Art and Culture

All Men Behaving Badly

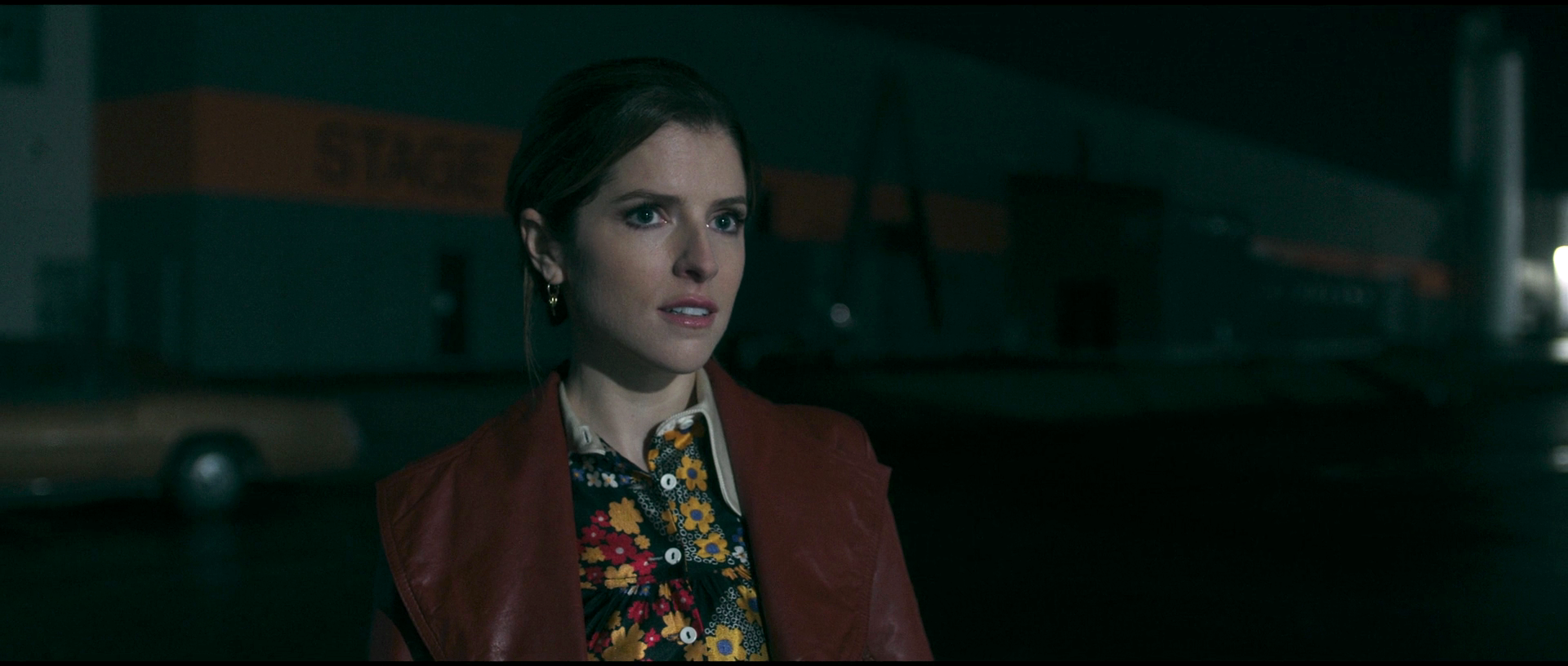

Just six months after it was released by Netflix, Anna Kendrick’s feminist film about a real serial killer already looks like an ideological relic.

I.

Anna Kendrick’s directorial debut Woman of the Hour premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in September 2023 and was released by Netflix in October 2024. It ought to have been a compelling story—a fictionalised account of a real-life vetting snafu that allowed a serial killer named Rodney Alcala to be booked as a bachelor contestant on The Dating Game television show in 1978. But Kendrick has given the narrative some 21st-century feminist topspin, evidently intended to capitalise on the extremely recent #MeToo and #BelieveWomen zeitgeist. Six months after it appeared, her film already looks like an ideological relic.

Kendrick plays Sheryl Bradshaw, a version of real-life Dating Game participant Cheryl Bradshaw, who picked Alcala as her date but found something off-putting about his vibes and never went out with him. Kendrick and screenwriter Ian McDonald present their fleshed-out version of this episode as a study in pervasive misogyny that extends far beyond Alcala’s lethal obsessions and into the realm of the “societal” and the “systemic.” It is the only movie I have ever seen in which every male character we meet or even hear about turns out to be a dangerous creep or a predatory sleaze or an insensitive sexist jerk of some kind. In Kendrick’s universe, the psychopath is not a categorically different kind of man but just a more extreme instance of omnipresent sexually aggressive and threatening male behaviour.

