Politics

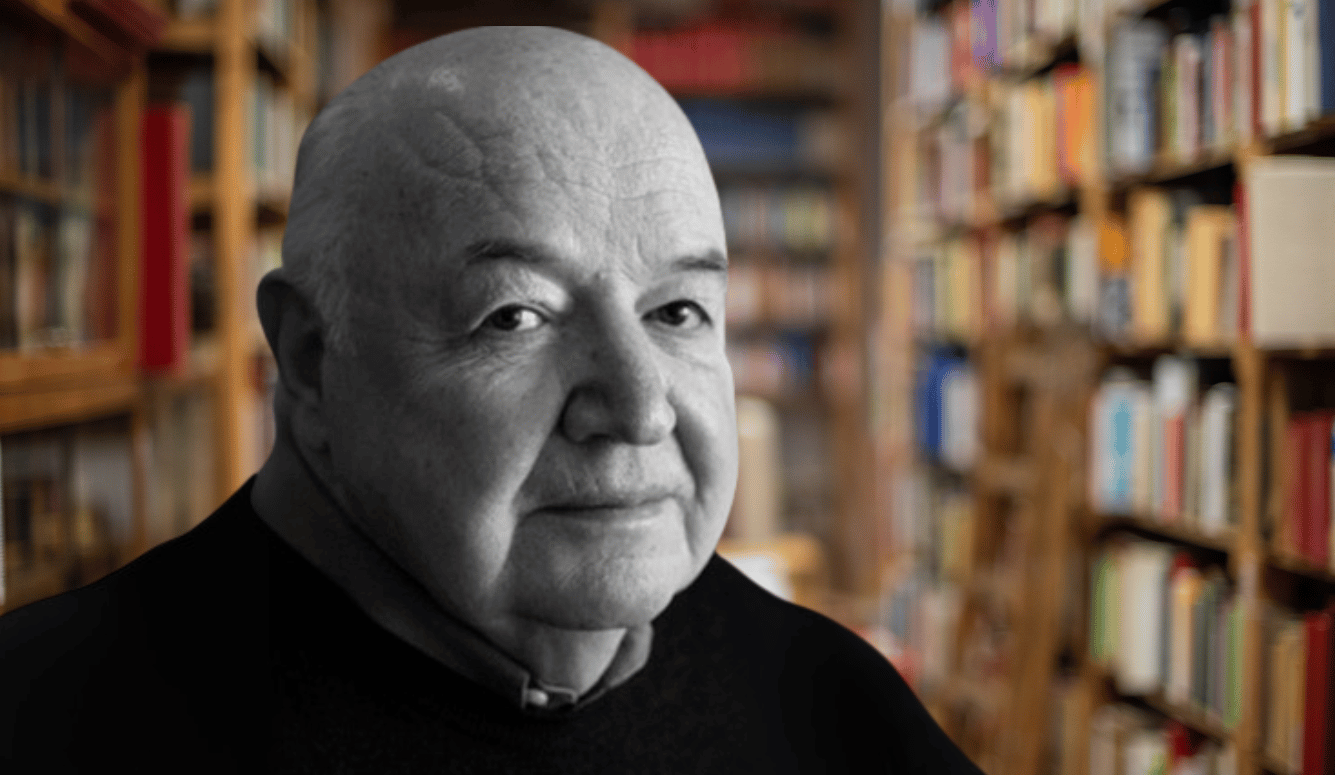

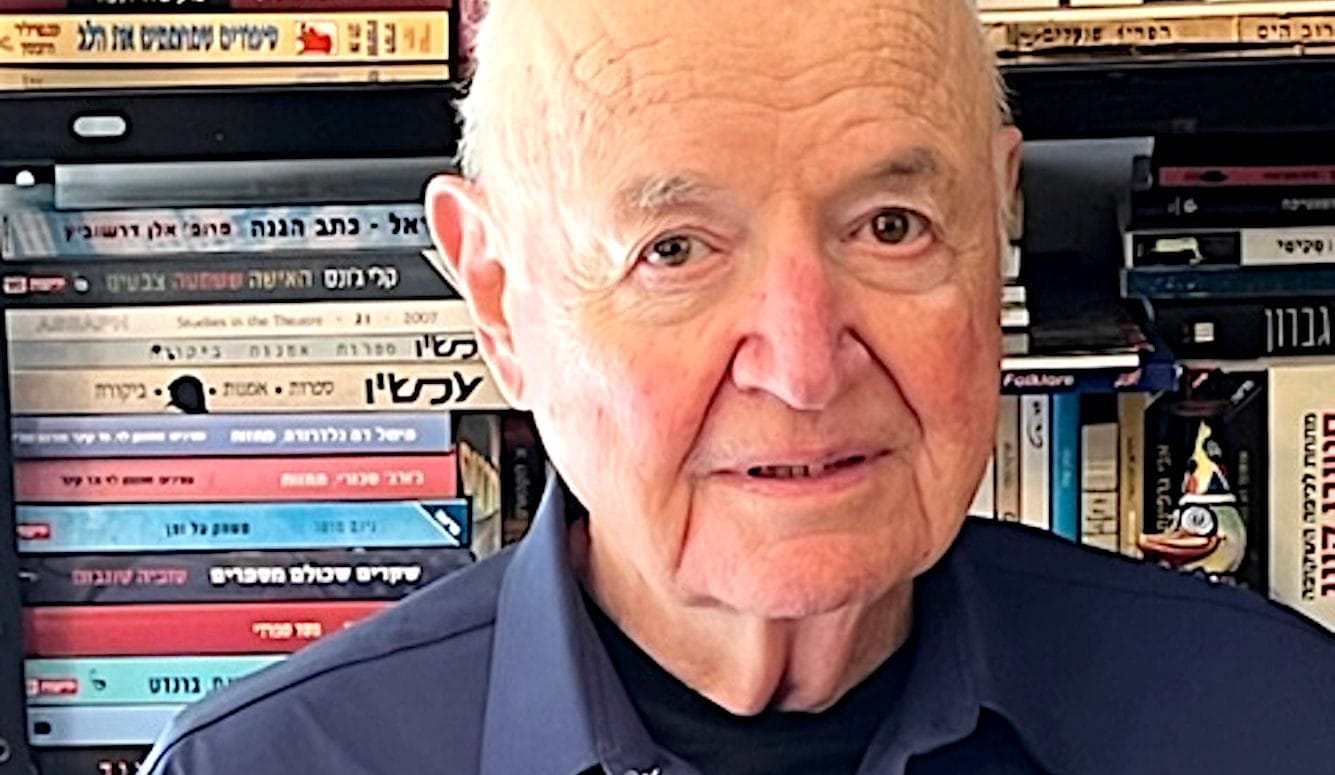

Sol Stern 1935–2025

A tribute to a brilliant writer and a journalist of great integrity and candour.

I.

On 11 July, I lost an old and dear friend, journalist Sol Stern. That loss was not just my own, it will also be felt by those who have read and learned from his writing since the 1960s. As a young radical, Sol wrote about that decade’s New Left and then its turn towards extremism and violence. Later, he wrote thoughtfully about the crisis in American education, and most importantly, about the need to defend the state of Israel from its enemies on the Left and the Right.

I first met Sol in 1959, when we were both graduate students beginning a Master of Arts degree at the University of Iowa. Sol’s degree was in political science while I was starting my journey to become a historian of recent US history. We hit it off immediately. We were two young Jewish New York leftists in the heart of the Midwest. I was then a die-hard Marxist-Leninist, while Sol was a Norman Thomas type of democratic socialist and a fierce anti-communist. Nevertheless, we became close friends and agreed to disagree about our sectarian differences (something that often feels impossible in today’s polarised atmosphere).

Together, we formed what we called the Socialist Discussion Group, and in a short time, we had recruited around fifty members, including a native Iowan who later became a member of Congress and made a name for himself during the Nixon Watergate hearings. Another was a poet (and folksinger) who would one day be appointed the US poet laureate. Most of the early group members were Jewish New Yorkers of an intellectual and political bent, who were part of a local folk-music community, and either studying in the famous Iowa English department or majoring in political science and history.

Sol and I were at the University of Iowa together for just a year before Sol left to study for a PhD at the University of California in Berkeley. There, he met David Horowitz and they co-founded a national New Left cultural magazine named Root and Branch. Some fifty years later, Sol called it one of a few “foundational New Left publications” that “proclaimed opposition to the dominant trends in American society and our independence from the certainties of the old Marxist Left.” Sol was then recruited by Warren Hinckle to join the editorial board of Ramparts, the New Left’s first mass-circulation magazine, alongside Robert Scheer and later David Horowitz and his friend Peter Collier.

In 1967, two of Sol’s essays received national attention and made headlines in the mainstream press. The first was what Sol later described as “a story exposing the CIA’s secret penetration and financing of the National Student Association (NSA).” The New York Times’ headline about the piece read: “Ramparts: Gadfly to the Establishment.” Sol’s article would receive the prestigious George Polk Award for Investigative Journalism. The second essay was a glorification of the Black Panther Party’s leader Huey Newton, an edited version of which reappeared in the New York Times Magazine. That article was responsible for popularising the image of the Panthers as a vanguard that agitated for armed socialist revolution and expressed the rage of the black underclass.

