Politics

How Hong Kong’s Struggle Came to Britain

Conflict is brewing between Hongkongers who have made the UK their home and a Communist Party that wants to make the UK its vassal.

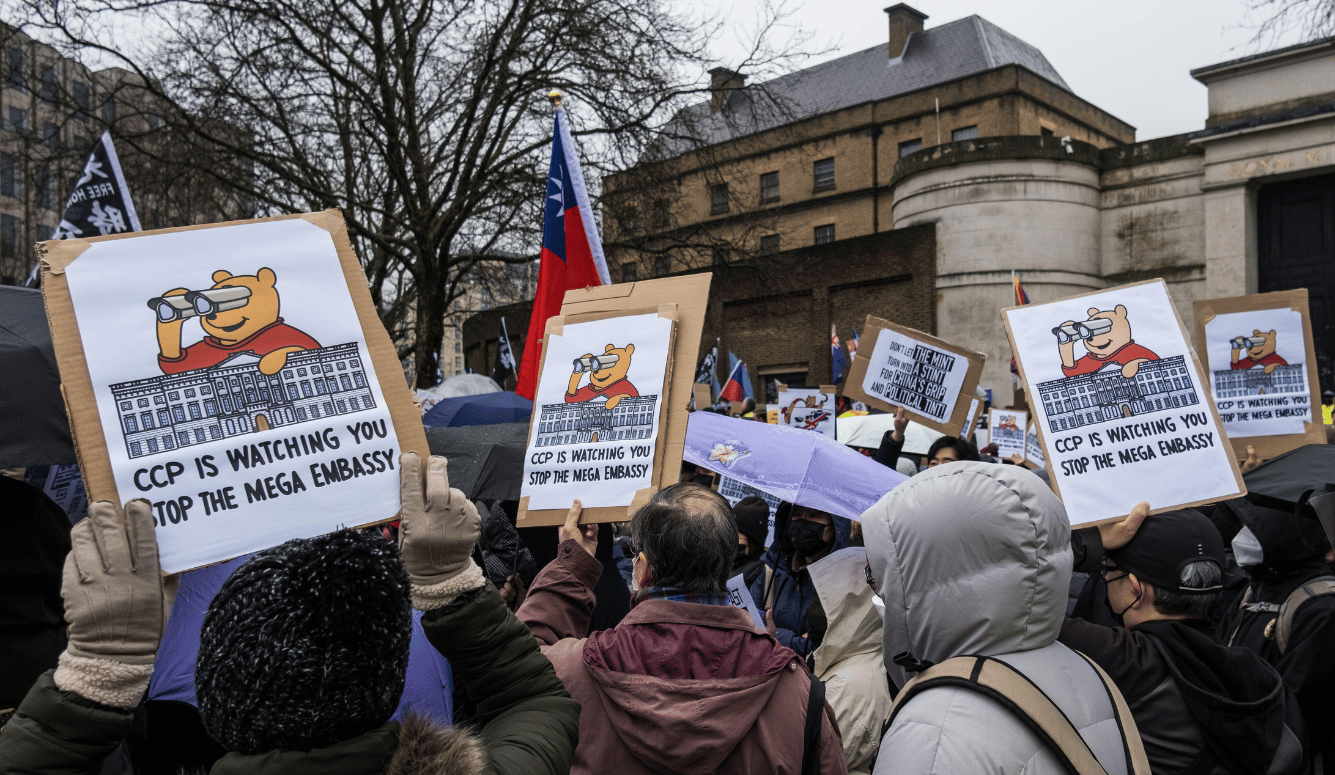

London isn’t much like Hong Kong. The cold grey drizzle, the cobbled alleys, the colour-palette ethnic makeup—no one could confuse it with the typhoons and wet markets and densely packed skyscrapers of Asia’s Vertical City. But on the afternoon of Saturday 8 February, the London borough of Tower Hamlets witnessed scenes that certainly evoked Tsim Sha Tsui in the sweltering summer of 2019. Hundreds of Hongkongers crammed the streets outside the old Royal Mint, blocking a police van that was attempting to transport two of their fellow protesters to the nearest police station. A phalanx of officers faced off against the protesters, roaring at them to “Get back!” The crowd chanted: “Release! Release!” Perhaps inevitably, a lone voice could be heard shouting at the police: “Are you working for the CCP?”

I had turned up knowing that drama was likely, just because of the sheer numbers expected. Estimates suggest there were 4,000 in attendance; when I asked a policeman for his guess, he reckoned 5,000. I saw flags proclaiming China’s various and ever-growing national independence movements—East Turkestan, Tibet, Southern Mongolia, “Cantonia” (the latter a new one to me: it appears that those particular separatists represent the southern province of Guangdong). But one group was dominant. Everywhere I looked, I saw the Black Bauhinia: pro-democracy protesters’ striking piratical variant on the flag of Hong Kong.

The protest had been organised because the Chinese Communist Party plans to build a national embassy at Royal Mint Court, giving rise to concerns about espionage and the illegal detention of dissenters. There is also concern over the practicality of the site. “In the event that more than a relatively small number of protesters attend the location,” warned Chief Inspector David Hodges back in December, “they will highly likely spill into the road … a major arterial junction … [with] over 50,000 vehicle movements per day.”

Saturday’s gathering aimed to prove Hodges correct.