Classical Liberalism

Classical Liberalism Without Strong Gods

How open societies can meet the challenge of meaning.

In November 2023, Ayaan Hirsi Ali stunned many of her long-time admirers by announcing her conversion to Christianity. “We can’t counter Islamism with purely secular tools,” she explained. As Peter Savodnik has documented, Hirsi Ali is far from alone. This conversion trend spans figures from Jordan Peterson to tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel. Even podcaster Joe Rogan recently declared, “We need Jesus.” In February 2025, nearly 4,000 conservatives gathered at the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC) conference in London, to hear Peterson, who now openly embraces Christianity as “the reality upon which all reality depends,” Hirsi Ali, Niall Ferguson, and others making the case that liberal societies require deeper foundations than individual rights to survive.

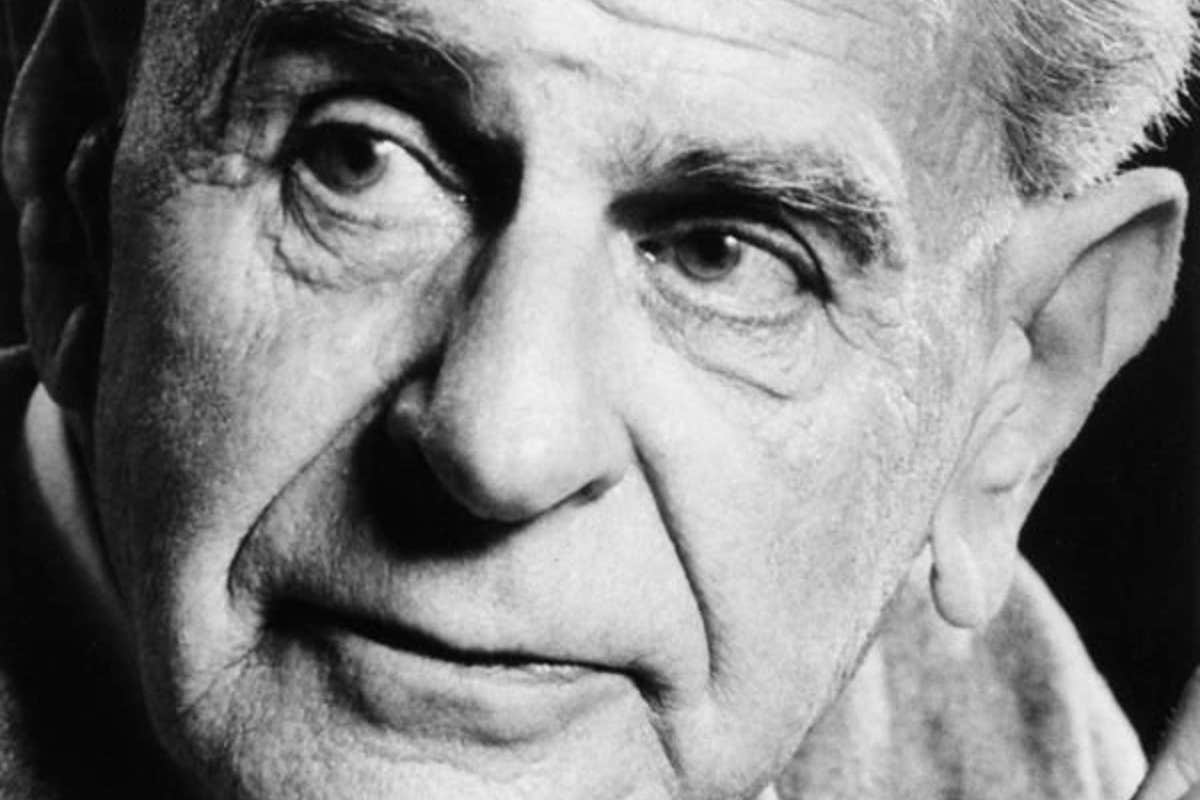

These formerly secular voices now embrace religion as a bulwark against extreme progressivism and other radical ideologies. Their views fuel a broader challenge to the foundations of postwar liberalism—especially the vision articulated by Karl Popper in his 1945 work The Open Society and Its Enemies.

In the decades since the publication of Popper’s book, the “open society” has become synonymous with the post-World War II political and moral order grounded in freedom, pluralism, and critical inquiry. Popper contrasts it with the “closed society,” in which conformity, dogma, and tribal loyalties dominate. Open societies are based on individual rights and peaceful disagreement, not on shared religious or ethnic identity. Yet in the wake of rising political polarisation, and deepening institutional distrust, many on the right now question whether such openness can still sustain cohesion or meaning.

