I. Three Illiberal Fronts

Over the past two decades, three kinds of extremist movement have shifted from the fringes of public discourse to the political mainstream in various parts of the world. The first of these is the authoritarian New Right, which is “postliberal” and nativist in character. The Trump administration in the US and Viktor Orbán’s regime in Hungary represent this trend, as do a range of far-right parties in Europe, India, Russia, Latin America, and elsewhere. The second is the postmodern “anti-colonial” Left, which has long been influential in Western academia, but has also recently secured an influential political presence in a number of places. The radical wing of leftist parties in France, Britain, the US, and elsewhere represents this trend, and it operates in close alliance with Islamist movements, which constitute the third front. Islamists hold power in several Middle Eastern and Asian countries, and they have also established a highly effective presence in Western Europe and North America.

Although these three movements differ in many ways, they also share significant features that allow us to see them as variants of a common response to a major social crisis.

All three promote the interests of identity groups rather than the interests of an economic class or social-issue coalition. For the New Right, the relevant identity is that of the resident majority population, which they believe is threatened by immigrants and minorities seeking to displace them. The postmodern Left agitates on behalf of the indigenous or formerly enslaved victims of European colonialism, and a multiplicity of gender groups said to be oppressed by the white patriarchy. Islamists wage jihad against Western society and its Muslim collaborators on behalf of oppressed Muslims.

All three are animated by the grievances of their respective constituencies, for which they hold urban Western liberal elites responsible. They target these elites as the agents of the misfortunes that afflict their supporters, and their grievances are frequently accompanied by elaborate conspiracy theories about who controls the press and the levers of power. Each presents itself as the voice of outsiders advocating for the dispossessed in a way that is misleadingly described as “populist.” All three believe that science, objectivity, and fact-based reasoning are instruments of social control employed by their oppressors. They justify their own claims by invoking ideological narratives, the “lived experiences” of victims, and certain revered texts as the authentic basis of political understanding. They rely heavily on social media and informal digital networks for recruitment and propaganda purposes.

Notwithstanding their declared wish to improve the lot of humanity, not one of these movements is progressive in the traditional sense of seeking to build on the achievements of the past through reform or revolution to create a more equitable and rational social order. On the contrary, all three are reactionary and backward-looking. They seek to reclaim a mythic past destroyed by the corruptions of contemporary Western civilisation. The New Right wants to return to an era of social harmony and prosperity, which they imagine prevailed before the influx of large numbers of foreigners and the acceptance of permissive social norms. The postmodern Left wishes to reclaim the purity of pre-colonial indigenous cultures, pre-patriarchal equality, and the health of the natural world prior to the industrial assault on the environment. Islamists seek to restore the ascetic lifestyle of the Prophet Muhammad’s rule and the early years of the Caliphate, before the West—and even the high culture and science of Medieval Islamic empires—subverted this divinely decreed order.

To obtain a clearer perspective on the extremist tide that is currently engulfing our societies it would be helpful to consult an earlier historical precedent.

II. The Romantic Counter-Enlightenment

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the European Enlightenment replaced religious belief with rational scientific enquiry as the epistemic basis for understanding the natural world. Enlightenment thinkers like Locke, Voltaire, and Kant sought to ground social institutions in reason rather than tradition, and they laid the foundations for modern political liberalism by advocating universalism, rationalism, and self-criticism. Classical liberalism held that objective knowledge of the natural world is possible, and that social arrangements can be optimised according to the requirements of reason.

A strong Romantic reaction against the Enlightenment emerged in the latter half of the 18th century and gathered support during the 19th. The epistemic perspectives of Romantic poets, artists, musicians, and philosophers emphasised subjective experience and the inner emotional life as the only reliable source of knowledge. They rejected rationalism and the primacy of science, and many of them saw the industrial revolution as a destructive force that threatened the integrity of the natural order. This led to an anti-urban celebration of rural environments and a return to nature, explored by Isaiah Berlin in his 1965 Mellon Lectures The Roots of Romanticism.

