Podcast

Can We Regulate Online Hate Without Killing Free Speech? With Dr Andre Oboler | Quillette Cetera Ep. 50

As antisemitism surges online and in the streets, online hate researcher Dr Andre Oboler joins Zoe to examine how conspiracy thinking, political ideology, and institutional complacency are fuelling hate—and what can be done to stop it.

In this episode, Dr Andre Oboler—CEO of the Online Hate Prevention Institute and a global expert on antisemitism, hate speech, and online extremism—joins Zoe Booth to unpack the surge in antisemitic hate speech since 7 October 2023.

Dr Oboler discusses recent antisemitic attacks on Australian synagogues, and his role as an expert witness in the landmark Wissam Haddad hate speech case, which tested the limits of Australia’s racial vilification laws. He critiques the failure of major social media platforms to moderate digital hate, and outlines the legal, educational, and community responses needed to address the rise in online antisemitism.

The conversation also tackles a difficult but essential question: How do we protect free speech while holding people accountable for inciting hatred and violence online?

Transcript

ZB: Could you tell our audience a little bit about what it is that the Online Hate Prevention Institute does?

AO: Okay. We were set up in January 2012, so we’ve been around for quite a while now. Our mission is to prevent harm to people as a result of online hate, and that extends from hate speech all the way through to extremism. At the really pointy end, we’ve done things like taking down manifestos and live-streaming videos from actual terrorist attacks—within hours of them occurring.

ZB: So when you say harm, you mean physical harm?

AO: It can be physical, it can be mental, emotional, et cetera. It’s the full gamut of psychological harms as well. We were set up as a harm prevention charity, which is a very particular type of charity under Australian law. The legislation basically defines the types of harm that harm prevention charities are meant to address. That ranges from suicide prevention, self-harm, and problem gambling—though that’s not usually relevant to us—through to bullying, harassment, physical assault. All of that can, in our case, be triggered by online content.

ZB: What are the main types of harm that you see?

AO: We deal with a lot of different types. When we first started, one of our early projects in 2012 related to racism against Indigenous Australians. There was a huge number of Facebook pages—driven by a small group of people—filled with “Aboriginal memes” that were deeply racist. They referenced things like people in remote areas sniffing petrol fumes—mocking a real health crisis—and included welfare-related slurs and commentary. The Human Rights Commission was responding, but we did the legwork, documenting the pages. Some of them were taken down, but others kept being re-uploaded—often in ways that weren’t immediately obvious as new pages. So it looked like nothing was being done. We produced a report.

Then there was a whole wave of what was known as “RIP trolling”—“Rest In Peace” trolling. Someone would die—often a child, tragically—and people would mock and harass the surviving family. In one extreme case, they set up a fake sympathy page. Family and friends joined, shared photos of the deceased child—and a week later, the trolls started defacing the child’s picture, turning it into a zombie, and posting deeply upsetting content. A second page was then set up calling for the first one to be removed—and the same trolls were behind that page as well. It happened all over again. You can imagine the distress that caused the family and the community.

ZB: God, people choose to spend their time in bizarre ways. I just can’t imagine why anyone would want to do that. From what I can see—I’ve seen a lot of this content you’re talking about—it often seems like a way to signal to your group that you’re the funniest poster, or that you take the biggest risks, say the most outrageous or transgressive things. Have you looked into the motivations behind this kind of behaviour?

AO: That’s typical troll behaviour, and yes, it accounts for some of what I’ve described. But a very large part of our work—particularly since October 7—has been on antisemitism, and also Islamophobia. Both rose sharply, and that kind of content isn’t usually trolling. It’s different. The people posting that feel they have a moral imperative to say and do what they’re doing. But sometimes that content literally calls for people to be killed. Sometimes it spreads conspiracy theories. It normalises hate—first online, then in society. We’ve seen both antisemitism and Islamophobia rise, though antisemitism is about 2.4 times higher. It was already higher before October 7. We’ve been monitoring it continuously. It peaked in the months afterwards, dropped a little, but has stayed well above pre-October 7 levels. We’ve just completed another sample—we haven’t published it yet, you’re the first to hear this—but it’s rising again. Not quite at the post-October 7 peak, but it’s the highest it’s been since.

ZB: Can you explain the difference between antisemitism and other forms of racism?

AO: It’s an interesting question. Some forms of antisemitism are exactly like other forms of racism. For example, dehumanisation is common across many groups. Antisemitic dehumanisation sometimes takes specific forms—such as comparing Jews to rats—which traces back to Nazi propaganda and other historical sources.

But some aspects of antisemitism are quite different from most racism. For instance, the notion that Jews are rich, powerful, or intelligent—these are framed as negative accusations. “Jews control the government” or “control the banks” is a classic example. These narratives twist attributes that might otherwise be considered positive.

In the US, racism is often defined as discrimination plus power—so racism must come from someone with power against someone without it. If you’re arguing that the “problem” with Jews is that they’re powerful, then people frame it as “punching up”—which supposedly means it’s not racism. That’s where Jews are sometimes excluded from anti-racism efforts. They’re told that their racism “doesn’t count” because of the stereotype that all Jews are wealthy or powerful.

ZB: Yeah, and that fits with the most popular ideology in our institutions at the moment—based on this critical theory where all social interactions are seen through a power hierarchy, depending on whether you’re a man or woman, white or black, etc.

