Art and Culture

The Sensitivity Era

Amid literary subcultures, competition has always been fierce and unrelenting and has become even more so in our age of elite overproduction. On social media, these embittered rivalries play out in public amid a chorus of backbiting worthy of Chekhov.

A review of That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing by Adam Szetela; 288 pages; MIT Press (forthcoming August 2025) and The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech by William Deresiewicz; 368 pages; Holt Paperbacks (February 2022).

Seventy years ago, in 1955, Olympia Press published Lolita, the Russian émigré novelist Vladimir Nabokov’s scandalous masterpiece. Olympia was a small Paris-based publisher, which specialised in erotica but also brought out avant-garde literature such as Samuel Beckett’s trilogy of novels, Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable, and William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. Nabokov initially had trouble finding an American publisher for his book in the cautious and conservative 1950s when many American publishers were under the pall of McCarthyism. But the industry also featured courageous, progressively minded editors like Walter Minton, president of G. P. Putnam’s Sons, which issued the first US edition of Lolita in 1958. Minton’s bet paid off. Lolita sold 100,000 copies in just three weeks; moreover, unlike James Joyce’s Ulysses and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, it was never officially banned in the United States.

Times have changed. In a meticulously researched new book on the ills of contemporary literary culture, Adam Szetela cites editor Dan Franklin of prominent publisher Jonathan Cape, who admits that he would not risk publishing Nabokov’s masterpiece today. “Regrettably,” Szetela writes, “a novel ranked by Time as one of the hundred best English-language novels published since 1923” would likely be destined for the slush pile under the censorious new regime that prevails in publishing.

In what Szetela calls “the Sensitivity Era,” fictional narratives and characters alike must demonstrate the appropriate virtue quotient—with points awarded for marginalised identities. In this safety-obsessed milieu, Lolita’s protagonist Humbert Humbert, a white European aesthete and a confessed paedophile, triggers every moral panic alarm imaginable. In this context, even minority or underprivileged fictional characters are under scrutiny, reviewed by sensitivity readers to ensure authenticity and prevent offence. Some books receive the attentions of small armies of these “experts,” each with a particular niche focus. One publisher Szetela mentions

has a coalition of readers who consult authors on issues as different as African American culture, fatness, familial homophobia, conception via sperm donation, rural queer experience, Chinese American culture, furry fandom, interracial relationships, Contemporary Jewish culture, mental abuse by a parent, traveling while black, Hinduism, ableist physician experiences, Iroquois culture, men who survive rape, LGBTQIA2+ representation, and witchcraft.

Some agents and publishers require authors to hire their own sensitivity readers before a manuscript is reviewed. As Szetela remarks, this requirement squeezes aspiring writers financially while perpetuating the bizarre notion that “there are ‘authentic’ and ‘inauthentic’ ways” to portray a character from a minority background or to be part of a minority oneself. In short, “the Sensitivity era treats identity as the precondition for well-written literature”: a view so plainly at odds with truth that it is hard to imagine how it ever took hold.

Szetela has a theory about this: fights over identity are usually centred on interpersonal and intergroup status. This explains their prevalence in literary subcultures, where recognition is scarce and often fleeting, and competition is fierce and unrelenting. Szetela suggests that many online cancellations are manifestations of what the philosopher George Santayana called the “passions grafted on wounded pride.” The most ardent cancellers are often people who experience perceived slights to their status as forms of narcissistic injury that call for retribution through mob justice. Szetela cites the example of the self-styled “sensitivity expert” Lorena Germán, who encouraged an online pile-on after writer Jessica Cluess criticised one of Germán’s social media posts in support of the #DisruptTexts movement Germán cofounded, a movement to ban supposedly outdated classics that might be propagating bad values. The social media mob accused Cluess of the usual sins of “harm,” “violence,” and “racism” and, as is typical, the author ended up issuing a grovelling apology in an effort to regain her standing with her peers.