Romanticism inspired a number of distinct and often incompatible political movements. It was a driving force in the unsuccessful liberal nationalist uprisings of 1848, which attempted to replace several of Europe’s aristocratic regimes with free democratic states. Some of the alumnae of these failed revolutions, however, moved on to blood-and-soil ethnonationalism in the latter part of the 19th century. Wilhelm Marr, a former 1848 democrat who coined the term antisemitism to describe his subsequent political program, founded the Antisemite League in 1879 and published The Way to Victory of Germanism over Judaism. Georg Ritter von Schönerer had cooperated with Viktor Adler, the Jewish founder of the Austrian Social Democratic Workers Party, on the Linz programme for Austrian German national independence. But by the end of the 1880s, von Schönerer was a rabid pan-German nationalist campaigning against Jewish refugees seeking shelter in Austria from East European pogroms. Karl Lueger, mayor of Vienna from 1897 to 1910, also moved from liberalism to right-wing Catholic antisemitism. The Nazis used his civic government, which combined anti-Jewish racism with expansive public works and housing projects, as a model for their welfare fascism.

That ethnonationalist strand of Romanticism led directly to fascism and Nazism, and it provides a clear antecedent to the more extreme sections of the New Right today. In the original version of their conspiracy theory, the Jews are identified as a vagrant Middle Eastern people, who infiltrated and corrupted Western societies for their own gain. The current iteration of this idea holds that Jews use their financial power and media influence to manipulate Europeans and North Americans into importing immigrants and subverting the native social order. This was the motivating view of the attacker who carried out the Tree of Life Synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh on 27 October 2018, which killed eleven people and wounded six more. The nativist Right is promoting a second-order replacement view, with Jews as the financiers and organisers of the threat.

