AAUP

An Unsettling Approach to Academic Freedom

The American Association of University Professors once defended heterodox thinkers. It now supports mandatory DEI statements and calls rival organisations right-wing stooges.

Defenders of free inquiry owe a debt to an academic crank from the turn of the twentieth century. Edward Alsworth Ross taught economics and sociology at Stanford University in the 1890s. A gifted public speaker, he found a large audience beyond academia, and often gave addresses on left-wing themes such as workers’ rights, the plight of farmers, and the exploitative nature of railroad companies. But alongside these progressive views, Ross also espoused a stark nativism. The two sides of his thinking came together 125 years ago, in a speech to a labour association in San Francisco, in which Ross advocated helping white workers by turning away Asians. “Should the worst come to the worst,” he told his working-class audience, “it would be better for us to train our guns on every vessel bringing Japanese to our shores rather than to permit them to land.’’

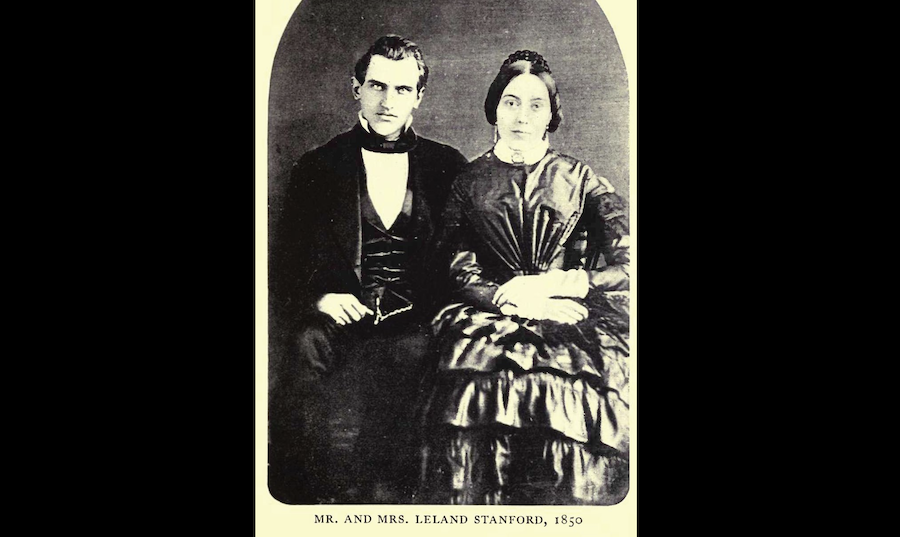

Ross’s xenophobia is hard to stomach today. But that wasn’t the main thing that got him in trouble. It was that his San Francisco speech, along with another in which he urged the government to buy up urban railroads, upset Jane Stanford. A co-founder of her namesake school along with her late husband Leland, she wielded so much control after the latter’s death that she was called Mother of the University.

To be fair, Jane did express objections to Ross’s remarks on anti-racist grounds: in her letter to Stanford’s president demanding the professor’s ouster, she cited his rhetoric “drawing distinctions between man and man, all labourers and equal in the sight of God, and literally play[ing] into the hands of the lowest and vilest elements of socialism.” But whatever empathy she had for immigrants was outweighed by a less noble concern.

Stanford’s founding had been made possible by the enormous fortune that Leland had accumulated in the railroad business. And so Ross’s outspoken criticism of railroads and their corrupting effects on politics (“a railroad deal is a railroad steal,” he once purportedly told a class) caused Jane to seek his ouster even before he’d delivered his anti-Japanese speech in 1900. In fact, her previous attempts to end Ross’s employment had resulted in his transfer from the department of economics to sociology, a compromise arranged by Stanford’s president.

Ross’s San Francisco speech put an end to Jane’s willingness to compromise, likely due to the historical themes he’d evoked. One of the few groups that had taken on the railroads and won was the Workingmen’s Association of California, a nativist political party (slogan: The Chinese Must Go!). Party demagogues had helped whip up support for the Chinese Exclusion Act, an 1882 law that banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States, thereby shutting off a source of cheap labour for Leland’s railroad. (This was why Jane associated Ross’s racism with socialism in her letter.) She now applied such strong pressure on Stanford’s president that he had no choice but to ask for Ross’s resignation.