India

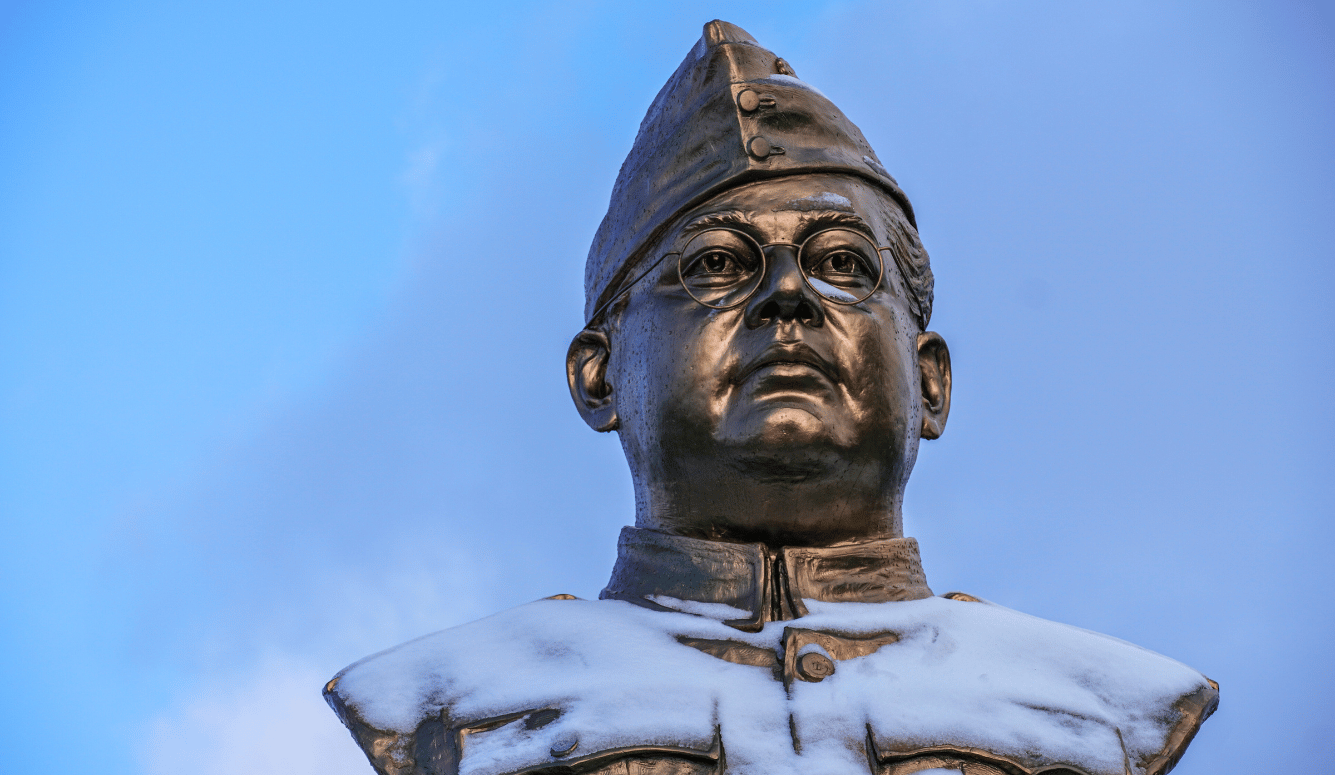

The Soldier and the Revolutionary

The contrasting lives and ambitions of two major figures in the fight for Indian Independence: Kodandera Subayya Thimayya (“Timmy”) and Subhas Chandra Bose.

Part One: Bose. India, 1897–1920s

The public life of Subhas Chandra Bose began with a scuffle in a Calcutta school corridor and a history teacher he transformed into a verb.

In 1897, while his parents celebrated the arrival of baby Subhas, the land that he would one day attempt to liberate marked the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria, Empress of India, with vast—and vastly expensive—public ceremony. At the same time officials struggled to provide relief to millions who were suffering and dying from severe food shortages. These were portrayed in pro-colonial circles as a natural disaster or the sad consequence of overpopulation, but in radical and nationalist ones as the result of a system that drained the country of wealth and resources and prevented Indians from solving their own problems.

Bose’s father was a successful lawyer with substantial government business. He wanted his gifted son to benefit from the opportunities available to high-ranking families like his own, both in his native Bengal and one day, he hoped, in the famous universities of England. But by his teens, Bose was already moving away from the attitudes that underpinned his father’s life, becoming deeply, even obsessively, interested in politics, religion, and community service. Studying and emulating his earliest hero, the popular 19th-century Hindu sage Swami Vivekananda, he volunteered to work in the poorest regions of Bengal.

