Yoga

Ancient Indian Tradition—Or Twentieth-Century European Export?

Evidence suggests that today’s common yoga practices were inspired by a popular 1924 Danish gymnastics manual.

Our contemporary physical yoga practice has often been sold as a 5,000-year-old Indian tradition—unspoilt and unbroken. That it might be otherwise would hardly have occurred to me when, in early 1999, I travelled to India and searched for a guru.

I’d just quit a job as a management consultant in Germany to spend the winter in Goa, a former Portuguese colony (as the enduring names of places and people attest) that now comprises the smallest of the Indian federal states. I began the winter at the guest house of the De Souza family in a seaside town called Baga, before moving on to Vagator, a village with pristine beaches. Hippies had long been drawn to this area, where their culture was merging with an emerging techno scene.

“Is there a place where I can take some yoga lessons?” I asked the lady at the corner store, which I relied upon for email, snacks, and bottled water. I’d trained in karate, and still made occasional use of the stretches.

“There’s a guy at Anjuna Beach,” she said. “I believe he comes from Germany.”

I swallowed my disappointment that my first yoga teacher would not be Indian, climbed onto my scooter, and whizzed off.

When I got to the beach, the blistering heat of noon was giving way to the warm colours of the late afternoon. A little way inland, the red earth of a palm grove had been flattened and carefully cleared of branches and fallen leaves. The sound of the Arabian Sea was audible in the distance.

A dozen suntanned bodies, perfectly toned, were gliding from posture to posture. The yoga teacher, a sinewy man in a loin cloth with the sunken eyes of a fakir, seemed to have sprung straight out of a picture book. He was teaching without using words. Instead, he glided from one student to the next, adjusting their positions with his hands. I’d seen few things so beautiful in my life.

The lesson ended, and the students silently dispersed through the palm trees. The teacher told me that the yoga he taught was called Ashtanga. In this style, the student practises a fixed series of bodily postures—or asanas—guided by the count of her breath. His silent style of teaching, he said, originated in Mysore, a city in the southern part of India. There, his famed guru, K. Pattabhi Jois (1915–2009), called guruji by his affectionate disciples, was then still teaching yoga in the traditional way.

“How does one learn?” I asked.

“Just give it a try,” he replied enthusiastically. “Guruji always says, ‘Yoga is 99 percent practice and one percent theory.’”

Twenty-four hours later, I found myself spread-eagled on my first yoga mat, then still made of bamboo. As we got toward the end, the pushup-style vinyasas—transition movements that link one asana to the next—had almost been too much for my weary arms. But my teacher was encouraging. “You’re a natural,” he told me. “Come back tomorrow.”