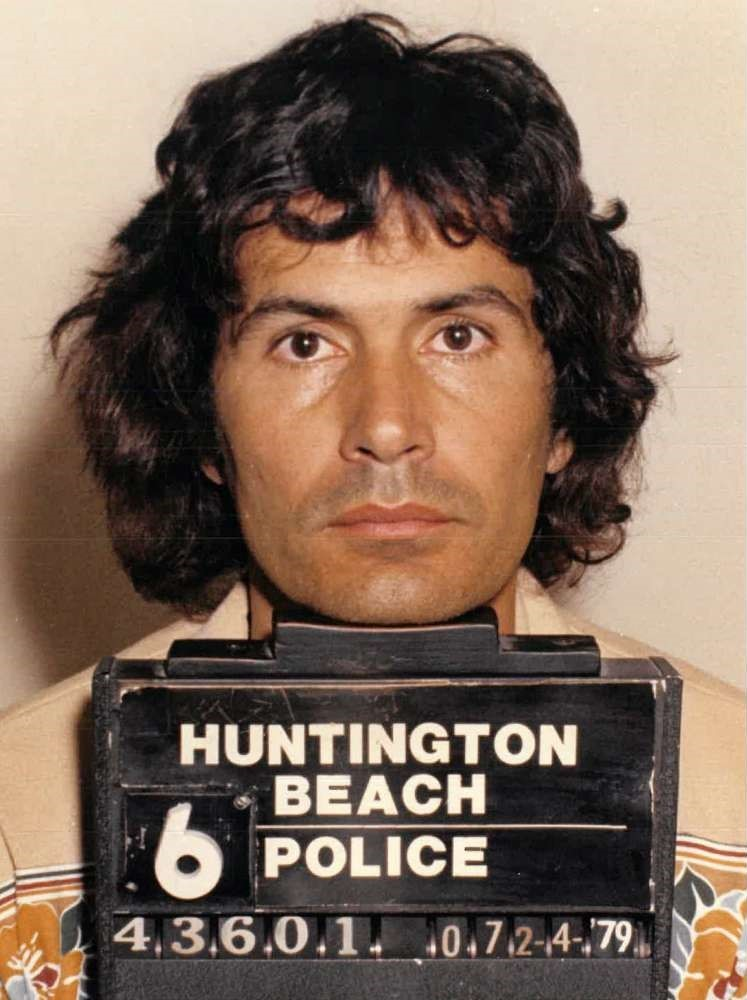

The real-life Rodney Alcala died of a heart attack in a Californian prison in 2021 aged 77, having dodged a death sentence imposed for seven murders he committed in the state between 1977 and 1979. (He was also convicted of two murders in the state of New York, and has been linked via DNA testing and recently discovered evidence to more than a hundred other homicides.) One of the California murders was committed less than three months before his Dating Game appearance on 13 September 1978.

All of Alcala’s crimes had sexual overtones; he either raped his victims before he killed them or molested their corpses afterwards. Sometimes he would strangle them into unconsciousness and then revive them just so he could strangle them again. These young women and girls were often young hitchhikers he picked up and lured with the promise that he could help them launch modelling careers by taking publicity shots for them. And he was not untalented with a camera; he was a UCLA arts graduate and had attended NYU’s film school, where he claimed to have studied with Roman Polanski. He liked to show off his portfolio of hundreds of photographs, which included stills of naked underage girls (and some boys) whose mothers, he said, had given him permission.

Alcala committed his first recorded sex crime in 1968, raping an eight-year-old West Hollywood girl and beating her badly enough to put her into a coma for 32 days. Before his arrest for that crime, he eluded the police and his parole officer by fleeing to New York where he lived under an assumed name. He was apprehended three years later in New Hampshire, after someone recognised his face from an FBI “Most Wanted” photo, and extradited to California. However, the girl’s parents refused to let her testify, and Alcala ended up with a three-year prison sentence for the lesser offence of child molestation. He was paroled in 1974 and required to register as a sex offender.

Less than two months later, Alcala was re-arrested for assaulting a thirteen-year-old girl, served two additional years, and was out on parole again by 1977. He committed his first California murder that November. That such an obviously dangerous man was allowed to remain at large for so long clearly indicates a litany of failures on the part of law enforcement and the judicial systems in at least two states. It should be remembered, though, that cross-country police-communications infrastructure was still fairly primitive half a century ago, and there was no such thing as DNA testing. As for The Dating Game’s negligent booking of a two-time felon and registered sex offender, its executives were lucky that Cheryl Bradshaw decided Alcala was too “creepy” (in her own words) to spend time with.

In Woman of the Hour, Cheryl/Sheryl Bradshaw’s story is interwoven with heavily fictionalised (but quite plausible) reconstructions of three of Alcala’s other murders, presented in non-chronological order. In June 1977, Alcala picks up Sarah (Kelley Jakie) while she is hitchhiking, drives her to the Wyoming badlands, and strangles her (the body of her real-life counterpart wasn’t found until 1982 and wasn’t identified until 2015, when Alcala was too sick to stand trial). In June 1971, he murders an airline stewardess named Charlie (Kathryn Gallagher) after she invites him off the street to help her carry furniture up to her New York apartment after the men from the moving company refuse. And in December 1977, he murders Alison (Cody Heller) on the Malibu beach.

In the film, Alcala’s final victim is Amy (Autumn Best), a teenage runaway whom he rapes and tries to strangle in the California desert in February 1979. Amy survives the attack and manages to call the police, who finally arrest him. But in real life, that wasn’t quite the end of Alcala’s criminal career. His mother bailed him out of jail and he managed to commit two more murders before his parole officer caught up with him in July 1979 and he was put behind bars for good.