His family enrolled him in the prestigious Presidency College in Calcutta, a hothouse for Indian boys destined for high office. Here he immediately stood out as both a rebel and a natural leader of rebels, finding himself at the forefront of a group of like-minded, serious and studious teenagers. All believed that India was on the point of a historic spiritual and political awakening and destined to be rid of the British in the decades to come. With his friends, Bose travelled into rural communities where bare subsistence farming was the norm. Here he got “a picture of the real India, the India of the villages, where poverty stalks the land, men die like flies and illiteracy is the prevailing order.”

Such images and ideas were surely at the forefront of the young radical’s mind when—at the age of nineteen—he had his fateful confrontation with Edward Farley Oaten. And the contradictory way that this incident was reported set the scene for the rest of Bose’s life. Consider these two conflicting ways of interpreting the incident, which I’ve extrapolated from a rich variety of sources.

Version One:

The daily indignities of living in a racially divided society cut Subhas Chandra Bose deeply. It was impossible for him to travel to and from his school, or even walk along its corridors, without witnessing displays of casual arrogance from people who had grown so used to controlling Indian lives. This made a compassionate young man, who believed so strongly in fairness and justice, quietly seethe with anger.

When he heard of Mr Oaten’s rough language and manhandling of a young boy, Bose knew immediately that the moment had come for him to stand up for the ordinary Indian.

Although traduced by the usual lickspittle commentators in the Calcutta press, Bose knew that most Indians would instinctively sympathise with someone who experienced everyday colonial insults and proudly cried “No more!”

Bose took no part in the brief, though amply justified, physical confrontation with Mr Oaten (which lasted thirty seconds at most) but he did witness it.

Showing the mix of loyalty and determination that would from that day mark him out as an inspirational leader, a true Netaji, Subhas Chandra Bose refused to name the boys who had laid their hands upon Mr Oaten, even though he knew that this honourable silence would only draw more punishment.

Teachers like Oaten, who spoke of the “civilising mission” of an empire that allowed millions to die of avoidable hunger and disease, would now walk less comfortably through the schools of this city, and every report of a teacher being “Oatenised” brought Bose much satisfaction.

The decision to suspend him from all education in the City was a typical example of colonial spite, throwing his whole family into despair. His father’s dream of seeing him travel to a British university appeared to be over.

Version Two:

One of the most popular teachers at Presidency College, Mr Oaten’s life was defined by a love for India and for Indians. He taught with sensitivity and flair, becoming almost fluent in Bengali. Believed to be a quiet supporter of independence, he was devoted to his classes and regarded his pupils as the future leaders of their nation.

Unfortunately one day a group of permanently difficult students led by the recalcitrant Subhas Chandra Bose picked up some schoolyard gossip about him and exaggerated it wildly.

He’d recently asked some boys loitering noisily in a corridor to lower their voices and, as he did so, he’d ushered one of them towards his classroom with a gentle push on the shoulder. But Bose’s group characterised this as some kind of physical attack upon a weak child. They stirred up so much trouble that a pupils’ strike was organised which then spread to other schools around the city, drawing in yet more troublemakers.

Although the injustice of this cut him deeply, Oaten offered a qualified apology and things calmed down for a few weeks until yet another unfounded rumour, this time about him actually beating a boy, raced around the school—almost certainly at the behest of the Bose gang. This resulted in a frightening physical attack. He was putting up the weekly cricket notices when he was jumped upon from behind and beaten most severely, leaving him dazed and badly bruised.

An orderly quickly identified Bose as one of the attackers and, as the city’s more sensible newspapers rightly condemned this appalling act of violence, the boy was suspended and named “the most troublesome man in the college.” But the damage had been done and in numerous other schools teachers found themselves “Oatenised,” set upon by mobs of angry children, in violent solidarity with the assailants of Presidency College.

Bose would not be allowed to study anywhere in the city for at least a year, a slight punishment indeed considering the offence and the short tempered character of a boy who was—as Oaten happily acknowledged—clearly talented in numerous other ways.

Despite these shocking and undeserved indignities, Oaten continued to be a highly successful and much loved teacher and—showing a generosity of spirit so sadly lacking in his accusers—wished Bose well. Indeed many years later he wrote an affectionate poem about his chief tormentor.

There’s something in “Oatenisation” that brings to mind E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India. A series of misread signals, the instinct to ascribe the worst possible motives to the actions of a member of a separate group or race, a confused encounter between people in contested circumstances—all coming together to spark a personal and political crisis.

Teenage rebellion versus imperial arrogance is an easy story to tell and most of us rush to take sides on issues such as this, then and now. Bose, never one to choose the less dramatic phrase, spoke of this period as his baptism of fire, his first experience of martyrdom, his first understanding of the personal price that the call to leadership would demand of him. But for all that, he was hardly nailed to a cross. Behind the scenes, some strings were pulled and some family influence peddled and within a year, the young radical was back in education, a semi-detached member of upper-class Bengal society once again, studying philosophy at the Scottish Church College in Calcutta. And within two more years he did set out for England after all, to take up a much-coveted place at Cambridge University.