AO: Yes, there’s some truth in the argument about hierarchies and “punching up” or “down.” But what’s often ignored is the power of the collective—the power of the mob. When people gather in a group, even those “punching down” can wield considerable power, and that gets completely discounted in these frameworks.

AO: I was asked on ABC Radio whether a pro-Palestinian protest and encampment at a university is antisemitic. I said that’s not a very useful question, because it may or may not be antisemitic—just like anything else. We need more detail. For example, if protesters see someone who looks Jewish walking past and decide to go and harass that person—then yes, that’s antisemitic. If a protest goes on for an exceptionally long time and creates a hostile environment—beyond what a reasonable person would consider a fair opportunity to express a view—and especially if it occupies space that prevents other causes from also expressing their views, then we have a problem.

ZB: Mm-hmm.

AO: That’s what we saw with some of the encampments.

ZB: Yeah. And I know you’ve been studying the synagogue attacks—we’ve had a few in Australia. And not just synagogue attacks but also attacks on Jewish kindergartens and other institutions.

AO: I’ll just step in there. They thought the kindergarten was Jewish, but it actually wasn’t. That particular kindergarten wasn’t even Jewish—it was targeted by mistake. We’ve seen Jewish schools targeted, and in one case, the old house of a Jewish community leader was attacked. The current resident has absolutely nothing to do with the Jewish community—but it still counts as an antisemitic attack. If someone is targeted because they or their property are thought to be Jewish, that’s still motivated by anti-Jewish hate. So it’s still antisemitic.

ZB: So what do we know about those attacks?

AO: Our report on the synagogue attacks does discuss the attacks themselves, but only briefly. What it really focuses on is the public response on social media. In both the ADAS attack and the East Melbourne attack, which we documented at the time, there was an immediate online response denying it was real. This is the same category of denialism we see with US school shootings—like Sandy Hook—and is more aligned with Holocaust denial than with most other forms of antisemitism.

People claimed it was a false flag, staged by the Jewish community. Others blamed Mossad, saying they wanted to manipulate opinion about Israel. Still others blamed the state government or ASIO or the AFP, suggesting it was an excuse to bring in draconian new laws. All of this denies that a real community was subjected to a violent hate incident. The goal is to withhold sympathy from Jewish victims and to prevent antisemitism from being acknowledged—because the people promoting this want to continue engaging in antisemitic rhetoric and actions without consequence. It’s an enabler, in the same way Holocaust denial enables Nazism to re-emerge.

ZB: Yeah. I guess my question with all of this is—I’m a heavy user of social media. I’ve been on Twitter and Reddit since I was a teenager. I’ve seen a lot of hate—not as much as you, obviously—but some despicable things. I’ve even been a target.

The best example is when I posted a photo of myself with my fiancé’s now-deceased grandmother, who was a survivor of Bergen-Belsen and the death marches. I shared this photo on Twitter—it became my most engaged-with tweet ever. Most of the reactions were positive, lots of likes, people happy to see a beautiful Holocaust survivor enjoying her life. But it also got ratioed, as they say, by a huge number of trolls and Holocaust deniers. It was really disgusting. I’m glad Olga—the survivor—never saw it.

I personally chose to ignore it. I have most notifications from people I don’t follow muted, so I don’t have to see what horrible people say. I guess my question is—because that’s how I dealt with it—what’s the broader impact? I didn’t experience real-world consequences, aside from learning not to post as much online. But where does your research lead? Because people will be hateful online when they feel they can. What are the real-world consequences?

AO: I want to go back to something you just said. After the East Melbourne synagogue attack, the Prime Minister put out a post condemning it—and that post was ratioed. That’s a statement from the head of government about an attack on a religious building. And instead of being met with support, it was flooded with hostile comments. That’s a really concerning sign of where antisemitism is in this country.

ZB: I guess playing devil’s advocate, I’d say—Andre, I’m sure there was a lot of support too. I’m sure many people liked the post. And perhaps the more “normal” people—those not on Twitter—were supportive. Should we base our view just on the hate we see?

AO: Well, what you’re arguing is that ratioing isn’t a reliable measure—and that’s a fair point. But it’s much easier to like a post than it is to write a hostile comment. So when a post is flooded with comments rather than support, that suggests there’s a suppression of the support you would normally expect when the Prime Minister says there’s been a tragedy and the public should support the victims. And that support is absent.

ZB: I guess my question is: how much should we trust online hate? How much does online hate affect the real world? I know it’s a false dichotomy—“online” versus “real”—but you know what I mean. Do you get what I’m trying to ask?

AO: Yes. And there is a very direct line between what happens online and what happens offline. Online spaces are where hateful attitudes are normalised. Those narratives become embedded in people’s minds, and then they feel they have permission to act on them in the real world.

After the synagogue attacks, we saw protests escalate. We saw things like the attack on the Miznon restaurant. That wouldn’t have happened without online discussion first identifying it as a target. It was being pointed out as a location in the day or so prior. And then, more broadly, there was this online environment encouraging people to go beyond peaceful protest—urging them to “up the ante.” That normalisation and encouragement is what leads to real-world harm.

ZB: Yeah, I definitely see that happening. And you can see it in other areas too. With fashion, for example—if a trend goes viral on TikTok, like how to wear your bikini or trousers—you’ll see girls start dressing that way in real life.

AO: On the topic of fashion—let me share something from the report.

[Note: visual aid referred to.]