Alcala is played by horror-film veteran Daniel Zovatto with an appropriately harrowing combination of moon face, Jesus hair, and oily ingratiation that turns to nastiness on a dime. Mostly, though, Woman of the Hour is about all men behaving badly. Sheryl, we learn, is an aspiring actress unable to get a break and shocked to discover that the intellectual climate in 1970s Hollywood is not at all like that of Columbia, where she got her master’s degree in acting. She goes to an audition where the (male) casting directors crack a risqué joke and ask if she’s “okay with nudity.” Her best friend makes unwelcome passes at her as he tries to hoist her out of the friend zone. Her agent, Helen (Jessica Chaffin), offers her a slot on The Dating Game telling her that she’ll be “seen” (a thinly disguised reference to the “male gaze”) and that the suitably classy Sally Field got her start on the show. Sheryl considers the show to be beneath her but reluctantly accepts in the absence of other options.

The format of The Dating Game requires Sheryl to choose a date from three hidden bachelors on the basis of the answers they give to the scripted questions she asks each of them. The prize for both will be a theoretically glamorous date subsidised by the studio. The show’s host, Ed Burke (Tony Hale), is a greasy, sideburned caricature of the show’s actual longtime host Jim Lange (1932–2014), who calls Sheryl a “cunt” before the recording begins and seasons his galloping sexism with a hefty dose of racism. Sheryl is obliged to change into a more feminine puff-sleeved frock and given an innuendo-laced script of questions to recite. “Sally Field, Sally Field,” she mutters through gritted teeth. At the end of the film, she leaves Los Angeles altogether when she finds out that for her next audition she needs to provide a swimsuit photo.

As Sheryl’s Dating Game episode progresses, a (fictional) female member of the studio audience named Laura (Nicolette Robinson) recognises Alcala, Bachelor No. 3, as the man she saw on the Malibu beach with her best friend Alison on the day of Alison’s murder. She tells her boyfriend sitting next to her, but he responds with scepticism. Indignant and upset, she admonishes him for disbelieving her and then attempts to alert studio security instead. But the man at the desk directs her—spitefully it seems—to the janitor instead of the show’s producer. The next day Laura goes to the police but they are so uninterested in what she has to say that they scarcely look up from their desks. This sequence of events did not happen in real life, but it is invented to convey Kendrick and McDonald’s salient message: Western women are victimised by male incredulity and indifference when they report danger to men and then re-victimised by the psychopaths who are left to roam America as a result.

When The Dating Game resumes after a commercial break, Sheryl decides to ditch the canned questions she has been provided and make up her own feminist substitutes: “What are girls for?” she asks Bachelor No. 1. “You know,” he replies uncertainly, “having fun with.” To which she chirps, “Gloria Steinem would be proud!” Unfortunately, this feisty act of insubordination does not prevent her from picking the worst of the three options because Alcala tells her exactly what she wants to hear: “I guess I’d have to say that that’s up to the girl,” he reassures her when she asks him the same question. Alcala, who in real life had a tested IQ of 135, knows how to play Sheryl like a violin—and wouldn’t Woman of the Hour have been interesting had Kendrick and McDonald followed this narrative thread to its logical conclusion? Alcala does more of the same when he invites Sheryl to have a drink at a nearby dive bar after the show, chatting her up knowledgeably over Mai Tais about Edward Albee and Sam Shepard, her two favourite playwrights. It is only when he probes her to discomfort about how she feels about being “seen” that she becomes uneasy.

But fortunately, sisterhood is a powerful corrective to toxic masculinity in this movie. Sheryl has only to send a beseeching glance at the waitress, who promptly announces that closing time has passed and she cannot serve the second round of cocktails Alcala has just requested. Similarly, the middle-aged makeup artist who touches up Sheryl during the commercial break also provides some sisterly words of warning. Selection of the correct bachelor boils down to one question, she advises: “Which one of them will hurt me?” American women are alive to the danger all around them and quick to caution and rescue. Men, on the other hand, are either oblivious or indifferent. When Amy, the young runaway, tries to signal her distress from Alcala’s car to a passing male pickup driver, he simply sails off in his truck.

II.

The real-life Dating Game episode on 13 September 1978 was remarkably different from the movie version, in ways trivial and important. Rodney Alcala (then aged 34) appeared as Bachelor No. 1 (not No. 3) and he was slender and strikingly handsome, unlike the pudgy and lank-haired screen version portrayed by Zovatto. The real-life Cheryl Bradshaw, unlike the petite and attractive “Sheryl” portrayed by Kendrick, was a robust extrovert with enormous front teeth and a feathered hairdo that filled up the television screen. She wore a girly puff-sleeved midi-dress, much like the one Kendrick is forced to wear on the show, except that Cheryl’s dress was cut low to display a bosom far more capacious than Kendrick’s and swimsuit tan lines on her chest that no one in the show’s makeup department had bothered to cover up. When Cheryl sat down onstage (shielded from the bachelors’ view by a screen but still visible to the studio audience), she hiked up the skirt of her dress to mid-thigh.

