Activism

Rethinking “Harm Reduction”

Once seen as a model of progressive drug policy, San Francisco now stands as a morbid example of how that approach has gone astray.

San Francisco has long been the unofficial “harm reduction” capital of the United States. Harm-reduction policy operates on the premise that total abstinence from drug use is often unrealistic and that it is better to “meet addicts where they are.” Ever since the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic opened in 1967 to provide medication-based addiction treatment, the City by the Bay has pioneered policies and practices designed to mitigate the potential dangers of drug use.

San Francisco made harm reduction an official public-health policy in 2000. The county suffered 103 deaths by accidental overdose that year. However, in 2023, San Francisco lost a record 810 residents to drug overdoses. This amounted to one fatal overdose for every thousand residents, making the city one of the deadliest in the country for those with substance-abuse disorder. The rise of fentanyl—a synthetic opioid—has caused overdose mortality rates to rise nationally, but San Francisco’s rates have skyrocketed.

San Francisco’s new mayor, Daniel Lurie, has begun modestly pulling back on publicly funded harm-reduction activities. “We can no longer accept the reality of two people dying a day from overdose,” Lurie said. For a city that prides itself on its radical progressivism and tolerance of drugs, the turn against harm reduction—at least, as it has been practised for the past quarter-century—reflects a momentous change in how residents think about drug policy.

Laura Guzman, the executive director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, called Laurie’s shift away from harm reduction “moronic and antithetical to what we know works.” But as the fentanyl epidemic rages, Guzman’s position is becoming increasingly difficult to defend. Even outside of California, the cities with the highest overdose mortality rates—Baltimore, Portland, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, and Denver—all embraced San Francisco’s approach to harm reduction. Clearly, “what we know works” isn’t working.

With even San Francisco souring on harm reduction, it is time to rethink the philosophy. Once seen as a model of progressive drug policy, San Francisco now stands as a morbid example of how that approach has gone astray. It is worth understanding how that happened, and how it can be fixed.

The problem in San Francisco and other progressive cities is that harm reduction has become completely divorced from recovery. What began as a campaign to keep people alive long enough to recover from addiction has devolved into a philosophy that no longer considers recovery as necessary or even desirable. The question of whether or not harm reduction is successful comes down to whether it is treated as a gateway to recovery, or as an alternative to it.

I. The Utilitarian Logic of Harm Reduction

Although the earliest harm-reduction efforts trace back to the 1960s, the philosophy only began to formalise in the mid-1980s with the sudden emergence of the lethal HIV virus, which disproportionately affected homosexual men and intravenous drug users. Because HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, can be transmitted through the bloodstream, needle-sharing practices among heroin addicts dramatically heightened the risk of infection.

The AIDS epidemic hit San Francisco especially hard, due to the city’s large gay community and disproportionately high population of drug users. Non-profits began combatting the dangers by encouraging users to sanitise used needles with bleach, and they eventually began handing out clean syringes. In 1988, a volunteer organisation known as Prevention Point began operating underground needle-exchange programs. For nearly four years, volunteers illegally handed out clean syringes—which they distributed from baby carriages—collected used needles, and offered referrals to drug-treatment services. Finally, in 1993, San Francisco became one of 33 US cities to implement an official needle-exchange program, which allowed users to swap their used syringes for new ones.

Needle exchanges were designed to reduce harm for the whole population, not just intravenous drug users. The “exchange” requirement was put in place to reduce biohazard waste. By making users turn in dirty needles, exchange programs not only made needle sharing less common, but they also helped keep used syringes from littering sidewalks.

As the philosophy of harm reduction began to take shape in response to the AIDS crisis, nobody denied there were tradeoffs. Drug overdoses were already the most common cause of accidental death in San Francisco, and the concern with harm reduction was that by making it easier for people to use hard drugs, we would be inadvertently subsidising a deadly behaviour. But AIDS made needle sharing more dangerous than heroin, which provided the simple utilitarian logic of harm reduction: we should do what we can to keep people alive long enough to recover from their addiction.

Needle exchanges were tremendously successful. By the late 1990s, rates of HIV exposure dropped by 33 percent among participants in needle-exchange programs. Although HIV prevention was the primary goal of needle exchanges, they also produced higher rates of treatment enrolments. One study found that “new users of the exchange were five times more likely to enter drug treatment than never-exchangers.” The same study also noted that, at the time, nearly every needle exchange in the country provided treatment referrals, which is no longer allowed under California law.

