Art and Culture

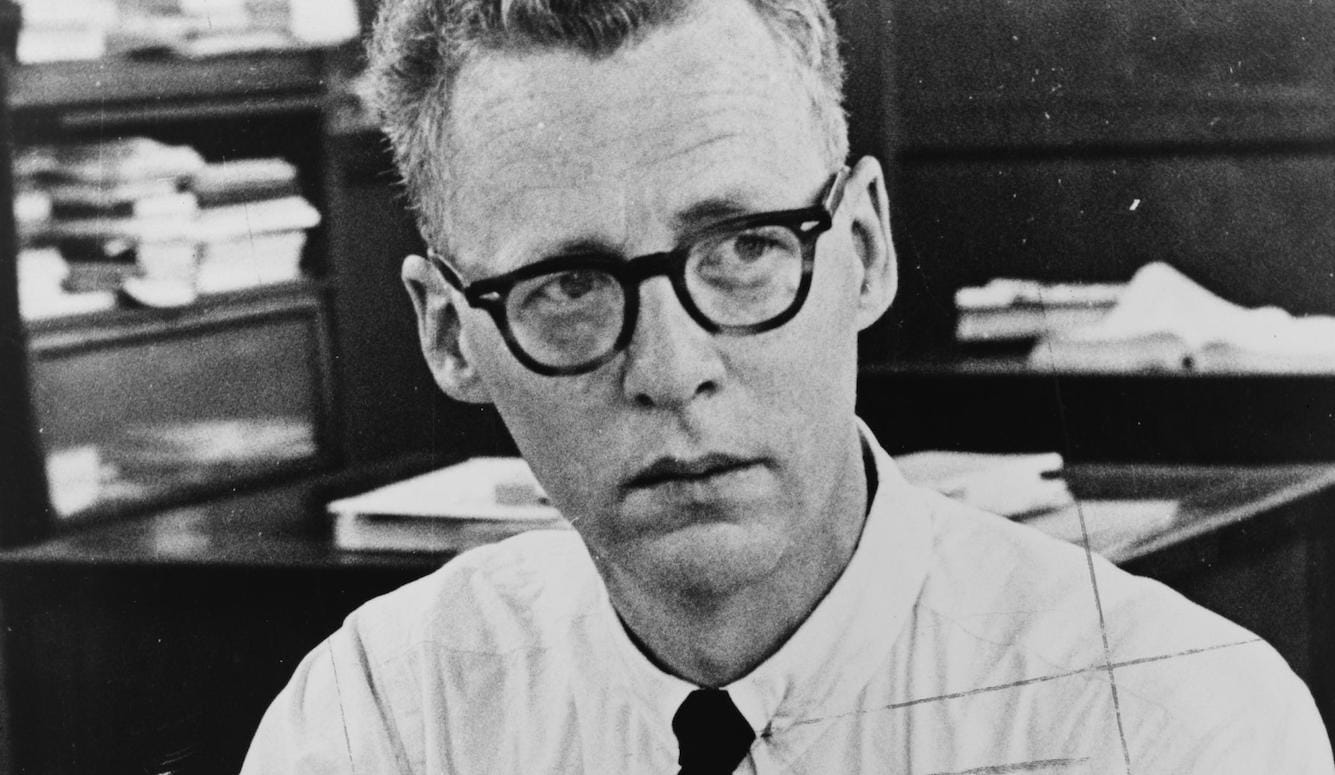

Heterodox Radical

A new collection of Murray Kempton’s articles reveals a thoughtful journalist whose politics were difficult to categorise.

A review of Going Around: Selected Journalism by Murray Kempton, edited by Andrew Holter; Seven Stories (April 2025).

During an interview towards the end of his life, journalist Murray Kempton was asked by C-Span’s Brian Lamb how he defined himself politically. Kempton burbled on a bit about “Tory anarchism” (to this day, I don’t know what that is) before finally settling on “radical.” Lamb didn’t press the point so it was left to posterity to decide, but a new collection of Kempton’s journalism from 1935 to 1997 confirms that his politics were difficult to categorise.