Critics like R.R. Reno and pseudonymous essayist N.S. Lyons contend that Popperian openness offers no deeper sense of belonging or purpose. Both argue that the postwar liberal consensus dismantled traditional sources of sacred meaning—such as religion and nation—and replaced them with emotionally thin norms like tolerance and procedural openness. Both advocate a return to shared sacred commitments.

But must liberal societies choose between meaning imposed through authoritarian religious or nationalistic beliefs on the one hand and moral drift on the other? Or is there a way to preserve social cohesion without retreating to the premodern certainties the strong gods’ advocates demand?

In his 2019 book Return of the Strong Gods, Reno argues that the West’s postwar elites made a tragic overcorrection. Determined to avoid the ideological fanaticism that led to fascism and communism in the early 20th century, they embraced scepticism about all unifying ideals. This “postwar consensus,” Reno writes, “taught that strong loves—of God, of country, of truth—were inherently dangerous.” In their place, elites installed the so-called “weak gods”: tolerance, pluralism, individual rights, and economic integration. The result, he contends, is a spiritually hollow society: “Our time begs for a politics of loyalty and solidarity, not openness. We need a home. And for that, we require the return of the strong gods.”

In his 2025 essay “American Strong Gods,” Lyons argues that a social “crusade for openness” dissolved traditional bonds—faith, family, and nation—and replaced them with proceduralism and technocratic management. In his telling, the postwar liberal consensus sought not only to constrain authoritarianism but to neutralise moral conviction, weaken inherited norms, and displace thick communal identities in favour of a borderless managerial order.

In his essay “Love of a Nation,” Lyons warns that “a man cannot love a special economic zone.” Nations, like families, rely on bonds that are “covenantal, not contractual.” Without leaders who feel responsibility toward their own people and citizens who are permitted to cherish their home and feel that it is truly theirs, the liberal state becomes a hollow apparatus: efficient, but unable to command sacrifice or sustain solidarity.

This critique resonates with many for a reason. It references real phenomena: declining church attendance, an increase in mental illness, ideological fragmentation, and a general sense of drift within liberal democracies. Human beings are tribal creatures. We evolved in small communities. Our deepest intuitions are shaped by loyalty, sanctity, and shared identity. When liberal societies focus exclusively on autonomy and individual rights, they risk ignoring these foundations.

A Misdiagnosis of Where Liberal Society Has Gone Wrong

Reno accuses Karl Popper of promoting an “anti-metaphysical” order that blinds liberal societies to the moral costs of openness. Lyons likewise accuses Popper of wanting to “relativize truths,” dismantle loyalties, and replace collective purpose with technocratic neutrality. But these are caricatures of Popper’s essential thesis. The Open Society and Its Enemies is not a plea for relativism, but a defence of civilisation against dogma and authoritarianism.

Popper’s open society rests not on moral relativism but on epistemic humility: the recognition that no one holds a monopoly on truth, and that values must remain open to criticism and revision. “What we need and what we want,” he writes, “is to moralize politics, not to politicize morals.” For Popper, to “moralize politics” is to apply ethical standards to political action, while to “politicize morals” is to enshrine one moral code as unchallengeable law—a move that leads directly to political repression. Popper did not deny the existence of objective moral truths. What he denied was the state’s right to impose them as fixed certainties.

Popper’s work belongs to a liberal tradition stretching from Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill to Friedrich Hayek: thinkers who saw liberty not as amorality but as the space in which truth can be tested, errors corrected, and better ways of living discovered. As Mill insists in On Liberty, “the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth [is] produced by its collision with error.” The alternative—societies built on supposedly infallible truths—has produced gulags, gas chambers, and genocides. Liberalism is not politically restrained because it is metaphysically thin. It is politically restrained because it is morally serious.

The strong gods thesis also obscures the corrosive impact of postmodern relativism, which did more to erode shared meaning than anything Popper or Mill ever proposed. Where liberalism sees reason and open discourse as tools to pursue truth, postmodernism rejects the premise altogether. It questions whether objective truth exists, treats moral values as culturally contingent, and dismisses grand narratives of progress, liberty, or human dignity as instruments of power. “[T]ruth isn’t outside power… truth is a thing of this world,” Foucault declared. Universal values are rebranded as instruments of oppression. To many, this perspective must seem liberating. It exposes hidden power structures and challenges oppressive traditions. It promises greater freedom and inclusion. But over time, its corrosive scepticism erodes belief in shared moral foundations and social purpose.

As Allan Bloom explains in The Closing of the American Mind, when everything is relative, people no longer feel responsible for contributing meaningfully to society: “America is experienced not as a common project but as a framework within which people are only individuals, where... [the forces that gave them a sense of their place in society] have… lost their compelling force.”