The success of needle-exchange programs encouraged San Francisco and other progressive cities to lean further into harm reduction, and the policies began to evolve. Needle exchanges eventually became distribution programs. By no longer requiring users to turn in used syringes, harm reductionists sought to remove one of the remaining barriers to accessing clean needles. The benefits of reduced needle sharing remained in place, but streets and sidewalks became covered in dirty syringes. Harm reduction was starting to omit non-users from its harm–benefit calculus.

In 2018, Mayor Mark Farrell hired a team of ten workers whose sole job was “the collection and disposal of more than 275,000 needles per month.” Yet even that was insufficient to keep the problem at bay. GLIDE Memorial Church—a harm-reduction organisation based in San Francisco’s Tenderloin District—tried paying US$20 for dirty needles at one point, but people gamed the system by collecting clean needles, pouring Coca-Cola on them, and turning them back in for cash. Gina McDonald, co-founder of Mothers Against Drug Addiction and Deaths, filed a public-records request for data on San Francisco’s taxpayer-funded syringe-access program and discovered that, between 2020 and 2024, the city distributed more than eighteen million needles but collected only ten million.

Today, San Francisco has taxpayer-funded programs that not only distribute needles, but also “safer smoking” harm-reduction kits that have little to no impact on the risk of contracting disease. The kits include things like pipes, tin foil, and straws, which are frequently used for smoking illicit drugs. The flimsy justification for these kits is that cracked lips can still be a source of infection, though this assumption lacks clear scientific support. In the absence of proper studies, one user raised the question with their doctor after sharing a pipe with an HIV-infected person and was told that “the blood would have to be pretty much dripping on the pipe to have a risk.”

Harm-reduction kits vary by city and organisation, but it is not uncommon for these kits to include instruction pamphlets that teach users how to consume drugs. In his memoir Crooked Smile, Jared Klickstein describes receiving “government-sanctioned advice” on how to mainline heroin through a pamphlet he was given by a needle exchange. “What the pamphlet didn’t have,” he recalls, “was any information about accessing drug treatment or detox.”

The utilitarian calculus of harm reduction also looks very different from when cities first introduced needle-exchange programs. Heroin addicts in the 20th century could carry their addiction for decades, and opioids only accounted for a relatively small percentage of fatal drug overdoses. AIDS, on the other hand, meant certain death, so the greatest risk of using heroin in the early 1990s was not overdose but the contraction of a blood-borne virus by sharing needles.

Medical advances have since ensured that AIDS is no longer a death sentence, but the days of decades-long opioid addictions are also behind us. Fentanyl is a hundred times more potent than morphine. Overdose is now the greatest danger associated with drug use, and many harm-reduction efforts have neglected to adapt to this new reality. But the philosophy survives in San Francisco as an article of faith among ideologically motivated activists. It’s not that harm reduction transformed from a good idea into a bad one, it’s that we stopped considering whether or not the policies and practices operating under its mantle actually produce the promised outcomes.

This does not mean that needle exchanges—as they originally operated—should be abandoned. One of the most important components of Miami’s drug policy is its needle-exchange program, and Florida’s Miami-Dade County boasts one of the lowest overdose mortality rates in the country. From July 2022 through June 2023, the program collected more than 12,000 more needles than it distributed, and it helped seventeen percent of its clients enter into treatment. If you visit the website for Florida’s Harm Reduction Collective, which runs Miami’s needle exchange, the first thing you will find are resources for recovery. By contrast, San Francisco’s harm-reduction organisations offer no information about addiction treatment, and the same goes for other cities at the top of the overdose-mortality list.

Tom Wolf, a former addict and current recovery advocate in San Francisco, adamantly supports needle exchanges, but he is a prominent critic of harm-reduction orthodoxy. He does not oppose harm-reduction policies, per se, but he thinks of it differently to most San Franciscans. “Harm reduction is a set of tools,” he explained to me, “but it doesn’t make good policy. Policy should be recovery.”

II. The Flawed Safe-Sex Analogy

Harm reduction as drug policy gained steam partly because of its resemblance to the successful safe-sex movement. Recognising that total abstinence from sex among teenagers was an unrealistic goal, many states started teaching young people how to reduce the risk of pregnancy and disease during intercourse. They handed out condoms and birth control while educating teens on the risks that accompany unprotected sex.