AO: So, in response to the synagogue attack, someone commented, “False flag. No way someone who seriously wanted to commit this crime would do so wearing this outfit. The suspect is very likely a Mossad agent and the intent of this false flag is obvious.” Others commented things like, “Probably self-inflicted. Blame Muslims like in the UK. The Zios did it.” Or, “I wouldn’t be surprised if the Israelis in Melbourne burned down their own synagogue. They love to play the victim.”

ZB: They say “Israelis,” not “Jews,” right? [sarcastic tone]

AO: In reference to a synagogue, yes. It’s a form of wordplay. We also see posts that refer to “Zionists.” But when the target is a synagogue, we’re really talking about Jews. It’s an effort to avoid being accused of antisemitism—by claiming they’re only criticising Zionists, or Jews who support Israel, or Jews who believe Israel has a right to exist.

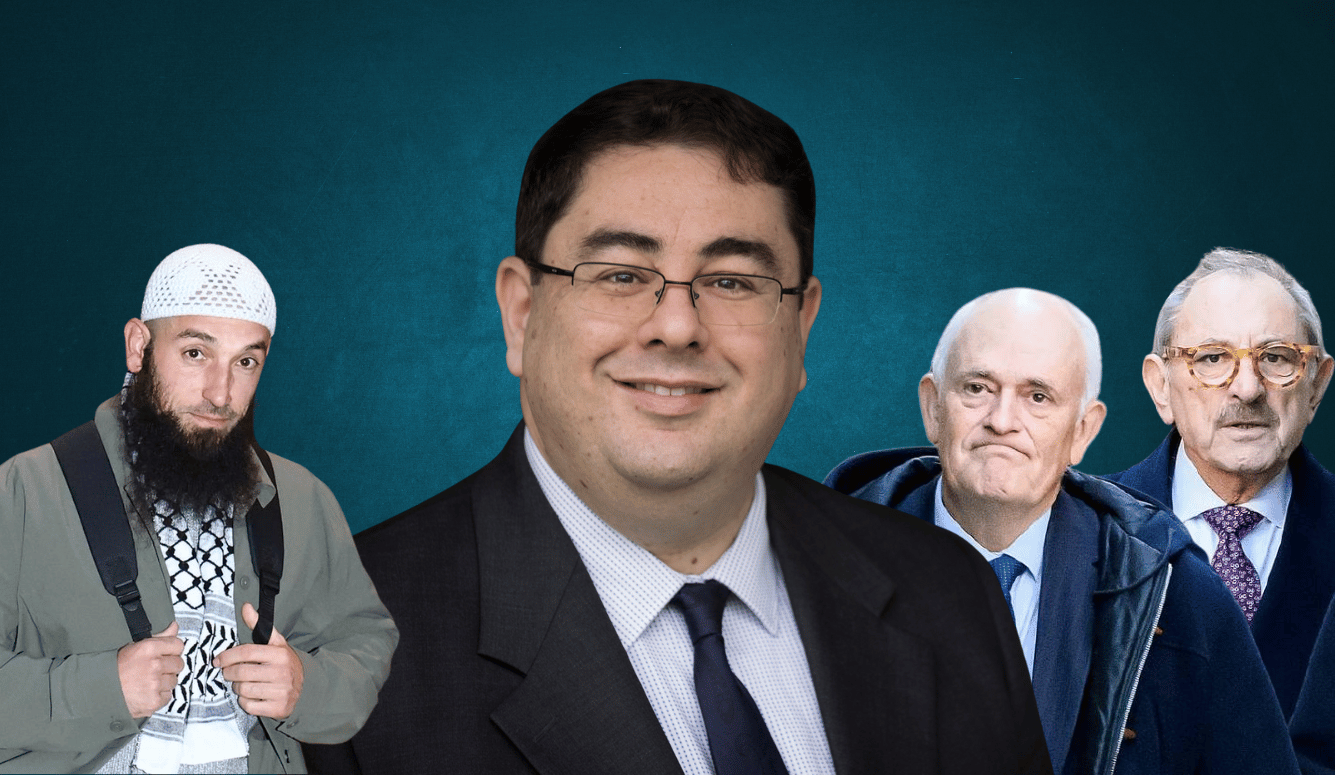

ZB: That leads me to another topic I wanted to discuss with you, which is that you were an expert witness in a recent case that received a lot of media coverage—Wertheim and Haddad. Could you explain that case to our audience? Most of our readers and listeners are in North America, so they may not be familiar with it.

AO: Certainly. First, I should say that Peter Wertheim and Robert Goot—who brought the case—are senior figures in the peak Jewish community body in Australia. Peter Wertheim is co-Chief Executive, and Robert Goot is a Vice President. They brought this case on behalf of the wider Jewish community.

Wissam Haddad is a Muslim preacher. He made a number of speeches in a mosque, which were recorded and shared on social media. He argued that these speeches were responses to the situation in Gaza—political commentary—but they contained quite a few antisemitic tropes and stereotypes.

ZB: Such as claiming that Jews are descendants of apes and pigs, for example?

AO: Yes, that was certainly in there. But also claims that Jews are untrustworthy, that they control the media, that they are responsible for conflict with Muslims. There was a wide range of material—some of it rooted in European antisemitism, going back to the Middle Ages, and some from Islamic antisemitic traditions.

