Politics

Trump and the Necessity of Democratic Struggle

Liberal pluralism remains the best way to secure as much freedom as possible for a nation with 340 million diverse inhabitants, and this point should become clearer as clashing illiberal forces compete to impose their own versions of law and morality on everyone else.

I.

In a 1784 essay, Immanuel Kant makes a case for the merits of what he called humanity’s “asocial qualities.” He writes: “Nature should … be thanked for fostering social incompatibility, enviously competitive vanity, and insatiable desires for possession or even power. Without these desires, all man’s excellent natural capacities would never be roused to develop.” Other philosophers have made similar observations. Friedrich Nietzsche, in his attempt to overturn traditional notions of morality, called upon human beings to actively pursue power and strength: “What is good?” he asks in The Antichrist. “Everything that heightens the feeling of power in man, the will to power, power itself.” Nietzsche also calls upon his readers to seek “Not contentedness but more power; not peace but war; not virtue but fitness.” In The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli argues that leaders should focus on the acquisition and maintenance of power—even if they must abandon traditional moral constraints to do so.

Healthy societies provide the institutional framework necessary for people to exercise their “asocial qualities” without violating the rights or freedoms of anyone else. Unlike Nietzsche or Machiavelli, Kant cautioned against discarding moral constraints in the pursuit of power. Kant’s categorical imperative holds that certain moral requirements are universally applicable to all people at all times. Kant demanded that rational agents treat each other as ends in themselves, rather than means to other ends. While Kant believed that rulers should be bound by the categorical imperative just like anyone else, Machiavelli argued that they should be free to transgress certain moral rules in order to retain power. Nietzsche was intensely critical of Kantian morality, arguing that it was an echo of Christian “slave morality” that impedes the progress toward human greatness and the emergence of the Übermensch.

