Politics

Trump and the DEI Counter-Revolution

Civil-rights law made the DEI world; civil-rights reform can unmake it.

A full audio recording of this piece is available below.

The Trump administration’s opening policy blitzkrieg (on day one alone: 48 “presidential actions,” a record 24 Executive Orders, and 78 past executive orders revoked) has touched many different policy areas, but none more powerfully than DEI. Eliminating the “divisive and dangerous preferential hierarchy” created by “the injection of ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ (DEI) into our institutions” was indeed listed as number one of three policy priorities announced on President Trump’s first day in office (ahead of immigration reform and combating “climate extremism”).

The boldness of Trump’s anti-DEI initiative is indicated by three actions that have surprised even conservatives who have tracked these issues closely (myself included).

The boldness of Trump’s anti-DEI initiative is indicated by three actions that have surprised even conservatives who have tracked these issues closely (myself included). First, Trump revoked Executive Order 11246 (and other related steps), a move that struck an unprecedented blow against affirmative action and eliminated federal support in place since 1965. Second, he eliminated—not reformed—all federal DEI offices and officers in one fell swoop (something not even red states had ever contemplated). Third, he fired two of the three Democrats who serve as commissioners on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, thereby rendering that supposedly independent body incapable of pushing back against the rest of Trump’s anti-DEI efforts for the foreseeable future.

The penetrating power of these three measures is matched by the broad scope of the Trump government’s anti-DEI efforts. Summarising it in detail would take up too much space here, but so far I count nine executive orders issued since 20 January. Of those nine, four deal with antisemitism and the status of transgender persons; the remaining five take aim at “DEI” in its various registers and in different contexts. (Two other orders, one related to free speech and another rescinding 78 past executive orders, also make contributions to the anti-DEI cause.) Narrower anti-DEI initiatives emanating from individual federal agencies are by now too numerous to count.

How effective will Trump’s legal assault be? The dominant interpretations of DEI and radical progressive ideology set forth in books today focus on the causal role of bad ideas and other “cultural” factors: cultural Marxism (Christopher Rufo), postmodernism (James Lindsay and Helen Pluckrose), or social-justice activism manifested as some strange new Puritanism (Andrew Doyle) or other quasi-religious impulse (John McWhorter). If these interpreters are correct then, regardless of how decisive they are, the actions of the Trump administration are superficial and doomed to fail unless accompanied by some broader intellectual and cultural movement to change Americans’ hearts and minds. That latter campaign does not seem to be forthcoming—and, to be honest, most of today’s anti-DEI activists seem neither equipped nor inclined to do that kind of work.

But there is another school of DEI interpretation—advanced by authors like Richard Epstein, R. Shep Melnick, and Christopher Caldwell—that emphasises the causal power of politics and law. According to this view, DEI is the consequence of the civil-rights revolution broadly construed and of the contours of anti-discrimination law in its particulars. If this account of things is correct, we have every reason to think that the Trump administration’s actions are going to change the landscape of democratic life for the long haul.

Much is at stake in this question. Populist frustration has put its finger on real problems. The term “wokeness” identifies our hypersensitive, invasive, censorious, punitive, and pedantically moralising social and political order—a scheme that divides groups against one another in the name of “social justice.” Its questionableness is signalled by the many ways it breaks with our liberal-democratic constitutional tradition: it champions the identities of groups, not the rights of individuals; it obliterates the boundary between public and private; it harnesses the state to legislate morality, not to protect liberty; it demands respect and is dissatisfied with mere toleration; and it stirs people up where the liberal tradition tries to calm them down. It has upended our understanding of something as basic to human life as “sex” or “gender,” and in political initiatives like the 1619 Project, would make contempt for modern life a kind of virtue.

If DEI and its pathologies are the unintended consequence of anti-discrimination radicalism (civil rights as interpreted by the Left), then nothing is more urgent than a program of civil-rights reform.