The host, Jim Lange, introduced Cheryl as a former schoolteacher in Phoenix, Arizona. Drama was apparently her specialty, and it is probable that she—like her fictional counterpart—had moved to Los Angeles to try her fortune on the silver screen. “Actor” and “aspiring actor” were the proclaimed professions of many Dating Game participants of both sexes during those days, including the two other bachelors who appeared as contestants along with Rodney Alcala that night (in the movie they are a medical intern and a furniture designer).

Although Woman of the Hour’s script implies that an actor’s appearance on The Dating Game was a dip by the desperate into pop-cultural schlock, it was actually a well-recognised career-boosting strategy that allowed Hollywood’s relative unknowns to display their telegenic looks and charisma to the nation’s public. Along with Sally Field, actors like Farah Fawcett, Suzanne Somers, Tom Selleck, Steve Martin, Burt Reynolds, Karen Carpenter, and Arnold Schwarzenegger all made Dating Game appearances before they became famous. The show was a much-watched daytime television staple for most of the second half of the 20th century, on ABC and in syndication from 1965 through 1980. It was later revived in short-lived iterations during the 1980s and 1990s.

A regular feature of the real-life Dating Game during its early years was the onstage trading—between host Lange, the three bachelor-contestants, and the bachelorette, whom Lange always called “the young lady”—of bawdy double entendres. A lot of this kind of thing would shock today’s viewers, accustomed as we now are to the decorousness imposed by a half-century of feminist activism. (The Dating Game’s daytime-television twin, The Newlywed Game, likewise specialised in cringe-making innuendo; “making whoopee” was its trademark euphemism for sex. Blame it all on the paradox of the FCC’s still-rigorous prohibitions on four-letter words coupled with the new freedom to talk openly about sex on television.)

Indeed, one of the surprising contrasts between the real-life Bradshaw episode and its Kendrick/McDonald fictionalisation is how much raunchier—and even downright Elizabethan—the bad-pun repartee got in real life. The Woman of the Hour script preserves only a little of this: “She used to work massaging feet but quit when her boss asked her to work her way up.” That was one of Jim Lange’s actual lines on the show. This, from the movie’s Bachelor No. 2, is an Ian McDonald invention: “Oh, I’m a big old green salad with the vinaigrette on the side because I like things undressed.” It’s racy, but it pales in comparison to the badinage that actually took place between Cheryl Bradshaw and Rodney Alcala:

Cheryl: I am serving you for dinner. Bachelor No. 1, what are you called and what do you look like?

Alcala: I’m called the banana, and I look really good.

Cheryl: Can you get a little more descriptive?

Alcala: Peel me.

Cheryl didn’t invent her own questions on the actual show. She dutifully delivered her scripted lines on cue and with gusto, not with the disdain she exhibits in the movie, and the studio audience egged her on with hoots and cheers.

The real-life Cheryl Bradshaw, who is now deceased, was obviously no Ivy League graduate and she had probably never heard of either Edward Albee or Sam Shepard. But she did have one thing going for her that Anna Kendrick deliberately denies her fictionalised counterpart for ideological reasons: the common sense to recognise a dangerous creep within minutes of meeting him. The prizes for the winners of The Dating Game were chintzier and less elaborate than those offered to Bradshaw and Alcala in the movie. In reality, the couple was offered a trip to Magic Mountain and free tennis lessons, while in the film, the show provides a weekend in the upscale beach-resort town of Carmel. But when Alcala tried to press Bradshaw after the show to meet up the following day in advance of their official date, she immediately called the show’s producer, Ellen Metzger, and told her, “I can’t go out with this guy.” In a 2012 interview with the Sunday Telegraph, Bradshaw explained, “I started to feel ill. He was acting really creepy. I turned down his offer. I didn’t want to see him again.”

But Kendrick doesn’t allow her fictionalised version of Bradshaw to act promptly on that sixth-sense, because she did not want the audience to conclude that Alcala’s other female prey were somehow culpable for failing to spot the warning signs Sheryl identified. “I think there was a point,” Kendrick said in an October 2024 interview with Entertainment Weekly, “where one of the producers was asking if there should be some really clever way that [the fictional Bradshaw] outsmarts or outwits Rodney, and that’s why she survives. And I was like, ‘I think that that would do a disservice to the other women who were no less intelligent than her, and that sometimes it’s a combination of trusting your gut, but sometimes it’s too late for that.’” So, even though the real-life Cheryl Bradshaw did trust her gut and escape a predatory psychopath, Kendrick wasn’t prepared to show that. Doing so would have violated the feminist precept that no woman should ever be told that had she taken sensible precautions, she might have avoided becoming the victim of a sex crime.

Instead, Kendrick invents another episode for the movie that never actually took place: Sheryl Bradshaw, unlike her real-life counterpart, agrees to go drinking with a man she has met only minutes before at a seedy tavern near the studio in the middle of the night. Having done so, it slowly dawns on her Columbia-educated brain that Alcala is not the sensitive artiste he played on The Dating Game, and she has to rely on a sympathetic cocktail-waitress to get out of the precarious situation she realises she has walked into. Then, when Alcala stalks her across the parking lot as she hurries to her car, she is saved by a deus ex machina: a group of young men emerges from the studio just as Alcala is about to force open her car door and do God-knows-what to her in the way of uncontrollable violence.