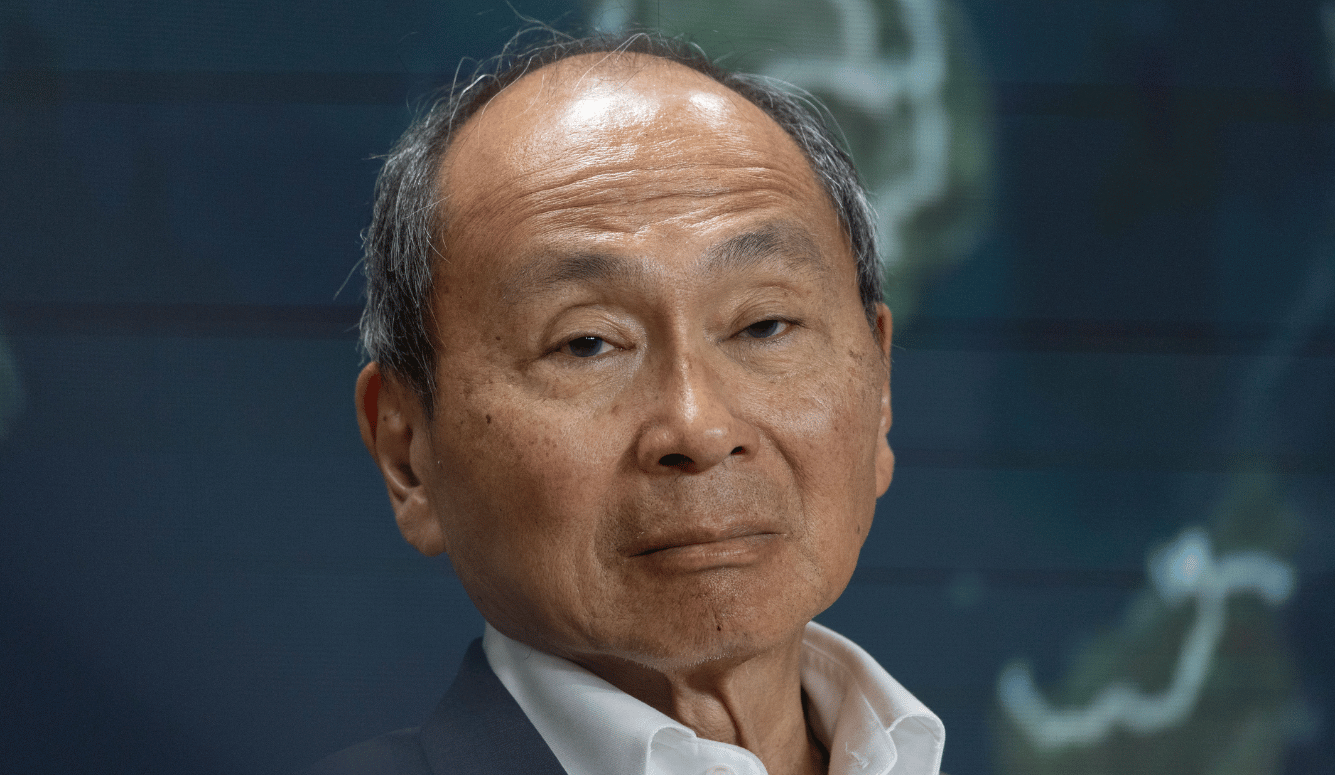

However, Kant shared Nietzsche’s conviction that a life of struggle is essential for human development. “Man wishes to live comfortably and pleasantly,” Kant wrote, “but nature intends that he should abandon idleness and inactive self-sufficiency and plunge instead into labour and hardships, so that he may by his own adroitness find means of liberating himself from them in turn.” While people want comfort and security, they also want struggle and discord. This is an overlooked theme of Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man, which emphasises the “struggle for recognition” as a central driver of history. Although liberal democracy provides universal recognition to citizens—which is why Fukuyama argues that it is the most sustainable form of government—he has long suspected that institutionalised equality and pluralism would fail to satisfy the need for struggle among many people.

“Is there not a side of the human personality,” Fukuyama asks, “that deliberately seeks out struggle, danger, risk, and daring, and will this side not remain unfulfilled by the ‘peace and prosperity’ of contemporary liberal democracy?” Recall Kant’s acknowledgment of our “enviously competitive vanity” and “insatiable desires for possession or even power.” Fukuyama contrasts two different types of recognition that people demand, based on the Greek concept of “thymos,” which is roughly translated as “spiritedness” and concerned with a person’s self-conception as a being with moral worth. Fukuyama distinguishes between isothymia and megalothymia—the former refers to the desire to be treated equally, while the latter refers to a desire to be recognised as superior.

