History

Another JFK Assassination Nothingburger

Jefferson Morley’s dogged pursuit of a CIA connection in Miami is all smoke and no fire.

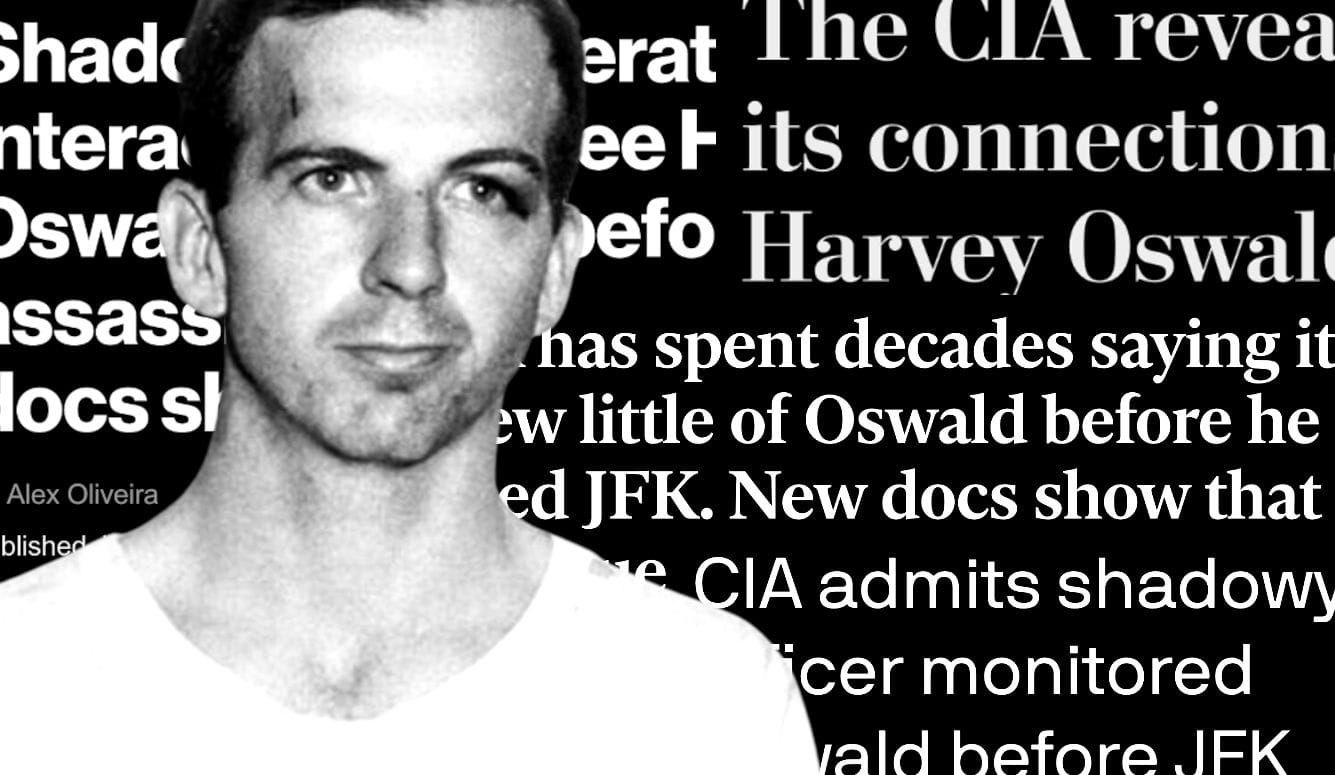

On 15 July, a headline below the fold on the front page of the Washington Post claimed that “Documents Show CIA Had Connection with JFK’s Assassin.” (Online, the headline over Tom Jackman’s report reads, “The CIA reveals more of its connections to Lee Harvey Oswald.”) Axios headlined their story “CIA admits shadowy officer monitored Oswald before JFK assassination, new records reveal.” The New York Post ran with “Shadowy CIA operative interacted with Lee Harvey Oswald months before JFK assassination, newly released docs show.” And Congresswoman Anna Paulina Luna tweeted, “The CIA lied to Congress,” adding that Lee Harvey Oswald “was a patsy used as a cover for multiple shooters in the assassination of JFK.”

Is any of this true? It is not. Yes, a number of new documents have just been released. But—excitable newspaper headlines notwithstanding—these documents tell us nothing new about the JFK assassination at all.

This particular thread in the JFK assassination tangle leads us back to Jefferson Morley, a Washington Post reporter who fell down the conspiracy rabbit hole when he began chasing a story in the early 1990s. At the time, the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB)—a citizen panel established after the release of Oliver Stone’s conspiracy thriller JFK—was busy declassifying assassination-related documents. Morley’s eye was caught by an incident involving Lee Harvey Oswald in New Orleans during the summer of 1963.

Oswald had defected to the Soviet Union in 1959 and returned to the United States in 1962 disillusioned by his time there. He was still a Marxist, but he had now transferred his affections to Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the hope that this revolution would succeed where the Soviet model had failed. Oswald had trouble keeping a job in Dallas, so in April 1963, he moved to New Orleans, where he had been born, to find work. In early June, he ordered a number of handbills emblazoned with the words “Hands Off Cuba!” in block capitals. The bills were supposedly the work of the New Orleans branch of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, but in reality, Oswald was the organisation’s secretary and only member.

In August, Oswald visited a store managed by Carlos Bringuier, a delegate of the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil (DRE), a strident anti-Castro Cuban student activist group based in Florida. Oswald told Bringuier he wanted to join the fight against Castro and that he was trained in guerrilla warfare. The following day, he returned and left his Marine guidebook for Bringuier as proof of his commitment. But a few days later, Bringuier’s friends discovered Oswald distributing his pro-Castro leaflets on the streets of New Orleans. A fight ensued, and Oswald and three of his Cuban antagonists were arrested for disturbing the peace. Oswald pled guilty and was fined US$10. A week later, he was back on the streets distributing his leaflets again. He even made the evening newscasts.

Bringuier subsequently ran into William Stuckey, a radio broadcaster who focused on Latin America, and told him what had happened. Stuckey visited Oswald and then broadcast part of an interview. On 21 August, the station broadcast a debate between Oswald, Bringuier, and Edward Butler, executive director of the Information Council of the Americas (INCA), during which Oswald denied being a communist and described himself as a Marxist. After the debate, Bringuier issued a “press relief” [sic], and Butler also contacted the media, and the story was picked up by a few newspapers in Louisiana and Texas.

Oswald’s offer to help Bringuier and his anti-Castro organisation was obviously not sincere, and most likely a clumsy infiltration effort. That, at least, was Bringuier’s assumption. Oswald was already thinking of travelling to Cuba to help with the revolution, and he seems to have hoped that press coverage of his pro-Castro activities would impress the Cubans who were approving visas. He may have reasoned that infiltrating an anti-Castro group would make him an even more attractive candidate for Cuban citizenship.

In any event, Bringuier wrote to his colleagues at the DRE in Florida about the incident with Oswald. After the assassination, they recognised Oswald’s name in the news reports and retrieved Bringuier’s correspondence from their files. Without getting permission from their CIA case officer, they called the press and claimed that Castro was behind the assassination.