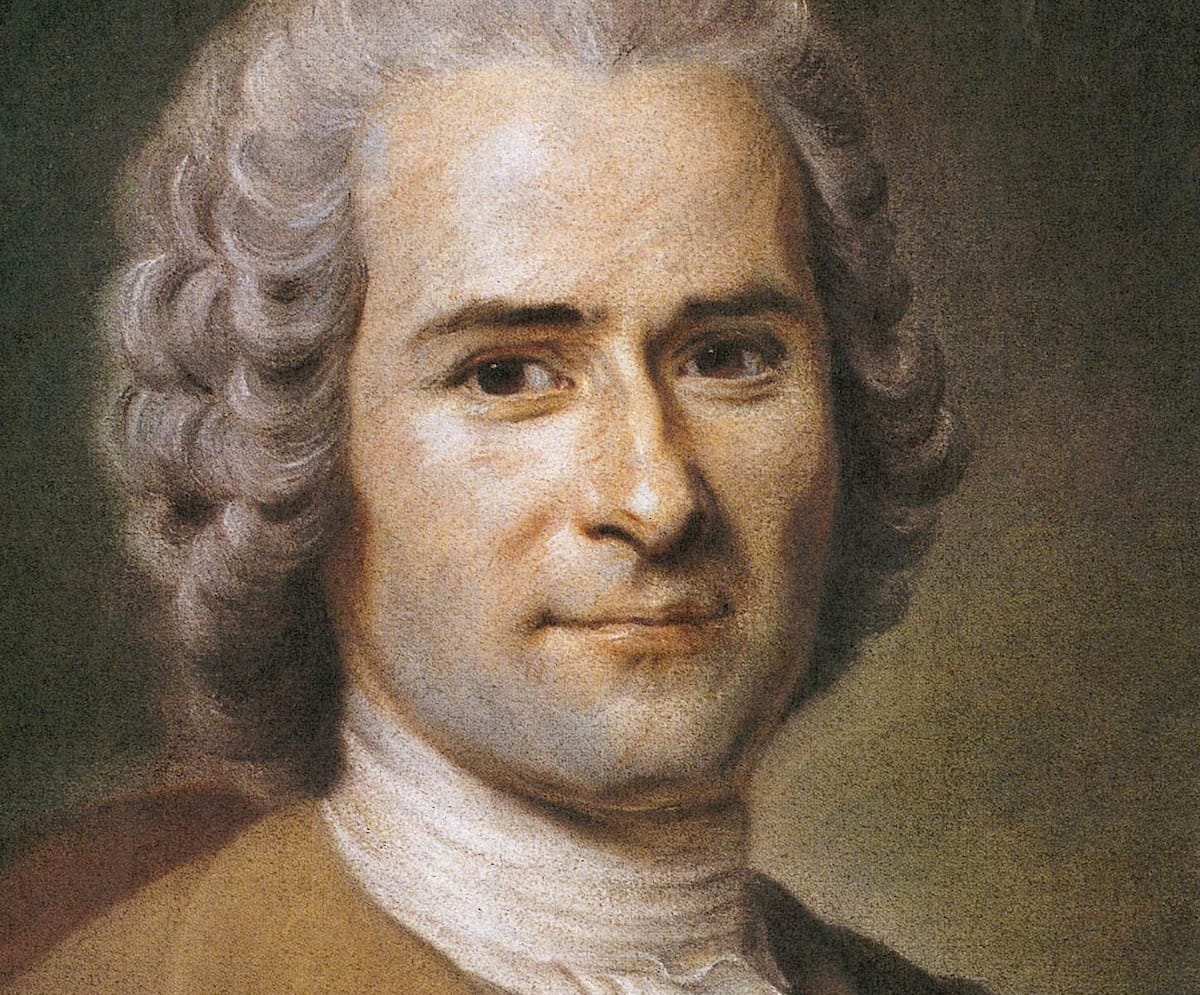

A second salient theme in Romantic political thought was provided by 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s influential work Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men in 1755. Rousseau argued that a state of nature is the ideal condition for human existence and that humanity in its natural state is intrinsically good. The evolution of legal systems, cultural institutions, and a diversified economy based on property ownership all gave rise to social inequality, conflict, and corruption, perverting people’s natural goodness into avarice and tyranny. Rousseau argued that the best system of government seeks to approximate the social arrangements of what he described as primitive peoples, like the indigenous tribes of North America and the Caribbean, whose lives most closely resembled humanity in a state of nature. This is the Romantic notion of the “noble savage.”

“Anti-colonialism” is not primarily concerned with ameliorating the destructive effects of colonialism on the people that it oppressed, but in fetishising the notion of indigenousness as a pure pre-Western state.

Rousseau’s advocacy of primitiveness as a social and political ideal bears a striking resemblance to the “anti-colonialism” of activists on the postmodern Left, who tend to be unconcerned with ameliorating the destructive effects of colonialism on the people it actually oppressed. They devote little time to improving the social and economic conditions of the native peoples of North and South America, Australia, and New Zealand. They do not seem to be interested in efforts to revive indigenous languages, which are the basis of the native cultures ravaged by colonial conquest. And they restrict their notion of colonialism exclusively to European history, while disregarding the widespread colonialist ventures of non-European empires. As a result, they have nothing to say about the suppression of Berber languages and culture in North Africa by centuries of forced Arabisation, or the oppression of indigenous Greek, Armenian, and Kurdish residents of Turkey, and the oppression of Kurds and Christians in Iraq, Syria, and Iran.

Instead, Western anti-colonialists fetishise the notion of indigenousness as a pure pre-Western state, and they press Western citizens and institutions to look at their own histories in a spirit of humility, shame, and contrition. Today, a good part of Western “decolonisation” activism is preoccupied with purging educational curricula of dead white men, changing pronouns to accommodate non-binary gender groups, and the rote recitation of tribal land-acknowledgement statements at the opening of institutional events. Since 7 October 2023, anti-colonial activists have also increased their support for the Islamist campaign to destroy Israel, in the absurd belief that jihad is just a pious kind of anti-colonial revolution.

Similarly, a strong current in the environmentalist component of the postmodern Left emphasises anti-urban rewilding and a return to nature as a response to climate change, rather than the use of advanced technology, like nuclear-fusion reactors and other clean-energy sources. The spectre of environmentalist campaigner Greta Thunberg, wrapped in a keffiyeh aboard a virtue cruise to Gaza, succinctly captures the performance politics rampant on this part of the Left. The Romantic political primitivism that Rousseau articulated in the middle of the 18th century has, in the 21st-century anti-colonial Left, blossomed into a thoroughgoing assault on Western liberal institutions and culture.

III. Old Left, New Left

The origins of the neo-Romantic revolt can be traced back to the rise of the New Left amid the cultural and political turmoil of the 1960s. The old Left—in both its revolutionary Marxist and social-democratic reformist variants—was firmly rooted in the values of the Enlightenment. It was concerned with social and economic class rather than cultural, ethnic, or gender identity; it understood the labour movement to be the primary instrument of social progress; and it sought to achieve an egalitarian society that embodied universal values of democracy and equitability. As an inheritor of the Enlightenment, Marx was careful to describe his brand of socialism as scientific to distinguish it from the utopian socialism of romantic agrarian reformers and communalists. He regarded class dialectics as the main vehicle for social change, and he posited universal historical laws according to which he believed these dialectics operate. He was not particularly interested in colonialism, and he had no sympathy for traditional non-Western societies, which he described as unenlightened and repressive.