Identity has increasingly filled the void left by the absence of shared cultural and moral frameworks. Religion, nationality, and even biological sex have become battlegrounds where individuals seek personal meaning. This cultural transformation began at universities, but, as Andrew Sullivan argues in his 2018 essay “We All Live on Campus Now,” it quickly spread into journalism, corporations, and government.

As postmodern scepticism gave way to identity politics, liberal norms of truth-seeking and reasoned disagreement were displaced by a new kind of moral certainty—rooted in emotional safety, identity, and lived experience rather than universal principles.Once truth was recast as power, traditional norms lost legitimacy—and so did the very idea of open disagreement. University policies on microaggressions and trigger warnings reflect a new moral framework in which harm is measured subjectively and debate can itself be construed as aggression. As Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt have observed, many students now interpret words as violence, and view disagreement as a form of disrespect or invalidation. A 2024 survey by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) found that 27 percent of US students reported feeling pressure to self-censor in class. Meanwhile, Gallup reported in 2023 that confidence in higher education had fallen to just 36 percent, down from 57 percent in 2015.

These cultural shifts were compounded by something more practical: the failure to defend the cultural and civic infrastructure that once gave openness coherence and provided moral depth. Liberal societies are now adrift not because they honoured openness too much, but because they ceased to defend the cultural and civic infrastructure that once gave that openness coherence and provided moral depth.

Visiting 19th-century America, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that much of the country’s strength lay its voluntary associations, town meetings, religious communities and other schools of public spirit. Today, this fabric is fraying—and not just in the US. As Robert Putnam noted twenty years ago in Bowling Alone, the institutions that once sustained civic life have steadily weakened since the mid-20th century. Trust in others has eroded as participation in local organisations has declined.

Bureaucratic centralisation further weakened community-level self-government by displacing local initiative. As Yuval Levin observes in The Fractured Republic, a nationalised political culture has increasingly crowded out the “middle layers” of society—the local associations that once formed the bedrock of civil life.

In the UK, local authorities now raise only a fraction of the revenue they spend, leaving them heavily dependent on central government transfers and limiting their scope for local innovation or accountability. A 2022 report by Centre for Cities concluded that Britain has become “one of the most fiscally centralised countries in the developed world.” As Philip Blond argues in Red Tory, “the state and the market have conspired to hollow out civil society, leaving individuals atomised and communities fragmented.”

Schools have also retreated from their traditional role of transmitting shared civic knowledge. Curricula have shifted toward identity, wellbeing, and emotional literacy—often at the expense of historical understanding or constitutional reasoning. The result has been a generation often unable to explain the institutions that protect their freedoms or the norms that sustain public life. In Australia, the latest National Assessment Program – Civics and Citizenship (NAP-CC) revealed that only 28 percent of Year 10 students met the proficient standard in 2024, a decline from 38 percent in 2019. The 2023 Annenberg Constitution Day Civics Survey found that only 66 percent of US adults could name all three branches of government. This is worrying because civic education teaches young people how to participate in a pluralistic democracy, how to resolve disagreement peacefully, and why liberal institutions matter. It provides a shared vocabulary about the common good without requiring a shared theology or ethnicity. As E.D. Hirsch warns in Cultural Literacy, civic enfranchisement depends on a shared base of knowledge. Without it, democratic deliberation breaks down.

The erosion has also been cultural. As Charles Murray documents in Coming Apart, the breakdown of marriage, workforce participation, and civic engagement among the American working class is not simply the result of economic changes. Welfare systems frequently discourage family formation. The US and UK have both imposed penalties on marriage—reducing benefits when low-income couples formalise their relationships. Meanwhile, tax systems in Australia and the UK often favour dual-income households while undervaluing unpaid caregiving, placing single-earner or stay-at-home parent families at a disadvantage. As with so many liberal failures, the outcome was not intentional. It emerged from neglect: no one meant to punish families, but the effect has been to erode them.

More serious still are the failures in school education and housing—one a domain the state has largely assumed responsibility for, the other shaped by state-imposed constraints that have distorted supply and affordability. When families are priced out of housing or trapped in failing schools, disillusionment grows—not because people have rejected liberal values, but because they no longer believe the system works.

Take housing. Median house prices in Sydney now exceed ten times median income. In the US, nearly half of renters spend more than thirty percent of their income on rent, and nearly one in four spends over fifty percent. The causes are well known: restrictive zoning, NIMBYism, and planning regimes that constrain supply. A system that delivers unaffordable homes, failing schools, stagnating wages, and/or inaccessible healthcare will struggle to command loyalty—no matter how well it performs in abstract indices of freedom.