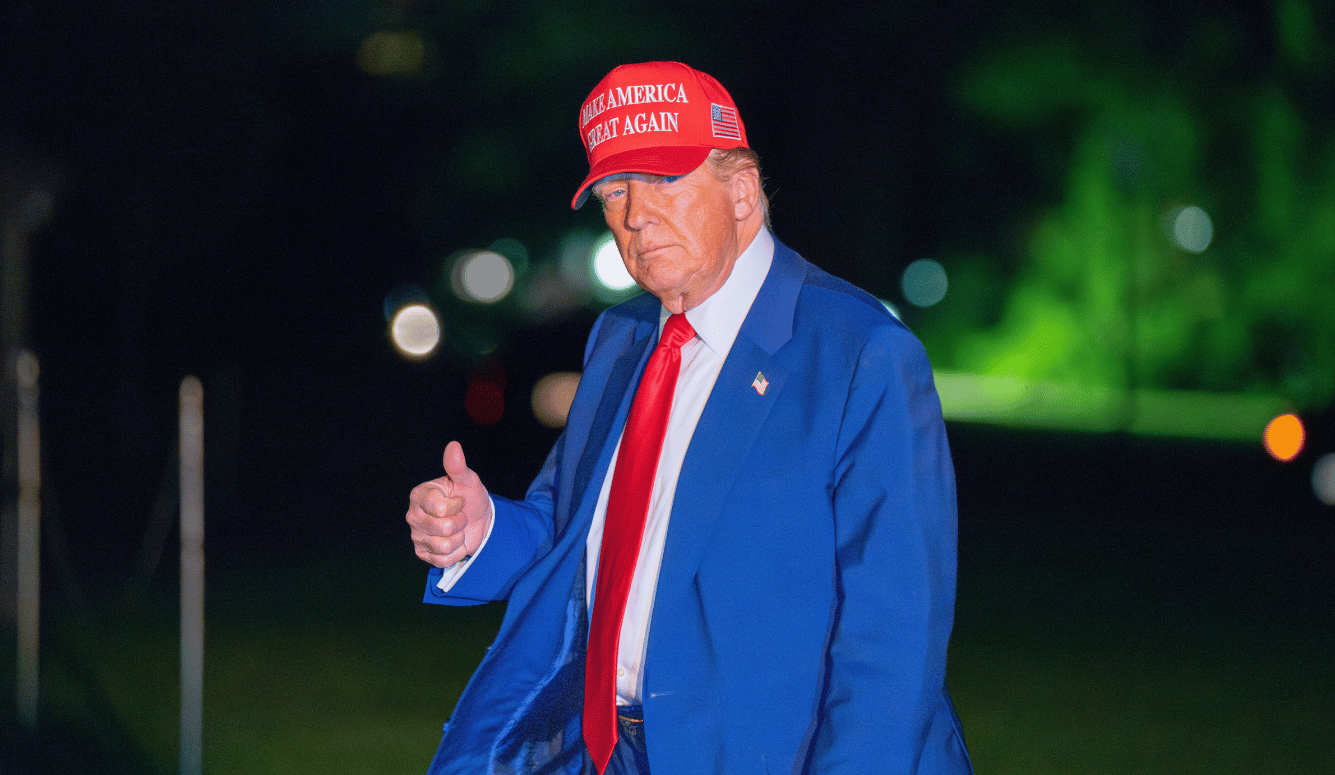

Some forms of recognition-driven politics operate squarely within the isothymotic parameters of liberal democracy, as they involve groups demanding equal rights and dignity under the law. The Civil Rights movement is the best example of this form of politics, as leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. demanded universal recognition for all—not power over others. But the pursuit of recognition can also be megalothymotic—when one group demands special privileges on the basis of race, religion, or some other exclusive tribal characteristic. This is a central feature of Donald Trump’s MAGA movement, which explicitly calls for the elevation of some citizens and the marginalisation of others. A clear example is Trump’s January executive order which attempted to overturn the clause of the Fourteenth Amendment which grants citizenship to anyone born on American soil. While these Americans are legal citizens of the United States under the Constitution, the Trump administration does not regard them as equal to other citizens.

In 1992, Fukuyama described Trump as a person driven by megalothymotic desire who was able to fulfil that desire in a relatively benign way—by becoming a celebrity businessman. But Fukuyama explained the risk of megalothymia in politics. “It is clear that megalothymia is a highly problematic passion for political life,” he writes, “for if recognition of one’s superiority by another person is satisfying, it stands to reason that recognition by all people will be more satisfying still.” This is why Fukuyama observes that megalothymia is what fuels the “tyrannical ambition of a Caesar or a Stalin.” The only way to check these megalothymotic ambitions in politics is through the rule of law and strong democratic institutions—such as the separation of powers in the United States government. The American Founders understood the importance of checking tyrannical ambition. As James Madison explains in Federalist No. 51:

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

This is why Madison argues that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition” in the form of separate but co-equal branches of government that would submit to the legitimate authority of the others while jealously guarding their own power. But as we have seen over the past six months, this formula is far from foolproof. Congress has repeatedly surrendered its power to Trump since his second term began. It has allowed him to impose economically destructive and chaotic tariffs unilaterally, under the ridiculous rationale that trade deficits represent a national emergency. It refused to stop him as he destroyed entire agencies created by Congress, such as USAID. Just last week, Congress allowed Trump to cancel US$9 billion in spending it had already approved. Many Republicans had deep concerns about Trump’s signature piece of legislation—a deficit-exploding tax bill that will throw millions of people off Medicaid in exchange for tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the wealthiest Americans. But they went along with it, despite its unpopularity among voters.

It’s no mystery why members of Congress have surrendered to Trump—he is a vindictive authoritarian who will try to destroy their political careers if they defy him. This is what Kentucky Rep. Thomas Massie recently discovered when he opposed Trump’s decision to join Israel’s military campaign in Iran. Trump immediately responded by announcing that he would support a primary challenger to Massie and declaring that “MAGA doesn’t want him.” Trump rules his party by fear, and he has built a cult of personality that makes it extremely difficult for members of Congress to resist his demands.