III.

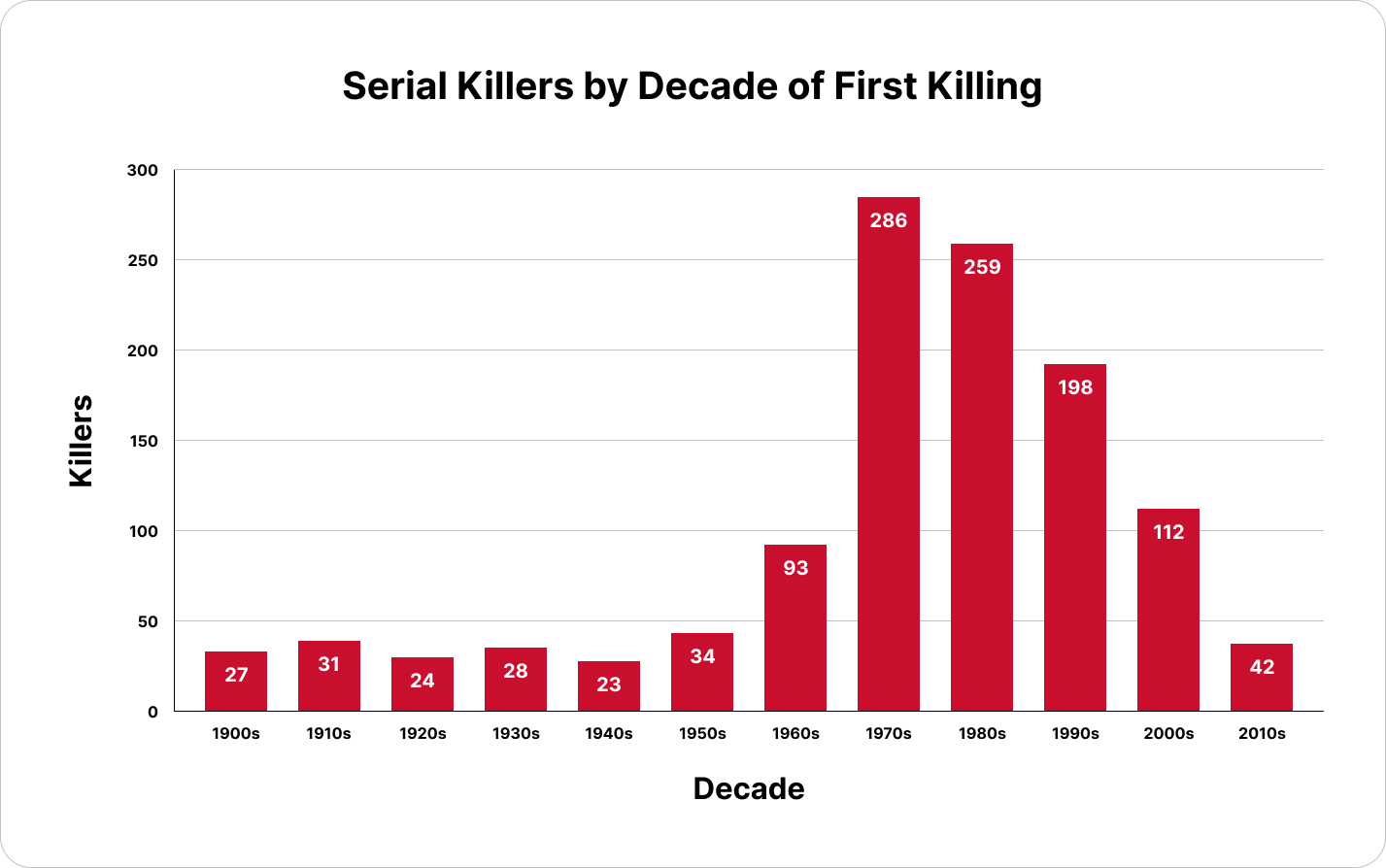

Woman of the Hour presents the 1970s as a kind of pre-#MeToo Dark Age—female consciousnesses might have been raised by the efforts of Gloria Steinem and her ilk, we are told, but men, still not sufficiently steeped in feminist awareness, continued to indulge in every sort of obnoxious and/or predatory sexism without sanction. The 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s were certainly a golden age of serial killers, the most notorious of whom preyed upon young females and augmented their slaughter with sexual violation. The most iconic of these was probably Ted Bundy, executed in Florida in 1989 for three first-degree murder convictions. He would eventually confess to the murder of nearly three dozen women and girls across America between 1971 and 1978.

Bundy’s usual modus operandi was picking up hitchhikers around college campuses or using his good looks and charm to lure victims into his car on some pretext or other. Occasionally, he broke into their homes while they slept. He bludgeoned some of his victims to death, and strangled or cut the throats of others. Like Alcala, he typically raped his victims before he killed them, or else he sexually molested their corpses after they were dead. He claimed to have decapitated around a dozen of his victims and kept their severed heads in his apartment as mementos. And Bundy, like Rodney Alcala, was a good-looking man. During his 1979 trial in Florida, dozens of women flooded him with love letters and photographs of themselves. One of these women, Carol Anne Boone, married him and bore his daughter.