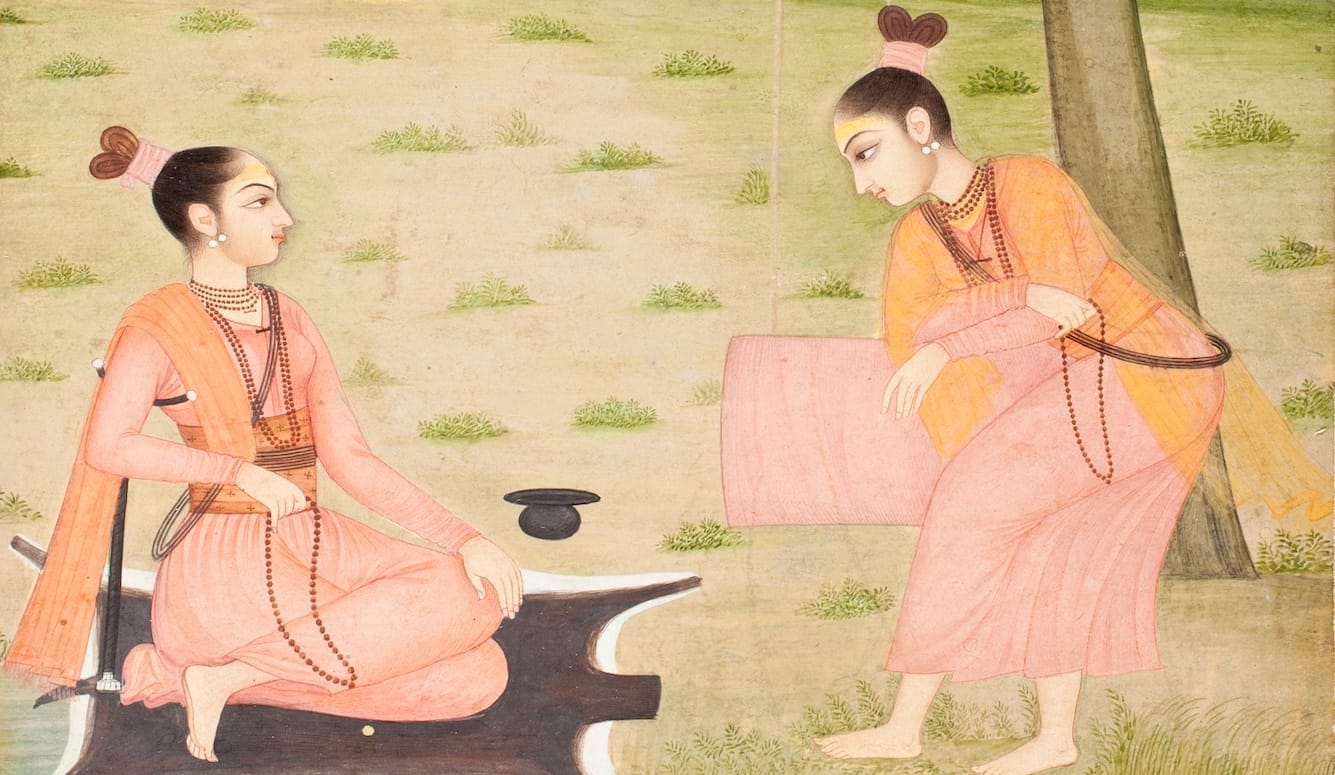

I asked who’d invented all this. The teacher—whose name, I learned was Rolf Naujokat (1954–2024)—told me that Jois, when asked this question, always replied that he’d “never changed anything,” and was simply imparting knowledge provided by his own teacher, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989). Krishnamacharya, in turn, would point to his own guide, Ramamohan Brahmachari—an ascetic who, he claimed, lived in a Himalayan cave, where (it was rumoured), he’d mastered 7,000 asanas.

For his part, Brahmachari reportedly said that he was merely passing on what had been written down in the Yoga Korunta, a manuscript he claimed to have discovered in a place he vaguely called the “Library of Calcutta.” Krishnamacharya had viewed the manuscript and passed a transcript on to Jois—in whose care, alas, it was eaten by ants.

In retrospect, it seems remarkable that I took such a story at face value. Two decades previously, Edward Said had published his classic book, Orientalism, concerning the West’s misconceptions of the East. It seemed that I still wanted to see my prejudices of India confirmed. At the time, every puddle of water in a gutter seemed to reflect the jewels of the Nizam of Hyderabad and the towers of the Taj Mahal.

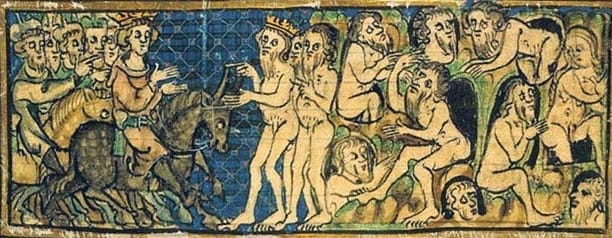

When Alexander the Great crossed the river Indus and invaded the Punjab, he soon fell into conflict with the gymnosophists—“naked sages” who’d acquired a reputation for concise servings of wisdom. When they refused to pay tribute to this foreign king, and demanded that he came to them instead, Alexander instructed one of his helmsmen—a man named Onesicritus, who was also something of a philosopher—to find out what the renunciates were all about.

I came across this story in Alistair Shearer’s 2020 book The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West, which I read during the COVID lockdown. The original Sanskrit term, I learned, can be translated as “to yoke” or “to unite.” Over time, the word became an umbrella descriptor for physical and spiritual practices that people have created to connect with something bigger than themselves.

I started to delve deeper into yoga’s roots, maybe because I was thrilled by the feeling that my personal encounter at Anjuna Beach was part of a long historical chain.

The most elaborate description of the gymosophists that I found was in the Geographica of Strabo, a Hellenistic historian who lived in Alexandria around the time of Christ. I’d studied Latin and classical Greek at school and it brought to mind what I’d learned at school in Switzerland, where a teacher had made me translate some of Strabo’s writings.

Onesicritus, I learned, was a Stoic, who believed that a virtuous life can be achieved through training (in classical Greek, askesis), just as an athlete can train for the Olympics. And he’d heard that the gymnosophists were practising the art of endurance. Outside a city called Taxila, on the eastern shore of the Indus, he encountered “fifteen men, naked, in the most different positions—standing, sitting, lying—immobile until the night; then they returned to town. At noon, the heat of the sun was so unbearable that almost nobody (with the exception of them) could touch the ground with bare feet.”

Strabo’s description evoked images of sadhus, the holy men of Hinduism and Jainism—spiritual progenitors of the yoga to which I’d now became devoted. Sadhus are archaic, sometimes even aggressive characters with dreadlocks who paint their body with ash; many still practise austere endurance exercises, which they call tapas. There are sadhus who live on a single leg. There are sadhus who’ve been extending one arm outward for so long that it has started to wither. There are sadhus who move only by rolling over the earth. And there are sadhus who have hands encased by cages fashioned from their uncut fingernails. It made sense for me to assume that there might be little difference between the sadhus of today and the gymnosophists encountered by Alexander the Great.

There was one particular man called Kalanos dozing on a rock, who harshly asked Onesicritus to undress before speaking. And there was another, called Mandanis, who said, “the best philosophy is the philosophy that liberates the soul from lust and suffering. Suffering and pain are not the same. You align the body toward pain so that the mental faculties increase.”

The word “yoga” does not appear in Strabo’s Geographica or in any other Hellenistic text. It appears much earlier, in the Vedas, a collection of religious texts with origins dating back to the second millennium BC. The definition that is most popular today, however, can be found in the Yoga Sutras, written down by a sage called Patanjali somewhere between the fourth century BC and the second century AD: “Yoga is the state of the cessation of mental turbulences.”

The Yoga Sutras begin with a collection of ethical rules, go on to describe the experience of meditation, and finish with a list of supernatural powers that a yogi (one who has mastered the art of yoga) can attain through various means, including the use of herbs. (Parallels to shamanic voyages are obvious, although the literature I know does not draw them.) The yogi will be able to transcend time and space, travel to hidden realms, and enter other people’s minds.

The “seat” (or way of sitting) that the yogi assumes—such is the original meaning of the word asana in Sanskrit—should be “light and firm.” But gymnastic postures, as we understand the term asana today, are not mentioned in the Yoga Sutras.