The leading figures of the strong gods movement are critical of the open society but they have no clear plan for replacing it. Reno seeks a revival of Christian orthodoxy. Ayaan Hirsi Ali wants a civilisational defence against Islamism. Peter Thiel blends cultural Christianity with technological futurism. Niall Ferguson oscillates between admiration for national tradition and discomfort with populist excess. Joe Rogan offers a folk-theological yearning for rootedness. What unites them is not a coherent philosophy but a shared anxiety about liberal drift.

As James R. Rogers has pointed out, this internal incoherence is the movement’s Achilles’ heel. Specific appeals to thick religious or national identity will alienate many people within pluralistic societies; vague gestures toward transcendence lack emotional power. The result is a contradiction: to inspire unity, the gods must exclude; to preserve peace, they must be diluted. Either way, the project fails on its own terms.

Worse, when the strong gods do consolidate political power, the consequences are often authoritarian. Gods, once enthroned, rarely stay within democratic bounds. In Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s blend of Islamic revival and nationalist pride has steadily eroded judicial independence and press freedom. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s “illiberal democracy,” built explicitly on appeals to Christian heritage, has marginalised minorities. Donald Trump has been following a similar path, embracing religious and nationalist rhetoric as cover for undermining constitutional norms. He increasingly casts political opponents as enemies of God and country. As Peter Wehner has warned, Trump’s “appetite for revenge” threatens to turn democratic institutions into tools of sectarian punishment.

So, What are Liberal Societies to Do?

The model Tocqueville observed in 19th-century America still works. The evidence is particularly striking in Denmark. Denmark consistently ranks among the world’s most cohesive and high-trust democracies. It places near the top of both the OECD’s Better Life Index and the World Happiness Report, scoring highly for life satisfaction, trust in government, and civic engagement. Around 74 percent of Danes say most people can be trusted. According to Danish political scientists Gunnar Lind Haase Svendsen and Gert Tinggaard Svendsen, this trust translates into an approximately 25 percent increase in Denmark’s national wealth, thanks to reduced transaction costs and lower bureaucratic overheads.

This trust is not rooted in religious uniformity: Denmark is one of the world’s most secular countries and increasingly diverse. Its cohesion stems instead from strong civic networks, supported by public institutions that are transparent, responsive, and widely trusted. In Denmark, social cohesion has persisted alongside secularisation, not in opposition to it. This social cohesion is built through civic structures. More than 100,000 associations—spanning everything from volunteer fire brigades and choirs to hobby clubs and trade groups—serve a population of just 5.7 million. Most Danes belong to several over their lifetimes.

Liberal societies might benefit from what political theorist Dolf Sternberger has called “constitutional patriotism.” Rather than binding citizens through shared ancestry, religion, or ethnic identity, this form of belonging is rooted in a shared commitment to liberal principles such as equality before the law, freedom of conscience, and democratic governance. Sternberger argues that over time, citizens can come to emotionally identify with: “a new, second patriotism … founded upon the constitution.”

This patriotism must be taught, however. In Cultural Literacy, Hirsch warns that when schools fail to transmit a common base of knowledge, “it would be hard to invent a more effective recipe for cultural fragmentation.” Universities also play a crucial role in civic formation. Yet many have abandoned this responsibility. As I have argued elsewhere, there is much governments can lawfully do to nudge state-funded universities towards preparing citizens for democratic life. Most importantly, they must foster reasoned disagreement, intellectual openness, and a commitment to truth that transcends partisan boundaries.

Liberal societies also need emotive civic rituals and public symbols. Events like Australia’s Anzac Day or the US Fourth of July are powerful precisely because they express a collective national purpose and unite people through shared historical and cultural rituals—rather than shared ancestry or religious belief. Nations need stories they can tell about themselves that are forward-looking, inclusive, and cohesive. A society paralysed by shame will not survive. Nor will one built on nostalgia. Research by More in Common has found that Americans still converge around core historical symbols, heroes, and holidays—suggesting that shared civic narratives remain a key source of unity, even across partisan divides.

Sport plays a similar role. When Australia plays a cricket Test match, or America pauses for the Super Bowl, civic fractures are momentarily bridged. These moments may be fleeting, but they point to something enduring: the human hunger for collective striving, and for rituals that affirm shared belonging without requiring ideological consensus. A recent survey found that ninety percent of Americans believe sport brings people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds together—making it one of the few arenas of widespread agreement. Liberal democracies should cherish sport and resist its politicisation. It is one of the few remaining sites of spontaneous national unity.