During the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, hundreds of young people chanted “The Whole World Is Watching!” as they were beaten and tear-gassed on the streets of Chicago by the police before the media’s cameras. Reflecting on Ramparts’ coverage of the Convention decades later in a 2018 article for Tablet, Sol noted:

To be sure, Ramparts produced an emotionally satisfying narrative about a criminal war, righteous young protesters, and brutal Chicago cops. But we missed a golden opportunity to provide a more complicated yet historically accurate account. We didn’t dare publish the one story we owned exclusively—how Tom Hayden and a small group of pro-communist (i.e., pro-Vietnamese Communist) activists had cynically planned a violent confrontation in Chicago in order to open another front in the war and to aid the Vietcong. The slogan “bring the war home” had become a destructive revolutionary fantasy and we should have called it by its name. Ramparts thus failed the test of true journalism, even the “new” journalism.

After Horowitz and Collier took control of the magazine, Sol wrote, it “made common cause with the most unhinged elements of the revolutionary left,” publishing “Tom Hayden’s broadsides calling on radical students to ‘smash the state,’ while also promoting the gun-toting Black Panthers as ‘America’s Vietcong.’” The magazine reached its nadir, he recalled, “with its cover showing a burning Bank of America branch in Southern California [torched by New Left activists] with a text declaring that the students who firebombed the building ‘may have done more for saving the environment than all the Teach-ins combined.’” By 1975, “I had left my youthful radicalism far behind and was beginning a long journey towards a moderate, sane conservatism.”

II.

Sol’s integrity as a writer and thinker was especially evident in his willingness to reassess his beliefs publicly and make his new beliefs known, despite the slander and outrage he endured from his former comrades as a result. He and I did some re-examining together when we co-wrote an essay reviewing the case against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, two Soviet spies sentenced to death in 1951 for “conspiracy to commit espionage.” As the time, I was still a member of the DSA and Sol had not yet embraced conservatism, but the Left’s unwillingness to accept the truth of the Rosenberg case bothered us both. Until our article appeared in the New Republic in June 1979, most of the American Left still believed that the couple had been framed by the FBI. The US Government (or so the theory went) needed a scapegoat to explain how the Soviets were able to make an atomic bomb much faster than expected. Our article caused an uproar, and the New Republic received more letters to the editor—many of them from furious leftists—than it had in response to any other issue of the magazine in its decades of publication. It received further attention when Sol and I appeared together on NBC’s Today Show to discuss it.

In 1983, the writer Joyce Milton and I expanded and updated the article into a book about the case titled The Rosenberg File, which contained a lot of new material, some of which Sol had collected in new interviews. That October, Sol, Joyce, and I debated Walter and Miriam Schneir, who had co-authored a 1965 book titled Invitation to an Inquest proclaiming the Rosenbergs’ innocence. The event was held in New York’s famous theatre, Town Hall, and it was Sol who brought down the house when he referred to something Miriam had told him in a telephone interview. Miriam said we had made it up and accused us of lying. At which point, Sol produced a tape recorder and played the phone interview into the microphone. The large audience broke into raucous laughter—it was, many people told us, the evening’s highlight.

During the 1990s, Sol became a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative New York think-tank, and wrote scores of essays for its in-house publication City Journal. He became particularly interested in education policy during this period and published a short book in 2003 making the case for school choice. Sol came to believe that charter schools would allow working-class and black inner-city kids to access the learning to which they were entitled. In a tribute published shortly after Sol died, his former editor Brian Anderson wrote, “Sol became one of the country’s sharpest critics of education orthodoxy, taking aim at politicized pedagogy, content-free curricula, and the destructive influence of Paulo Freire, Lucy Calkins, and other so-called educators.” Instead, Sol endorsed the educational theories of E.D. Hirsch, who emphasised the need for a common core of general knowledge (which Hirsch called “cultural literacy”) before students could move on to areas of particular interest.

But as Anderson acknowledges, Sol would later rethink his advocacy for charter schools as well. Indeed, as the Manhattan Institute’s policy on this topic was not yet firm, Anderson ran an article by Sol in 2008 titled “School Choice Isn’t Enough.” Sol studied new reports on the results of education in nationwide charter schools, and concluded that, with only a few exceptions, they failed to give their students a basic education. Test scores showed that, like their public-school counterparts, most charter schools produced much the same results as their free counterparts in the city centres. As Anderson recalls, “Sol broadly supported school choice, but he came to believe that its backers paid insufficient attention to the content of classroom instruction.”

