Politics

From Imperium to Expansionism

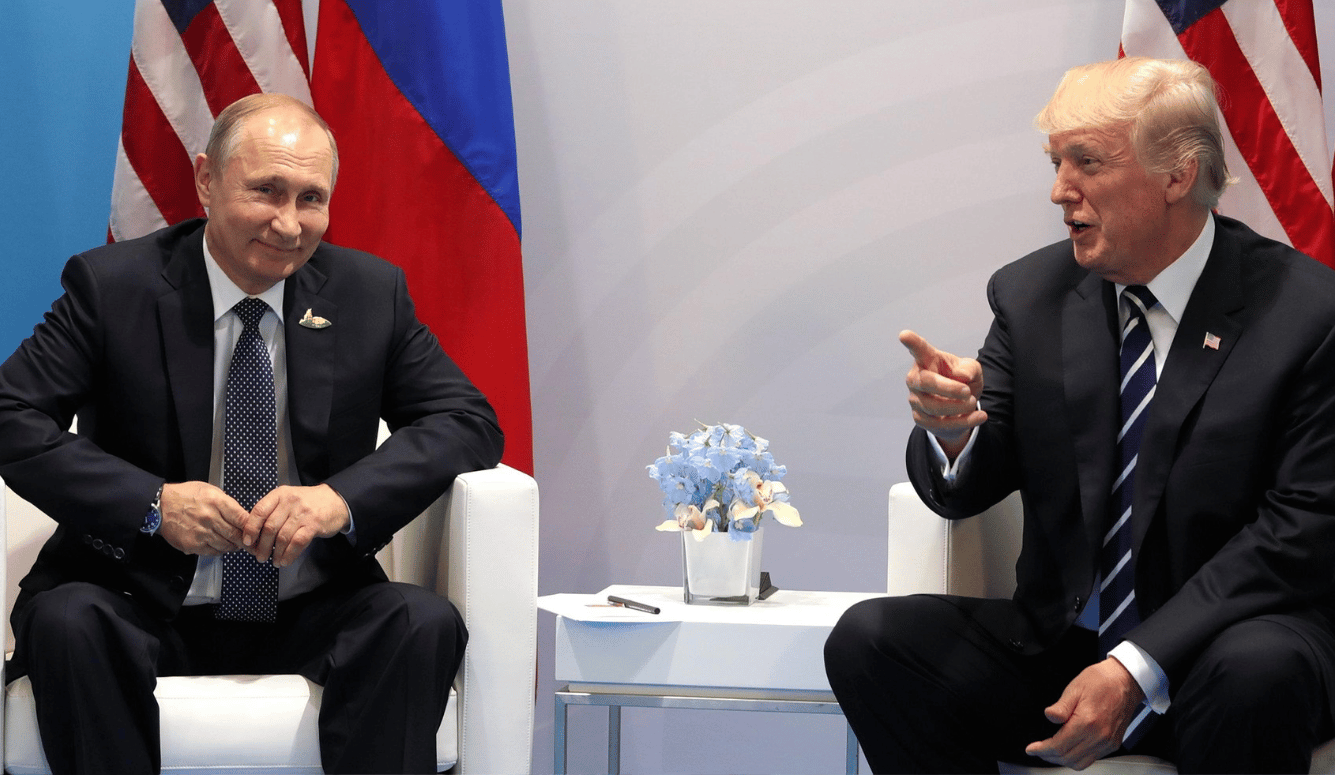

Donald Trump is often described as an imperialist and an expansionist and these terms are usually used interchangeably. Neither of these descriptions is meant to be flattering, but the larger problem is that they are imprecise.

After the Second World War, many Americans held a romantic view of their country’s role in the world. They believed that through American intervention, the world would become safer and wealthier. Americans across the demographic spectrum shared this high hope, including government officials looking to bring peace and prosperity, businesspeople looking to make a profit, military personnel looking to plant the flag, and young idealists looking to do good. That imperial vision was encapsulated by the phrase “Pax Americana,” or American Peace.

The American Empire largely delivered on its promise to a war-shattered world that life would improve through American engagement. To this day, America remains the pivot around which much of the world revolves, whether as home to the world’s reserve currency, guarantor of the open seas, or food supplier during times of famine. Yet in recent years, many Americans have come to resent their imperial role. Many of them voted for President Trump because they approved of his promise to dismantle it. Trump has never formally declared that his goal is “the end of empire.” It is unlikely that he thinks in such terms; nor do most of the people who voted for him. Nevertheless, this will be the consequence of Trump’s policies and rhetoric.