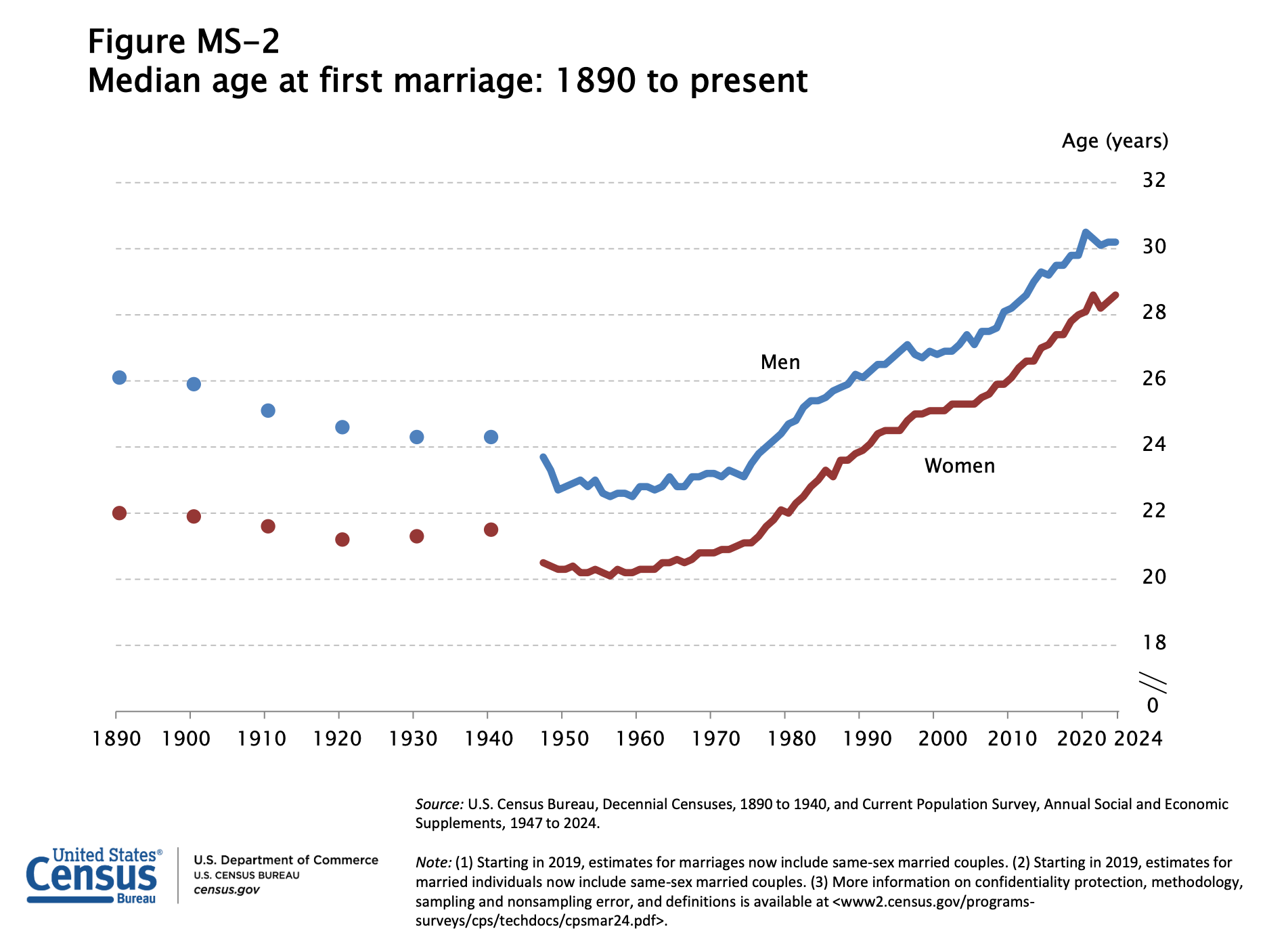

By the end of the 1960s, radical changes in women’s lifestyles and economic status, brought about by the combined effects of the feminist and sexual revolutions, had resulted in unprecedented numbers of young single women living alone. The median age of first-time marriage for women was already creeping upwards thanks to advances in birth control and a relaxation of mores that encouraged premarital sexual experimentation without fear of pregnancy and shotgun nuptials. According to the US Census Bureau, the women’s median age for first marriage had been 20.3 in 1960, but it was 22.3 by 1980. Furthermore, thanks to the availability of high-paying careers in law, medicine, journalism, and corporate management that feminism brought about, young working women who in the past might have lived at home with their parents or bunked with roommates to save on rent could now afford their own apartments, condominiums, and houses.

There was an element of naivety in all of this, too—women didn’t just want to be liberated from past constraints, they also wanted to appear to be liberated. In Woman of the Hour, Charlie the stewardess invites a complete stranger into her apartment—as her real-life counterpart, Cornelia Crilley, also appears to have done in 1971. Sarah gets into a car with a complete stranger and lets him drive her into the middle of nowhere—just like her own real-life counterpart, Christine Ruth Thornton, apparently did in 1979. Young women regularly hitchhiked alone, ran away from home as teenagers to live on the streets like Amy, and went home with men they’d picked up in bars, like New York City schoolteacher Roseann Quinn, who was stabbed to death in 1973 and became the model for Diane Keaton’s Golden Globe-nominated character in Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977).

This was all part of the free-spirit ethos of the time—young women were invited to assume that they were perfectly able to take care of themselves all by themselves in situations that seem to defy commonsensical prudence. And as might be expected, predatory and manipulative men quickly learned that shaming women for their sixth-sense hesitation could be a useful instrument of seduction: “Do I scare you?” “Don’t be uptight” or “a square” or, worse, “middle-class.” No acolyte of Gloria Steinem wanted to hear that.

What this amounted to—and amounts to even now in other forms—was a categorical denial of the biological fact that the vast majority of men are exponentially—even lethally—stronger than the vast majority of women. Men commit 95 percent of homicides, and a 1994 study found that 47.5 percent of female victims are strangled and that women “were commonly murdered by the aggressor’s bare hands within the setting of conflicts in relationships.” Feminists may choose to believe the pleasant fantasy that 5’7” Daisy Ridley can overpower 6’2” Adam Driver in The Force Awakens. Some of them may even choose to believe the less pleasant fantasy that when trans mixed-martial-arts fighter Fallon Fox fractured the skull of her biologically female opponent Tammika Brents in a 2014 match, it was because Brents wasn’t good enough at her sport.

One thing that Woman of the Hour does get right is Marilyn the makeup artist’s admonition to Sheryl about the male sex: “Which one of you will hurt me?” And the one thing that Margaret Atwood got right (painful as it is for me to admit) is her famous quip, “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.” It’s not that all men are—or were during the 1970s, as Anna Kendrick implies—on a misogynist trajectory the end point of which is rape and strangulation. It’s that men have the physical capacity to rape and strangle—just as they have the physical capacity to defend their families and haul people out of burning buildings. It is women’s responsibility to find the latter men to bond with, and to always watch out for the former.

I can speak of this firsthand. In 1978—the year Cheryl Bradshaw met Rodney Alcala on The Dating Game during the final phase of his crime spree—I was a young woman living alone in an apartment in Los Angeles. On the last night I ever spent in that apartment, in March 1978, Alcala had already carried out two of the six rapes and murders he eventually committed in California before being arrested for good. But no one had ever heard of him, or connected any of his crimes, or identified the killer as the registered sex offender who was supposed to be behaving himself on parole.

But at the same time—and Anna Kendrick fails to mention this detail in her movie—there was an exceedingly well-publicised rapist and murderer of women actively at work in the semi-mountainous area north and east of downtown Los Angeles where I lived: the Hillside Strangler. It would later emerge that there were actually two Hillside Stranglers working in tandem—Angelo Buono and his adoptive cousin Kenneth Bianchi—but no one knew that at the time. From October 1977 through February 1978, Buono and Bianchi kidnapped, tortured, sexually violated, and murdered, usually by strangulation, ten girls and young women in that area. (An eleventh kidnapping victim, Catharine Lorre Baker, showed the pair a photo of herself as a child sitting on the lap of her famous father, Peter Lorre, and they let her go, probably fearing an even more aggressive manhunt.)

Some of the Hillside Strangler victims were prostitutes picked up when Buono and Bianchi impersonated police officers, but two were schoolgirls aged twelve and fourteen. Buono was arrested in January 1979 after an intensive police investigation, but Bianchi fled to the state of Washington, where he murdered two more women and remained at large until that October. Like Alcala, both men escaped the death penalty despite multiple murder convictions. Buono died in a California penitentiary in 2002, but Bianchi is still alive, serving out his life sentence in Washington.

I followed the news stories only fitfully, but I was terrified of the Hillside Strangler. And yet, it never occurred to me to move out of my apartment in the hilly epicentre of Strangler menace. That part of East Hollywood is gay-centric and artily gentrified today, but back then it was a shabby near-slum that baked, shrivelled, and withered under the relentless Los Angeles sun. My apartment was a dump. It was part of a bungalow court, a double row of tiny 1920s cottages arranged along a corridor of overgrown agaves and tired palm trees. Architecture buffs love bungalow courts—so vintage California!—but tile roofs (in my case, mostly faux) and prairie windows go only so far when you have to spend three days on the phone trying to get the landlord over to poison-blast the cockroaches. The most dangerous feature was the flimsy window-screens, the latches of which could easily be unloosed by an intruder patient enough to jiggle them sufficiently.

And so it was, one night in March 1978, that I awakened in my bed to the lamp being switched on and the face of a strange man hovering above me. Tied around his head, pirate-style, was a blue and gold Yves Saint Laurent silk scarf that I had borrowed from my mother and left lying on my dining table. In his hand he was holding one of my own kitchen knives. I had been working late at my office, and he must have spotted me in my car and followed me home. He had broken into my apartment, the police later discovered, by unlatching the window screen in the kitchen above the sink, where I had left the window ajar (more foolishness on my part). He had obviously been in my apartment for some time—I prefer not to think about how long—as I showered and got ready for bed. I later recalled that I had heard my cat jump from something before I went to bed, but I hadn’t bothered to investigate.

He told me he was going to kill me and began to push me out of my bed and into the living room, an arm wrapped around my throat in a chokehold and the knife held out of reach in the other. My mind raced. How am I going to get out of this? The apartment’s front door was in the living room, but he was so much stronger. The arm across my throat was a steel bar, and he kept repeating, “I’m going to kill you.” In my mind’s eye, I could already see my funeral—crocodile-tear-shedding relatives tut-tutting about the ignominious end to a spinster’s pathetic life. Finally, he sat himself down on the living-room couch with my head on his thigh.

“Take off your nightgown,” he instructed. And I said, “No.” I thought I was going to die anyway, so why should I? And with that revelation came another, dimly perceived by some sub-rational, animal part of my brain now that my cerebral cortex was no longer functioning: my mouth was uncovered and both of his hands were occupied. And since I was effectively on top of him instead of the other way around, he couldn’t overpower me with his weight. So, I screamed. I screamed and screamed. Where those screams came from, I do not know, and I have never been able to reproduce them in the decades since.

Almost immediately, lights began to go on in the other bungalows. The intruder let go of my throat and lunged for the front door, sending me sprawling across the floor. Neighbours began to emerge almost at once as he bolted away. The first was the guy next door, whom I had dismissed as a stoner layabout because of the marijuana smoke and Ramones at 3am. He said he had already called the police. Some of the other men gave chase, but the intruder, who had made off with my kitchen knife and my mother’s scarf, was never found. (I helped a police artist make a sketch of him, and it turned out that he did not look anything like either Rodney Alcala or the Buono-Bianchi duo.) Five or six police officers showed up right away, all but one of whom were male. And contrary to what the contemporary viewer of Kendrick’s film is led to believe, they were all attentive, sensitive, and professional—and they were dealing with a raving barefoot banshee clad only in an ankle-length flannel nightgown.

I was insane for many weeks after that. I moved back into my parents’ house and slept in my childhood bedroom while I looked for a better apartment. Every night I would pile all the furniture I could lift in front of the door. I would dream that my parents’ throats had been slit while they lay sleeping. But then, as the massive purple bruises on my neck started to fade, so did the horror. Later, I flew to New York and stayed with a grad-school friend. At night, I would listen to his gentle snoring in the next room and feel deliciously safe. A few years after that, I met the man I married.

I have thought many things about that night over the years. One of those thoughts was the ludicrousness of the oft-repeated feminist mantra that rape is a crime of power, not lust. I beg to differ. I’ve thought, too, how blessed I am to have escaped the consequences of my own carelessness, and to have encountered an assailant who had not figured out the basic choreography of his crime. Perhaps he had assumed that he could simply frighten me into submission.

But most recently, after seeing Woman of the Hour, I’ve thought about that night and wondered at the sheer dishonesty of Kendrick’s theme of structural misogyny—or “toxic masculinity,” to use the poisonous phrase—as a malignant gene infecting every Western human male. It’s kin to what looks like her equally dishonest suppression of the Hillside Strangler in the movie. The idea that Laura would be dismissed with discourtesy and indifference by the police in September 1978 when she tried to report the man she last saw in the company of her murdered friend is absurd. The police were working night and day on the Strangler case, and every lead would have been meaningful. (In fact, the cops briefly questioned Alcala himself as a registered sex offender regarding the Strangler crimes but couldn’t connect him to anything.)

The crude caricatures that Kendrick creates of other men in the movie—turning the affable Jim Lange into a foul-mouthed, racist bully, and having the security guard prey upon Laura’s anguish with a vicious practical joke—are so implausible as to be laughable. And why pick on some poor pickup driver for keeping his eyes on the road, or on Laura’s well-meaning boyfriend with his reasonable queries about the reliability of her memory? Even the New York City movers—surly, burly males, every one—come in for implicit contempt for leaving Charlie’s furniture on the sidewalk, and therefore leaving her at the mercy of Alcala’s opportunism. Anyone who has ever had large items delivered knows that deliverymen paid by the hour don’t haul them up multiple flights of stairs unless the contract so specifies, usually for an extra fee. But this is a movie in which men invariably treat women callously and cruelly just because it’s in their male nature, in contrast to the sisterly sensitivity of females.

Equating the “toxic masculinity” of feminist propaganda that Kendrick presents with masculinity itself isn’t just a distortion of reality that is unjust to men. It is harms women as well—or at least those women who make the mistake of taking it at face value. It can undermine relations between the sexes to the point of mutual distrust and resentment. It can also terrify young women by making them reluctant to report disturbing situations for fear of being mocked and disbelieved. Worst, it discourages women from taking practical precautions against the very real dangers that genuinely bad men present—and there are always enough of them out there.

Simply acknowledging biological differences between the sexes—including the fact that men are vastly stronger and more aggressive than women—ought to be a start in helping women distinguish between the men who seek to use their physical superiority to harm them and those who will use that same superiority to protect them. Fortunately, the #MeToo era, with its destructive ideology of demonisation of the entire male sex, seems to be behind us with the vaunted 2024 vibe shift. We can only hope that it stays that way.