Part Two: India, 1920s

British India was generally known as the British Raj, or simply “the Raj.” As they sat in their splendid palaces and grand bungalows, the men who administered it liked to boast that they ran the place with just a few thousand imported officials and a handful of filing cabinets full of clever local alliances. Given the scale of India—multiple climatic and geographical regions, over 310 million people drawn from numerous ethnic and religious backgrounds, and hundreds of quasi-independent “Princely States”—this was some achievement. They also liked to claim that, apart from a minority of agitators and troublemakers like Subhas Chandra Bose, the great mass of people across all these disparate communities were content to live under the beneficent rule of the crown. There was some truth in this as well. The sheer number of Indians would have quickly made the nation ungovernable without some kind of consensus that, although imperfect, the Raj still made sense. But that consensus was fraying and would fray even more in the 1920s and 30s as a pro-independence protest movement, whose most prominent leader was the internationally renowned Mahatma Gandhi, challenged authority and drew millions onto the streets, along with periodic outbreaks of rioting and a persistent but low level of armed resistance.

Whenever such resistance reached a point deemed dangerous it had, for a long time, been efficiently and ruthlessly suppressed. The men in charge had at their disposal an impressive modern police force, British-led but mostly Indian-staffed, supported by the Indian Army as and when required, most notoriously at Amritsar in 1919. There was also a shadowy cohort of secret policemen operating on the fringes of or quietly beyond the law, with violent interrogations overlooked by incurious judges, suspensions of civil liberties, and long terms of house arrest or incarceration in distant fortress prisons. But whatever their private feelings, many of India’s cleverest students—young men like Bose and Timmy—continued to compete for jobs in the army and the Indian Civil Service. The latter was widely described as honest and capable, although the nationalist leader Jawaharlal Nehru, channelling Voltaire on the Holy Roman Empire, famously called it “Neither Indian, nor civil nor a service.”

We focus today on the hierarchies of race in the British Empire yet, in India at least, the complex and ancient gradings of class were at least as important. The ancient caste system and a long tradition of autocratic rule in the Princely States meant that the most common form of oppression experienced in colonial India was that of poorer Indians by much richer ones. Some of the excesses and eccentricities of the numerous nawabs, emirs, and maharajas in the over 500 quasi-independent regions made the Raj look positively enlightened: rapacious tax collection, justice delivered on the whim of a local princeling, and with minimal right of appeal to higher authority, droit de seigneur exercised over young women and concubines collected by the score. Gandhi himself was known to defend the caste system—in which he personally sat near the very top—and had opinions about race relations, especially those between Asians and Africans, that shocked his liberal supporters in Europe and America.

The Raj could be flexible too. The 1919 Government of India Act brought limited local self-government, which would be much expanded in 1935. This allowed politicians in London and high officials in India alike to present themselves as agents of change. The changes might be slow but they clearly led toward devolution of certain powers and a widening franchise. Perhaps surprisingly, some leading nationalists agreed—or half-agreed—with this analysis. The prominent social reformer B.R. Ambedkar, like most of his peers, wanted to see the end of the Raj but he openly acknowledged that it was only the power of the British that gave long-oppressed groups—such as the so-called “Untouchable” class—the hope of a better future. If radicals like Bose saw India as an ancient and cultured civilisation repressed by foreign rule, Ambedkar saw it as a flawed and sometimes brutal society that the British could help improve before they left.

With all this in mind, perhaps the word “consensus” doesn’t quite capture why the Raj remained popular enough to survive. It might be more accurate to say that as more and more voices were raised for independence, it managed to present itself as the safe form of modernisation, and one that stood apart from India’s many class and religious conflicts. Historian Zareer Masani highlights the “promotion of liberal values, the rule of law, a professional civil service and parliamentary institutions across almost all its territories” as a real achievement of the Raj, and the principal reason for its longevity.

If the debate between reformers within India could be fraught and complex, the outside world mostly saw it as a simple case of outdated imperial domination. Through the inter-war decades, Gandhi, Nehru, and then Bose himself found a growing international audience for their arguments, particularly in the United States, and independence for India became one of the great progressive causes of the age. It was an issue for left-leaning Britons as well, especially in the colleges, where many of the leaders of the independence movement received their education, before or even between bouts of official harassment and arrest. Yet the administrators of the Raj did not feel they were struggling to keep a lid on an imminent revolution. Students and lawyers may have protested from time to time but the great mass of the people seemed if not loyal then at least acquiescent, and there was no shortage of smart young recruits to keep filing cabinets filled and regimental ranks swollen. Few, even amongst the most passionate campaigners against British rule, truly believed that it would all disappear completely in their lifetime.