By the 1960s, however, welfare capitalism had so successfully realised the aspirations of the Western working class that it was no longer a viable agent of revolutionary change. Contrary to Marx’s expectation, communist revolutions had occurred in the economically underdeveloped agrarian economies of Russia and China but not in the industrialised West. These revolutions had produced murderously oppressive regimes in which Marxist ideology had become fossilised dogma rather than an inspiring program for radical change. In response, the New Left replaced the working class with Third World anti-colonial nationalism as the engine of revolution. Because the nationalist organisations that waged these struggles identified as secular and paid lip-service to socialism of some variety, this ideological dislocation could be absorbed without giving up a recognisably Marxist outlook.

Unfortunately, when these national liberation movements came to power in the Middle East and Africa, most of them quickly became corrupt and repressive regimes that failed to deliver either democracy or prosperity. Shi’ite and Sunni Islamists became the new revolutionary vanguard. They seized state power in Iran and Afghanistan, and they became the leading opposition force in many other countries. The radical Western Left initially embraced Islamist movements as a tactical necessity, because no other group was capable of mounting the sort of anti-imperialist campaign required to sustain the Left’s revolutionary stance. But over time, this tactical alliance of mutual convenience evolved into a strategic coalition.

Critical theory generated a breakdown of constraints on approved moral commitments and the disappearance of the notion of scientific objectivity.

An important catalyst for this evolution was the rise of critical theory. Initially designed as a critique of bourgeois capitalist-class influence on social and cultural institutions (Gramsci, Adorno, Marcuse), it was later combined with French deconstructionist approaches to textual interpretation (Foucault, Derrida). This generated a breakdown of constraints on approved moral commitments and the disappearance of the notion of scientific objectivity. Categories of race, ethnicity, and gender now became the primary reference points in the identification of oppressive agents of control, and Western culture—denigrated as male, white, and colonialist—became the main target of opposition. In this way, the postmodern Left emptied the traditional Left of any remaining class-based politics and a commitment to Western Enlightenment values. The Left became a shell into which the neo-Romantic elixir of cultural/moral relativism and anti-colonial primitivism were poured. This toxic mix facilitated the bizarre situation in which jihadi movements have been able to colonise what now passes for the radical Left as a vehicle for its own reactionary agenda.

The postmodern Left doesn’t appear to realise that the Islamist agenda is profoundly incompatible with their own ostensibly “inclusive” libertarian cultural and gender aspirations. Nor do they seem to know what happens when leftwing revolutionary groups try to hitch their cause to reactionary movements—following the 1979 revolution in Iran, the Islamists immediately turned on the communist Tudeh Party and imprisoned or liquidated its membership and support base. This has not dampened the enthusiasm with which the postmodern Left still embraces the Iranian regime and its Islamist clients in Gaza and Lebanon. Apparently, the Left’s neo-Romantic primitivist commitments place the Islamists in the sacred class of noble savage, which exempts them from responsibility for their actions. It will be interesting to see how the Left responds when they discover that Islamists do not return the favour of granting diplomatic immunity to heterodox practices, particularly in matters of gender and lifestyle.

IV. The Antisemitic Threat

Antisemitism is an increasingly prominent element of the three dominant currents of contemporary extremism. For the New Right, suspicion or hatred of Jews is part of its broader nativist xenophobia, though until recently, concern about Jewish influence was subordinated to concern about immigration and Islam. For a while, many Western far-right organisations maintained a strange kind of pro-Israel antisemitism, which allowed bigoted views about Western Jews to coexist with support for Israel as a bulwark against Islamic influence. Numerous right-wing European nationalists and many Trump supporters display this odd combination of views. Since the Hamas terrorist attack on 7 October 2023 and Israel’s devastating military response, at least part of the New Right has converged on the extreme anti-Israel views of the Left-Islamist alliance. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the isolationist wing of the MAGA coalition, as represented by Tucker Carlson and Marjorie Taylor Greene, who are the natural heirs to Pat Buchanan’s paleoconservative legacy.

