Politics

The Political Foundations of the DOGE Scam

The Trump/Musk administration’s approach to cutting costs makes good political sense in the short-run. But from a longer-run governing perspective, it is a recipe for disaster.

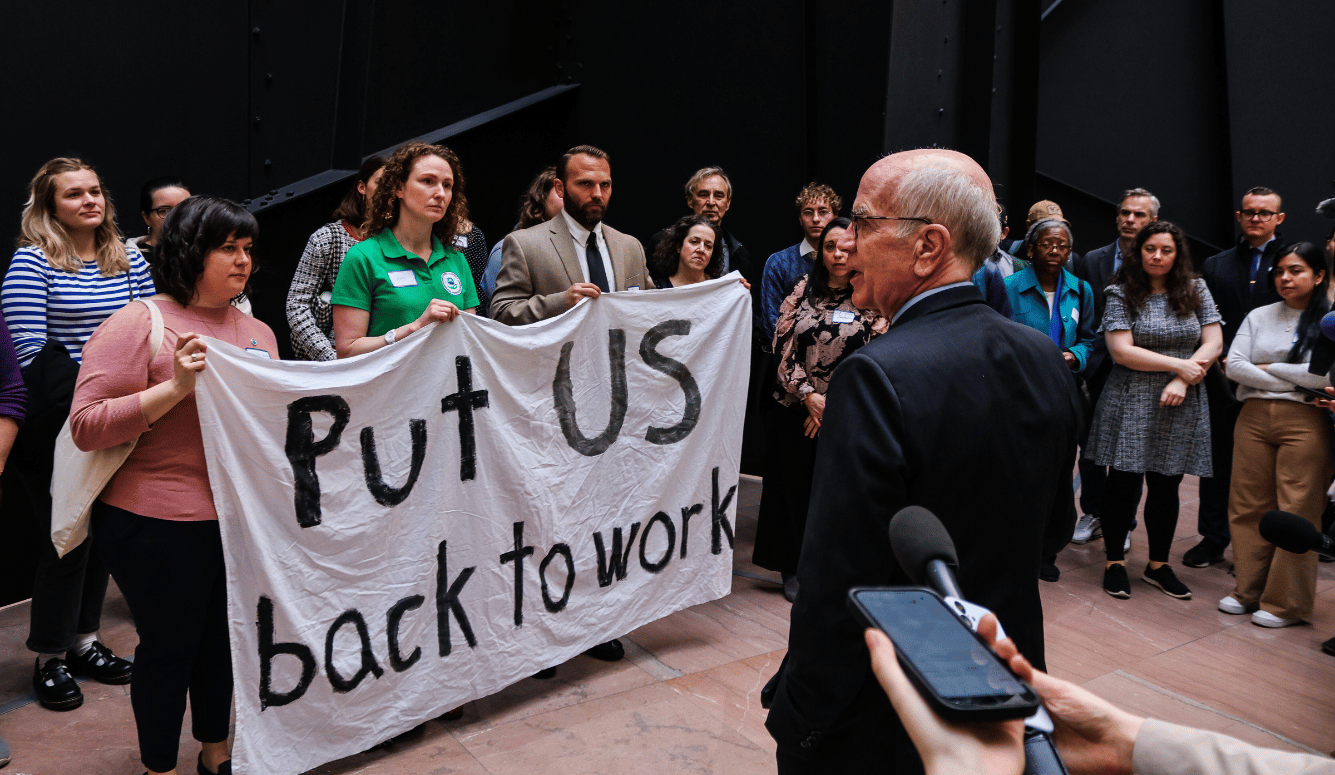

At an unusually contentious cabinet meeting on 6 March, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy got into an extended and heated argument with Elon Musk. Each side accused the other of lying. What was the burning issue at the heart of this confrontation? Ukraine? Immigration? Tariffs? No, the number of federal civil servants who should be fired immediately. Over the past several weeks, slashing the federal workforce has been the central goal of Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE). This has generated scores of lawsuits, many of which the Trump/Musk administration has lost. Now there is angry pushback from the Trump appointees responsible for running federal agencies.

Amid the chaos created by the frenetic initiatives of the Trump/Musk administration, a central puzzle is what the DOGE boys are trying to achieve with this assault on the federal bureaucracy. Are they simply smart-ass tech-bros trying to break things as fast as possible? Libertarians dedicated to substantially shrinking government? Or budget busters who really believe that they can quickly find US$2 trillion in waste, fraud, and inefficiencies in the federal government?

We do not know how soon this project will crash on the rocks of political and policy reality, or how much harm it will impose in the meantime. But an old chestnut of political-science wisdom can help us understand the logic of this unprecedented attack on federal administrators and the limits of its success.

In 1968, public-opinion scholars Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril published The Political Beliefs of Americans, in which they provide extensive evidence that Americans are “ideologically conservative” but “operationally liberal.” By the former, they meant that American voters are distrustful of centralised and bureaucratic government. They don’t like regulation or taxation (who does?). In the abstract, therefore, they prefer smaller government with fewer responsibilities to larger government with more benefits.

At the same time, Free and Cantril noted, Americans like the benefits, services, and protections provided by federal, state, and local governments. Only a tiny percentage of the public wants to cut spending on Social Security, healthcare, education, environmental protection, veterans’ programs, infrastructure, or assistance to needy children. Indeed, a majority usually want to spend even more on these programs. Over the past several decades, poll after poll has confirmed this. So has congressional politics. When Republicans have proposed major cuts in these programs, they have faced retribution at the next election.

One of the few programs to lack such support is foreign aid—largely because the public vastly exaggerates the size of the foreign-aid budget. Unsurprisingly, this was the first target of DOGE. It is likely that when the full consequences of these cuts become apparent, funding will quietly be restored.