Sutras are aphorisms, so concise that unravelling their meaning requires additional commentary. Translations of the Yoga Sutras differ, and nothing is known about their author.

The era to which we attribute the creation of the Yoga Sutras coincides with the emergence of syncretistic kingdoms in the Punjab following the reign of Alexander the Great. One of these was the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, which was succeeded by the Indian-Greek kingdom, which was swallowed by the Kushan Empire. The latter was established by nomadic tribes from China and is credited with bringing Buddhism to the region.

Today, however, nobody knows which philosopher or sage travelled where, and who sat with whom underneath which banyan tree. The old gardens, libraries, and palaces have long since disappeared amid the dust storms of Asia. Only a handful of fragments and coins survive—included some excavated outside the ruins of the aforementioned Taxila, in contemporary Pakistan.

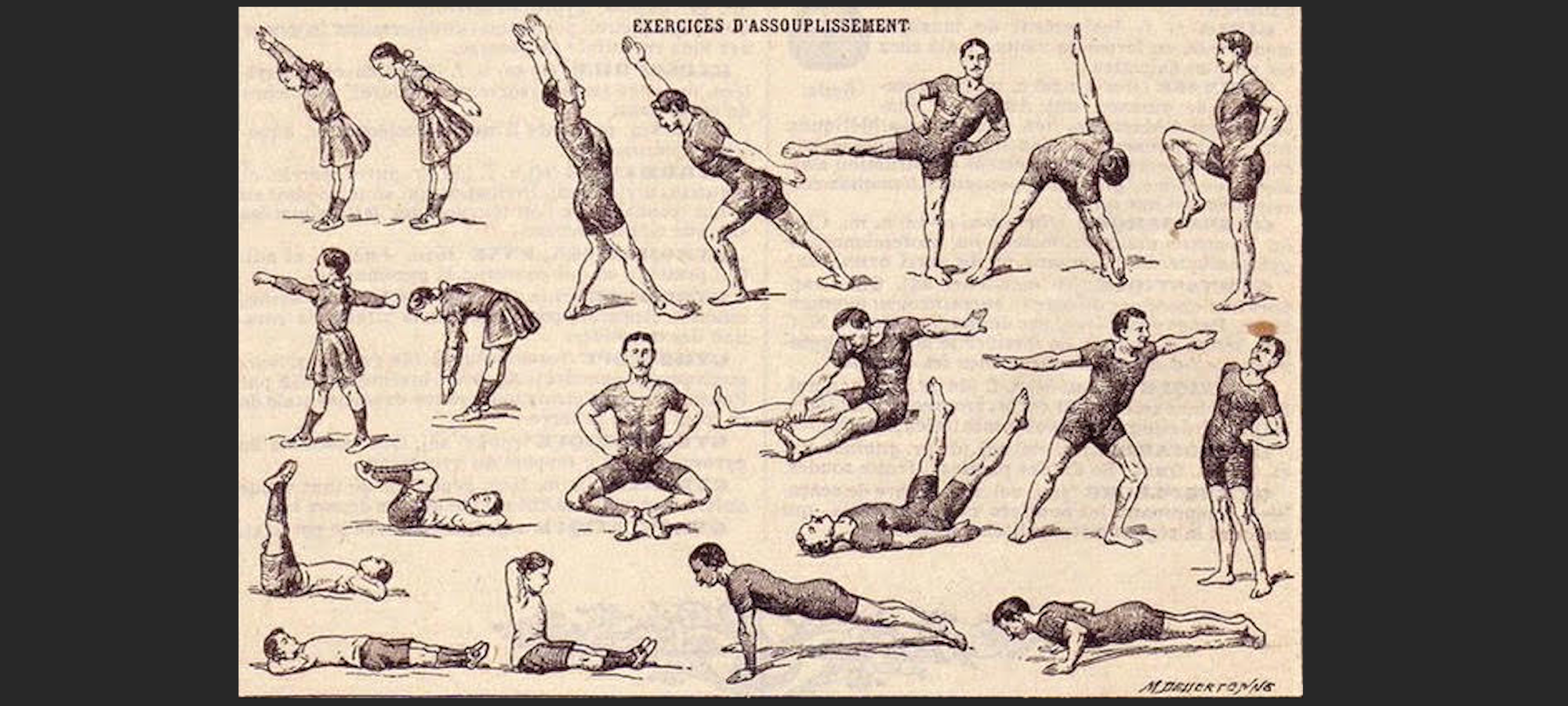

This brings me back to the Yoga Korunta, that ancient manuscript supposedly eaten by ants. My belief in its existence had already been shaken a few years into the new millennium, when the film director Frauke Finsterwalder, knowing of my interests, sent me what seemed to be a vintage French gymnastics poster from the Belle Époque. Underneath the headline, Exercises d’Assouplissement (Flexibility Exercises), a gentleman with a moustache in the style of Marcel Proust assumed a series of calisthenic postures. Their similarity to my yoga practice was striking, and remained embedded in my mind when I returned to India in January 2020 to deepen my yoga studies—just as a hitherto unknown virus was spreading beyond the Chinese city of Wuhan.

I started my trip in Rishikesh, a small city in northern India, on the southern edge of the Himalayas, where I spent a week at an ashram. Even here, in the self-proclaimed “world capital of yoga,” the services on offer seemed oriented toward an almost exclusively Western audience. When a new cohort of sturdy Canadian housewives flooded the place, assuming pious expressions and hugging each other silently in spiritually styled clothing, I decided it was time for a hike.