The safe-sex strategy seemed to work. States that adopted a safe-sex approach to sex education average about thirteen teen pregnancies per 1,000 females, while abstinence-only states see nearly seventeen teen pregnancies per 1,000 females. Incidences of sexually transmitted disease show similar disparities between safe-sex and abstinence-only states.

The success of the safe-sex campaign gave a major impetus to the harm-reduction movement for drug users. As the country was in the throes of the Drug War, the abstinence-only approach to drug policy was not working. The more the federal government fought to eradicate substance abuse, the more widespread it seemed to become. Adopting the same policy towards drugs that worked so well for teenage sex seemed to make sense.

But this analogy suffers from a serious flaw. Unlike substance abuse, sex is fundamentally good. It is necessary for species survival, and the libido is inherent to the human experience. We can try to teach self-control, but we cannot eradicate the sex drive (short of castration), nor would we want to. The abstinence-only movement never taught people to live a life of celibacy; it taught them to wait until they were married and ready to have children. We treated sexual harm-reduction as an alternative to abstinence because sexual abstinence was only meant to be temporary anyway.

Somewhere along the way, though, the harm-reduction movement for drugs started to trend in the same direction, even if unintentionally. Education and outreach seemed to forget that recovery was supposed to be part of the formula. Unlike with sex, total abstinence from hard drugs should be the end goal of harm reduction, but in places like San Francisco, harm reduction is treated as an alternative to recovery.