Part Three: Bose. Cambridge and India, 1920s–1930s

Just weeks after Bose began his studies in Cambridge, troops under the command of General Reginald Dyer murdered hundreds of Indian protestors in the Jallianwala Bagh atrocity, better known in Britain as the Amritsar massacre. Somewhere between four hundred and a thousand people died when Dyer, panicking over a demonstration that he feared might turn towards insurrection, issued his command to open fire. The general was condemned in the British press and on all sides of the House of Commons. Minister of War Winston Churchill, an imperialist to his very core, described Amritsar as “an event of an entirely different order from any of those tragical occurrences which take place when troops are brought into collision with the civil population. It is an extraordinary event, a monstrous event.” Novelist Abir Mukherjee was not the first to grasp that killing unarmed demonstrators killed something in the British as well, undermining the core justification of the Raj. The Secretary of State for India himself, Edwin Montagu, demanded of those who tried to defend Dyer

Are you going to keep hold of India by terrorism, racial humiliation and subordination, and frightfulness… or are you going to rest it upon the goodwill, and the growing goodwill, of the people of your Indian Empire?

Bose spent most of his time at Cambridge with students and teachers—both Indian and British—who were passionate anti-imperialists. But as he read speeches from men like Churchill and Montagu, he surely noted that even the loudest defenders of empire could feel shame at its excesses, and also clearly state in public that the “goodwill,” or at the very least the tolerance, of the massive Indian population was an essential, inescapable, component of the Raj. The obvious implication was that if and when such goodwill dissipated then British rule would end, however many soldiers might be sent onto Indian streets.

Bose sat the challenging entrance examination for the Indian Civil Service, as his family had long wished, and although he passed with some ease, his political principles made him hesitate. He explained his dilemma in a letter to his brother:

I don’t know whether I have gained anything really substantial by passing the Indian Civil Service examination but it is a great pleasure to think that the news has pleased so many, and especially that it has delighted father and mother… A nice flat income with a good pension in after life I will surely get. Perhaps I may become a Commissioner if I stoop to make myself servile enough… But for a man of my temperament who has been feeding on ideas which might be called eccentric, the line of least resistance is not the best line to follow.

In short, national and spiritual aspirations are not compatible with obedience to Civil Service conditions.

No, Bose would not serve the British in his homeland; he would dedicate his life to replacing them. Soon back in Calcutta, he began building a following that extended far beyond university graduates, forging alliances with grass roots campaigners for reform in numerous towns and villages and growing ever more radical. He was drawn to protest groups and secret societies, some underground and illegal. Although he publicly admired Gandhi’s commitment to non-violent protest, he would not condemn those who did resort to bombings, robberies, and assassinations. One of his closest friends was the brother of Gopinath Saha, who attempted to shoot the police commissioner of Calcutta but killed another man by mistake. When Saha was executed, Bose offered condolences to his family at the gates of the prison. All of this inevitably drew the attention of the police and in 1924 he was arrested for the first time, under an ancient law that allowed the authorities to detain anyone indefinitely without trial or even a published charge, solely on the basis of the testimony of anonymous witnesses.

The authorities thought him a dangerous agitator or perhaps even a violent Bolshevik but it was more complex than that. Peaceful change through negotiation remained Bose’s stated preference and yet he could not ignore what had just happened in Ireland nor the argument—widely discussed in the circles in which he moved—that the surest way to bring politicians in London to a negotiation was to ensure that imperial rule became too expensive in terms of money, casualties or both.

For three years, he suffered inside a forbidding, damp, and draughty prison in distant Mandalay, far from his friends and family. Here his health—never strong—deteriorated and he began to show signs of the respiratory, abdominal, and gallbladder ailments that would plague him for the rest of his life. He was allowed books and read Bertrand Russell and other British liberals, along with Nietzsche, stories of Ireland’s long struggle for independence, and serious Russian novels. He was also allowed to write letters to comrades old and new and these helped to spread his name and fame all around the country. Soon, millions of ordinary Indians recognised Bose as one of the leading voices of nationalism, his idealism and capacity for self-sacrifice amply demonstrated by his incarceration. He refused the offer of an exile in Europe, which could have markedly improved his health, and chose instead to remain as a martyr in his gloomy prison, where he seemed set to languish for many more years until a new and more liberal governor of Bengal unexpectedly set him free in 1927. His fame and flair for self-promotion guaranteed him an important voice in the Congress Party and he was arrested once again during the civil disobedience campaigns of the early 1930s. The Raj was evidently unsure how to handle this irritating but popular young agitator and he experienced phases of official harassment punctuated by months of relative tolerance. In 1933 officials permitted him to travel from India to Europe for medical treatment but suggested that they may not allow him to return.