A guide took me up countless stairs to watch the sun rise at a local temple. Halfway down the descent, he led me and the other guest, a Brazilian woman in thongs, onto what he described as a shortcut to a waterfall. After stumbling down a ravine, he managed to get thoroughly lost.

“Are you lost?” the Brazilian asked sharply.

“No, no, no,” the guide replied airily.

“He is not telling the truth,” my companion whispered to me.

Half an hour later, we found ourselves crawling on all fours through the undergrowth of a canyon, branches lashing at our faces. Wherever we were, it was a place without cellphone service. In this moment of despair, I heard the voice of Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), an Indian spiritualist patronised by Western sponsors, who was a firm opponent of organised religion: “Truth is a pathless land.”

In that moment, the idea that yoga and its associated spiritual beliefs pointed at some important truth about the universe suddenly seemed preposterous to me. All at once, it suddenly occurred to me that the Brazilian lady and I—everyone at the ashram, in fact—were victims of some giant scam, in which our incompetent tour guide played only a bit part.

Even when we had miraculously found the road, my spirits refused to be lifted. By the time I’d moved on to Goa, my doubts had arrived with me.

Rolf Naujokat, the old German at Anjuna Beach, was still giving lessons, but he was away travelling. Frauke, who’d sent me a copy of those Exercises d’Assouplissement, now lived with her husband, the writer Christian Kracht, in the foothills of the Himalayas. Christian, an old friend of mine, introduced me by email to his 87-year-old American neighbour Sally, who’d moved to Goa for the winter, because he believed we shared some eccentricities.

Sally had been married to Wynn Chamberlain (1927–2014), a painter who frequented Andy Warhol’s Factory. She still owned a Moroccan djellaba given to her by famed beat poet William S. Burroughs. In the 1970s, Chamberlain burned his paintings and brought Sally (née Sally Stokes) and their children to India, where they lived in a mud hut for a time and searched for a guru. They found a hermit who could cast spells and enter people’s minds—until, alas, he lost these supernatural powers on the eve of his wedding.

On a humid night in February, I had dinner with Sally (who passed away in April, 2025) beneath the paper lanterns of a fusion restaurant on the road to Anjuna. We were joined by her daughter and son-in-law, a professor of Sanskrit.

To general merriment, I narrated the tale of my Himalayan misfortunes. While holding forth in a caustic tone, I showed them the Exercises d’Assouplissement image on my phone. “That’s what we call yoga,” I said.

Between mouthfuls, the professor recommended a 2010 book tracing yoga’s modern iterations—Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice, by the scholar Mark Singleton.

Back at my hotel, a creek-side yoga retreat situated between Mandrem and Arambol, I crossed the suspension bridge that led to my hut, and noticed a row of new buildings at the other end of the shore. One was in the style of a Moroccan palace, the next a Swiss chalet—and so on. A cranked-up sound system entertained Russian package tourists with synthesiser pop. Public services hadn’t been able to keep up with local growth, and so garbage had simply been emptied into the ditch. Apart from the sky above, there was nothing here to remind me of the barely developed Goa of semi-legal rave parties I’d encountered almost a quarter century previously. Clearly, it was time to return to Berlin.

Within days, the world would go into lockdown, giving me ample time to start my research in earnest.

Mark Singleton was part of the Hatha Yoga Project (2015-2020) at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies. Operated in conjuction with the École Francaise d’Extrême-Orient in the former French colonial stronghold of Pondicherry, the EU-funded venture aimed to discover the origins of our contemporary physical yoga practice through fieldwork and the study of ancient texts.

In Yoga Body, the book that had been recommended to me, Singleton presents convincing evidence that modern yoga postures (of the type that bewitched me at Anjuna Beach) weren’t exclusively Indian in origin, but rather had been developed through a modern exchange of ideas spanning east and west.

The term “Hatha yoga,” which dates to the Middle Ages, refers to any type of yoga that uses physical movements to channel energy and improve human wellbeing. Historically, such movements were often associated with occult fraternities, warrior ascetics, and would-be sorcerers. When India began to fall under British colonial rule in the eighteenth century, numerous mendicant monks roamed the country, sometimes heavily armed, giving the Hatha yoga tradition a bad name. They often congregated around holy sites, smoked drugs from a clay pipe called a chillum, sometimes extorted alms from the elderly, and frightened small children. Even their countrymen treated them as symbols of national backwardness. Patanjali’s teachings had been forgotten.