The current controversy surrounding the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) illustrates many of the complaints and suspicions Americans harbour about their country’s imperial role. First, they say that American aid costs too much and the country simply can’t afford it. Second, they wonder why Americans are sending aid to their economic competitors at all. Indeed, some countries that receive US aid and/or security assistance then impose tariffs on American goods. Third, American commitments abroad risk drawing the country into “forever wars” that critics believe are none of our business. In particular, people worry that the 37 percent of USAID assistance sent to Ukraine last year portends deeper involvement in that country’s war with Russia. Fourth, USAID fails to promote traditional American values, they complain. Instead of supporting freedom, for example, it sponsors abortion clinics, diversity seminars, and transgender art.

Arguments like these were also heard during the 1970s, when the American Empire teetered after government spending on welfare and warfare triggered inflation. But the empire’s detractors never reached critical mass. Prosperity during the 1980s calmed people down and the Soviet Union remained a threat that demanded American engagement around the world.

So, what is an empire? And how can the Trump agenda mean the end of the American imperium when Trump himself is routinely called an “imperialist”? He is called this in what many people believe to be the only sense of the word: immoral, bullying, and grasping. Trump is also called an “expansionist,” which today carries the same negative connotation as “imperialist.” But the terms are not synonymous. A recent post by public intellectual Francis Fukuyama exemplifies this confusion when he condemns Trump for what he calls an “expansionist mindset” that has found expression in a “new American imperialism.” Although Trump sometimes behaves as an “old-fashioned imperialist,” according to Fukuyama, he has lately become something of “neo-imperialist.” None of these descriptions is meant to be flattering. But the larger problem is that they are imprecise.

To understand whether Trump is an imperialist, an expansionist, or both (or neither), and to understand Trump’s likely impact on American foreign policy, we need to return to fundamentals. We need to understand what empire means.

In 1980, on my final college exam in political science, I was asked whether or not economic interests could explain postwar American foreign policy. Three well-known exceptions to the rule allowed me to reply in the negative. First, America refused to recognise Mao’s China after the communist takeover in 1949, despite clear economic incentives to do so. Indeed, Great Britain recognised the new government almost immediately, calculating that British traders would benefit from a stable, industrialising China. In the US, however, anti-communist ideology trumped economics. Second, in the 1960s, much of American business was ambivalent about getting seriously involved in Vietnam. Translated into real terms, fervent anti-communism demanded big government and big armies paid for with tax increases. But again, ideology triumphed, and the Vietnam War was the end result. Third, in 1948, the US recognised the new state of Israel, which made little sense economically. By sheer population, the Arab market had much greater potential, not to mention large oil reserves. Unsurprisingly, many of the major banks and corporations that defined the Eastern Establishment of that era strongly opposed recognition. Nevertheless, ideology carried the day.

What was this ideology that trumped economics in the US and permitted these strange and unexpected violations of what seems like a basic law of nature? It grew out of the American people’s hopes for a more secure world—social security in the domestic sphere, national security in the foreign sphere—and went by the moniker “Cold War liberalism.” Anchored more firmly in the Democratic Party than in the GOP, it was not just a policy, but also a vision and a doctrine that envisioned organising the world on a new footing.

In the military sphere, it translated into a host of new American-led defence pacts, including SEATO, ANZUS, NATO, and NORAD. Consequently, America’s legions were stationed in parts of the world as far-flung as the British Empire. In the economic sphere, it transformed America into the world’s central player in an ever-expanding global economy. The dollar became the key medium of exchange, reserve, and liquidity, while the new ideology justified the creation of international economic institutions designed to ensure global economic stability, such as the International Monetary Fund for so-called First World countries and the World Bank for Third and Fourth World countries.

In the political and cultural spheres, the new ideology led to the creation of “soft power” institutions, such as the Voice of America and the Peace Corps, which worked to convert the world to the American way of life. So fervently did those who worked for these organisations believe in their cause that they often developed the temperaments of 19th-century missionary zealots. The ideology of Cold War liberalism triumphed over entrenched interests and steered American foreign policy in a novel direction. Along with military and economic power, it formed one of the three pillars of power that established the basis for the American Empire.

Here we can start to draw a distinction between “imperialism” and “expansionism.” In expansionism, which is the more common phenomenon, a country works to improve its economic or military position at the expense of its competitors. Expansionism proceeds from the ground up, as a country tacks on new markets or military bases to improve its position. In an extreme version of expansionism, such as colonisation, the country exploits another country’s people and natural resources through direct takeover and occupation.

Many of the great 19th-century American presidents were expansionist. Thomas Jefferson expanded America’s boundaries through the Louisiana Purchase. Andrew Jackson grabbed Native American land. James Polk snagged the Southwest. Under Andrew Johnson, America acquired Alaska. In 1898, William McKinley took Puerto Rico, and in 1917, Woodrow Wilson acquired the Virgin Islands.