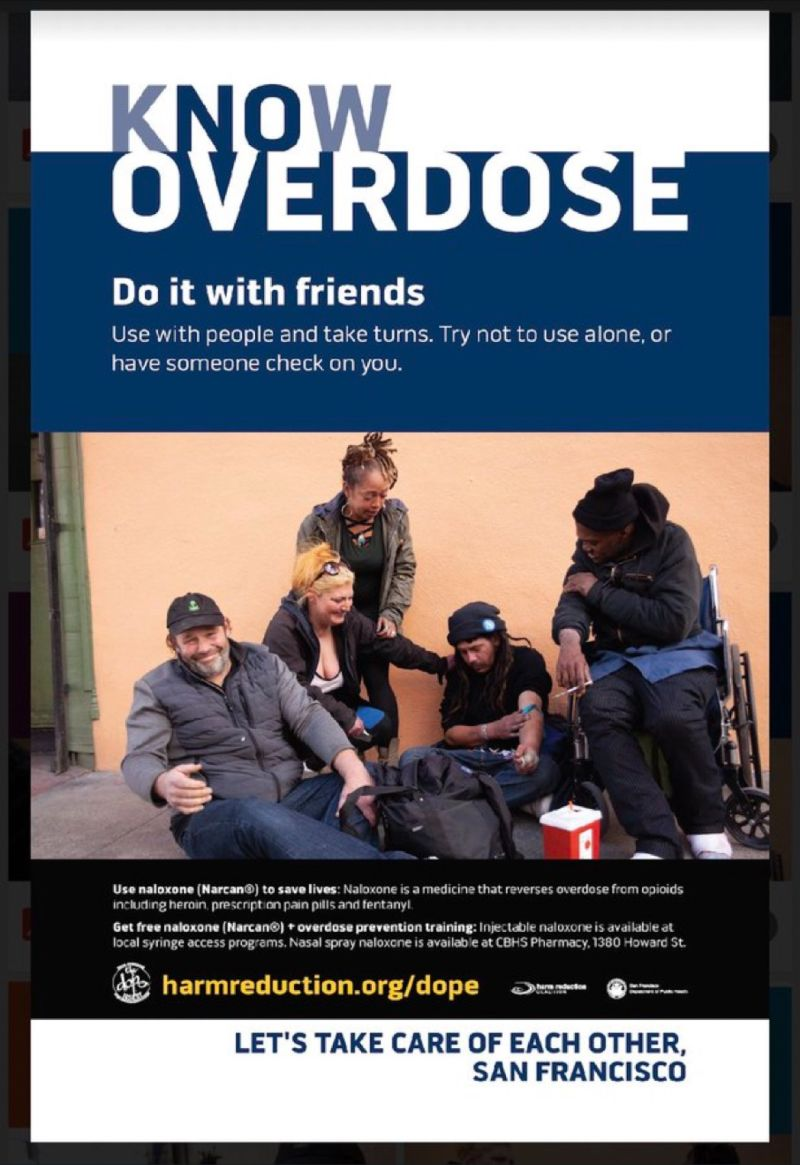

The drift in San Francisco’s harm-reduction movement has produced downright dystopian outreach efforts. Exhibit A might be the “Know Overdose” campaign, which plastered the city with posters and billboards to encourage social drug use. One poster reads, “Know Overdose. Do it with friends. Use with people and take turns.” The poster is adorned with a photo that seems like a creepy parody of college catalogue pictures: a pair of smiling harm-reduction workers helping three men take turns shooting up. The image has not aged well. According to Tom Wolf, of the three men featured on the poster, two have since died from accidental overdose and the third is in prison for stabbing his dealer.

The “Know Overdose” campaign reflects how thoroughly harm reduction has been divorced from recovery in many progressive cities. In 2013, researchers studying the effects of marketing on tobacco users found that “daily [point-of-sale tobacco] exposure was significantly associated with lapsing when craving was low.” Smokers who were trying to quit, in other words, could enter a store with no nicotine cravings and leave with a pack of cigarettes. All that was needed to trigger the onset of cravings was to encounter familiar reminders that cigarettes existed. To the recovering opioid addict, by extension, a harm-reduction poster that preaches “do drugs with friends” functionally operates as a subliminal message to simply “do drugs.”

Addicts in San Francisco are immersed in an environment that reinforces substance abuse. San Francisco was among the first cities in the country, for example, to adopt “Housing First” as its homelessness policy, which ties grants to a harm-reduction mandate. Housing First funnels money into “permanent-supportive housing,” which is prohibited from imposing sobriety requirements on tenants. Homeless addicts—and there are many in San Francisco—predominantly live on the streets, where public consumption and open-air drug markets are tolerated, but recovering addicts placed in housing are still forced to share hallways with active users and dealers. It is hard to imagine a worse environment for somebody trying to recover from addiction.

Despite their attachment to the harm-reduction philosophy, permanent-supportive housing facilities are the site of an astonishing number of overdose deaths. A study from the University of Pennsylvania found that more overdose deaths among people experiencing homelessness occurred in supportive housing and shelters than on the streets. In San Francisco, overdose deaths in these facilities are so common that they sometimes hold joint funerals for residents, honouring as many as seven people at a single service. Venus Mason, who lost her mother to an overdose, voiced her exasperation with having her placed in such an environment. “She was on drugs for 32 years,” she said of her mother. “Why put her here?”

Even when addicts decide they want to stop using, the help they find may actively deter them from seeking treatment. Staff at GLIDE are only allowed to discuss recovery if a client brings it up, but even then, they are given no training or materials to direct people to treatment services. Instead, GLIDE teaches them to pursue “more realistic goals.” Here is the safe-sex strategy fully realised in drug policy—harm reduction positioned as an alternative to abstinence, instead of a gateway to recovery.

III. Gateways to Recovery

In 2022, San Francisco opened the Tenderloin Linkage Center, a supervised injection facility (SIF). Its stated purpose was to prevent overdose deaths and refer people to treatment services (hence the “linkage” aspect of the clinic). When it opened, the official press release emphasised the centre’s role in “connecting people to short- and long-term services, care, and programs” as its primary function, but critics raised concerns that the clinic was little more than a glorified drug den. The Tenderloin Center made national news after a visitor inquired about recovery services and was reportedly told, “We can help you do drugs. But if you want help getting off drugs, you’re gonna have to come back tomorrow.”

Supervised injection facilities (SIFs) remain highly controversial, but interest in them has ballooned over the past decade. Advocates passionately defend the role that SIFs play in promoting recovery, invariably pointing to the documented success of Insite, North America’s first SIF, which opened in Vancouver in 2003. One widely cited study found that enrolment in detoxification services increased by thirty percent during Insite’s first year of operations, and its opening was also associated with increased rates of long-term treatment.