Other Muslim leaders have rejected those interpretations. While some of those statements appear in scriptural texts, he presented them as historically accurate and still true today—drawing direct conclusions like “we mustn’t trust Jews,” and repeating a variety of antisemitic stereotypes.

The case first went to the Australian Human Rights Commission, which doesn’t make legal rulings but tries to facilitate reconciliation between parties. When that failed, the matter was taken to court. A number of Haddad’s speeches were submitted. I provided an expert witness statement explaining the link between the specific content and recognised forms of antisemitism—where these ideas come from, how they’ve been used, and why they are harmful.

The report I submitted was over sixty pages long and included hundreds of references. It’s been made public by the Federal Court of Australia. One of the things I did in the report was to include links to MEMRI—the Middle East Media Research Institute—which has documented many of these same phrases and shown that they are widely recognised as antisemitic, both in academic literature and in statements by political leaders around the world. I used that to demonstrate that these were not merely offensive or controversial statements—they were recognisably and historically antisemitic.

There was an attempt afterwards to spin the decision. But the court used the word “overwhelmingly” to describe the plaintiffs’ victory. Mr Haddad was ordered to pay costs and to publish a statement acknowledging that he was found to have engaged in racial discrimination.

However, the judge also reviewed some of the examples and ruled that those particular examples were not antisemitic, saying instead that they were political discussion—criticism of Zionism or of Israel as a state. I don’t want to say too much about that part, because I do disagree with some of the analysis. I believe that, had there been more discussion in court about those particular points, the judge may have reached a different conclusion.

After the ruling, we saw social media statements claiming that the judge had said this was a victory for Palestinian advocates, or that the court had ruled anti-Zionism is not antisemitism. To clarify: the judge did say that criticism of Zionism is not, in and of itself, antisemitism. But let me add, in my own words—not the judge’s—criticism of Judaism is also not automatically antisemitic.

Antisemitism is when hatred is directed at people because of their religion or identity. In the case of Zionism, when criticism crosses into hate and targets individuals for supporting Israel’s existence, then that becomes antisemitic. The judge tried to be clear about this. He wrote that criticism of Israel is not antisemitism, but attacking Jews because of what Israel does is antisemitism. Unfortunately, that second part has largely been ignored in public commentary. Instead, people are claiming that attacking “Zionists” is now legally protected speech—when in fact, many of those attacks are using Zionism as a code word for Jew.

Let me show you something else related to that. [Note: visual shared.]

This is a post from just a day or two ago on Facebook. The profile picture says “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” with an image of all of Israel and the Palestinian territories overlaid with a Palestinian flag. The post says: “If you believe that a ‘state’ committing genocide, ethnic cleansing and the deliberate starvation of a people has the ‘right to exist,’ then you are the problem.”

That’s clearly anti-Zionist—it denies Israel’s right to exist. But it’s also antisemitic, because it states that if you believe Israel has a right to exist, you—personally—are the problem.

ZB: But I’m not Jewish and I believe Israel has a right to exist. So why is it antisemitic?

AO: Because most Jews are Zionists. So this post is, effectively, saying that the majority of Jewish people are the problem. Other people might also support Israel, but this specifically targets a community that is protected under law. It blames them collectively for a complex political issue.

ZB: Hmm. Yes. And you wonder—are some of these people just that poorly educated that they don’t realise how important Israel is to most Jews? There’s a lot of misinformation.

AO: I had a long conversation with the person who made that post before they published it. At the time, they were saying they didn’t object to Jews believing Israel should exist. They didn’t object to Israel existing. What they objected to was the idea that people can be Zionists and not be held responsible for everything associated with Zionism.

They believe Zionism is responsible for everything that has happened to Palestinians since 1948, and everything currently happening in Gaza. So, if someone believes Israel has a right to exist, in their eyes, that person is also responsible for all the suffering. That’s collective guilt—holding people accountable for the actions of a government simply because of their identity or beliefs.

It’s like saying that if you believe Australia has a right to exist, you are personally responsible for every bad thing that has ever happened here, including actions by the government. It’s a kind of collective punishment—and that crosses a line.

ZB: Yeah. And it does feel like Jews are the only group to whom this kind of double standard applies. Although—you study online hate more than anyone—do you see this double standard being applied to other groups?

AO: We’re actually seeing it from two sides, but all of it pushes in the same direction. On the one hand, in discussions of antisemitism, there’s a widespread refusal to acknowledge that something could be both pro-Palestinian and antisemitic. There’s this idea that it has to be one or the other. So, if someone says something in the name of Palestinian advocacy, it’s automatically deemed not antisemitic—no matter how hateful or conspiratorial the language.

On the other hand, we’re now hearing about not just Islamophobia but also “anti-Palestinian racism.” The argument is that people are being investigated at work or having reputational damage because of their social media posts—and that this is anti-Palestinian racism.

So, in one case, the argument is: nothing can be antisemitism. And in the other: everything is anti-Palestinian racism. There’s no allowance for nuance or for legitimate complaints in either direction.

ZB: Yeah. Don’t you think that the pro-Palestinian crowd would say exactly the same thing about the pro-Israel crowd? They believe they’re the ones being silenced and victimised—that Jews or Israelis or pro-Israel people always claim victimhood. But what does the evidence actually show?

AO: Look, I don’t think they believe that. I think they say it. In Melbourne, there have been continuous pro-Palestinian protests. There’ve been maybe one or two rallies against antisemitism—and even then, those were attacked as being pro-Israel events, even though they were very clearly about opposing antisemitism.

