Tech

How Alex Karp Defeated European Defeatism

Alex Karp and Nicholas Zamiska have written a book about how the US can regain its technological and military edge. But The Technological Republic is really about something deeper: how America inherited Europe’s post-World War II trauma and turned it into a philosophy of defeat.

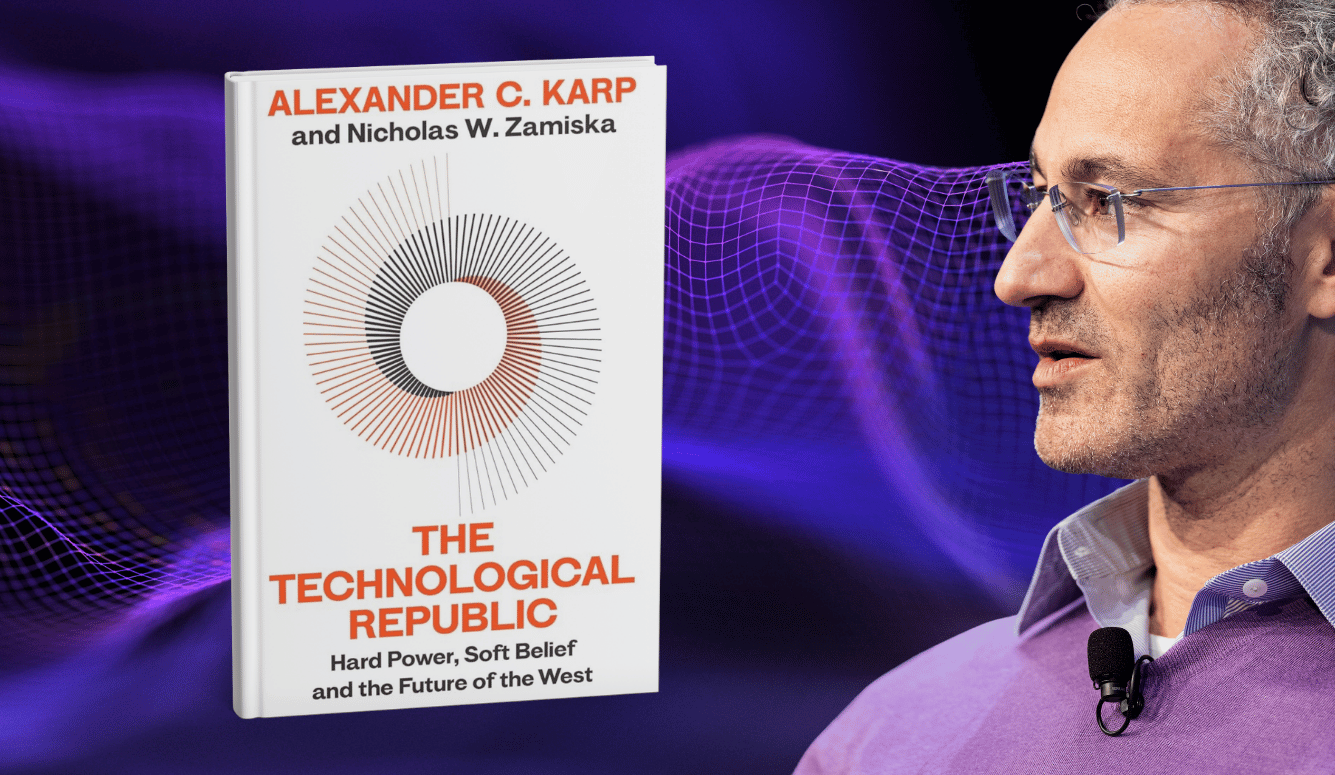

A Review of The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West by Alexander C. Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska; 320 pages; Crown Currency (Feb 2025).

War presents impossible ethical dilemmas: we don’t want to see people killed, but we must stop others from killing us; we don’t want to send our sons into harm’s way, but we do want to defend our homeland. The best solution is to make warfare more efficient and precisely targeted, thereby putting fewer humans at risk. This is exactly what companies like Palantir are trying to do. But the fundamental question remains: What are the correct motivations for waging war? This new book thinks it’s courage, nationalism, artistic taste, and a 95-year-old German philosopher called Jürgen Habermas.

Karp and Zamiska’s central thesis is that America made a catastrophic intellectual error after World War II. The country imported first-generation Critical Theory—a philosophy developed by traumatised Europeans like Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer who were trying to make sense of unprecedented destruction. This was a “manual for living with defeat” created by a continent that had just been carpet-bombed and overrun by invaders.

Critical Theory emerged from Europe’s desperate need for a psychological defence system after losing tens of millions of lives. It represented a politics not of defence but of defensiveness. The theory treats excellence, ambition, openness, and technological innovation as inherently suspicious—even murderous by default. This made perfect sense for a devastated continent seeking to minimise future losses rather than maximise gains.

Karp and Zamiska ask: Why did victorious America, in the middle of an economic and demographic boom, adopt this defeated mindset as the philosophy of its elites? America had experienced no Auschwitz, no Dresden, no Stalingrad—the very traumas that spurred the development of Critical Theory. Yet this European framework for processing collective defeat somehow became the default worldview in American universities, where future leaders were being educated.