Guy Felicella is one beneficiary of Insite, having been revived four times after overdosing at the facility before finally getting clean. “The last time that I overdosed at that facility was February 18, 2013,” he told me when we spoke. He was oxygen-deprived for eight minutes, but when he woke up, he asked the nurse, “Why are you crying?” She responded, “Because I care about you, Guy.” At that point, Felicella burst into tears and agreed to start treatment for his addiction—not for the first time, though this time it would stick.

Felicella’s story illustrates how SIFs can promote recovery, but it also reminds us that recovery is not an automatic byproduct of their existence. A 2011 study of Insite recognised that “a primary causal mechanism” for entry into treatment was regular contact with an addiction counsellor. When I asked Felicella how important this was to his recovery journey, he answered, “It was vital.” SIFs that neglect to offer positive encouragement for recovery will predictably see fewer clients accept treatment.

The immediacy and ease with which SIF clients can access recovery services directly corresponds to the rate at which they enrol in treatment. Since 2007, Insite has essentially operated as an appendage to a second-floor detoxification centre, Onsite, which is run by a team of doctors, nurses, mental-health counsellors, and social workers. Proximity is part of its strategy for recruiting clients. “Because Onsite primarily transitions people from Insite,” its website explains, “it is successful at reaching people at the moment they decide to make a change” (emphasis added). That moment of vulnerability when somebody is first revived from an overdose is often the trigger for the decision to get clean, but that feeling can wane quickly as the cravings of addiction begin to creep back up.

Felicella is frustrated that people don’t talk more about Onsite when discussing Insite. “When I’d overdose,” he explained to me, “they would just immediately bring me upstairs”—then he quickly added, “if I wanted to.” It mattered that the decision to start detox was his to make. Studies consistently show that voluntary treatment has a higher success rate than compulsory treatment. But it also mattered that the staff at Insite, with whom he’d built relationships over the years, actively supported his decision to enter treatment.

Here, it seems, is a harm-reduction organisation that serves as a gateway to recovery. The most recent study of Insite followed a cohort of intravenous drug users in Vancouver and found that 11.2 percent enrolled in Onsite’s detoxification services over a two-year period. However, the number jumped to 23.7 percent when narrowing the cohort to individuals who had recently used Insite’s supervised-injection services. In total, nearly ninety percent of Onsite’s clients during the study period came through Insite (131 out of 147 enrolments).

However, most SIFs are not co-located with a detoxification centre, so they can only issue referrals to offsite treatment. A study of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injection Centre in Australia found that the clinic referred sixteen percent of its patients to offsite healthcare, and sixteen percent of those clients followed through on the referrals to accept treatment for their addiction. That amounted to less than three percent of clients accepting recovery services. The lacklustre results of Sydney’s referral program are consistent with another study that found drug addicts were nearly three times as likely to accept on-site healthcare than they were to follow through with referrals for treatment elsewhere. Even a low treatment rate, though, means the facility still helps some people take their first steps toward recovery.

The Tenderloin Center ostensibly followed the referral model, though it did not hire nurses or addiction counsellors. Instead, it hired inexperienced “heath-service aides” and trained them in how to administer naloxone, the drug used to reverse opioid overdoses. And as with other harm-reduction organisations, staff were prohibited from mentioning recovery unless a client asked about it first. Consequently, an audit of the clinic’s records showed that only one out of every 300 clients ever received a referral for treatment, and there was no follow-up regarding referral uptake. If we assume it matched Sydney’s uptake rate, that would mean only 0.05 percent—one-twentieth of one percent—of Tenderloin Center clients entered treatment.

In fairness, the Tenderloin Center successfully reversed more than 300 overdoses before it was shut down, but its abysmal track record of linking people to treatment makes it easy to understand why so many recovery advocates celebrated its closing. When harm reduction is positioned as an alternative to treatment, it is hard to blame people for viewing it as incompatible with recovery. But it does not have to be this way.

Felicella laments the shuttering of the Tenderloin Center, but he does not deny its failings. Instead of closing it, he wishes it had been reformed along the Insite-Onsite model, with recovery as an overarching goal that guided its operations. What stands in the way of a recovery-oriented model of harm reduction in San Francisco, though, is culture.