An imperialist country is less interested in exploiting other countries for its own material benefit than it is in sustaining a regional or global system.

Imperialism is different. In some ways, it is expansionism’s opposite. Imperialism is how America operated during Cold War liberalism’s heyday, from the 1950s to the 1970s. Echoes of that system reverberated well into the Biden administration. An imperialist country is less interested in exploiting other countries for its own material benefit than it is in sustaining a regional or global system. While the imperialist country often benefits from its empire, profit is not its primary goal. On the contrary, it may suffer under its own imperial system as it tries to preserve that system. In the case of the American Empire, the American free-trade policy permitted other countries within the imperial system to tariff American products. America also permitted alliance countries to spend less on defence and more on welfare, forcing America to shoulder more of the defence burden despite the fact that these other countries sat on the front lines. An imperial country’s primary goal is not wealth or military advantage; its goals are order, stability, and control, sometimes even at its own expense.

Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson were classic Cold War liberals and imperialists. Kennedy’s “we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship” inaugural speech is sloganistic shorthand for the sacrificial spirit of the American Empire at its peak. For non-ideological, business-minded Americans eager to invest in communist China, to avoid the Vietnam “forever war,” or to plunge into the huge Arab market without the baggage of Israel weighing them down, the empire made little sense.

Imperialism operates differently from expansionism. Rather than build wealth or power from the ground up through the acquisition of new markets and domains, imperialism organises an entire region, sometimes even the entire world, from the top down, again with the goal of providing order and security to all those living within the imperium. In the American Empire, the United Nations, the World Trade Organisation, and the World Health Organisation exemplify postwar institutions designed to organise the world into a new, world-spanning system.

When President Trump and his supporters criticise USAID and other American agencies for failing to put America first, they do so from an expansionist perspective. Their complaints are nothing new in the arena of international relations. After all, most countries have traditionally put themselves first. When Trump complains that Europe is not paying its “fair share,” he is being expansionist. When he seeks to negotiate bilateral trade treaties and circumvent the multilateral world economic system, he is being expansionist. When he threatens allies with tariffs to further American interests, he is expansionist. When he says he wants to take over Greenland and the Panama Canal, he is being expansionist. The whole premise of his “America First” campaign is expansionist by definition. Trump seeks to add to America’s material position by accretion from the ground up. Gone is imperialism’s top-down, world-spanning system with its dreams of world unity, its desire to bind all nations, and its promise to end war and struggle through ideologically inspired institutional creations.

Even Trump’s interest in “de-nuclearising” the world fits more appropriately under the expansionist label. America built its empire on nuclear weapons. The expansionist Air Force General Curtis Lemay once called the atom bomb “just another weapon.” But for Cold War liberal imperialists, America’s nuclear arsenal was more than just instruments of war. The imperialists understood these weapons as critical components of game theory and diplomacy, to be used by the two great nuclear powers of the era—the US and the Soviet Union—for the purpose of keeping the peace. Theories such as “mutually assured destruction” were meant to keep the world frozen—paralysed—in order and stability.

Nuclear weapons enabled a stable duopoly of power; they were not just weapons, they were pieces on a chess board. This “conservatism” infuriated China’s communist revolutionaries, who saw their chance of world revolution slipping away as the US-Soviet nuclear connection became predictable with its array of perfunctory gestures. When associated with such words as “parity,” “sufficiency,” and “superiority,” nuclear-weapon stockpiles became a way for the two countries to talk and gauge the temperature of their opponents whenever a crisis loomed, thereby keeping things under control and forestalling recklessness. To be satisfied with nuclear “parity” meant all was well. Raising demands for nuclear “sufficiency” or even “superiority” meant one party was unhappy with how political events were going, and that the other party had better adjust.

Trump’s de-nuclearisation effort may on the surface sound like progress in the sense that it would reduce the number of weapons that could destroy life on earth. But it also assumes that nuclear weapons are nothing more than weapons. Trump does not understand their strategic value, as a means of preserving a stable dialectical relationship with another country. Instead, like General LeMay, he just sees them as bombs. Therefore, there is no reason to have a lot of them since they can’t be used in any case.

Trump’s notion of a missile shield also portends the end of American empire. Expansionist in origin, it views nuclear weapons as just another weapon to be defended against. Non-ideological, non-visionary, straightforward, and commonsensical, Trump sees only the operational consequences of the weapons. He cannot imagine nuclear weapons as something useful independent of their operational consequences—a tool for unifying the world and maintaining global order.