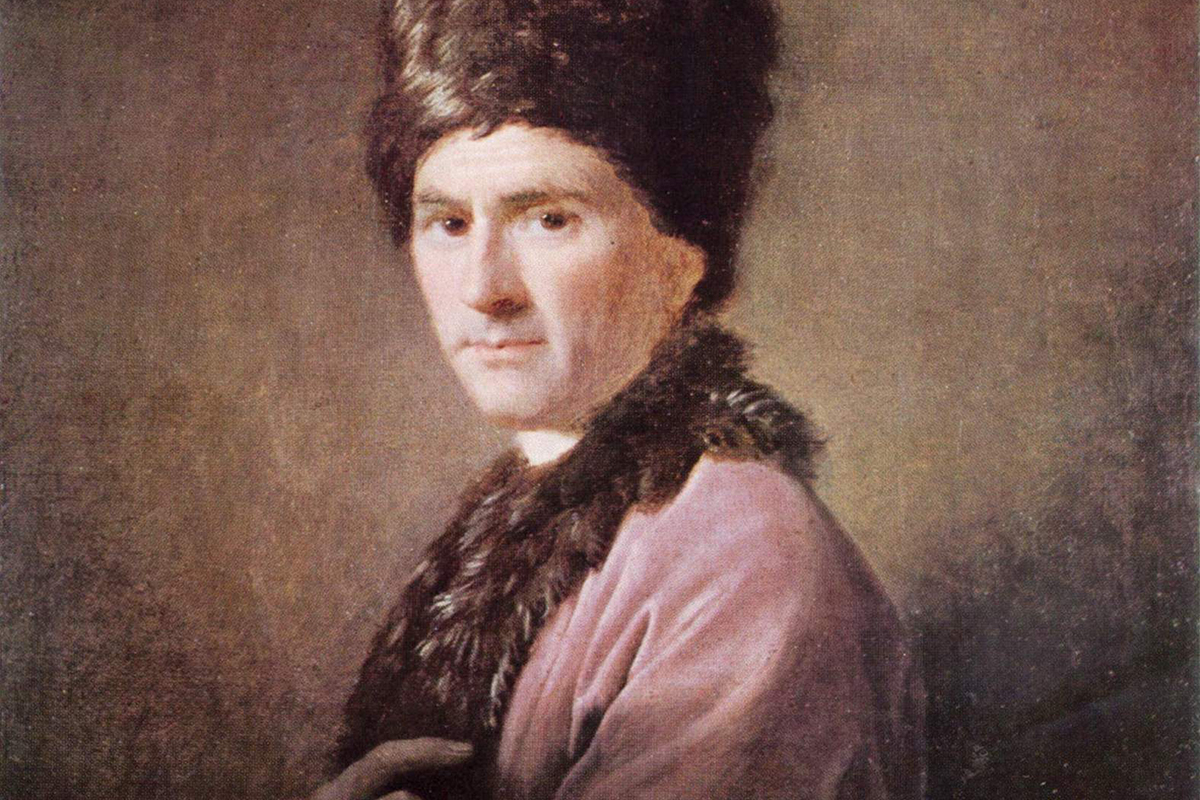

According to the Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writing in 1755 amid an earlier era of moralistic sensitivity, one basic condition of social existence is believing that we are entitled to the consideration of others: “As soon as men had begun to appreciate one another and the idea of consideration had taken shape in their mind, everyone claimed a right to it, and one could no longer deprive anyone of it with impunity.” The same right often extended to collective affiliations; an insult to one’s kin group or nation becomes a personal affront, a form of disrespect that requires repayment in kind. According to Rousseau, we may respond to perceived offence by depriving the offender of their right to esteem in the eyes of others—in other words, through public shaming. (This was an enlightened improvement on the previous means of obtaining retribution: through duelling.)

Shame is a highly contagious emotion: perpetrators of shaming crusades often become victims in their turn. According to Szetela, shame spreads through online literary communities with the virulence of a parasite attacking an ant colony. Even prominent publishers and reviewers often have to carefully hedge their bets to avoid guilt by association. Szetela notes how the literary magazine Kirkus Reviews, for example, has often retracted or rewritten book reviews under pressure from social media users. Fear of the online tantrums of aggrieved actors incentivises performative repudiation. As Szetela writes: “No one wants to be associated with a writer who was accused of insensitivities.” Agents and publishers shun authors “who have been, or who may become, targets of the internet mob.” Most actors in the online shame economy seem naively convinced of their moral righteousness—until they too are cancelled.