By now he was known far beyond the shores of India and wherever he went a string of prominent politicians, writers and celebrities queued up to meet him and be photographed alongside him. In 1935 he published a book destined to be one of the most influential of the decade. Called The Indian Struggle, it was an important statement about the future of the British and other European empires. It received excellent reviews in London magazines and the more serious British newspapers but back home the colonial authorities quickly banned it, thus turning every smuggled copy into a very hot property. The justification for the ban was that Bose encouraged “direct action” in the book and so might stir up violence, but in fact it was a rather measured work, containing fresh ideas about how a future independent India might govern and reform itself, some of which would come into practice just thirteen years later. One of its admirers was Irish Prime Minister Eamon de Valera who invited Bose to visit his newly independent nation, and there Bose discussed anti-imperial tactics with men who’d recently taken their freedom by carrying rifles rather than writing books. His rapturous reception in Dublin was matched in numerous other European capitals, including Paris and Rome.

He personally handed a copy of his anti-imperialist book to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, then engaged in building an empire in North and East Africa. Back in India, the Congress party could not decide how to respond to the men who had recently taken charge in Germany, the Soviet Union, and Italy, men who were transforming their nations but at the price of militarism and repression. Jawaharal Nehru was instinctively opposed to such authoritarianism but Bose himself was less certain. Although still considering himself a democrat, he was drawn to the idea that, to make the sweeping changes India needed, a strong governing party imposing a military style of disciple may be necessary. “Nothing less than a dictator is needed to put our social customs right,” he explained in one private letter, and it wasn’t hard to guess who he already had in mind for the role.

He was hardly the only young politician in the mid-1930s to think like this. Many people, disenchanted with capitalism and dismayed by the global economic slump, looked at what was happening in Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union with open admiration. Stalin’s ability to transform a backward, mostly agrarian society into an industrial powerhouse within a single generation was of obvious interest to nationalist leaders from poor nations currently living under the control of Europeans. Stalin’s men, and his sympathisers in Europe and the USA, did a good job of downplaying the sinister side of his rule—the show trials, the gulags, and the man-made famines—and much use was made at this time of phrases involving the making of omelettes and the breaking of eggs. There was also an undeniable glamour to the dictators of this decade, whether communist or fascist: the mass rallies, the ranks of strutting soldiers, the burning torches and the “Triumph of the Will” rhetoric. Bose had yet to don a uniform or address a military parade, but did he already imagine himself in just such a role: the “Father of his People” at the head of a transformative paramilitary state?

Part Four: Timmy. Sandhurst and India, 1920s–1930s

Perhaps consider it like this. You’re playing rugby and you fall straight into a pile of dog shit. It’s all over your hands, maybe your face. So what do you do? Grab some newspaper, wipe yourself a little and carry on. Or do you run for the nearest water tap as fast as you can? Now, if you treat your hands like that then why not your precious British arses?

It was largely pointless, but the small number of Indian cadets at Sandhurst did from time to time attempt to spread the benefits of their culture and, lavatory habits apart, Timmy was pleasantly surprised at how much his fellow students were open to foreigners and their ideas. He experienced little trouble on account of his race—certainly far less than he’d seen at schools in India—and instead found that it made him stand out as somebody different and interesting. There was plenty of colourblind brutality though, and all endorsed by the senior officers who ran the place. The first few weeks of relentless drilling “on the square” marked out the new entrants for a range of cruel and ingenious after-hours punishments meted out by the older cadets. But Timmy was tough and hit back when he could, and once the “square bashing” phase was over, his status quickly began to rise as the curriculum focused on all the things that he was good at. There was strenuous outdoor physical exercise, intense body conditioning in the gymnasium, cricket, hockey, horse riding, rugby, football, and a new enthusiasm—boxing. In between all of that, there were lectures on weapons, tactics, styles of leadership, and military history delivered by some of the cleverest men in the British Army and academics drafted in from the top universities. He was happy and popular during what he called eighteen of the best months of his life. He even spent a blissful few weeks in Switzerland with a group of friends mastering winter sports.

The only time when being a “colonial” seemed to count against him was when he won his “spurs” by excelling on an equestrian course. This should have entitled him to the formal award of a “College Blue” but it never arrived. The rumour mill told him that Gandhi’s well publicised agitation was causing a few of the senior lecturers to question the loyalty of their Indian students, but he was never given a proper explanation. Posted back to India as a newly qualified lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry, he would soon witness political demonstrations first hand. He’d also experience some of the notoriously “loose” behaviour of the white officers of the Indian Army, behaviour that had long offended conservative and religious Indians. There’s a good sense of this—and of the openly promiscuous culture of many interwar regiments—in the written examination questions that the army set for its own officers in the 1920s.

You are Capt. P.O. de L. FAKER, 1st. Bn. THE ROYAL THRUSTERS (Henry the Eighth’s own) and you are a rival to your C.O., Lieut-Col E.M. BRACER in the affections of the frail and fascinating Mrs I. LOVETT. The lady has informed you that her husband is in RAZMAK for the summer, while she will be in MUSSOOIRE.

Lieut-Col BRACER is

(a) Of a somewhat brutal nature.

(b) Furiously jealous of your success with the lady.