If “radical” is assumed to be a synonym for far-Left, then it isn’t really apt—Kempton was too broad-minded and unpredictable for that. He was a repository of second thoughts, and of following the evidence where it led, even if it ended up contradicting his previous position. He was a defender of underdogs (his favourite adage was “never kick a man except when he is up”), and fond of reminding his readers that there was always another side to every story, an uncomfortable fact that challenged even the most sympathetic of portraits. And all of this came from a person whose ancestor, Senator James Murray Mason, drafted the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which pledged federal assistance to forcibly return escaped slaves to their owners.

James Murray Kempton (1917–97) was born in Baltimore into what he liked to call “shabby gentility.” This meant that his family had servants but his mother worked and they had no car. Or as he put it:

The world of shabby gentility is like no other; its sacrifices have less logic, its standards are harsher, its relation to reality is dimmer than comfortable property or plain poverty can understand.

Kempton’s interest in journalism was sparked by living in the same town as America’s most famous journalist, H.L. Mencken. While working as a copy boy at the 1936 Democratic Convention in Philadelphia, he even managed to exchange a few words with his idol. Kempton would remember seeing Mencken in the pressbox in rhapsodic terms: “[He was] weaving gold from the straw of the podium discourse while journalists at leisure craned over his shoulder to watch his next marvel clatter forth.” Years later, Kempton would describe his coverage of political conventions in a manner that could have come from Mencken’s typewriter: “[A political convention] is not a place from which you can come away with any trace of faith in human nature.”

In 1935, Kempton left the Confederacy-haunted area of his upbringing for the other side of town when he enrolled at Johns Hopkins University—an institution that, like other elite colleges in the mid-to-late 1930s, had a student body that leaned left. Until then, the Party line had been that capitalism was finished and that hope lay in Moscow communism. But now, it was that patriotism and communism could co-exist: “Communism is 20th century Americanism,” proclaimed Communist Party leader Earl Browder. Liberals, socialists, and communists were encouraged to link arms.

Kempton was affected by this political atmosphere, and he joined the Young Communist League during his freshman year, around the time he began writing for the student paper, the Johns Hopkins News-Letter. Kempton recalled his time in the League with humour: “I was the first campus radical who wasn’t Jewish. Therefore I wasn’t taken very seriously.” Nevertheless, he became a dedicated organiser for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and a pamphleteer for the Party.

Being a Party member brought prestige and a kind of political affirmative action. As a result of his politics, Kempton became editor-in-chief of the student newspaper. From the vantage point of the anti-communist 1950s, he later marvelled, “There was a time in this country when you joined the Communist Party to advance your career.” He recalled those years as a time when he wrote with “windy preachment,” but even then he was canny enough to see that Stalin’s 1934–38 show trials were a monstrous frame-up. He left the Communist Party for Norman Thomas’s Socialist Party, a left-wing but anti-Stalinist movement.

After graduating, Kempton worked as a labour reporter for the New York Post. This was interrupted by service in the Army Air Corp during World War II, and he was stationed in New Guinea and the Philippines. By now, he had shed any leftwing idealism about the antifascist struggle (“a kind of silly, utopian, revolutionary view of the war”). He saw some combat and would have been killed had a bullet not been deflected from his chest by a cartridge clip. (During the Vietnam War, he became disgusted by those privileged enough to use college deferment to avoid the draft while working-class Americans were made to fight.)

After the war, Kempton resumed his labour reporting for the New York Post under the tutelage of anti-New Deal reporter Victor Riesel. Watching Riesel turn purple whenever he spoke about liberals caused Kempton to become a soberer reporter: “If anger becomes your technique,” he remarked, “in the end you find there’s nothing in you but rage.” He later wrote for Newsday, edited the New Republic in the 1960s, and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985. His 1955 book, Part of Our Time, documented his growing disenchantment with 1930s communism. The Communist Party, he eventually concluded, “had no room in it for doubt or pity or mercy,” and this lesson became central to Kempton’s journalism thereafter.

Much of Kempton’s writing collected in Going Around is an attempt to practise the qualities that the Communist Party had so conspicuously lacked. That is why he is so difficult to pin down politically, no matter what the era and no matter what he called himself. Doubt and pity and mercy are not always fashionable, and this often put him at odds with liberals. Upon Richard Nixon’s death in 1994, Kempton chastised liberals who grudgingly praised the former president for opening diplomatic relations with Red China. “The liberals,” he wrote, “have once again missed the point. Nearly a generation has gone by with few signs of Nixon’s China policy making a discernible difference in the world.”

Those liberals who numbered Kempton as one of their own also missed the point, for Kempton sometimes had kind words to say about liberals’ foes that they didn’t possess the generosity to utter. Of the disgraced Nixon being denied a Manhattan apartment because the residents didn’t want such a noxious neighbour he wrote: “Who else in America except the tenant of an East Side co-op has a license to lock somebody out for no better reason than his fancied unlikeability?” Kempton even found something praiseworthy about G. Gordon Liddy, a Watergate burglar who once offered to be assassinated for Nixon. He admired Liddy for accepting jail time rather than naming those involved in his black-bag operations: “Liddy can be to the market in honor what McDonald’s is to hamburgers,” he wrote.

Kempton took issue with jeering liberals who dismissed ex-President Eisenhower as an airhead. He believed that Eisenhower’s “stupidity” was a mask: “He was the great tortoise upon whose back the world sat for eight years. We laughed at him; we talked wistfully about moving; and all the while we never knew the cunning beneath the shell.” But he saw more than cunning in Ike. There were, he wrote, “sovereign virtues to his detachment.” Unlike liberals, who believed that America would have been spared the agony of Vietnam had JFK dodged Oswald’s bullets, Kempton saw that the war could only have been avoided if Ike had been permitted to serve a third term as president.

And there was, in fact, some evidence for this counterfactual. In 1954, Ike had stubbornly refused to provide the French imperialists with military aid to fight Ho Chi Minh, despite pleas from his inner circle and from the French themselves. Kempton noted with approval that Eisenhower had predicted that committing America militarily to Vietnam would be a debacle. In his memoirs, Eisenhower reported that, during an April 1954 NSC meeting to discuss intervention, “I remarked that if the United States were, unilaterally, to permit its forces to be drawn into conflict in Indochina, and in a succession of Asian wars, the end result would be to drain off our resources and to weaken our overall defensive position.” Therefore, Kempton concluded, “Vietnam was a liberal’s war and liberals bore responsibility for it.”