Sol spent many productive years at the Manhattan Institute and City Journal, but the Trump revolution ensured he could not settle there. He ended his 2018 essay for Tablet by remarking:

At City Journal I was part of a writer’s community valuing ideas, debate, and civility. One of our intellectual heroes was the anti-totalitarian thinker, champion of classical liberalism and fierce opponent of populism, Friedrich Hayek. I was thus shocked that my colleagues weren’t willing to speak out against the new right-wing populism exemplified by Bannon and Trump. When City Journal then made it clear that I wouldn’t be allowed to write anything critical about President Trump or these deplorable developments in the conservative intellectual world, I resigned in protest. It was almost a half century since I had drifted away from Ramparts because I wouldn’t be allowed to write critically about Tom Hayden’s agenda for America.

Our country survived the political fevers brought on by the mindless radicalism of the 1960s. As a never-Trump conservative I’m much less confident about America’s ability to survive the assault on truth and liberal values now coming from both directions, the left and the right.

Writing about his resignation in an essay for Democracy Journal in 2020, Sol reflected:

After the shock of the election results [in 2016] sunk in I assumed that City Journal couldn’t just ignore the danger to the country now emanating from the highest office in the land. Once again I was naïve. Writers who wanted to sound the alarm about the new President were still muzzled; in fact, the magazine published a number of articles welcoming the Trump ascendancy.

Sol attributed this to the institute’s two main benefactors, Paul Singer and Rebekah Mercer, both of whom had strongly supported the Trump campaign and were now supporting his presidency. He believed they had told the editors at City Journal that money would not be forthcoming if the magazine refused to fall in line. So, he left in October 2017.

That move became something of a cause célèbre. Bari Weiss wrote about Sol’s decision in an article for the New York Times (where she still worked) titled “The Trump Debate Inside Conservative Citadels.” Why was Sol the only person at a conservative institution who quit after he was told he could not write about his disagreement with the Trump agenda? “I’m 82 years old,” he told Weiss. “I want to say what I believe and feel a little cleaner.” Weiss went on to quote from Sol’s resignation letter and observe that:

Think tanks are chiefly supposed to provide independent expertise to policymakers. But they also seek to be politically relevant. To be relevant, you need access. And, of course, they also must answer to well-heeled donors, like the Mercer family, whose political loyalties are sometimes vehemently pro-Trump.

This reality leaves these institutions with an uncomfortable choice: fellow-travel with Mr. Trump or let the Trump train pass your station and risk diminishing influence in a Washington where he is boss.

Towards the end of the article, she quoted me: “Bannon and Trumpism,” I said, “is a definitive threat to the country. The ideology is a dramatic departure from a long American tradition of America being a global leader,” and “a fundamental rejection of liberalism.” Having rejected the radical populism of the New Left in our youth, Sol and I were now in agreement about the dangers presented by the radical populism of the New Right. In our current moment, it is rare to find writers and intellectuals, especially in their twilight years, willing to look back and re-examine ideas and beliefs and risk estrangement from friends and allies. Sol’s independence of mind proves that age is no excuse for dogmatism or tribalism.

III.

Sol’s greatest passion was the fight to defend the state of Israel, which began while he was still at Ramparts. At the time, leftwing opinion was starting to shift against the Jewish state under the influence of the antisemitic Black Panther Party and other parts of the radical New Left galvanised by the PLO’s revolutionary terror. Since Sol was one of Ramparts’ top writers and a former editor, the editors bravely ran a major eleven-page article he wrote defending Israel from attacks by its leftist enemies after his first visit there in 1971.

Titled “My Jewish Problem—and Ours,” and published when Sol still considered himself a good leftist, the article intellectually dismantled the logic of his anti-Zionist comrades. Re-reading it in 2025, I was stunned by its prescience. Many of the arguments Sol identified as dangerous then have become a familiar part of leftwing discourse today. In 2003, Sol recapitulated the main points of his Ramparts article in an essay for City Journal titled “Israel Without Apology”:

When I returned to Berkeley, I wrote about my visit for Ramparts, the flagship publication of the New Left, of which I had been an editor. Thanks to my leftist bona fides on virtually every other issue, I had permission to deviate from the party line on Israel. It was the first and last time that anything remotely sympathetic to the Jewish state appeared in Ramparts or in any other New Left journal.

Still, my article was no ringing endorsement of Israeli policies—only an effort to convince my fellow leftists that Israel was more complicated than their vulgar Marxist categories allowed. For authority, I cited the work of Marxist historian Isaac Deutscher, an icon of our antiwar movement, who during the 1950s had expressed sorrow that his doctrinaire anti-Zionism had kept him from urging European Jews to go to Palestine, where they might have escaped the gas chambers.