(c) Acquainted with her movements.

(d) Convinced that you are a rotten officer.

(e) Aware that you have already had more than your share of leave.

REQUIRED FOR EXAM.

A letter applying for two months leave to MUSSOOIRE.

Another challenge from the Indian Army Staff College, Quetta, 1926. Staff Writing Exercises. Letter #3.

— Robert Lyman 🇺🇦 (@robert_lyman) December 12, 2022

You are Captain P.O. de la FAKER of the 1st Battalion The Royal Thrusters (Henry the Eighths Own)…

Have a go! pic.twitter.com/bImlyPz9uy

Men such as the gallant Captain “Poodle-Faker,” 19th-century slang for a young seducer, and his rival E.M. Bracer, were common in Timmy’s new regiment. The white officers pursued each other’s wives, brought local girls to their rooms, and openly visited prostitutes. Timmy found all of this shocking but it passed almost without comment in an officers’ mess where the phrase “sowing one’s wild oats” was often spoken. This perhaps explained the constant absence of officers and men alike due to venereal disease. Most of the supposed “Highlanders” under his command actually came from in and around Glasgow. They were tough men and heavy drinkers too. Fights were common and they were not above taking a swing at an officer, even one as physically intimidating as Timmy. He discovered that they responded well to firm leadership, tough language and sometimes his fists, but there were some unavoidably comic communication issues. When he accused a soldier of being drunk on duty the man replied, “I don’t mind it, Sir.” “Well you bloody well should mind it,” Timmy exploded, “and you should mind your insolence even more because I’m taking you up before the company commander on both charges.” Later the commander gently explained to him that “I don’t mind it” in the Glasgow dialect means “I don’t remember it.” He never came upon any open prejudice on account of his colour but he couldn’t help noticing the strong animosity towards any English officer who found himself in command of the Glaswegians.

The Indian Army consisted of battalions from Indian and Gurkha regiments (and their mostly white British officers) mixed in with a minority of all-British battalions such as the Highland Light Infantry. The Scots rated Timmy as a promising young officer but he longed for the chance to command real Indian troops. That eventually brought a transfer to the regiment that would become his military and perhaps even his spiritual home for the rest of his life—the Hyderabad. Most of the white officers in his new base of Allahabad were pleasant enough but some clearly resented the wave of Indians rising through the ranks, especially at a time of continuing political strife when they might be called out into the streets at any time. Timmy’s new commander, Colonel Hamilton-Britton, worked hard to smooth out any tensions and even arranged for his Indian officers to join the kind of smart colonial clubs that Timmy had long admired, most of which had only recently begun to accept non-whites.

Indian soldiers took time to adjust to officers who looked like them. For as long as anyone could remember they had seen the British as in some way natural commanders and internalised colonial prejudices about their fellow countrymen: that they were poor decision makers; that they would abandon their men in a crisis; that they would be corrupt. But it didn’t take long for Timmy to receive letters from the relatives of his jawans thanking him for what he was doing and revealing that the soldiers he commanded were actually bragging about being under Indian officers when they visited their home communities on leave. This made him feel intensely proud and helped him develop a belief that a fully Indian Indian army was not only inevitable but would be the key to independence. His political ideas deepened when he made a very important new friend. A mutual acquaintance introduced him to none other than Motilal Nehru, one of the grand old men of Indian politics and father of the famous Jawaharlal Nehru. On their first meeting Nehru asked Timmy a most uncomfortable question, demanding to know why he had willingly chosen to wear the uniform of a coloniser and an oppressor. Answering bluntly, Timmy did not seek to defend the Raj as an institution but he did speak up for the Indian Army and explained his belief that it would one day be an essential part of a free nation. Pleased with this answer, Nehru made Timmy a regular guest.

One day, the Hyderabad battalion team was playing a hockey match in Allahabad against the police when a large crowd gathered in the nearby park waving Congress flags, ahead of an address from Gandhi himself. One of the British police officers let slip that “We are going to cut off the electricity so that no one will hear the speech.” The Indian soldiers quietly passed word to the organisers of the rally who then carefully arranged the audience and placed “sub speakers” every fifty yards or so, allowing Gandhi’s words to pass quickly through the crowd. Timmy listened to every one of them. Nationalist protests like this could turn ugly and he feared what might happen if his men were ordered to suppress one. After a series of graffiti attacks and vandalism in the area around Allahabad he was told to organise a “flag march,” literally a way of showing the flag and demonstrating military force. He was to lead an armed battalion through the countryside to remind people that the authorities were still firmly in control. He thought of resigning over this but Motilal Nehru changed his mind during a conversation that revealed much about the complexity of Indian politics and protest at this time.