While the prostration before Trump makes sense as a political defence-mechanism among Republicans, the deeper question is how he has been able to maintain the support of a significant share of the electorate. Without that support, members of Congress could resist his efforts to usurp their power, subvert the rule of law, and break the United States’ fundamental democratic norms and institutions. But Trump has remained the dominant force in American politics for a decade, and while his popularity has wavered since the start of his second term, millions of Americans still support him. It’s important to understand why that is.

II.

In a 1940 review of Mein Kampf, George Orwell observed that Adolf Hitler was able to build a following and secure political power because he “grasped the falsity of the hedonistic attitude to life.” Orwell argues that “human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades.” He continued: “Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people ‘I offer you a good time,’ Hitler has said to them ‘I offer you struggle, danger and death,’ and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet.”

Hitler didn’t promise his followers that he would give them lives of leisure—he promised to avenge what many Germans viewed as an unjust settlement after World War I. The Treaty of Versailles imposed severe economic sanctions on Germany, forced the country to pay massive war reparations, led to a significant loss of territory, and placed strict limits on the German military. The putative measures taken against Germany coupled with the country’s massive war debt had devastating economic consequences, particularly the hyperinflation of the early 1920s. In this context, a myth that blamed Jews for the country’s defeat and impoverishment rapidly spread and created the conditions for the rise of the Nazis.

On 15 March 1929, Hitler delivered a speech in Munich about the Nazi program for rearmament: “If men wish to live,” he declared, “then they are forced to kill others.” He continued: “We admit freely and openly that if our movement is victorious, we will be concerned day and night with the question of how to produce the armed forces, which are forbidden us by the peace treaty [the Treaty of Versailles].” He claimed that “Our rights will be protected only when the German Reich is again supported by the point of the German dagger.” Hitler welcomed the widespread economic misery and festering resentment at Germany’s defeat in World War I because he understood that these were powerful engines of political mobilisation. He took it for granted that Germans would prefer a ruler who promised a struggle to restore their national glory over one who merely promised an improvement in their material conditions.

Trump is no Hitler, but his political appeal has always revolved around a similar ability to cultivate and exploit grievances and social division. His central message is that his political opponents are trying to destroy the country and they must be ferociously resisted. When Trump was out of power, he declared that the economy was collapsing, that the United States had become a “banana republic,” and that the country was in a state of terminal decline. This grim and embittering political message has been successful even though the United States doesn’t confront anything like the challenges that gave oxygen to other authoritarian movements. The US economy is strong, unemployment is low, inflation was tamed without pushing the country into recession, and Americans have not just experienced a crippling defeat in a devastating World War. Common explanations for Trump’s rise include the United States’ post-11 September wars (particularly Iraq), the 2008 global financial crisis, and a general sense of anti-elite hostility over these failures. But Americans’ living standards are uniquely high by any historical measure, they have robust rights and freedoms, and the United States is the most powerful and secure country on earth.

As Fukuyama noted in a recent conversation, there “seems to be this disjunction between populist anger and actual outcomes.” When I asked him to expand on this comment in an interview for Quillette, he said: “What I can’t understand is why there are so many people in the United States today that are asserting things like: ‘well, things have never been worse’ or ‘our society is on the brink of collapse.’” He noted that many of the complaints on the populist Right amount to little more than cultural anxiety—the idea that traditional values and faiths are being undermined in modern liberal society—but these complaints have been blown into “existential fears that our way of life is just going to completely collapse.”

In The End of History, Fukuyama makes a prescient observation: “Experience suggests that if men cannot struggle on behalf of a just cause because that just cause was victorious in an earlier generation, then they will struggle against the just cause.” The United States has entered an era in which the just cause of liberal democracy is no longer enough to inspire many Americans, who are more committed to various cultural and political tribes than they are to the universal democratic principles upon which the country was founded. This has always been one of the central problems with liberalism—because it offers the freedom to believe whatever one wants as long as those beliefs don’t trespass on the rights of others, citizens of liberal democracies fragment into tribes based on shared affinities and values that go deeper than national solidarity. These tribes often become increasingly insular and hostile toward outsiders, and they develop megalothymotic tendencies—such as American Christians who believe their faith should hold a special position in the public square. Such assertions have become common among influential “postliberals” like Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule (the former has been cited approvingly by Vice President J.D. Vance).