Ever self-critical, Sol acknowledged that, as a member of the New Left, he missed the vitality of an ecumenical Israel, which “made me realize how untenable were my left-wing politics.” When the Left looked at Israel, it just saw an imperialist settler-colonial nation. What Sol found when he went there, he said, was “a vital, open society, with virtues that any liberal-minded person should have cheered. Israel was democratic; it was pluralistic; it was equalitarian; it was productive.”

But Sol was also impatient with the position on Israel taken by writers at Commentary (for which he would write major articles in later years), who he complained wanted to sever “all relations between radicalism and the Jewish community.” This, Sol argued in his Ramparts essay, would be a disaster because the American Left needed Jewish elements in it willing and able to make the case for the “national and cultural aspirations of the Jewish people.”

In recent decades, Sol concentrated on exposing the dangerous path taken by Palestinian spokesmen and movements, who he accused of slandering Israel. In a brace of articles for Commentary in 2023, he sought to set the record straight. “It’s Not the ‘Occupation,’ Stupid” dissected the Palestinians’ insatiable hatred of Jews, and argued that the problem was not Israel but thoroughgoing Arab antisemitism. “The Truth Behind the Palestinian ‘Catastrophe’” exposed the Palestinians’ foundational myth—that the creation of Israel required a war against Arabs by the Jews, which they now call “the Nakba.” That claim, Sol argued, represented “an ongoing public-relations triumph for the Palestinians—and a victory for deceit and disinformation.” It was a myth, he wrote, that “depicts the founding of Israel as a catastrophe that resulted in the dispossession of the land’s native people.” Anyone who believes the Palestinian narrative and reads this article will think twice before accepting that Palestinian claim as the truth.

Nevertheless, Sol’s devotion to Israel was tested by the current administration, particularly after Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appointed two far-right extremists to his cabinet to shore up his political majority. Bezalel Smotrich was made minister of finance, and Itamar Ben-Gvir was made minister of national security. Ben-Givr is an anti-Arab extremist, who has been convicted of many crimes, including incitement to racism and support of the Kach Party, an Israeli terrorist group banned in 1994. “The American equivalent,” Sol told me, “would be appointing the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan to be head of the FBI.”

Sol’s support of Israel was indisputable, but during our final telephone conversation a few weeks ago, he told me, “I feel homeless. The two countries I am citizens of and love, the United States and Israel, have both moved together towards authoritarianism.” While in Israel, where he lived for the last three months of his life, he regularly attended anti-government demonstrations to protest Netanyahu’s proposed judicial reforms. He was also conflicted about the government’s prosecution of the war in Gaza, and joined those demanding that the administration do whatever was necessary to secure the immediate release of the remaining hostages held by Hamas. “I never felt prouder being in mass demonstrations than I did participating in the ones in Israel,” he told me.

It infuriated him that many on the American Right were characterising these protests as unimportant and politically sectarian. To the contrary, Sol said, the vast crowds included Israelis young and old from across the political spectrum, all of whom were proud patriots. He saw many people he knew on those marches, including many IDF soldiers, most of whom were unfriendly to whatever small leftist sects still exist in Israel. These were not activists from small left-wing fringe contingents. To characterise Netanyahu’s opponents in this manner was to misunderstand or misrepresent the country and its people. Writing off the opposition as leftist malcontents was as misguided as the international Left’s contention that Israel was an imperialist outpost.

As usual, Sol called things as he saw them—he remained fiercely supportive of Israel’s existence, but reserved the right to be vehemently critical of its government when he felt poor leadership was betraying the nation’s foundational ideals and endangering its very existence. Just before be died, he told me he was working on what he considered to be “the most important article I’ve ever written.” In that unfinished piece, he said he would argue that Israel’s current leadership is no longer Zionist. Zionism meant creating a Jewish state that would provide a refuge for Jews fleeing antisemitic nations, in which all Jews would be welcome. But the cynicism and irredentism he perceived in the Netanyahu administration combined with the abject security failures on 7 October 2023 caused him to doubt that the government could still be trusted to discharge that responsibility.

Throughout his life as a political journalist, Sol Stern strove to remain true to himself, to his values, and to the available facts of whatever matter had his attention. He was a rare soul willing to rethink and reappraise his position in the light of new information even when this caused painful separations and blowback. If he found his old views to be obsolete, his honesty compelled him to explain how and why they had changed. He was a brilliant writer and journalist and a man of great integrity and candour. As a devoted husband, father, and grandfather, he delighted in living a good life in as meaningful way as possible. His memory is indeed a blessing.

The two essays Sol wrote for Quillette can be found here.