And I’m sure that’s true.

But at the same time, we don’t know where we are until we’ve gone through it and can look back with some perspective. And right now, it just feels like a very scary, very weird time.

AR: I agree. I think about that too—am I just too online? But then I look at what’s happening in New York City. I see Zohran Mamdani, the mayoral candidate. Maybe he’s a digital phenomenon, sure. But his success is a reality.

People feel unsafe. Even if the data says crime is down, the perception is different. The migrant crisis is real—it’s not imagined.

So I think we are seeing these things in real time. It’s not just that we’re online too much. It’s happening.

ZB: Yes, definitely. And here in Australia as well. Some of my Jewish and Israeli friends say, “It’s not that bad. If you got off social media, you’d see it’s not as widespread.” That we’re just seeing the worst of antisemitism online.

But I say: a car was literally firebombed on the street next to mine—because a Jewish leader used to live there. So it is a reality.

I’m constantly having this internal debate: How bad is it really? Am I being paranoid?

But then there’s lived experience—and even beyond that, just trying to engage socially. Like joining a group, or going out to meet new people... We went to a pub trivia night the other week, and even that devolved into a debate about Israel–Palestine.

It’s just constantly there—especially in left-wing spaces. If you go to any kind of arts or cultural event, it’s always lurking. It feels inescapable.

And talking about fusion again—this is a topic I am fused with, unfortunately. I feel like it has real-life consequences for me, my family, my future children. It feels incredibly personal.

And I know for a lot of these protesters, it’s not personal at all. It’s just a cause. But for me, it’s intimate.

Do you have any psychological advice on how to deal with that? Because I don’t want to get so upset. It’s exhausting.

AR: Oh, I feel that. And I’m not a clinician, so I want to be cautious. But just from one human to another—and as someone who’s done a lot of work on my own anxiety—I’ll share a few things.

First, there’s the “need for closure”. That’s a real psychological term. And it’s related to the need for control, which is heightened when ambiguity is present. For people who are more anxious or sensitive to threat, that ambiguity is stressful. The brain wants to know.

So, what helps is quieting the mind as much as possible and mentally rehearsing various scenarios: “If this happens, what will I do?” “What if that happens?”

Not in a panicky, neurotic way. Not with a chart on the wall and string connecting ideas like a conspiracy theorist. Just a gentle priming of the brain—giving it some predictability, so the ambiguity isn’t so threatening.

When we experience something that conflicts with how we’ve constructed the world, it can trigger what’s called a “prediction error.” The brain is always anticipating what’s going to happen next, and when something defies that expectation, we get dysregulated.

If your baseline anxiety is low, it’s usually fine. If it’s high, the reaction is proportionately more intense. And if it’s extreme, it can even become trauma.

So, preparing the mind—lightly—is helpful. And then there’s another tool I like: the space between stimulus and response.

There’s a quote often attributed to Viktor Frankl—though it may not be his—but it goes: “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

That’s the work. Creating a pause. That’s how we regulate our autonomic nervous system, our prediction mechanisms. We don’t react immediately. We allow reflection and metacognition to take place.

So, on one hand, we want to widen the gap between stimulus and response. But on the other hand, we want to close the gap of ambiguity. Those are two different strategies.

Widen the space for reaction, and close the space of uncertainty by giving your brain some predictability.

I hope that’s not too convoluted. They’re slightly conflicting ideas, but if listeners can disentangle them, I think it’s helpful.

ZB: No, that’s very sound advice. Thank you.

We’ve been going for an hour now. Is there anything else you’d like to talk about before we wrap up?

AR: Just very briefly—I regret not leaning more into your earlier question about sexuality. I think the only thing I’ll add is that I’ve noticed more and more lesbian, gay, and bisexual people—especially gay men—pushing back against gender ideology.

And I don’t have much to say beyond: I saw this coming. And I think the pushback is only going to grow stronger.

For me, I just hope we can sort this all out rationally and peacefully. That we can talk to people who are in distress and who are genuinely struggling, and maybe weed out the bad actors who aren’t acting in good faith.

There are people in the trans community and in the broader LGBTQ+ space—and in the woke Left—who are where we were once. And I want us to remember that.

It’s easy to forget where we used to be. But we need to remember that there are people out there who are malleable, who can wake up to using their own minds. And if we can be there for them—not by moralising, but by example—that matters.

Don’t just repudiate who you used to be. Be an example for others who are still there.

ZB: That’s a beautiful sentiment. I completely agree.

As people who have been through it ourselves, we do need to show more empathy. It’s very easy to get caught up in that feeling of: “Well, I saw the light—why haven’t you?” Or “I grew out of it by that age—what’s wrong with you?”

AR: Yes, yes. “How dare you not see the light?” It’s hard. It’s something I work on. But yes—

ZB: —or, “I was already past this at your age!”

AR: Right, right, right. It’s tricky. But it’s a practice.

ZB: Well, Anthony, thank you so much for joining me today. It’s been a real pleasure talking to you.

AR: Thank you for having me, Zoe. It’s been such a pleasure—and an honour. I love Quillette. Thanks again.

ZB: Great—I love what you do too. And yes, we’ll definitely have to do this again. There are so many more topics we could get into.

AR: That would be great. I’d love that.