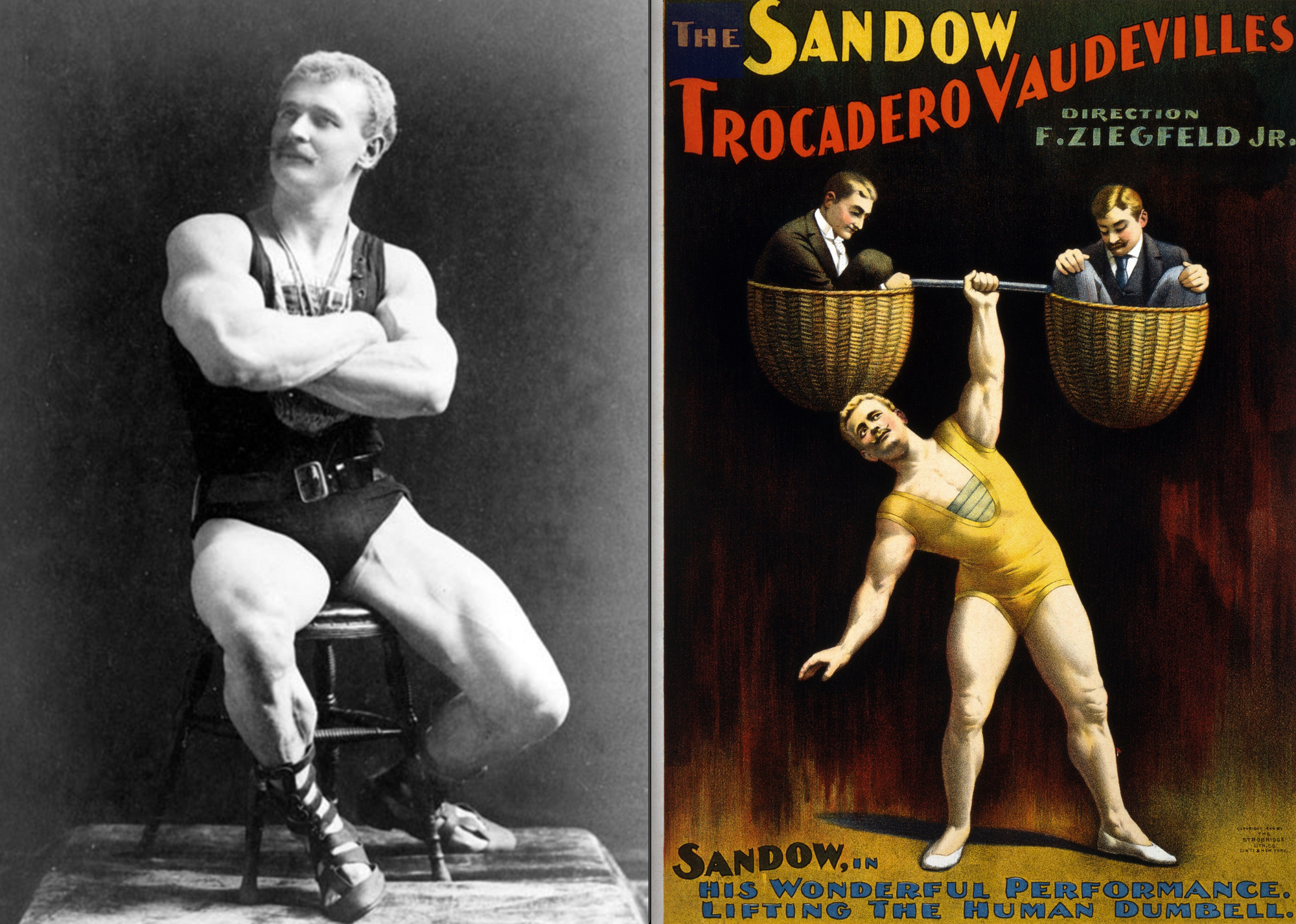

In a bizarre twist, it was a German Jewish bodybuilder who helped bring yoga back into fashion. In 1905, Eugen Sandow (1867–1925), born Friedrich Wilhelm Müller in the Prussian city of Königsberg, toured the far East, displaying his perfectly toned body to legions of awed onlookers. In India, where national self-esteem was still suffering a half century after the failed Rebellion of 1857, his tour started a fitness boom.