More actively devious players undertake self-promoting campaigns of moral entrepreneurship aimed at raising their status—cue Ibram X. Kendi, whom Szetela accuses of having aggressively monetised “antiracism” as a personal brand. To be fair, Kendi has notable scholarly credentials and a compelling backstory and is perhaps less likely to be merely a moral entrepreneur than some of Szetela’s other examples, such as professional sensitivity reader Kosoko Jackson and New York Times columnist Roxane Gay. Moral entrepreneurship manipulates the social capital of communities that have developed dense cooperative networks based on shared norms. As the ultimate in specious virtue signalling, moral entrepreneurship bears the same relation to morality that televangelism does to piety.

Creative fields like literature are often very unfair. First there is the fact that talent isn’t apportioned equally. But worse, talent is seldom enough to guarantee success in the arts. As William Deresiewicz points out in The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech, the arts have long “skewed rich,” but they have grown ever more elite. Many young artists and writers rely on family wealth to boost their careers since few can afford the years of costly higher education, unpaid internships, and poorly compensated entry-level positions increasingly required as the entry ticket to many creative fields. As former Harper’s Magazine editor Gemma Sieff remarks, the culture industry “is a de facto class system.”

Yet the disquieting problem of class inequality in the arts is often ignored amid moral panics over race and gender. Perhaps this misplaced focus is even intentional. A dirty secret about diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in elite spaces such as universities and arts organisations is that DEI policies often benefit the already privileged. In this regard too, Szetela offers a useful corrective. Like Deresiewicz, he focuses on the experiences of working artists who are neither celebrities nor scions of wealth. Both authors chronicle the disappearance of economic opportunities for members of this group, along with the rise of the internet’s flattened distribution model. These trends align with the rise of the university as the dominant patron of the creative professions, especially in the United States. As one of Deresiewicz’s subjects, a graduate of the Parsons School of Design, observes prestigious art schools attract “a huge percentage of international students who are paying full tuition,” while their enrolments of domestic students from lower-income backgrounds have been declining—a trend that is increasingly visible in other fields too.

Like almost every other contemporary institution, the arts are now mediated primarily by the internet. Like their social sorting mechanisms, the taste-making and marketing dynamics of online spaces are notoriously flattening. Online discourse reconstitutes individual creators as nodes in densely clustered networks, in which the secret to success lies in high-visibility antics and consistent branding. Hashtag social-justice campaigns offer powerful marketing tools that emerging artists and writers courting progressive audiences ignore at their peril. Adding the right emoji or hashtag to one’s social media profiles signals solidarity and virtue on the cheap.

Rousseau’s great insight was that the first step toward social inequality emerges with the enforced recognition of natural differences that a complex and interdependent form of social life compels:

Everyone began to look at everyone else and to wish to be looked at himself, and public esteem acquired a price. The one who sang or danced the best; the handsomest, the strongest, the most skilful or the most eloquent came to be the most highly regarded, and this was the first step at once toward inequality and vice: from these first preferences rose vanity and contempt on the one hand, shame and envy on the other, and the fermentation caused by these new leavens eventually produced compounds fatal to happiness and innocence.

Talent is rare, but the desire for esteem is universal. Social media amplifies this attentional feedback loop, spurring ever more hyper-competitive and socially divisive behaviour.

The arts have long been an especially disputatious arena. The struggle for recognition has grown fiercer under current conditions of attentional scarcity and elite overproduction. As Deresiewicz writes, “everybody seems to feel entitled to the honor” of proclaiming themselves artists “as if by a kind of human right,” noting the startling fact that “from 1991 to 2006, the number of bachelor’s degrees conferred in visual and performing arts increased by 97 percent” in the US, a period that coincides with the rise of the internet. The conditions of chronic financial stress under which most artists live also drive polarisation and populist anger. As success and failure start to seem increasingly arbitrary and zero sum, rivalries play out in public amid a chorus of backbiting and grudges worthy of Chekhov. Cancel culture reflects our social ecology—or as Deresiewicz puts it, “what our brutally unequal economy is forcing young people to do and to be.” Therefore some compassion is called for, alongside Szetela’s well-earned satire. The depressing vista of literature and the arts in the age of the internet confirms Rousseau’s timeless insight: the major source of human unhappiness in society is our need for the approval of others and our fear of their rejection. These status hunger games grow ever more ferocious the less status there is to go around.