Art and Culture

Peanuts in Perspective

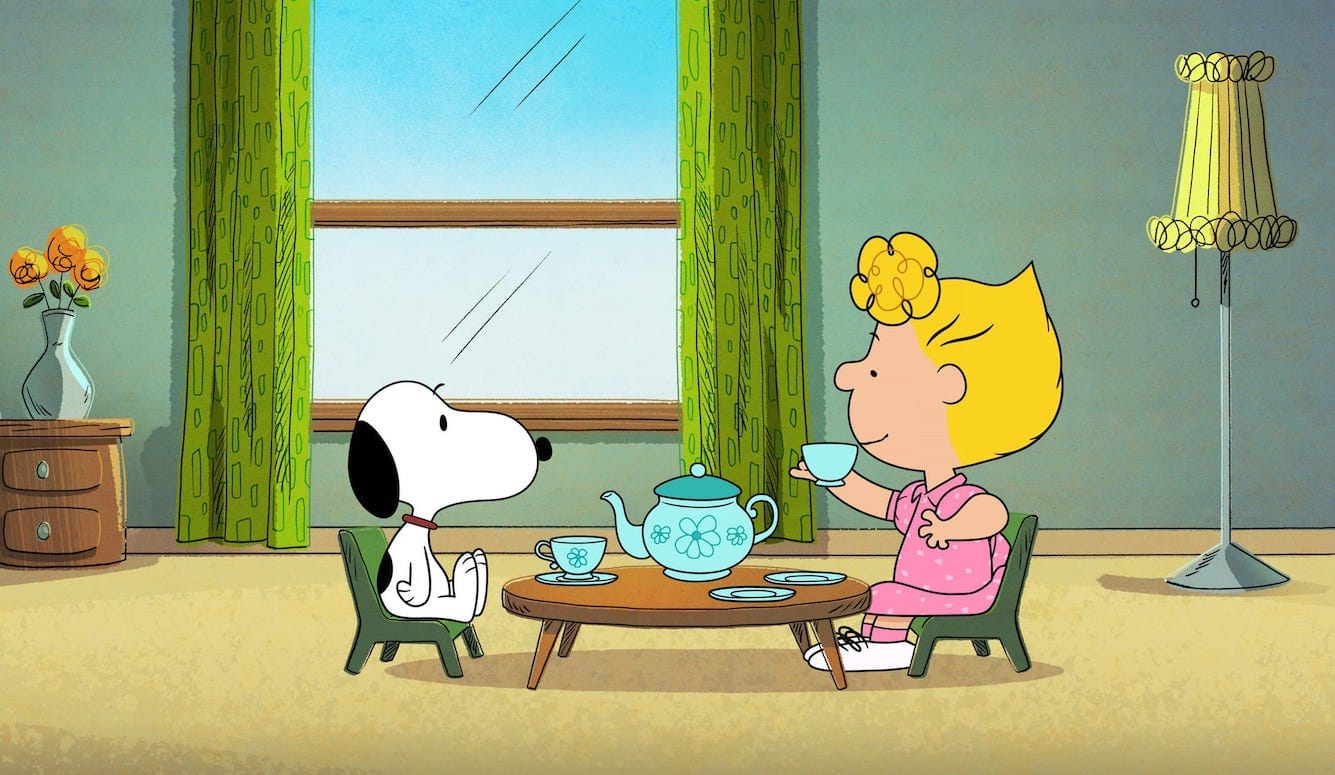

Peanuts offered parables of existential angst and longing, described through small stories about the small affairs of small people.

The thirteenth of February 2025 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the last printed Peanuts comic strip, a closure which eerily coincided with the death at age seventy-seven of its author, Charles M. Schulz, on the same day. In hindsight, Peanuts was not just another highly successful cultural product but one of the last single-authored cultural products to be internationally successful on a grand scale.

Schulz’s drawn characters—along with their catchphrases like “Good grief!” and “You blockhead!”—have become as immortal as Waiting for Godot’s Vladimir and Estragon, Catch-22’s Yossarian, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp. But his real achievement lies not in any single comic strip or character, but in the sheer extent of his fifty-year body of original work. Between October 1950 and December 1999, Schulz drew almost 18,000 unique Peanuts episodes, in addition to innumerable Peanuts posters, calendars, greeting cards, and advertisements. Peanuts is a modern saga, or, as illustrator Ivan Brunetti put it, “an epic poem made up entirely of haikus.” A handful of other twentieth- and twenty-first century works have enjoyed a similar longevity, but few or none of them have stemmed so exclusively from the creativity of one individual, and yet become so familiar, day by day, over a period of five decades.