So there’s this effort to silence others—others who, I should say, are barely speaking—and then to claim victimhood when there’s any pause or interruption in a continuous stream of pro-Palestinian advocacy. I don’t think that’s a serious argument, but it’s certainly a popular one.

ZB: Yeah, and look—one of my biggest concerns, as someone who grew up in Newcastle with no connection to Jews, Israelis, or even really the Muslim community—is that a lot of everyday Australians, who don’t have a personal stake in this conflict, are being inundated with online content. And the vast majority of it, from what I’ve seen, is anti-Israel. Do you have stats on that?

My fear is that this constant marination in anti-Israel content online is, essentially, brainwashing people. So when they do eventually meet a Jew or an Israeli, they’ve already absorbed all these assumptions and prejudices. They’ve been primed.

AO: Yeah. I’m just looking down at my phone here. I can’t share this one on screen, but it’s from a public conversation I saw online. A regular person—clearly someone who has absorbed a lot of antisemitism—wrote that the food crisis in Gaza was due to “repugnant Jewish supremacy at its finest”. They added: “At least you’re honest and don’t bother to hide it. Pure, unadulterated arrogance. Mazel tov.”

That was a public comment. The person being attacked replied and said, “You’re making antisemitic assumptions—you know nothing about me.” The original poster responded: “Antisemitism is a vexed term, my love. Arabs also speak Semitic languages. You’re Ashkenazi with zero ties to the Holy Land. You’re an imposter. See, I know who you are.” There are a lot of people saying similar things. This person went on to promote a whole host of conspiracy theories, including the Khazar theory—the claim that Ashkenazi Jews aren’t “real” Jews, and that Palestinians are the true Semites. This is part of the broader conspiracy thinking: that Jewish people aren’t real Jews, that the media can’t be trusted because it’s “controlled by Jews”—which is a classic trope from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

In Australia, we know who controls our media. There’s not a lot of diversity in ownership—but the conspiracy theory persists: that the Jews are behind everything, even when the facts clearly contradict that.

ZB: Yeah. There’s always an answer for everything.

AO: Exactly. And this is being absorbed by people who may not have encountered antisemitism before, but who—through discussions about the Israel–Palestine conflict—are now being exposed to centuries-old antisemitic tropes. These narratives are spreading like wildfire through social media. They’re going viral.

ZB: Yeah. And I’m always reluctant to draw comparisons with 1930s Germany, but—without being an expert—it does seem eerily similar. Back then, rhetoric and ideas slowly became normalised over time. So that when really bad things started happening to Jews—when they were being physically assaulted—there was already a justification in place. People had been groomed.

AO: Or even just a sense of indifference—that it’s not a real issue. After the recent synagogue attacks, for example, windows of Jewish businesses were smashed. The same night. That’s literally what happened during Kristallnacht.

ZB: So, what can be done?

AO: You do ask the easy questions!

The tech companies have massively reduced their capacity to deal with online hate—especially over the last six months. That includes both the AI systems and the human trust and safety teams.

We recently analysed transparency reports from the platforms themselves—and you can see the change very clearly. They’ve even said so outright. Their rationale is that they’re improving freedom of speech by reducing the number of false positives—things that are removed by mistake. But to reduce 200 false positives down to 100, they’re now letting 10 million harmful posts stay up instead of 1 million. The calibration is completely wrong.

ZB: To get back to basics, how does moderation actually work on Meta and X, for example?

AO: Well, in short—on Meta it could be improved, and on X, it doesn’t work at all. That’s the simple answer.

But let’s break it down. Moderation happens at different levels. On Meta platforms—mainly Facebook and Instagram, but also Threads and WhatsApp to a lesser extent—there are different layers.

First, if you’re running a page or posting to your own profile, you have control over what appears there. If someone posts abuse, you can block them. You can delete comments. That’s all user-level moderation.

The next level is when something is happening in a space you don’t control. In that case, you can report it to the platform. In the past, those reports would go to human teams around the world. Now, they mostly go to AI systems. And, generally speaking, the AI is now rejecting almost all complaints.

And if the AI rejects your complaint, you’re then given the option to request a review. Sometimes that goes to a human—but it appears that, in many cases, it just goes back to the same AI. And I don’t understand how that’s helpful. If the AI said no the first time, why would it change its mind the second time? It’s a machine—it doesn’t change its reasoning.

ZB: But even before that—imagine I go to post something, say nudity or gore. There are filters that recognise that automatically, right?

AO: Yes, there are filters. But those systems have been wound back. Facebook used to catch around 95 percent of hate speech before it was even posted—automatically. So, you’d post something, and it would be reviewed by the system before anyone saw it. That’s now been significantly reduced. The systems are still there, but very little is automatically removed.

ZB: But with images, they’re still automatically blurred or removed, right?

AO: Yes, but this highlights something interesting about the US context. When it comes to nudity, the US is much stricter than it is with hate speech—even with incitement to violence.

On the same day that Facebook announced it wouldn’t remove Holocaust denial, they also announced they were banning all pictures of breastfeeding mothers—because, apparently, that was inappropriate nudity. There was a huge backlash about the breastfeeding issue, and Facebook quickly reversed its policy.

