Fertility

Falling Fertility: A Crisis We Refuse to Face

Fertility decline is not merely a demographic curiosity—it is a structural challenge with civilisational implications. So why are people so reluctant to take it seriously?

We are in the throes of a global crisis, which touches every nation, threatens our economic prosperity, and if left unaddressed, could bring about the demise of the human species. Yet we have no agencies dedicated to responding to it, have invested no major funding into researching it, and almost never talk about it in the political sphere. This is the situation we face with regard to our declining fertility.

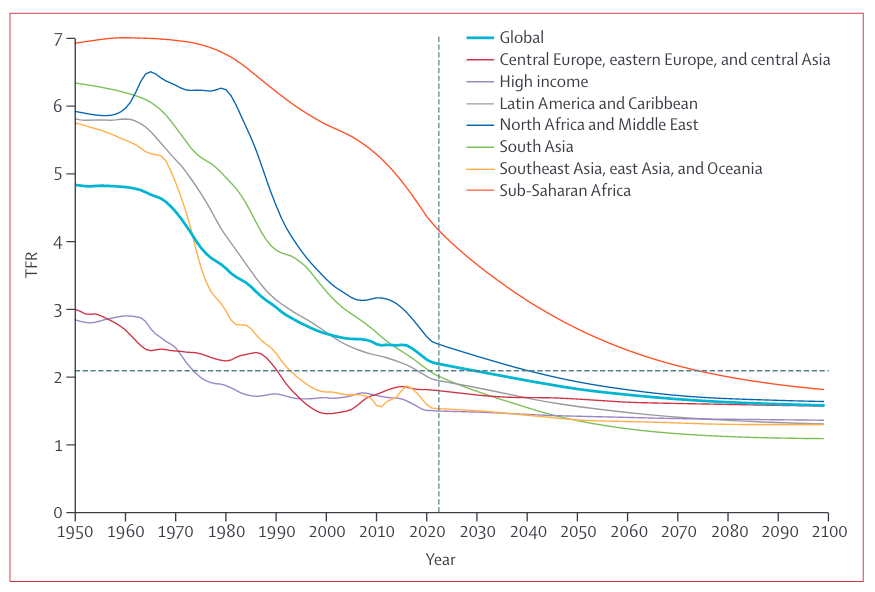

Birth rates across the developed world have fallen well below replacement levels and are not projected to rise or rebound in any meaningful way in the future. This means ageing societies, mounting fiscal strain, and, for many countries, shrinking populations.

Despite these enormous social and economic stakes, few institutions are talking about the fertility collapse. In the West, the governance infrastructure to respond to it simply doesn’t exist.

This contrasts starkly with how we have responded to other long-term threats. Climate change, for example, is discussed at every level of governance, from local councils to global treaties. It has dedicated agencies, major funding streams, and entire industries devoted to mitigating its effects. Climate concerns occupy a central place in media, politics, and academia. Fertility decline, by comparison, has attracted little sustained attention and few institutions dedicate any time or money at all to solving it.

While the issue is finally beginning to draw more attention, for the past several decades it has been largely overlooked. When fertility trends do surface in mainstream discourse, those raising the alarm are often treated with suspicion or derision—fertility decline is portrayed as the concern of reactionaries or racists, rather than as a legitimate policy challenge worthy of serious engagement.

Given the way this issue has been neglected by mainstream media and institutions, it’s crucial to ask why it has taken so long for people to realise how important this is, especially since it poses such a serious long-term threat. Why were mainstream commentators, academics, policymakers, and journalists so late to this issue?

I would argue that the lack of widespread engagement with this topic is no accident—it is the product of three intersecting forces: societal structures that obscure demographic trends, knowledge-producing institutions warped by ideological blind spots, and social norms that make fertility a fraught, even taboo, subject.

Part of the confusion stems from a simple but powerful illusion: the global population is still growing. If we were truly facing a crisis, wouldn’t we see it in the numbers?

But this is where conventional intuition misleads. The world’s population continues to rise not because we have healthy fertility rates, but because of demographic momentum—past generations were large, and their children are still moving through the system. Think of it like a rocket. Even after its engines cut out, a rocket continues to rise on the strength of its existing momentum. But the trajectory inevitably slows, plateaus, then falls.