Trump’s political movement is purely megalothymotic. He has never even pretended to be a president for all Americans—he describes his political opponents as “evil,” “scum,” and “vermin.” During the 2024 election, he repeatedly said the “enemy within” is a greater threat to the United States than Russia, China, or any other geopolitical foe. He said immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country.” He promised to “totally obliterate the deep state,” which has turned out to mean purging any federal employee who doesn’t submit to MAGA orthodoxy and destroying entire agencies that don’t align with Trump’s political goals.

While debates over Trump’s attack on American democracy tend to focus on the 6 January assault on the US Capitol, the greater scandal was his broader, sustained campaign to overturn the results of the election. This campaign was accompanied by a relentless effort to undermine faith in American democracy, which Trump repeatedly decried as “rigged,” a “scam,” and so on. At a time when confidence in American democratic institutions is already dangerously low, Trump has done everything in his power to diminish that confidence further. Even in the world’s most powerful constitutional republic, disenchantment with the political status quo can empower a megalothymotic ruler to systematically challenge and dismantle democratic norms and institutions. Fukuyama recently cited a 1941 Leo Strauss speech on German nihilism as a prefiguration for some of the trends on the American Right today. Strauss said: “Let me tentatively define nihilism as the desire to destroy the present world and its potentialities, a desire not accompanied by any clear conception of what one wants to put in its place.”

Trump has corroded essential democratic norms like the peaceful transfer of power, sapped the authority of Congress, and attacked the independent judiciary. He has brazenly used the power of the presidency to enrich himself and his family. He has no positive vision for governance beyond self-aggrandisement. As the strength of liberal democracy in the United States continues to erode, the MAGA movement offers nothing in its place. But Trump doesn’t need a positive vision for the country. He can always exploit fear, contempt, and the restless desire for struggle to pit his supporters against the “enemy within.”

III.

Kant argued that “antagonism within society” is the “means which nature employs to bring about the development of innate capacities.” He was thinking of productive social and civic discord—not the scapegoating and oppression of certain groups or the tribalism that feeds authoritarianism. Kant recognised that the pursuit of power could be an engine of progress, but he believed this pursuit should be checked by strong moral constraints and a “law-governed social order.” This is because the asocial qualities that “encourage man towards new exertions of his powers” also “cause so many evils.”

That these evils continue to exist in a mature democracy like the contemporary United States would come as no surprise to philosophers like Kant, Nietzsche, and Machiavelli, nor would this fact shock American Founders like Madison. Liberal democracy will always be vulnerable to exploitation by demagogues like Trump, who have an instinctive understanding of how to manipulate public opinion in ways that increase their power. In his book The Open Society and Its Enemies, Karl Popper does not assume the “intrinsic goodness or righteousness of a majority rule.” Popper assumed that democratic citizens would sometimes freely choose a tyrant to rule them—a “paradox of freedom” that was first articulated by Plato. This is why Popper advanced a “theory of democratic control” primarily designed to “avoid and to resist tyranny.”

In the post-Trump era, it will be necessary to restore and strengthen the institutions of American democracy to protect them from future would-be tyrants. There must be an effort to rein in executive authority, which has been expanded by a series of Supreme Court rulings but can still be checked by Congress. To take one salient example, the president should no longer have the power to unilaterally throw the global economy into turmoil and risk an American debt crisis by imposing, removing, and reimposing massive tariffs on a whim. There is no national-security justification for Trump’s tariffs, which contradict the letter and spirit of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—the law Trump has used to justify his actions.

There must also be anti-corruption legislation on a scale that will make the post-Watergate reforms look modest by comparison. After Trump issued his meme coin, investors from around the world suddenly had a way to publicly bribe the president of the United States. Trump is listed as the “Chief Crypto Advocate” in a “gold paper” issued by World Liberty Financial, a crypto platform that generates huge amounts of money for him and his family. Trump is the most powerful regulator of an industry that now accounts for a significant proportion of his wealth. His crypto holdings create the largest vehicle for influence peddling in American history. After World Liberty received US$75 million from the crypto magnate Justin Sun, an SEC investigation of Sun was suddenly suspended.