But the position on Holocaust denial lasted for over a decade. It only changed relatively recently—when they introduced a policy that said they would no longer allow denial of mass casualty atrocities. That included Holocaust denial and also Sandy Hook conspiracy theories. But it took more than ten years of campaigning by various organisations to get there. And during that time, Holocaust denial—and with it, antisemitism—spread widely on the platform.

ZB: What about the argument—one that I myself have made in the past—that I’d rather know who the Nazis are. I’d rather know where they are and what they’re saying.

AO: The problem with that logic is that social media isn’t just a neutral space—it’s an amplifier. So you could say, “Well, if someone’s going to be violent, I’d rather they say it so we can catch them.” But imagine you then place that person in a room full of automatic weapons and say, “Feel free to try them out.” That’s not the same scenario.

There’s a level of acceleration and harm that social media brings. So we need different rules for social media than we do for society at large. YouTube, for example, often doesn’t remove content—but it removes sharing features, disables likes and comments, or demonetises the video. In other words, the content stays up, but it’s made invisible and unprofitable.

Now we’re seeing people adapt to that. They upload the content to YouTube as storage, and then use X, Gab, or Telegram to actually spread it. So they’re working around those restrictions. But frankly, if content is harmful enough to have all the social features stripped from it, it probably shouldn’t be hosted at all. It adds no value to public discourse.

ZB: I know—and I agree. But then there’s this question of how we define “harm.” Don’t we all define harm in different ways? It just feels like such a slippery slope.

AO: That’s a common argument, especially from the US. But it doesn’t really apply in Australia. We have laws against hate speech. We have legal frameworks, court cases, and precedents. Courts regularly make determinations about when someone’s conduct becomes unlawful—whether it’s assault, harassment, or vilification.

Hate speech is treated the same way. The law sets boundaries, and when necessary, the courts clarify them. We’ve had anti-racism laws since the 1970s. We’ve had religious vilification laws at state level, and now we’re getting more national consistency.

Parliament decides what’s protected. If the public wants change, they can lobby their MPs and push for reforms. That’s how our democratic system works.

ZB: But don’t these laws sometimes backfire? For instance, I hate Holocaust denial—I think it should be banned. But at the same time, I’ve publicly criticised people who say there’s a genocide happening in Gaza. Am I at risk of being targeted under these laws for denying a “mass casualty event”?

AO: You’re confusing platform policies with the law. I don’t think the platforms have determined that Gaza constitutes a mass casualty event in the legal sense. And there are strong arguments that what’s happening in Gaza doesn’t meet the definition of genocide—because intent is a key requirement. That term has been watered down a lot recently, but there’s definitely suffering in Gaza, and that’s part of a political debate.

As for the law itself—Australia doesn’t have a Holocaust denial law. What we do have is a law against racial vilification. The landmark case here was Jones v Toben, the first internet-related hate speech case in Australia.

Fredrick Toben was a well-known Holocaust denier. He ran the Adelaide Institute and made claims that Jews had fabricated the Holocaust, accused survivors of lying, and so on. The court ruled that this went beyond merely being offensive—it was abuse based on race and identity.

What happened to him? He was ordered to take the content down. That’s the penalty under 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act. It’s civil law, not criminal. So there’s no jail time. The penalties are limited: covering court costs, sometimes an apology. That’s it.

ZB: Quite different to the UK.

AO: Yes, the UK has a different standard of proof, and many of these incidents are dealt with as public order offences. Police handle them, and often it’s resolved with a relatively small fine.

In Australia, similar incidents could be dealt with under public order laws—but often the police don’t act. For example, we had neo-Nazis giving salutes on the steps of Parliament. Police didn’t stop it, because there were no specific laws banning Nazi salutes at the time. Parliament had to pass new legislation.

But existing laws could have been used. Police could’ve treated them as public nuisances and fined them [AU]$100. But because there weren’t serious penalties available, they didn’t act at all. That gap forced Parliament to introduce stronger laws.

ZB: So, what do you think should be done in terms of changes to laws?

AO: Well, I think the first step is to look at the role of social media. That’s where a lot of this problem originates. What we’ve seen over the last six months is a significant retreat by the platforms—cutting back both their AI enforcement and their human moderation teams. We need to return to a point where 95 percent of hate speech was automatically removed before anyone saw it.

And yes, people should have the right to appeal if something is wrongly removed—but that’s a better system than letting hate proliferate just to avoid the risk of over-censorship. At the moment, platforms are doing the bare minimum required to comply with EU regulations. They’re just scraping over the line to avoid legal trouble in Europe, but that leaves a massive volume of hate content circulating freely, harming societies around the world.

And the platforms are directly responsible for that.

AO: The second step is greater public education. We need a broader understanding of what different types of hate look like—particularly antisemitism, but also other forms of vilification. People need to be able to recognise hate and understand that it’s something they should speak up about.

If there’s an attack—whether on a synagogue, or, as we’ve seen in the past two weeks, a series of five attacks on one mosque—then all communities should stand together and say: this is unacceptable.

ZB: Which mosque is that?

AO: It’s the mosque in central Melbourne—it’s also the headquarters of the state’s peak Muslim body. They’ve had an envelope with white powder placed in their donation box, which led to an evacuation while it was checked for anthrax. People entering the mosque have been verbally abused. There have been five incidents in two weeks.

That’s not acceptable. And instead of denying that synagogue attacks are serious—or downplaying them—what we need is for every faith community to say: no one should be harassed for going to pray. No place of worship should be attacked. We used to have that kind of solidarity, but it’s broken down. And that speaks to a broader issue—not just about any single form of hate, but about the state of social cohesion in our society.

