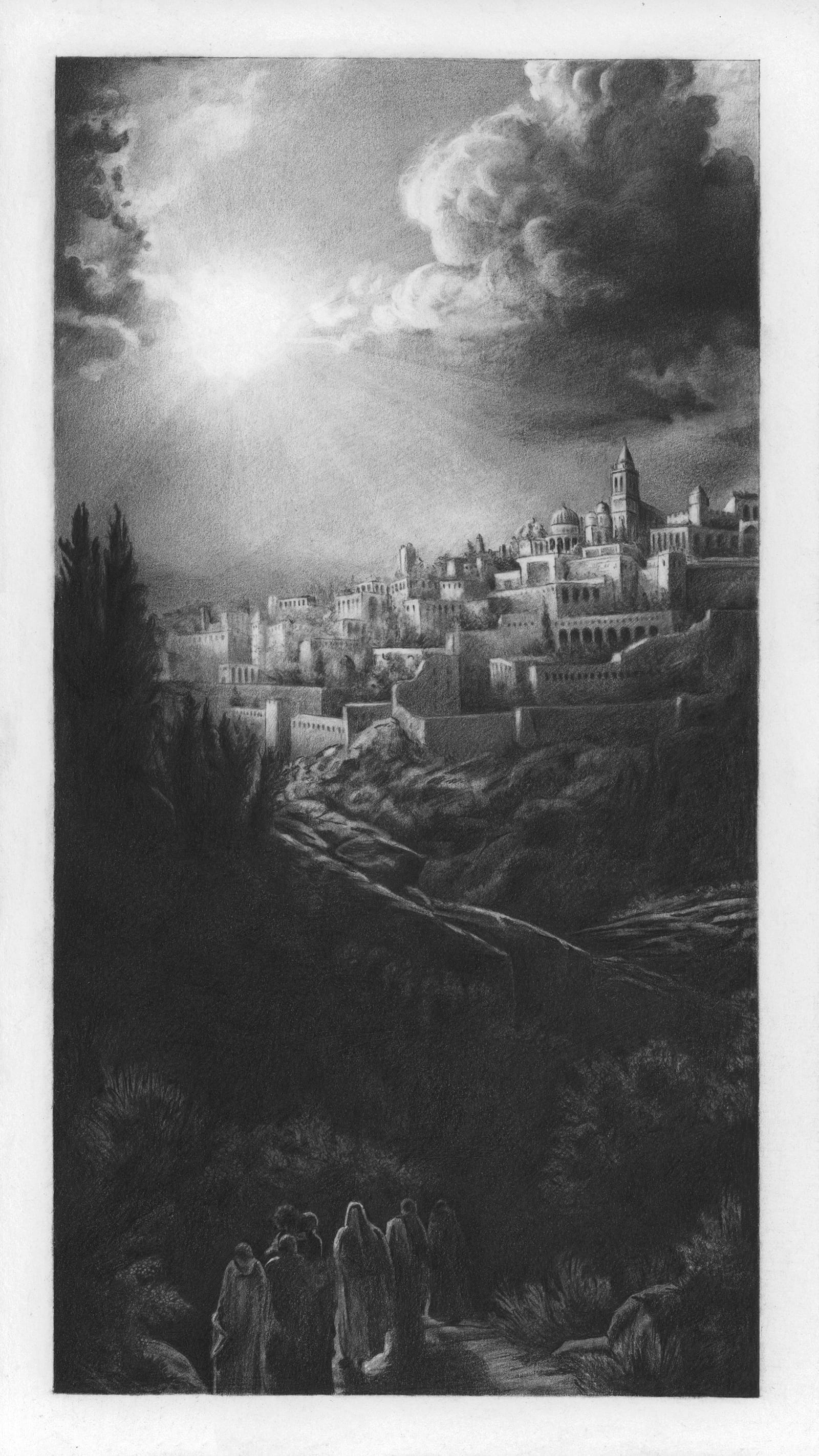

For almost 300 years, America has cultivated the metaphor of a shining city on a hill to describe how a righteous society is a beacon for a better life—but the same light casts that city under a glare, exposing its defects. The image comes from Jesus speaking to his followers in the Book of Matthew (5:14), “You are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hidden.” When the Puritans departed England for Boston in 1630, their leader John Winthrop used the metaphor to warn them that “the eyes of all people are upon us,” as they set forth to establish a new community.