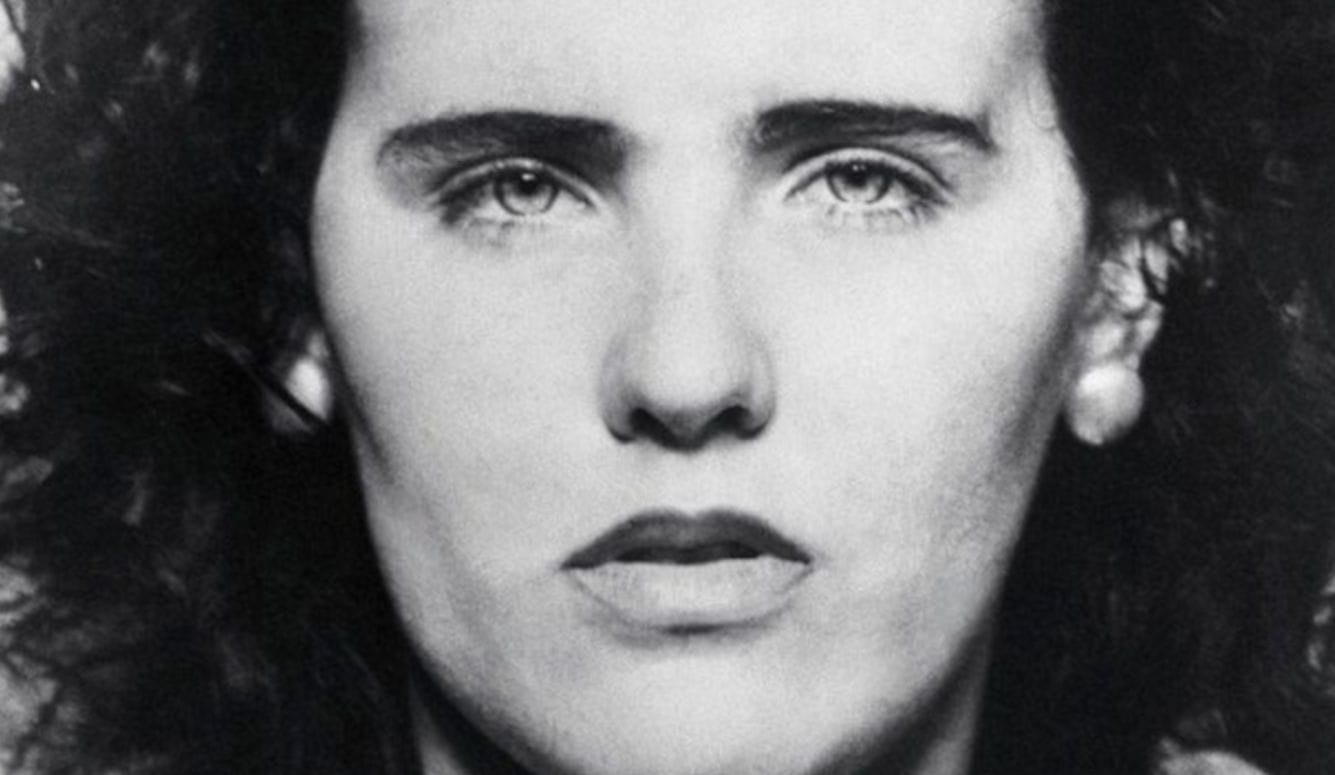

Kempton was never comfortable with the label of “anti-communist” (he preferred the term “nationalist”). He spoke at meetings of the American Veterans of the Spanish Civil War and always reminded people that those who refused to “name names” did so in accordance with their Americanism rather than Communist Party discipline. But he nevertheless did have an anti-communist side. He accepted that Alger Hiss and the atom spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were guilty as charged. He described the married couple’s prison letters as a “dehumanized mess of leftwing gook,” but he wanted their death sentence reduced to life imprisonment.

Kempton admired the stand that the communist and mystery writer Dashiell Hammett took in refusing to give the American government the names of the Civil Rights Congress. But he also reminded his readers of how Hammett and that communist front group had “voted to refuse its support to the cause of James Kutcher, a paraplegic veteran who had been discharged as a government clerical worker because he belonged to the Trotskyist Socialist Workers’ Party.” Trotskyites, Kempton reminded his readers, were anathema to Stalinists like Hammett and Paul Robeson, who bellowed to the Party faithful that defending Kutcher was like asking “Jews to help a Nazi.”

Reviewing Lillian Hellman’s 1976 memoir Scoundrel Time during the high tide of her cultural rehabilitation (she received a standing ovation at the Academy Awards), Kempton lauded her “principled” refusal to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. And yet he also detected something nasty beneath the glamour. She was, he decided, a “bully” who “is inclined to be a hanging judge of the motives of persons whose opinions differ from her own.”

Reflecting on his career at seventy, Kempton said:

I have seen Robert Kennedy with his children and John Kennedy with the nuns whose fidelity to their eternal wedlock to Christ he strained as no other mortal man could. I have been lied to by Joe McCarthy and heard Roy Cohn lie to himself and watched a narcotics hit man weep when the jury pronounced Nicky Barnes guilty. Dwight D. Eisenhower once bawled me out by the numbers, and Richard Nixon once did the unmerited kindness of thanking me for being so old and valued an adviser.

But perhaps a better summary of his approach to journalism was provided by this description of his method of operation in his New York Times obituary:

On Nov. 21 last year, at a Society of the Silurians dinner honoring him, Mr. Kempton recalled his early days as a labor reporter. The first year he received 150 bottles of “reasonably good” whisky for Christmas, the normal ration for the reporter on that beat. The second year he got two.

“I realized for the first time that meant that I would never in the future have any sources, and I could henceforth be an outsider, and I was simply stuck with watching the game and ending up most of the time in the lonely honor of the loser’s dressing room.” It was, he made clear to his audience that night, where he preferred to be.

That is why Murray Kempton would not fit into today’s journalism—he was not interested in taking sides in a team sport or flattering his sources or currying favour with those who might advance his career, he was interested in providing his readers with a truthful analysis of the facts as he saw them. In today’s world of sixty-second pundits and fiercely competitive zero-sum tribalism, there is very little room for Kempton’s brand of honesty, mercy, and second thoughts. More’s the pity.