First nothing would please the British more than your resignation. For thirty years we’ve fought for army ‘Indianisation.’ We’re now winning the fight. If you give up, we shall have lost it. But that's not the most important reason you must continue. We’re going to win independence. Perhaps not this year or the next, but sooner or later the British will be driven out. When that happens, India will stand alone. We will have no one to protect us but ourselves. It is then that our survival will depend upon men like you.

Part Five: Bose, India in the 1930s

Bose returned home in the spring of 1936, a leader in waiting. Familiar games of catch and release immediately recommenced. He was arrested within hours of disembarking from his ship but this time allowed to live in relative comfort and granted “walking privileges,” so he could exercise outside the bungalow in which he was confined. But even under lock and key he posed a problem. In 1937, Congress was due to elect a new leader and Bose was the outstanding candidate. Did high officials in New Delhi really want the man at the apex of India’s independence movement, one publicly committed to non-violent means, to be sitting in one of their prisons? Once again Bose’s poor health provided a good excuse to let him go, and the tens of thousands who attended huge rallies to hear their hero speak immediately acclaimed him.

Bose was working on a second book, called Indian Pilgrim, an autobiography that blended political vision with religious and philosophical insight, covering everything from love and sexual relations to “the idea of the self.” Much of this had been prompted by a passionate romance with an Austrian woman called Emilie Schenkl, who had worked as his secretary while he wrote The Indian Struggle.

Bose’s unfinished autobiography reveals his desire to blend political with spiritual leadership, a belief that he could become—and perhaps already was—a mystic, or even a guru, as well as a president in waiting. His politics, every bit as much as his belief in the power of love, flowed from “yogic perception” and trying to grasp “the essence of the Universe.” But before he could become India’s new philosopher-king, Bose had to navigate his way through the more mundane world of politics. Another high profile visit to Britain saw him warmly and widely welcomed by politicians from Clement Attlee, a future Labour Prime Minister, to the “conservative’s conservative” Lord Halifax, a previous Viceroy of India and a future foreign secretary under Chamberlain and Churchill. He spoke at Cambridge and was called “India’s de Valera” in the press. He met with the real de Valera for a second time too, and once again their conversations focused on the question of when to fight and when to talk when it came to dealing with the British state. On a visit to Austria, he married Emilie in a private Hindu ceremony, although neither of them publicly spoke of it and it was not registered with any civic authority.

In January 1938, as expected, he was chosen to be the new President of the Indian National Congress, the high point of his political life, or at least the part of it that took place within the mainstream of constitutional politics. He’d been in and out of prison and subject to a range of judicial sanctions that had probably taken years off his life and yet, at this point, it very much looked like he was embarking on a transition that prefigured that of numerous other postcolonial leaders. He’d impressed the British, and not only those on the left. He’d met with government insiders and top civil servants. He was clearly someone that the London establishment thought it could work with, if not now then soon.

Bose’s first great speech as the president of Congress was markedly moderate, and much of it anticipated and predicted the commonwealth-style relationship that exists between Britain and India today. He spoke warmly of the ordinary British people he had met, people who shared his hope for a freer, fairer world. He paid tribute to Gandhi and his doctrine of satyagraha too, praising “active resistance… of a non-violent character.” As if to reinforce this evolutionary approach, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine in March 1938, described as a man of the future. But signs of a different Bose continued to emerge. The other Congress leaders found him arrogant and irascible. The word “demagogue” was whispered and even Gandhi began to intrigue against him. In return, Bose alleged that moderates in the party were secretly talking to British agents behind his back. Perhaps to counter this, Bose arranged a private meeting of his own with Nazi party officials in Bombay. No records were kept but it was unlikely to have gone well. At this stage, Hitler was making no secret of his admiration for the British Empire and had stated that he would “far rather see India under British domination than under that of any other nation.”

As relations with his comrades in Congress gradually worsened, an imminent European war re-ignited Bose’s revolutionary spirit. It also generated more signs of his positive, or at least ambivalent, feelings about Hitler’s Germany. When uniformed men from the kind of militias and youth movements that interested Bose ran riot during Kristallnacht in November 1938, destroying Jewish property and violently attacking its owners, the scale of the threat facing Europe’s Jews became frighteningly clear. In India, some Hindu journals printed strikingly antisemitic arguments defending the Germans. Most leaders of Congress disagreed and said so, but Bose opposed this position and refused to support a motion offering Jews refuge in India. At this time, many other nations were also being hard-hearted towards Jewish refugees, and long dormant antisemitic feelings were being aired all around the world. Nevertheless, as Hitler steered his nation towards a war of conquest and extermination, it was an early indication that Bose would not over-concern himself with the suffering of the Führer’s principal victims.