IV. Cultivating a Culture of Recovery

In the 1990s, Portugal was hit with a severe opioid epidemic. The capital city, Lisbon, was considered the “heroin capital of Europe.” Since punitive drug policies were not working, in 2000, the Portuguese government decided to decriminalise drugs and start following harm-reduction strategies. The country subsequently saw an impressive turnaround in its drug problem. In less than two decades, the number of heroin addicts in the country had been reduced by 75 percent, and drug-related deaths had been reduced to the lowest levels in the European Union.

Portugal did not change its attitude towards drugs, and the country’s new policies still reflected an anti-drug ethos. The country decriminalised drugs, for example, but it still does not tolerate open-air drug markets or public consumption. The country provided clean needles and safe-injection facilities, which were used as gateways to connect people to addiction treatment and other services. When Portuguese police caught people with a personal supply of drugs, they sent them to a local Commission for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction, staffed by legal, healthcare, and social-work professionals. Recovery was a measure of success for harm reduction policies in Portugal, and it worked spectacularly.

In his book Addiction: A Very Short Introduction, Stanford psychology professor Keith Humphreys compares the drug problem in San Francisco to that of Lisbon. San Francisco tried to mirror Portugal’s drug policies, but it achieved opposite outcomes. “Unlike the Portuguese city,” Humphreys notes, San Francisco “has high rates of drug use, open air drug markets, significant drug-related disorder, and high rates of overdose.”

How can two cities that follow similar policies produce such wildly different outcomes? According to Humphreys, “the difference is probably cultural.” Ever since the 1960s, San Francisco has not only tolerated drug use, but has celebrated intoxication and fostered a pro-drug subculture. Portugal, on the other hand, decided to tolerate drug use legally, but drugs remained stigmatised culturally.

One of the core principles of harm reduction is destigmatisation, but San Francisco seems to have taken this concept far beyond its original purpose. Harm-reduction facilities like Insite practice destigmatisation because they do not want to discourage people from using their services. The idea was that it should serve as an oasis to provide drug users some respite from the broader social stigma against substance abuse. But if destigmatisation is made near-universal—as is the case in San Francisco—how can the principle draw people into harm-reduction services?

Even today, with fentanyl invading the drug supply, many San Franciscans cling to the city’s tradition of celebrating indulgence and intoxication. In 2023, activist Nova Shultz organised the Drug User Liberation Collective, which plastered the city with posters that read “Downtown is for Drug Users”—a response to what he saw as the undesirable shift among city leaders toward anti-drug policies. Less than a year later, Schultz died from an overdose

Cultural values seep into policy, often in ways we are not aware of. In the context of San Francisco’s pro-drug culture, harm reduction morphed into strategies for sustaining addiction. When California decriminalised drugs in 2014, San Francisco (and many other cities) declined to even police drug activity in public spaces. The policy was largely identical to Portugal’s, but San Francisco’s pro-drug culture guided implementation in the opposite direction. Culture similarly influences practices across the harm-reduction spectrum, from the “Know Overdose” campaign promoting social drug use to the harm reduction kits that include smoking supplies.

The debate over harm reduction largely falls along a simple binary—people are either all for it or completely against it. As is often the case with political controversies, though, the reality is more complex. “Harm Reduction” encompasses highly varying policies and practices. We should resist the temptation to treat every activity that falls under this umbrella equally. Even the fiercest critics of harm reduction generally favour making naloxone more accessible, which itself is a harm-reduction approach.

Yet too many harm reductionists treat the philosophy like religious orthodoxy, assuming without scrutiny that every so-called “harm reduction” policy successfully reduces harm. The high rates of overdose death in San Francisco and similar cities make it clear that when harm reduction settles for merely sustaining people in their addiction, they fail to do even that. Fentanyl is much more lethal than heroin, and now animal tranquillisers—which cannot be reversed by naloxone—are further contaminating the drug supply. In such an environment, maintaining people in their addiction is an increasingly short-term solution.

Here, then, is the rub: harm reduction works best when it is recovery oriented. The oft-professed purpose of harm reduction is to keep people alive long enough to recover from their addiction, which means that proper harm-reduction policies should aim to encourage treatment and maintain sobriety as much as to prevent drug-related deaths. Even if we believe that some drug users will never realistically recover—a common claim among harm-reduction advocates—we should reject this as an operating principle. Harm-reduction practices must always be guided by the belief that recovery is both possible and desirable for every person struggling with addiction.

Correction: An earlier version of this essay misstated Gina McDonald’s name. Quillette regrets the error.