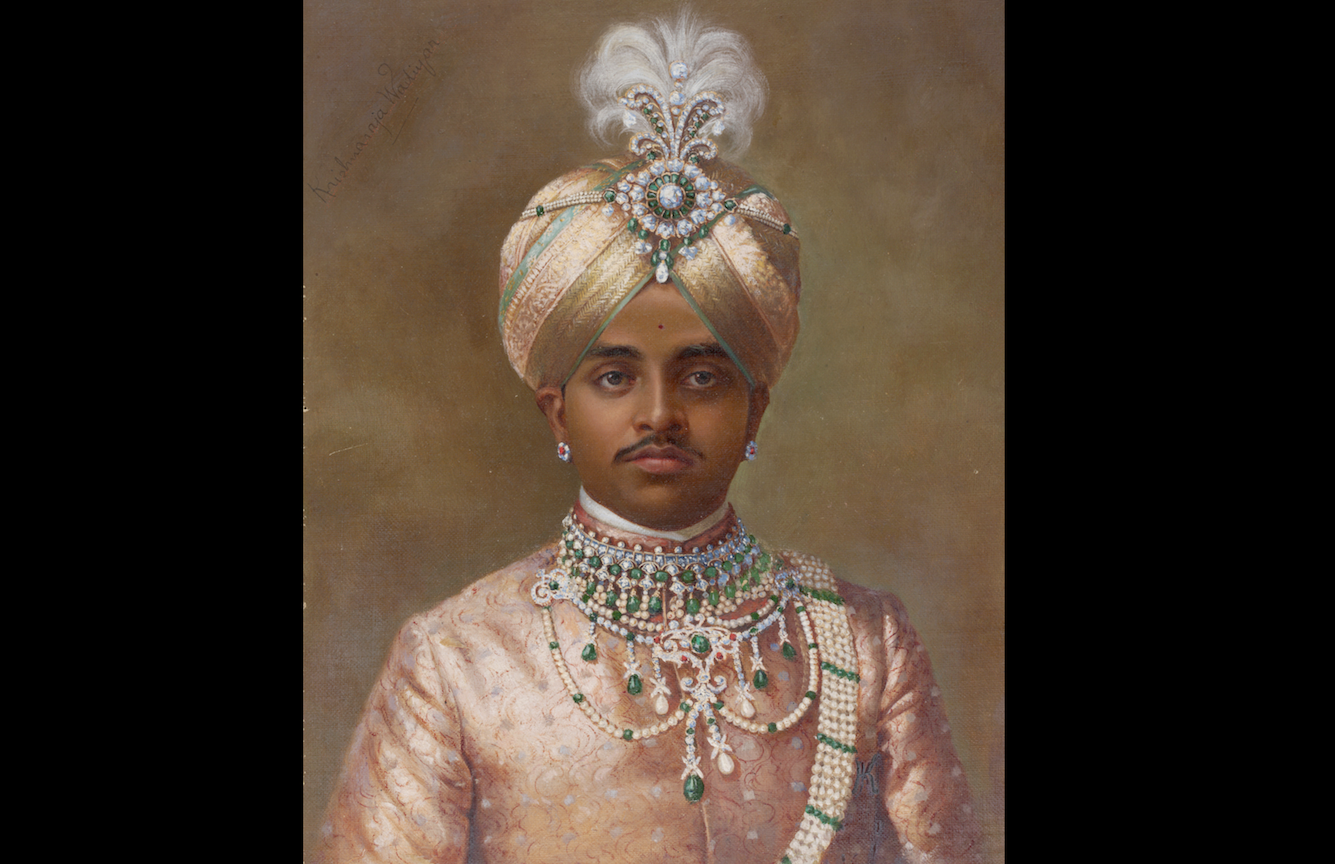

Sandow’s fitness methods influenced Indians such as K.V. Iyer (1897–1980), a gymnast and bodybuilder from Bangalore who would go on to become probably the most influential proponent of physical fitness in India during the first half of the twentieth century. Iyer and other like-minded fitness gurus (as we might now call them) began taking a fresh look at the asanas associated with the (by now disreputable) Hatha yoga tradition, which they repackaged as a made-in-India alternative to imported British-inspired calisthenics. His sponsor was Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV (1884–1940), the fabulously wealthy Maharaja of Mysore. His Highness exhibited a fondness for public-reform campaigns, and anything involving sports.

In a side wing of Mysore Palace, one of Iyer’s pupils offered bodybuilding classes, which soon became hugely popular with the local jeunesse dorée. In the same wing, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, a member of a respected Brahmin family who’d recently been appointed as a fitness coach, took charge of an abandoned royal gym, where he began the task of establishing Hatha yoga as an indigenous alternative to Sandow’s methods.

And yes, this is the same Tirumalai Krishnamacharya whom my original beach yoga instructor back in Goa had identified as the teacher of his own teacher, K. Pattabhi Jois.