The resulting ideology gradually changed America’s self-image. Universities began teaching that American strength is evil. Media workers educated at these institutions expressed these intuitions in their outlets. The trauma of the Vietnam War, academic careerism, and the self-victimisation epidemics that characterised the woke era only accelerated this trend. In their attempts to stay out of the culture war, the tech leaders of the past twenty years didn’t even frame their companies as American, focusing instead on egalitarian and relativistic globalism while America’s enemies were busy building military capabilities. Consumer-tech-era Silicon Valley turned away from projects of national importance entirely to focus on fun apps and handheld escapism. While Washington hired DEI consultants, Beijing and Moscow built drone armies. America essentially began training itself for a completely preventable future defeat, which Karp and Zamiska are now urging us to prevent.

The Technological Republic was originally conceived as a warning for the Biden administration. It argues that America’s tech leaders need to wake up from their postwar European nap: what Karp and Zamiska call “the winner’s fallacy” is the comfortable assumption that faceless public servants can be entrusted with national security while entrepreneurs build gambling apps and chase YouTube followers—an assumption that to the authors seems dangerously naive. Instead, they argue, Silicon Valley should focus on making America and its allies stronger through advanced military and intelligence technology. The developments that followed the second Trump victory suggest that people were listening to Karp even before the publication of this book. The reader is always left a few steps behind—perhaps intentionally.

Karp’s unusual academic background makes him uniquely qualified to diagnose this problem. His trajectory is very similar to my own. Like me, Karp studied continental philosophy in Central Europe before becoming a tech entrepreneur in America. He studied the intellectual tradition that produced Critical Theory, writing his PhD on the second-generation thinker Jürgen Habermas. Habermas’s theories are far less defeatist than those of his post-WWII mentors were, but for this reason his school of thought has also been less seductive to Americans—until now. Unlike his Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel, who has famously moved toward right-wing solutions to America’s sovereignty problems, drawn from the works of such thinkers as the legal theorist Carl Schmitt, Karp draws on Habermas’s left-wing vision of an ideal public sphere and advocates meritocracy and cooperation. He believes technology is inherently rational and, to Karp, rational equals morally good.

In the book’s final chapter, “An Aesthetic Point of View,” the authors argue that modern, founder-led companies are not just a geopolitical necessity but an exercise in aesthetics, an act of artistic creation. America, the authors write, has lost its collective identity and that is reflected in the lack of an artistic vision, which Karp and Zamiska see as both symptom and cause of the nation’s strategic weakness. They lament the shortage of heroic contemporary art, which could inspire and chronicle great national projects. “Our collective and contemporary fear of making claims about truth, beauty, the good life, and indeed justice have led us to the embrace of a thin version of collective identity, one that is incapable of providing meaningful direction to the human experience,” they write.

This helps explain why the “tech Right” has become obsessed with classical architecture and great art at the same time as it rediscovered its military aspirations—why Musk’s algorithms push Turner landscapes and Bernini buttocks onto your X timeline, and why the venture capital firm a16z has suddenly changed its logo to Art Deco. Beauty, Karp and Zamiska argue, can unite us in a way mere political argument cannot. Where language, with all its ambivalence, fails to fully express the truth, a piece of art might represent us all. This is a viewpoint drawn from continental philosophy, which frequently asserts that art is a type of synthesis: beauty is both exceptional and collective. Without a shared aesthetic vision, it becomes harder to mobilise people to undertake ambitious collective projects. Founders, for the authors, aren’t just business leaders—they’re artists creating the future.

Contemporary American politics is an exercise in staving off nihilism. Some pursue meaning through traditionalism: a return to God, or to traditional sex roles, expressed through faux-nostalgic social media posts that feature women gathering fresh eggs while wearing low-cut dresses. Karp and Zamiska present an alternative way of finding meaning: by embracing the abundance agenda of technological progress. Making new things, creating new industries, inventing the future, and ensuring there is more for everyone: this is their antidote to isolationism and defeat.

Karp and his Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel represent something unusual in Silicon Valley: Americans who understand European culture, which is still steeped in post-war anxieties. This perspective helps them grasp how the West’s confidence and self-image have evolved—and how these European philosophical traditions continue to shape people’s choices today.

But there is a way, Karp and Zamiska argue, to break free of the defeatist tradition, though the challenge in doing so will be immense. The techno-optimists are up against sprawling bureaucracies, sclerotic traditions, and risk-averse citizens. There is a limit to how much even an exceptionally dynamic individual like Karp can accomplish in the face of institutional inertia. Yet the alternative is unacceptable. Our primary goal, they argue, should be the prevention of war, yet that is only going to be possible through effective deterrence, even if we risk accelerating the arms race. They quote John Foster Dulles: “The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art.”

Karp and Zamiska’s ultimate message is that America needs to remember how to win and they argue that winning, in this case, is morally good. That means rejecting the philosophy of defeat the country borrowed from traumatised Europe and embracing the technological ambitions that made it a superpower in the first place. The alternative is watching China and Russia shape the future while American elites debate their own moral inadequacy. We wanted a backstage glimpse into what drives America’s military innovators, and we got it.