Two hundred years later, when Alexis de Tocqueville chronicled American democracy in the 1830s, he asserted that these early colonists “brought to the New World a Christianity that I cannot depict better than to call it democratic and republican,” for “[n]ext to each religion is a political opinion that is joined to it by affinity.” Twentieth-century American presidents like John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and Barack Obama made a habit of referencing the shining city in speeches, especially when visiting Massachusetts, to define America as a lighthouse for liberalism. In Australia, the variation “the light on the hill” was used in a 1949 speech by Prime Minister Ben Chifley.

The image of a shining city on a hill encapsulates the optimistic vision that free, open societies will thrive and spread as the world converts to liberal democracy. But it comes with a warning: The same torch that beckons the huddled masses toward Lady Liberty also illuminates the shame of liberal democracies that betray their values. Because the light symbolises righteousness, every failing is an indication of hypocrisy. And like women inspecting their pores under the cool glow of LED-rimmed mirrors, each blemish can make citizens of liberal democracies more neurotic—while clever dictators shroud themselves in mood lighting.

If the story of the twentieth century was that of liberalism overcoming totalitarianism, then the question facing the twenty-first century is whether that win is durable. Liberalism likely needs the self-esteem expressed in a belief that it is a shining city on a hill to withstand whataboutism from its repressive and violent competitors. Its people need to fix problems rather than fixate on them, so that when citizens of liberal democracies feel as though they’re standing under harsh fluorescents, it is because they are like surgeons stitching wounds—not pathologists conducting autopsies.

Admittedly, right now it feels as if the American-led liberal order is haemorrhaging on the operating table. It has been compromised by President Donald Trump curtailing alliances and trade with nearly every other liberal democracy—except perhaps one. “Publicly, Benjamin Netanyahu and his supporters continue to paint Trump as a staunch, irreproachable supporter of Israel,” wrote the Israeli historian Benny Morris for Quillette last month:

They point to the fact that, during his first term as president, he transferred the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, as Israel had long demanded, and remind people that he helped facilitate the Abraham Accords of the early 2020s, which normalised the Jewish State’s relations with Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, and even Sudan. And in recent weeks, he revoked his predecessor Joe Biden’s suspension of certain weapons shipments to Israel, including 2,000-pound (907 kg) aerial bombs and 155 mm artillery shells.

But serious doubts remain as to Trump’s commitment to the “special relationship” between Washington and Jerusalem, especially in view of his apparent abandonment of Ukraine and his very public efforts to distance the United States from its traditional commitments to European security.

Morris explains that the special relationship is “based on shared values like support for democracy” and that it “predates even the establishment of Israel itself in May 1948.” From the American perspective, many people understand the very existence of Israel as a consequence of the twentieth-century battle between liberalism and totalitarianism, and they learn about Israeli history as a sequel to the Holocaust story. More broadly, citizens from all countries that once liberated Nazi concentration camps have incorporated their grandfathers’ heroism into their national identities so that the outcome of the Holocaust story is pivotal to how people in all liberal democracies think of themselves.

This includes Israelis. For David Ben-Gurion, the “founding father” and first prime minister of Israel, the Jewish State was meant to be “a light unto the nations.” This formulation comes from the book of Isaiah (49:6), “I will also make you a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.”

W.E.B. Du Bois saw Israel’s potential and urged his fellow Americans to help the aspiring country, writing that it was “not a difficult question.” He became an early supporter of Israel after he saw the flattened Warsaw ghetto. It taught him that his previous framework for understanding race relations had been provincial, restricted as it was to conflicts between black and white. He writes: