Podcast

Podcast #277: Anti-Zionism, Past and Present

An interview with scholar Izabella Tabarovsky about the Soviet roots of contemporary anti-Zionism and antisemitism.

Introduction: My guest this week is Izabella Tabarovsky. Izabella is a scholar of Soviet anti-Zionism and contemporary antisemitism. She is a senior fellow at the Z3 Institute for Jewish Priorities and a contributing writer at Tablet. She is the author of two articles for Quillette: “What my Soviet Life Taught me about Censorship” and “The language of Soviet Propaganda: Progressive anti-Zionism and the Poisonous Legacy of Cold War Hatred.” In February, Izabella was scheduled to give talks at two Finnish universities: Abo Akademi University in Turku, at which she was to give the keynote address at an international conference on antisemitism; she was also scheduled to give a public talk at the University of Helsinki. The title of both lectures was to be “From the Cold War to University Campuses Today: The USSR, the Third World and Contemporary Anti-Zionist Discourse.” However, following a campaign on social media, both those talks were cancelled. Today I’ll be talking to Izabella about those cancellations and more widely about the connections between Soviet anti-Zionism and contemporary anti-Zionism, and also little bit about the history of Finnish involvement in antisemitism. I hope you enjoy my talk with Izabella Tabarovsky.

Iona Italia: So Izabella, perhaps you could start by just talking about the specific situation, the specific circumstances of the cancellation of your two recently scheduled talks in Finland. How you came to be invited to give those talks in the first place, what happened to make those, make both institutions—so one was the, I’m going to pronounce this wrong, the Abo Akademi University, I have absolutely no idea if that’s how it’s pronounced and I apologise to any Finnish speakers who are listening—and also the University of Helsinki, you were going to give the same talk at both places. I’d first like to talk about how and why you were invited to give those talks, also what happened to cause the talks to be cancelled, and how that story has continued. And then maybe we can get onto the substance of the talk that you would have given had that talk gone forward.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Sure. Perfect. That sounds good. So I’ve been for many years researching the question of Soviet anti-Israel propaganda, Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda. I wrote a piece for Quillette about it, but I started actually, I think, in 2017. So it’s been a number of years. Before that, I was researching and writing on the history of Soviet Jews and the Holocaust that happened in the Soviet territories during World War II.

I’m originally from Russia, my master’s degree is in Russian studies. So I’m a Russia person. All my life I’ve been a Russia person. I’ve always had jobs that had to do with Russia in one way or another. But for the last several years, since 2017 or so, I’ve really focused on the anti-Israel propaganda that the USSR developed and launched in the wake of the Six Day War in 1967.

We can talk about why I was researching that. But I’m saying this just to affirm that I had a name in the field and it may sound immodest, but I think I have made a contribution to the field with my research and writings. I have some academic publications, but I primarily have focused on writing for publications that write for general readers because I thought that it was really important to help people understand, to help broader audiences understand it and not let this material be locked in academic publications because this propaganda still resonates on the far left. We still hear echoes of this propaganda today in the current anti-Zionist discourse. So that’s my background on this.

I think “Abo Akademi” is how I pronounce it. I also don’t know if it’s correct. I believe it’s Swedish. It’s actually a university that teaches in Swedish. There’s a Swedish minority in Finland, which I learned. I didn’t realise that, but there is a group there that focuses on the study of antisemitism and they invited me a very long time ago. I think the lead time was like a year, maybe nine months, in advance when we first started talking and they really knew what they wanted. They knew why they wanted me. My expertise is actually pretty rare.

Now, most people in antisemitism studies focus on right-wing antisemitism, which is Nazi antisemitism and its derivatives. Very few people have really examined thoroughly the kind of antisemitism that I look at. And so they knew exactly why they wanted me. They knew where they wanted me. They knew the subject that they wanted. It was all very well thought out. The people who invited me are scholars themselves with substantial research output. So there were no accidents in this. It was all set.

Then a week before I was supposed to fly … The conference was going to start on a Wednesday, I think the last week of January, so a week before that on a Wednesday, I got an email from organisers that there was a campaign against me on Finnish social media. And, I think they phrased it very kind of politely and gently. They said, “You know, people are writing and they’re asking questions.”

And I said, “Well, what kind of questions are they asking? Let me know, is there something I can answer?” And then they said, “Well, actually, it’s more than just questions. It’s a real smear campaign.” I’m paraphrasing, but basically I understood what it was about. And why did I understand? Because we see so much of it in the US, of course, we’ve seen it in various areas and fields for many years, certainly since 2020.

Certainly those who deal with Israel and antisemitism and -Zionism and the Israel–Gaza conflict, we see this happening all the time. And by Friday, the universities caved. I had the feeling that it might happen. But I didn’t know, because I didn’t know much of anything about the academic culture in Finland. So I just waited to see what would happen, but Friday I got the email, a very embarrassed email from the organisers who I can say now are my good friends and actually fought against the decisions of their universities. But they said, “Look, the rector of our university or the dean of our university in that faculty where we are located cancelled and also the University of Helsinki cancelled.”

And that was it, but I had seen some of that. I asked them to send me screenshots of what was being posted. It was mostly on Instagram. There were a couple of accounts. They were all anonymous. One was called, I think, Researchers for Palestine. Another was called, I think, Students for Palestine, which is not the same as Students for Justice for Palestine, we think. We don’t know. Nobody really knows. You see, that’s the problem with these campaigns, that they’re anonymous.

I saw that they accused me—what happened is they looked on my social media feeds, they looked at my X feed. They saw that I am pro-Israel. They saw that I questioned some of the dogmas that have been circulating. Some of them are just entirely incorrect in my view. And some are simply dogmatic attempts to shut down debate. So they called me a genocide denier. They said that I was an apartheid-supporting settler-colonial legitimising an apartheid settler-colonial entity and a couple of things like this. Again, things that we have all heard.

And then there was also another fun touch is that there was a mistake. Somebody on the organiser’s team added the magic three letters to my name, PhD, which I don’t have and I never claimed to have. They made a mistake. It happens to me at academic functions. People just assume that if you’re speaking, it means that you’re a PhD.

So they claim that I misrepresented my academic credentials. The organisers say that as soon as they noticed, they removed the letters, but the campaigners noticed and attacked me on that. So that was briefly what happened. And then a whole other stage started and we can talk about it.

II: It seems really extraordinary and almost unbelievable that you would be disinvited from a conference on antisemitism because you were pro-Israel. I mean, surely they would expect most speakers at a conference on antisemitism to be pro-Israel.

IT: You know, maybe, yes, maybe not. It’s complicated in the Jewish community. There are Jews, students, professors who are vehemently anti-Israel. So I don’t think that they necessarily expected that. But for me, the reason this was so ironic is that I’m Jewish myself. I grew up in the USSR and the things that I write about, I come from it as a researcher, but I also tell my personal story and I talk about how Soviet Jews were discriminated against at a time when the USSR was conducting its anti-Zionist campaign. So all of this language that we’re hearing today that Israel is a genocidal terrorist entity, settler-colonial, apartheid, fascist, Nazi, et cetera, et cetera, we’ve heard all of this and we know, and this was part of the reason I was writing so insistently for many years and really trying to address myself to the broader audiences rather than academic audiences is that we know what happens to Jews once this rhetoric takes over institutions and entire societies. You can claim all you want that anti-Zionism is not antisemitism, but the outcomes once that rhetoric takes over, once that way of thinking takes over, once that explanatory logic is there that positions Israel as kind of the heart of all evil in the universe, then antisemitic outcomes follow. And by the way, the campaigners, for them, the ultimate sin that they accused me of was that I equated anti-Zionism with antisemitism. So all of these things, they’re a matter of debate, they’re a matter of discussion, but they want everybody to think the same way and say the same things. And that too is extremely familiar to me as a former Soviet citizen.

II: Can you tell our listeners something about the talk that you were going to give? It was called—and you were going to give this talk at both places—“From the Cold War to University Campuses Today: the USSR, the Third World and Contemporary Anti-Zionist Discourse.” Could you run us through what the main headers for that talk were going to be, what your main argument was going to be?