Part Six: Timmy. The North West Frontier, 1930s

By the mid 1930s, Timmy was based in Quetta, serving on the famous North West Frontier, the region that porously divided India and Afghanistan. It was a classic imperial policing role and here, in between dealing with bands of tribal warriors, he witnessed the Indian Army engaging in one of its favourite pastimes—sexual scandal. A friend of Timmy’s from a Sikh regiment, another newly “Indianised” unit, was caught having an affair with the wife of a fellow officer. She was white and he was not, which led to much grumbling in the clubs and the officers’ mess. The grumbling had nothing to do with sex. There were plenty of enthusiastic “E.M Bracers” and “I. Lovetts” active in the military community. In fact, a group of officers and their wives were openly organising events that today we’d call swinger parties and nobody seemed to care very much about that. And Timmy’s own commanding officer, when a captain, had deserted his wife to live with the wife of a junior officer, who had himself then moved in with the Captain’s abandoned partner. The four of them still remained in the base enjoying these unconventional relationships, although the women would sometimes “snarl” at one other after a heavy night in the club. No, the problem with the “Sikh affair” was that in this case love, or at least lust, had for the first time broken through the colour bar. Timmy looked on with a mixture of disapproval and sly pleasure:

We were amused by the flap it caused among the British. Some of us, including me, were delighted that one of our group had outridden all the British hunters and “won the brush of the prettiest vixen in the field.” But other brother officers feared that our position might be jeopardised by such a juicy scandal.

When he spoke about this many years later, Timmy said that, if anything, it smoothed relations between the races in his unit. Indian politicians and agitators tended to speak in pseudo-religious tones that the British loved to parody as sanctimonious. So a little red-blooded wickedness from a fellow Indian officer made them all seem a lot more human, and certainly a lot more British. Timmy fell in love himself at this time, but in a much more traditional way. In a marriage more or less arranged by the two families, and after a single short meeting, he agreed to wed eighteen-year-old Nina Cariappa, a distant relative from his own Coorg community. Despite their very different life experiences, and an eleven-year age gap, the relationship was a great success from the start. Nina, who had been educated partly in Europe, was confident, stylish, and spoke perfect French. Unlike some of the other Indian Army wives, she neither wanted nor expected to live any part of her life in purdah, socially secluded from men, and she soon became an enthusiastic and much prized member of the very active Quetta social scene. One of the first invitation cards she received came from Sir Norman Cater, the head of the Quetta district and a former Chief Commissioner of Coorg where he had known both Timmy’s and Nina’s families well. The district military commander, General Sir Henry Karslake, and his family also became close friends of “the Timmys,” as they became known, and he had coffee with them most days after his morning horse ride.

Timmy’s experiences on the frontier strongly reinforced his view that the army would be key to independence. Whether British- or Indian-led, he had no doubt that a substantial and well-run military force would be required to control the fierce, vendetta-ridden, and rapacious Pathan tribes of this isolated region. British political agents, backed up by the Indian Army, had spent years perfecting a mixture of bribery and brute force that managed to keep the settled population living down in the valleys mostly safe from predation. But in 1935, it almost broke down completely when a disastrous earthquake shattered Quetta and towns for hundreds of miles around. With all roads closed and only a limited number of planes and airfields available to bring in aid, it fell to the army and the police to organise search and rescue, provide medical care, place the homeless in tents, ration and administer whatever food could be secured and, most pressingly of all, deal with the swarm of merciless looters that immediately descended from the hills.

No amount of military training could have prepared Timmy for what he experienced here. His men and their families, Nina included, worked until they were sick with fatigue, using picks, shovels, and even their bare hands to pull people from under the tons of tangled wreckage that used to be a city. But they could not reach everyone crying out from under the rubble in time. Vultures fought over the corpses in the street. Jackals and rats tried to eat the wounded and the dead alike. But worst of all were the human scavengers who stole and killed without pity. Dead bodies were stripped of anything of value and left naked in the street and Timmy’s men even found injured survivors, sometimes still half-buried in the ruins of their own homes, with ears and fingers cut off so the looters could more easily grab their jewellery. Back in Allahabad, Timmy had vowed never to give an order to shoot his fellow countrymen, but he enthusiastically did so here. His troops also tied captured tribesmen to trees and lashed them in public, in the vain hope that news of such humiliation might stop the frenzy.

Nina took up smoking cigarettes to help cover the stench of death hanging over the city and helped nurse twenty survivors inside her and Timmy’s own home. She later received a national award for her heroism during this overwhelming emergency. Over 60,000 people died but that number would have been much higher without the efforts of Timmy’s men and the other military units deployed in and around the city. He was forever proud of what the Indian Army did here and it showed that the Raj system could still deliver security and decent governance under pressure.

Timmy was a captain now and pressing for admittance to the Indian Army’s Staff College, an essential step for anyone who dreamed of commanding brigades, divisions or even entire armies. His own Uncle Bonappa Thimayya had been one of the very first Indians ever to take the course. But before he could make the move Britain, and so therefore India, was at war.

Excerpted from 1945: The Reckoning: War, Empire and the Struggle for a New World by Phil Craig. Reprinted by permission of Hodder & Stoughton. Copyright © 2025 by Phil Craig.