ZB: Do you have any stats on different types of antisemitism online?

AO: Yes, we do. We monitor a wide range of platforms—some that are favoured by the far-right, like Gab, and others that are more mainstream, like Instagram and TikTok. We have a classification system—a schema—for categorising antisemitism. It includes 27 different categories for antisemitic content.

We also have schemas for Islamophobia (eleven categories) and for other types of hate we frequently track. When we detect hate, we classify it according to the appropriate schema.

In terms of antisemitism, most of what we’re seeing is traditional antisemitism. That’s one of our four broad categories: traditional antisemitism, Holocaust-related material, Israel-related antisemitism, and incitement to violence—which we list separately because of its seriousness.

Traditional antisemitism includes conspiracy theories and tropes like “Jews are rich,” “Jews are dirty,” “Jews are evil.” And within the Israel-related category, more than half of the content is what we call the “transference” subcategory—where traditional antisemitic tropes are applied to Israel instead of Jews.

So instead of saying “Jews control the government in Australia,” people say “Israel controls the government.” Or “Zionists control the media.” The substance is the same; it’s just being redirected at Israel or Zionism. It’s a linguistic substitution—but the underlying antisemitic idea remains unchanged. And we’re seeing that kind of material spike dramatically.

Interestingly, different platforms exhibit different types of antisemitism. On LinkedIn, for example, one of the highest categories is Holocaust inversion—comparing Israel to Nazi Germany.

ZB: Really? LinkedIn?

AO: Yes. On TikTok, by contrast, that type of content is usually moderated out very quickly. It doesn’t gain traction. So it really comes down to what each platform recognises as antisemitism and how aggressively they enforce their policies.

ZB: LinkedIn’s a funny one. I actually found you through LinkedIn, and I’ve connected with a lot of really interesting people there. And it seems to have become much more active—especially since COVID, I think I read somewhere that its growth has outpaced other platforms.

AO: Yes. I believe the change started just before COVID, but the key point is that LinkedIn used to be independent. Then it was acquired by Microsoft. You don’t see much Microsoft branding on the platform, but they own it.

Historically, Microsoft stayed out of the internet space. After the US government’s antitrust case over Internet Explorer being bundled with Windows, they became very cautious. The court had threatened to break Microsoft up as a company.

So for a long time, Microsoft stayed away from social media. LinkedIn was their way back in. And once they took over, they began pushing this “bring your whole, authentic self” narrative. That encouraged people to post not just work-related content, but also political views, causes, and identity-driven posts.

Since October 7, we’ve seen a huge increase in political advocacy on LinkedIn. The platform has shifted quite dramatically.

ZB: Yes, I’ve definitely used it in that way myself. But I’m concerned—doesn’t it seem relatively easy to make a fake account on LinkedIn? They often look like legitimate people. You see someone named Sally who worked at this company, but it all looks a bit suspicious.

AO: Yes, that happens across all platforms. I’ve had multiple fake accounts created under my name—particularly on Facebook. I’m sure you’ve seen those messages from friends saying, “If you’re already my friend and get another request from me, don’t accept—it’s not me.” That’s usually scammers.

Platforms do have a major problem with fake accounts. Some are bots. Others are sock puppets—accounts people create just to troll, abuse, or spread misinformation, with no concern about getting banned.

I testified at a European Parliament hearing alongside other experts. When it was the platforms’ turn to speak, a Canadian MP asked the representative from X, “How many users do you have?” She gave the number. Then he asked, “How many of them are real people?” Her answer was, “I’ll have to get back to you on that.”

The proliferation of fake and duplicate accounts is huge. That’s a problem not just for users, but also for advertisers. They’re paying to show ads to real people—but the platforms are inflating their numbers by counting bots.

ZB: So, do you think users should have to verify their identity?

AO: Well, it depends on what you mean by “verify”. If you mean linking accounts to your real identity—like through government-issued ID—there are a lot of challenges there. I’ve worked on digital identity systems for a foreign government, and it’s complicated. There are also privacy concerns. If your social media account is directly tied to your government ID, that could link your posts to your tax records, your medical history—there are serious risks in that level of integration.

On the other hand, verifying that a person is real and unique—without necessarily knowing who they are—that should be possible. Many platforms already do it through phone numbers. Most people only have one, maybe two. And if the platform requires periodic verification via SMS, it helps ensure the person behind the account is real.

ZB: Could you do that in Australia?

AO: Yes. In Australia, when you get a new SIM card, you have to provide government ID. So the number is already linked to a real identity. Platforms wouldn’t necessarily have that information—but they could verify that your number is valid and uniquely yours. So if you’re using that phone number to verify your account, and the platform later needs to pursue an issue, there’s a trail that law enforcement can follow—if necessary—without the platform needing to know everything about you.

ZB: That makes sense. Although, you can still create multiple Instagram accounts and use them to harass whoever you like. Are there actually any consequences for that? I’ve heard of an anti-Israel account called “Don’t Be Like Bob.” Are you familiar with it? I’ve heard there are police investigations into who’s behind it, and that it may be run by multiple people.

AO: Yes, I am aware of it.

Recently, the Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism—Jillian Segal—released a national plan to address antisemitism in Australia. One of the things she called for was greater police resourcing so they can unmask anonymous accounts.