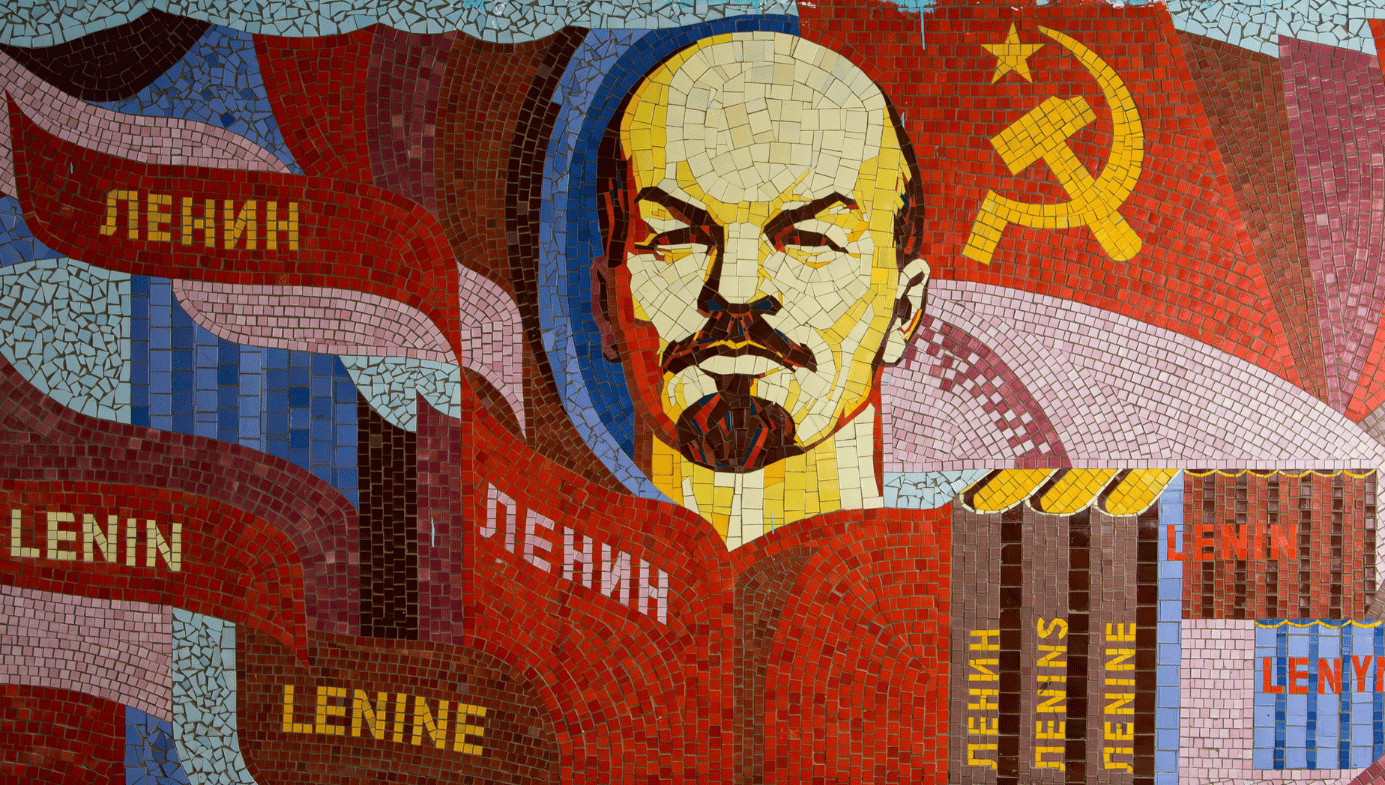

IT: Sure. I give a version of this talk quite often. I give an overview of how the Soviet Union viewed Jews and Zionist Jews. And I start essentially with Lenin and Stalin, but then I focused primarily on what happened after 1967, because I think that that is when it became, that is when Soviet anti-Zionism evolved into a whole new stage. It first of all went international or maybe first of all, it became really comprehensive.

They developed this as a body of rhetoric and thought, and they went international with it because they saw Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War as a comprehensive challenge for the Soviet Union in the Middle East—also in the US because there were so many Jews. When the Soviets looked at the United States, they saw that there were so many Jews and they were influential. There were so many Jews in influential places, which was very unusual for the Soviet Union. And they immediately saw it as suspicious. And these Jews were pro-Israel. And they saw it also as an internal challenge because the Six-Day War stirred Jewish nationalism inside the country. And Soviet Jews started to connect to their Jewish identity far more than they had been permitted before. They started wanting to emigrate to Israel. So a whole campaign also inside the country started for emigration. And the Soviets, because Soviet political culture, as often happens in authoritarian and totalitarian states was prone to conspiracy theories and paranoia. And this is only fifteen years after Stalin died or less than fifteen years.