Constitutional patriotism, then, can live in story, education, ritual, and shared public life. In this way, liberal democracies can foster cohesion without succumbing to the exclusionary certainties of the strong gods.

Liberal societies should also recover the civic power of local communities. Excessive centralisation has weakened the “middle layers” of society—displacing voluntary institutions and disempowering citizens. One remedy is subsidiarity: shifting decision-making closer to those affected by it. Switzerland exemplifies this, with a federal system that gives substantial autonomy to cantons and communes and engages citizens directly through referenda. Denmark, too, maintains high levels of civic trust in part because of its strong municipal governance, which fosters responsiveness and local accountability. These decentralised models offer a way to restore civic belonging without resorting to top-down cultural unity.

Liberal societies also need clear moral and civic boundaries. Mutual tolerance should not be a suicide pact. A society committed to free expression, freedom of religion, and equal treatment must also be willing to defend those norms against ideologies that seek to dismantle them. Immigration can enrich liberal societies—but only if newcomers accept core liberal principles.

Denmark offers a compelling example. Immigrants are expected to learn Danish, participate in civic education, and affirm democratic norms. These are not ideological loyalty tests but civic guardrails—basic commitments that make pluralism possible. New citizens must sign a Declaration on Integration and Active Citizenship, pledging support for gender equality, freedom of expression, and mutual respect.

As Douglas Murray has argued, Western states have too often feared articulating their values lest they sound exclusionary. But inclusion requires clarity. The price of admission to a liberal democracy should be respect for the rules that make peaceful coexistence possible. That includes rejecting efforts—from any quarter—to impose religious orthodoxy, racial essentialism, or ideological loyalty tests. Liberal societies need to rediscover the confidence to say not only what they stand for, but what they will not tolerate: forced conformity, political violence, and illiberal creeds that reject mutual respect. Clearer legal boundaries may be needed. But if governments, civil society leaders, and educators are willing to name liberal values explicitly and to defend them without apology, this moral clarity may be enough.

Liberal societies should also confront the policy failures that have made the promise of freedom feel increasingly out of reach. When younger generations cannot afford homes, start families, or progress in their careers, who could blame them if they begin to drift toward nihilism? Education, housing, health, and welfare are all critical to the good life—yet all show signs of acute failure. But better outcomes are possible.

Tokyo has maintained housing affordability by allowing density and minimising zoning restrictions. Charter schools like Arizona’s Great Hearts Academies have allowed diverse communities to access excellent education. The 1996 US welfare reforms, which tied support to work, led to sharp reductions in dependency and child poverty, especially among single mothers. In the decades since, the political will to sustain these reforms has weakened and they have been eroded. Still, the episode reminds us that it is possible for the state to expand opportunities and provide help without perpetuating dependence.

Liberalism must deliver the conditions for flourishing: security, opportunity, and a path upward for those willing to take it. This does not necessarily mean more government, but it does mean that we need government that works and systems that reward effort, protect dignity, and enable self-reliance.

Liberal societies cannot restore family life by decree, nor should they try. But they should stop undermining it. They can remove the welfare systems that penalise marriage and tax codes that undervalue caregiving. Families do not need strong gods. But they do need societies that stop punishing those who try to build something lasting.

Most importantly, liberalism needs to reclaim its moral ambition. It has too often ceded the language of meaning to its critics. In doing so, it has come to be seen as technocratic and rootless—more focused on process than purpose, more fluent in rights than in the common good. Meanwhile, as elites have drifted leftwards toward relativism or identity-based theory, they have actively disavowed the institutions they inherited. Into this vacuum have stepped challengers—from religious nationalists to populist authoritarians—who promise strength without principle and belonging without liberty.

Yet liberalism at its best is not morally indifferent. It is a tradition that believes dignity is discovered through freedom, character is formed in voluntary association, and solidarity is built through reciprocity, not coercion. The current turn toward strong gods reflects a fear that open societies can no longer provide meaning. That fear is misplaced. Liberal societies need not imitate sacred authority to inspire belonging. But they must stop outsourcing meaning to the very forces that threaten them. The open society will only endure if it is made into something people can believe in again—because it delivers not just rights, but prosperity; not just institutions, but ideals worth committing to. The real test is not whether liberalism should resurrect the religious or nationalist certainties of the past, but whether it can rebuild the civic and cultural foundations that allow meaning and freedom to flourish together.

Erratum: In an earlier version of this article, the author’s paraphrase in the sentence that follows was erroneously presented as a direct quotation: “As Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt have observed, many students now interpret words as violence, and view disagreement as a form of disrespect or invalidation.”