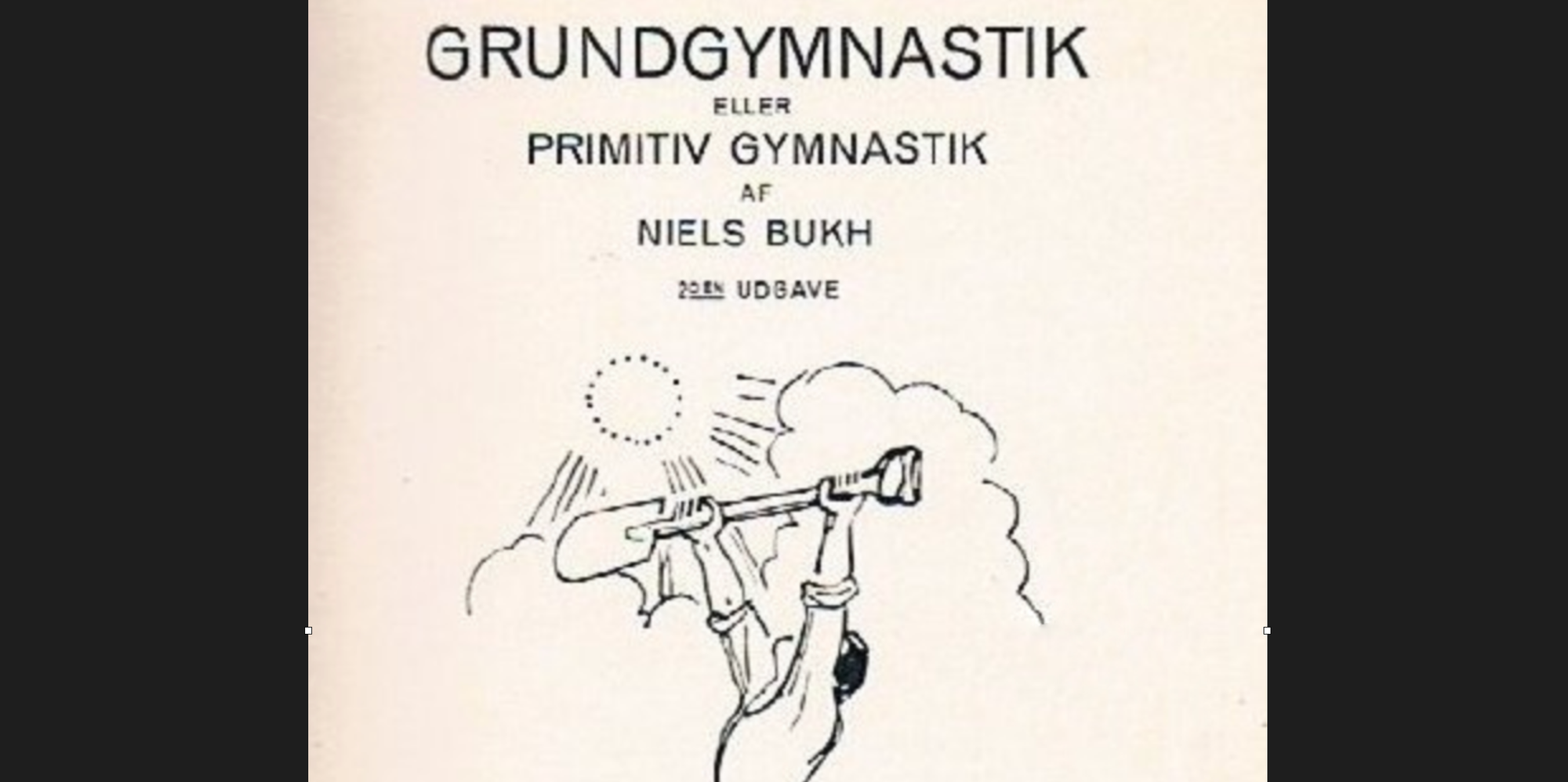

Krishnamacharya apparently had a gift for marketing. As if he ran a travelling circus, he would tour towns and villages, putting his star pupils on display. And while Hatha yoga still had a bad reputation, he seems to have spiced up his lesson plans with non-yogic traditions: In addition to emphasising sun salutations, which were already practised by Indian bodybuilders, he apparently co-opted a hugely popular exercise system developed by Niels Bukh (1880–1950), a Dane who ran an internationally acclaimed high school for gymnasts in the Danish town of Ollerup.

Bukh had been inspired by many European traditions, including that of French army officer Georges Hébert (1875–1957), whose Méthode Naturelle was based on the idea that the Indigenous peoples he’d observed in the Americas owed their athleticism to “nature as a fitness coach.”

In Bukh’s system of “primitive” or “primary” gymnastics—encoded in a widely translated 1924 book, Grundgymnastik eller primitiv gymnastik—disciples trained each other through mutual stretching exercises and rhythmic group performances. His male students were clad in skin-tight leggings (which left little to the imagination), and everybody moved in perfect symmetry, like modern synchronised swimmers, while a maestro figure waved his hand like a conductor’s baton.

In 1931, Bukh, who had a penchant for dressing in colonial whites and posing with his Great Danes, promoted his system on a worldwide tour. And his precepts would soon become part of the official fitness program of the British army, as well as of the YMCA, which played a crucial role in the establishment of sports in India. Back in 1857, the year of India’s failed uprising, the YMCA opened its first Asian branch in Calcutta; eighty years later, the Maharaja of Mysore would host its delegates for jubilee celebrations.

This is not new information. All of it can be found in the above-referenced books by Alistair Shearer and Mark Singleton, among other sources. But it was new to me, and it left me feeling somewhat betrayed.

To make matters worse, I learned that in 1933, the same year in which Tirumalai Krishnamacharya assumed his new job in the Mysore Palace, Bukh, the “Wizard of Ollerup,” openly declared his support for Adolf Hitler. Indeed, his attraction to Nazi ideology began even earlier: In the 1920s, Bukh had a Swastika inlaid in the floor of his Ollerup swimming pool.

The Nazis had a fetish for virility and physical strength; and sport was central to their racist efforts to breed an Aryan “master race.” Upon the invitation of Hans von Tschammer und Osten, the Reichssportführer (the Reich’s leader of sports), students from Ollerup presented their mass gymnastics spectacle as guests at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. The performance was given in the evening, after rain had begun falling. But the remaining spectators thunderously applauded Bukh’s efforts to transform the bodies of Danish farm hands into the statuesque ideal of “nordic” warriors and classical Greek gymnasts.

Although Ashtanga yoga had been developed for underage Brahmin boys living in a tropical climate, not for Europeans with bodies like my own, I’ve stayed loyal to Pattabhi Jois’ system. Its main attraction, for me, is that practitioners need not fixate on the demonstrations offered by a teacher at the front of the room, but are instead allowed to look inward. By following the pace of one’s own breath, what looks like a workout can easily turn into an act of physical meditation.

At the beginning of each class, we put our hands together in namaste, close our eyes, and chant a mantra:

Vande Gurunam Caranaravinde…

I pray to the Lotus feet of the Supreme Guru who teaches the good knowledge…

Respect for the teacher and the teacher’s lineage tends to lie at the core of Asiatic training regimens. And so a part of me still hoped that all this research had led me down an erroneous path. Unfortunately, further evidence tended to back up what I’d learned from Shearer and Singleton—including the 1938 movie Olympia by Leni Riefenstahl, which portrays the athletic German body in an almost religious light. I felt my chest tighten when, in the second part, I spotted three men who, from about the eight-minute mark onward, can be seen gliding into postures sold to me at Anjuna Beach as pashimottanasana, purvottanasana, navasana, or chakrasana.

On the basis of archival research, I was able to determine that the tricot with the number 134 was worn by Willi Stadel from Germany; tricot number 41 by Hikoroku Arimoto from Japan; and tricot number 122 by Kenny Griffin from the United States. All three were filmed for Olympia while competing in floor exercises that were part of the 1936 men’s Olympic gymnastics program. It is likely that their postures were influenced by Bukh, who had visited each country, and whose system had been adopted as an international standard through his bestselling exercise manual, Grundgymnastik.

I remembered the tale of the “Library of Calcutta,” and tried my luck with Google. And there it was: the English translation of the Grundgymnastik—Primary Gymnastics—in its 1939 edition, still available at the library of the University of Calcutta, filed under “Gymnastics,” and catalogued as b855 ed.5. The catalogue entry may not be as grand a discovery as the Yoga Korunta—though it suggests that Niels Bukh’s manual was available in India during Krishnamacharya’s era.