Does America’s conversion from imperialism back to expansionism herald danger? History suggests it might. War and darkness usually descend upon the world when empires decline. The decline of the Roman Empire led to the Dark Ages. The decline of the Holy Roman Empire led to the Napoleonic Wars. The decline of the British Empire led to the two World Wars. We tend to think of empires as violent enterprises plagued by constant warfare, but the opposite seems to be true once the empire has been established. They bring stability.

In one obscure example, people often assume bloodletting was endemic in the African Zulu empire that was established by the violent chieftain Shaka during the 19th century. But this is incorrect. According to E.A. Ritter’s Shaka Zulu, the Zulu imperium was a vast area “within which, whatever was happening outside, law was respected, and peace and prosperity reigned.” Empires, by and large, have been seen as of great benefit, and their passing is regretted. Chaos might reign if the American Empire disappears.

And yet, while American imperialism may be waning, American power and influence are not, which is something of an historical anomaly. In all previous cases, when an empire declined, the imperial country declined with it, and sometimes even disappeared. That country did not convert from imperialism to expansionism, as the US is doing now. The Roman Empire, the Mongol Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Empire of Japan are just a few examples of empires that fell as the imperial nation itself fell, sometimes to the point of non-existence.

In a few rare cases, nations proclaimed themselves empires while they were weakening, such as the Joseon Dynasty, which transformed itself into the Korean Empire in 1897, thirteen years before Japan annexed the helpless country outright. But America is unique, for as the American Empire wanes, America itself is far from waning. China may hope to challenge its economy and military, but America’s are still pre-eminent. America’s conversion from imperialism to expansionism may not lead to the massive disorder that followed imperial collapse in the past.

America still has a monopoly on military power within its domains. It still plays a key role in sustaining and expanding the world-market system, despite the best efforts of BRIC countries to come up with an alternative. The American Empire’s cultural pillar—the ideological pillar that gives an empire its justification and animating spirit—has most weakened. During the 1980s and 90s, Cold War liberalism morphed into neoliberalism, which became the new cultural pillar undergirding the empire. That, too, eventually lost its appeal among average people, both in the US and around the world. Progressive—or “woke”—ideology, including identity politics, gender neutrality, borderless nations, and climate eschatology, followed, but that found little appeal except among elites, and so failed to serve as a replacement. Without an ideology or grand vision with which to electrify people and inspire them with a set of ideas about why large expanses of territory should be dominated and organised by one country, and without an activist government inspired to lead the way in building a vast economic, political, and military network, an empire simply cannot exist.

Instead, we get expansionism—the expansion of a country’s interests: in America’s case, reciprocal tariffs, negotiations for access to Ukraine’s and Greenland’s minerals, and a re-development project to turn Gaza into another Atlantic City. We also get more nationalism, which is consistent with the working-class revolutionary upheaval that brought Trump to power in the first place. Contrary to popular belief, working-class revolts show a marked tendency toward economic and political nationalism.

This is why there never was any great international economy that linked the socialist countries together during the Soviet Union’s heyday. Amid all the great workers’ revolutions in history, rarely do large transnational unities arise as a result. When workers rise up and take control of the state, they will furiously play defence against some outside oppressor, but rarely are they international in orientation. Trump’s MAGA movement belongs to this tradition. As a workers’ movement, it is nationalist and expansionist, not internationalist and imperial.

Should the passing of the American Empire be mourned for sentimental reasons? I believe so, yes. I was born at the empire’s peak; my first political affiliation was as a Cold War liberal; in the 1970s, I supported the democratic imperialism of Hubert Humphrey and Senator Henry Jackson. I felt America played a progressive role in the world. Although too young to join the Peace Corps, I imagined myself doing so to help the oppressed, to conduct democratic experiments in feudal backwaters, to spread light and progress. I imagined myself watching new societies in action after being rebuilt along American lines. I imagined myself bringing American public-health methods to Africa, or travelling with US labour leaders to plant trees in the Judean hills. That is all gone now, of course. We have gone from believing cadres to technical operatives to controversy-plagued USAID.

I once met a professor who argued that a democracy could not be imperialist, and that America was therefore never an empire. At the very least, American culture had nothing to offer the world, he argued. True, a lot of American mass culture was always a bit desolate. In the American Empire’s heyday, there were comic books, processed cheese, tuna casserole, stupid movies, velvet paintings, pet clothing, and roller derby. In politics, there were congresspeople who feared Guam might capsize if a large US naval ship docked there, or who confused missile silos with grain silos. Because America was so democratic, it was always a little crazy.

But every great empire has its own unique temperament. The Roman Empire was great but cruel. The Holy Roman Empire was great but despotic. The British Empire was great but severe. The American Empire was great but… ridiculous. But it was still great.