Police do have the ability to do this, but it requires a lot of time and technical effort. So they’ll only do it in the most serious cases. If someone’s receiving death threats or if there’s terrorist content, yes—they’ll pursue it. But for general online hate, they simply don’t have the capacity.

It’s a matter of proportionality. The Haddad case took years to work through the courts. Was it worth it? I would say yes, because it set a clear legal line about what is and isn’t acceptable. It wasn’t about Haddad personally—it was about clarifying public expectations and legal standards.

So, in the same way, we shouldn’t expect police to pursue every anonymous troll. But we do need them to act in the most serious or precedent-setting cases.

ZB: Do you have any tips for verifying images? I often use Google reverse image search or TinEye. Are those the best tools available to civilians?

AO: Yes—Google and TinEye are both very effective for reverse image searches. There are other tools, but those are the ones we use most often.

They do have certain limitations or guardrails. It will find matches for images, but it won’t identify individual people. That used to be easier to do, but now they’ve dialled it back, presumably for privacy reasons.

There are some other platforms that don’t have those restrictions—but we usually stick with Google or TinEye. They’re reliable.

Let me give you an example. Sometimes we receive screenshots of death threats with a profile picture and a generic username. All we have is that image and the abusive message. If the image is artwork or a stock photo, we can usually trace it. But if it’s a real photo of a person, we might not find anything. And even then, it’s worth being cautious.

Sometimes the photo belongs to a completely innocent person whose image has been stolen and used to create a fake account. You don’t want to wrongly accuse someone based on a profile photo that was used without their consent.

ZB: Yeah, I’ve actually experienced that. In high school, people stole images from my Facebook and created a fake Tumblr account pretending to be me—posting all sorts of horrible things. It’s been happening for a while.

AO: Yes, I’ve had similar experiences—both personally and professionally.

Someone once created a fake account impersonating the Online Hate Prevention Institute. They used that account to abuse people and then claimed we were behind it, saying things like, “We’re the anti-hate organisation—so we’re allowed to say what we like.” It was very damaging.

Thankfully, we have relationships with the platforms. When something like that happens to us, we can escalate it directly to them. In fact, I last spoke to Meta less than four hours ago. Part of that conversation was about a major incident currently affecting a women-run Australian charity called Collective Shout.

They recently ran a campaign that led to the removal of hundreds of online games that promoted child sexual exploitation and rape. One of the games they reported was deemed outright illegal by the classification board—no rating, just banned.

Since then, Collective Shout has been inundated with abuse. They’ve received death threats, rape threats, and threats of being doxxed. All because they got these games removed.

This is happening right now. And in serious cases like this, we step in—we gather evidence, we escalate it to the platforms, and we push for a rapid response. Because people’s safety is genuinely at risk.

ZB: That’s terrifying.

So, can people report things directly to the Online Hate Prevention Institute?

AO: They can, and people do. But we don’t have a public help desk for everyday reports—we simply don’t have the resources. We’re a small charity, funded mainly through public donations. We don’t receive the million-dollar grants that some other organisations do.

ZB: I saw that you have a guide on your website about how to report hate on the different platforms.

AO: Yes, we do. That guide helps people report content directly to the platforms. But in the most extreme cases—like terrorist content or serious threats—people do get in touch, and we do intervene.

It works the other way as well. Sometimes anti-hate accounts are falsely reported and taken down. We’ve helped get several of those reinstated. For instance, someone might post a screenshot of a Nazi symbol and say, “Please report this account,” but the platform’s AI interprets the image as hate speech and takes down the anti-hate account. We can step in and explain the context, and usually that gets resolved.

ZB: Yes, Quillette runs into these issues all the time. I actually feel like we’re shadow-banned on Facebook because of a post we made about erotic fiction. It included a tasteful image—like something you’d find on Unsplash or Shutterstock—but ever since, we’ve had drastically reduced reach. It feels like we were flagged as adult content. It’s been a learning curve.

And on YouTube, I’ve learned that even showing an image of the Twin Towers on 9/11 will get your video demonetised. Meanwhile, people are saying all kinds of extreme things on that platform with no issue.

AO: That’s probably an automated moderation policy aimed at stopping 9/11 conspiracy theories. There’s a lot of that content on YouTube, and most of it is antisemitic.

ZB: Yes, that makes sense. But the irony is that we talk a lot about antisemitism, the Holocaust, Nazism—and just by mentioning those topics on YouTube, we’re at risk of being flagged.

AO: Again, it’s about learning how to navigate within the rules. But frankly, I think it’s a good thing that they’re picking it up, even if imperfectly.

If you’re designing AI to detect images of planes flying into the Twin Towers—and 99 percent of the time that content is part of conspiracy theories—then yes, you’re going to end up catching the one percent of legitimate content as well. It’s not easy to distinguish the two.

ZB: Well, Andre, is there anything else you’d like to discuss today?

AO: Just that we’re incredibly busy at the moment. Online hate is on the rise, and society is becoming more fractured. So I’ll finish by encouraging people: be kind to each other. If you see hate online and it’s safe to speak up, then speak up. If it’s not safe, report it to the platform anyway—even if you think it will be ignored.

Having the report logged still matters. It helps create a record. And the more we do that, the more likely we are to get meaningful change.

ZB: Great advice. Thank you so much for the important work you do.

AO: Thank you for having me.