Since Calcutta was far away, I purchased an antiquarian copy online. In the black-and-white photographs, I saw men in black shorts stretching in pairs, in postures that evoked the adjustments I’d witnessed on Anjuna Beach, as well as adopting postures I’d formerly known as asanas. The prescribed work plans could have been a model for the fixed series of Ashtanga yoga.

To be clear: Singleton explicitly disavows the claim that Krishnamacharya borrowed directly from Niels Bukh. And some members of the yoga community will argue that there are only so many ways in which the human body can move; and that the asana concept is innate to the human physique, simply waiting to be discovered by different cultures.

To some extent, they have a point. Certainly, I agree that yoga is more than asana; that asana is more than Hatha yoga; and that Krishnamacharya did not rely exclusively on Niels Bukh. In any event, the essence of Ashtanga yoga isn’t the postures, but rather the union of breath and movement. Still, none of these truths serves to fully reverse the sense of shock I felt when I saw what I thought to be ancient Indian yoga exercises being performed by followers of a twentieth-century Danish fitness celebrity.

As lockdown dragged on, I contacted an old friend, Lara Baumann, who lived on Ibiza. Lara had trained with both Jois and Krishnamacharya’s most famous pupil, B.K.S. Iyengar (1918–2014). Like me, she’d heard rumours of the influence of British-army calisthenics on asanas. However, she’d never heard of Niels Bukh.

Then I mentioned the Yoga Korunta, the manuscript supposedly eaten by ants.

“I kept on telling Pattabhi Jois that the Yoga Korunta is complete nonsense,” Baumann said. My feeling of betrayal was compounded by the fact that the social rules contained in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali include satya, or truthfulness.

But I also began to find humour in all of this: This mysterious creed that drew legions of westerners to India—including me—actually traced some of its roots to physical fitness movements that had emerged in our own European backyard. The dominant theme here isn’t really eastern dishonesty, but rather western self-deception.

For her part, Lara told me that she was on Krishnamacharya’s side. “As the seat of a monarchy, Mysore has always been a conservative town, and it’s the job of the Brahmins to keep the old traditions going,” she said. “Krishnamacharya had been charged with developing something that gives people power, so he integrated the successful methods of the colonial rulers while also selling it to the Maharaja as a local product. In the end, it’s all a question of marketing.”

“India has always been a laboratory,” Lara continued. “They take what works for them. And Krishnamacharya was one of the first men to allow women access to yoga. Have you seen the movie Yogawoman?”

She was referencing a (very unkindly reviewed) 2011 documentary by Kate Clere, which shows how yoga, once the dominion of male renunciates, has, through one of its numerous historical metamorphoses, turned into a tool for (as she presents it) female emancipation. It should feel obvious to anyone who’s seen the movie that none of the women interviewed would allow a dead Danish fascist to take their inspiring practice away from them.

Eventually, the lockdowns ended, and people were allowed back into my yoga studio, which, for months, had been teaching only on Zoom. When I unrolled my mat, I was, once again, engulfed by the breath of my fellow Ashtangis, who now practised in socially distanced fashion underneath open windows.

I felt like the owner of some dirty secret, who might be ostracised from the entire yoga community if I communicated my research publicly. But as I lifted my arms for the first post-lockdown sun salutations, it dawned on me that it would be positively Eurocentric to assume that Krishnamacharya or Jois had been deliberately deceiving us.

I remembered a discussion I’d had, many years ago in New Zealand, with a Korean teacher of Ashtanga yoga. In his opinion, it was part of the Asian intellectual tradition to eschew personal credit for a discovery or creation, and to place it in a larger lineage. By channelling Brahmachari and the Yoga Korunta—whether in a historically correct fashion or not—Krishnamacharya had simply freed his creation from the narrow confines of a gym in Mysore and placed it in an epic historical context.

I realised that I was at risk of exhibiting the “Orientalism” that Edward Said once warned us all about—a belief that the Orient had to be radically different from the West. When it turned out that the exercises Krishnamacharya was teaching in Mysore could have been inspired by a 1924 Danish fitness manual, this belief came crashing down. But I was then in danger of succumbing to another distorted view of the Orient—an orient of “failed narratives” and “disordered chronicles,” where vendors peddle forged antiquities in front of ancient monuments.

As I see it now, the history of yoga simply needs to be told from a different perspective. During the colonial period, the east discovered the west at the same time that the west was discovering the east. And many of India’s best people found ways to adapt lessons from the foreign rulers to suit their local needs. Thus a gymnastic genius named Tirumalai Krishnamacharya trained the youth of Mysore Palace in a calisthenic synthesis that likely borrowed from Scandinavians—thereby transforming the bodies of colonialism’s victims during the struggle for Indian independence. That system turned out to be so effective that it became the basis for contemporary Hatha yoga.

So, imagine this: A Brahmin hurries through the courtyard of his house in Mysore. He calls for his wife, and produces a manual out of the folds of his dhoti, the traditional dress of his caste—whose cover is illustrated with the silhouetted images of European men thrusting their chests at the heavens.

He opens the book and randomly points at one of the illustrations. “I think,” he says—as his eyes begin to sparkle—“this can be useful to us.”

Even today, despite it all, I find myself nodding in silent agreement.

Elements of this article first appeared in the 22 August 2020 edition of the Swiss German-language publication DAS MAGAZIN.