It’s no wonder that Trump has been systematically dismantling the internal checks on corruption and abuses of power in the United States, from immediately firing seventeen inspectors general to ending enforcement of anti-corruption measures like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the Corporate Transparency Act. No future president should be allowed to profit from such egregious conflicts of interest, and anti-corruption laws should be strong enough to prevent such flagrant abuses of power.

Beyond these institutional reforms, there must be a recommitment to liberal-democratic norms and institutions within civil society. According to Kant, “continual antagonism” is inevitable in a free society, which requires a “precise specification and preservation of the limits of this freedom in order that it can co-exist with the freedom of others.” This is the basic liberal compact, and it is at risk of breaking down in the United States. Surging polarisation since the end of the Cold War has led to a breakdown in social trust, along with the forbearance and tolerance necessary for a democratic civil society to function. The central puzzle for liberals to solve in the coming decades is how to increase national solidarity around a shared commitment to principles and institutions like democracy, individual rights, and the rule of law. Liberal pluralism remains the best way to secure as much freedom as possible for a nation with 340 million diverse inhabitants, and this point should become clearer as clashing illiberal forces compete to impose their own versions of law and morality on everyone else.

In one sense, the United States’ authoritarian moment is just another example of the “continual antagonism” emphasised by Kant. Trump’s rise to power demonstrates that Americans were willing to risk the health of their democracy to dislodge a political status quo that they no longer accepted. It isn’t necessary to agree with them that this was a risk worth taking to recognise that their intense disenchantment with liberal democracy poses a grave threat that must be addressed. Trump has aggravated antagonism within American society between those who value democracy, pluralism, and the rule of law and those who do not. He has forced the American political debate back toward first principles: why is the peaceful transfer of power important? Why is corruption corrosive to good government? Why do we have a system of checks and balances? Why does the rule of law constrain the executive? Why do we have an independent judiciary? As populist authoritarians attempt to entrench their anti-democratic ideology around the world, liberals better have coherent and politically compelling answers to these questions.

The United States has faced greater threats than the slide toward populist authoritarianism—from fascism and communism in the 20th century to slavery and the Civil War in the 19th. Liberal democracy has proven capable of adapting to these monumental challenges and course-correcting when necessary. This is why it is likely that the United States’ authoritarian moment will be just that—an aberration brought about by the civic complacency that comes with centuries of democratic governance and decades of prosperity and stability. There are already signs that this complacency is being jolted. Trump’s approval rating is sagging, his main legislative achievement is deeply unpopular, and Americans are losing faith in his ability to handle the issues on which he was elected, such as immigration and the economy. Now that Americans are witnessing mass deportations and unilateral tariffs in practice—instead of as campaign slogans—they don’t like what they see.

The Trump era will be remembered as a turn away from America’s most cherished democratic principles. But it may be necessary every generation or so to confront a challenge like this, which demonstrates that democracy isn’t self-perpetuating. After Trump won his largest victory in the 2024 election, his political opponents realised that they could not return to the pre-Trump status quo. This is why many liberals have exchanged trivial fights over identity politics for ideas like an “abundance” agenda, which calls for a focus on tangible outcomes and the types of big projects (the Hoover Dam, moon landing, etc.) that now seem to be a distant memory. As Fukuyama told me: “if you actually want to get to progressive aims … you’ve got to be able to build stuff.”

Liberal democracy has a tremendous record of building stuff—especially societies that attract people from all around the world and have proven capable, over and over again, of outlasting their authoritarian rivals. This case must be made anew. The “antagonism within society” created by Trumpism is dangerous because it has weakened the guardrails of liberal democracy that we had long taken for granted. But we never should have taken those guardrails for granted in the first place. Trump has ensured that it will be a long time before complacency sets in once again in the United States. He has provided the impetus to radically reform our democratic institutions so that they are more responsive to public demands and better protected against authoritarian encroachment. And perhaps most importantly of all, he has given a decadent and comfortable society something to struggle against—and the emerging prospect of a better society to struggle toward.

“Man wishes concord,” Kant wrote, “but nature, knowing better what is good for his species, wishes discord.” The period of discord we are living through now may be painful, but it may also be the catalyst for a democratic revival. Only history will be able to tell us if our renewed sense of purpose was worth the cost.