The postmodern Left insists that it is “only” anti-Zionist and that it bears no animus towards Jews as such, but this distinction is, for the most part, simply an exercise in sophistry and racist coding. It certainly has not inhibited pro-Hamas activists in Western cities and on university campuses from attacking Jews and Jewish institutions, without regard to the nature of their connection, if any, to Israel. Nor has it constrained an expanding campaign to exclude Jews not explicitly identified with anti-Israel positions from public spaces and cultural environments. For this part of the Left, Jews are custodians of white privilege, and the impresarios of settler-state colonialism. They are, by default, instruments of Israel’s power and therefore presumed guilty of its crimes by association unless demonstrated otherwise.

Islamists have targeted Jews since the inception of their movement at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In marked contrast to traditional Islamic thinkers, Islamists have developed an antisemitic theology that describes Jews as uniquely perfidious adversaries of Islam responsible for the collapse of the Ottoman Caliphate and the entry of Western imperialism into Islamic lands. Islamists regard Zionism and Israel as part of this larger conspiracy. The founding theorists of Islamism—including Muhammad Rashid Rida, Hassan al-Banna, Haj Amin al-Husseini, and Sayyed Qutb—believed the Jews to be the primary agents of Western corruption in the Middle East and in the world at large. This conspiratorial view was, in large part, imported directly from European far-right ethnonationalism and traditional Christian antisemitism, combining racial and religious anti-Jewish themes.

It is important to recognise that antisemitism is now ingrained in and integral to all three forms of modern political extremism. It is not an opportunistic prejudice adopted for short term political gain, it is expressed in eschatological terms—the Jews are an illicit collectivity obstructing the respective redemptive projects that these groups are pursuing. For the leading edge of the Left–Islamist alliance, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is not just an ugly regional dispute between rival national groups, it’s a cosmic struggle between the forces of light and darkness. It is not sufficient to object to Israel’s policies and actions; destruction of the country is a moral imperative, along with the slaughter or the expulsion of its Jewish population, which constitutes close to half of world Jewry. Only then will the world be properly cleansed and ripe for redemption. These attitudes are now seeping into expanding chunks of the New Right.

In my book The New Antisemitism: The Resurgence of an Ancient Hatred, I argue that the three modes of contemporary extremism described here are reactions to the disruption that rapid economic globalisation and technological development have caused over the past four decades. These processes have generated sharp intra-country income inequality and large-scale social displacement. This is the sort of instability that offers fertile ground for the political chaos now surging in many countries. It has shattered the postwar order and undermined the foundations of liberal democracy in the West. A surge in antisemitism has been a telling symptom of such crises in the past, as it is now.

While these three movements of the neo-Romantic revolt rampage through the streets and campuses of the West, the guardians of liberal institutions are either standing aside or engaged in craven appeasement for fear of endangering their own political and financial interests. The mainstream parties of the moderate Left, Right, and centre have shown themselves to be entirely incapable of addressing the underlying social and economic crisis that is driving their constituents to support one of the extremist options. Most people sense that the situation is not normal, but they are not clear about how far we have travelled down the road to dysfunction and collapse.

The Jews of the Western diaspora are acutely aware that they are on the front line of the current crisis, caught in the crossfire between different extremist groups, but they do not appear to appreciate the gathering danger. A small minority have chosen to join their adversaries, either on the far-left or on the far-right, hoping for protection and acceptance among their enemies. The historical precedents for this sort of collaboration indicate that it will end in disaster. The majority of Jews, meanwhile, continue to invoke the strategies of education, explanation, and public advocacy, which are of little use in an environment this poisonous and hostile.

Expressing shock at each new instance of anti-Jewish violence is not a serious strategy for dealing with the rising tide of racism. Appealing to the authorities to intervene to stop the attacks is also pointless when they are neither willing nor able to offer more than ceremonial assurances of their “zero tolerance for racial or religious hatred of any kind.” These assurances are as vapid as they are patronising. An entirely new approach is needed. It is not entirely clear what that is, but a very different sort of discussion is required and it has yet to begin.

The first Romantic revolt roiled Europe throughout the 19th century, until a bloody sequence of revolutions and catastrophic wars brought down the old order in the first half of the 20th century. The economic and social crisis that has generated the new Romantic revolt has collapsed the postwar era, and it has brought us to a state of widespread chaos. Fortunately, history does not generally repeat itself, although it frequently throws up points of similarity. The current generation has either joined the rampaging extremists, or it has remained a shell-shocked spectator, paralysed by confusion. We must hope that the next generation will be less obtuse.