If DEI and its pathologies are the unintended consequence of anti-discrimination radicalism (civil rights as interpreted by the Left), then nothing is more urgent than a program of civil-rights reform. Such a program is, in effect, what Donald Trump has launched in the first days of his second term. Though the connections between DEI and civil-rights law are not immediately obvious, the presidential actions of 2025 are best understood as taking aim at vital pillars of the Left’s interpretation of the war on discrimination.

Here is an experiment for social scientists: to what extent will the changes in civil-rights law and politics, beginning with the Trump administration’s 2025 policies, change democratic life—culture, ideas, mores, and social institutions? The next thirty or forty years ought to provide lots of evidence for the battle among competing interpretations of wokeness. Is it a product of ideas or of civil-rights law and politics? My money is on the latter.

Part I: DEI and Civil-Rights Politics

Two objections to the above claims will be raised. First, is it really true that these early Trump policy-reform pronouncements, even if implemented, will usher in a significant and lasting alteration of all of civil-rights law and politics? Second, and more basically, why should we think that DEI dogma is the product of civil-rights law and politics and not something else—intellectual history, cultural Marxism, and so on? Addressing these questions will usefully illuminate our situation and prepare us to think about future developments.

It makes sense to begin with the question of contemporary progressivism’s relationship to civil-rights politics. I have addressed this at greater length elsewhere, but one can summarise the whole in relatively brief terms with reference to two broad expansions of the civil-rights regime advanced by the Left, or two different aspects of progressive zeal that went well beyond anything in the original text of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The 1964 Act banned overt acts of discrimination by government in public gathering spaces (Title II, covering “public accommodations”) and in employment decisions like hiring, firing, and promotion (Title VII). Later developments went well beyond such measures, however. First, the 1964 Act emphatically did not embrace any kind of explicit group-equality policy (in fact, it explicitly prohibited it); second, nowhere did it ever contemplate anything approaching cultural indoctrination or other overt projects of social engineering.

Reforms in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, led by the Left but generally acceded to by the Right (evident in a series of important Supreme Court opinions of these years authored by conservative Supreme Court Justices), exploded the original meaning of the law in both of those directions. Claims for tangible group equality, in affirmative action and other policies (voting rights and “disparate impact”) aimed to do something about persistent gaps in income, jobs, education, and so on between blacks and whites, women and men, and the like. Anti-discrimination law thus became a tool for a large-scale redistribution of wealth and other tangible goods along group lines—what one of Trump’s executive orders refers to as an “identity-based spoils system” (EO 14173).

A second, more complicated set of practices and policies were “cultural”—involving civil-rights policies designed to change what we say, how we think, and how we relate to one another in “society” and in the sexual arena. It is especially this side of the Left’s interpretation of the war on discrimination that has become so hated in today’s populist upsurge.

Outlining both of these dimensions of what the fight against discrimination became will prepare us to see how, in taking aim at the civil-rights Left’s group-redistribution program as well as its cultural efforts, the Trump administration’s reforms go to fundamentals.

Group-Equality Politics

Political exertions through law have always been central to the Left’s group-equality and redistribution efforts. It’s true that group-redistribution measures exist outside of government (in many private-sector practices, like the Democratic Party’s delegate selection rules, for instance). But any project to bring about broad group equality, public or private, is the kind of thing that cannot even be contemplated without assuming some forceful deployment of real political and legal muscle.

This battle began as soon as the 1964 Act was passed. The quickest way to tell this somewhat long and complicated legal-political story is with reference to six bundles of policies that transformed the civil-rights revolution into a program of the group-based redistribution of wealth, jobs, and education. Three of these sets of policies deal with affirmative action in employment.

First, since 1965, the lure of federal-government contracts has been used to support affirmative action for private businesses (Lyndon Johnson’s Executive Order 11246, enforced by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs). Begun by Johnson, but perfected under Richard Nixon, this federal effort to induce large corporations to buy into affirmative action (by reporting on the racial composition of their workforces, and setting “goals and timetables”) was a characteristically semi-official, semi-voluntary policy requirement that went beyond (and indeed contradicted) the text and spirit of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But it was upheld in 1971 and subsequently by the federal courts and was never revoked (until now) by any Republican President. Promoting affirmative action by way of government contracts has likewise been supported by Congress in statutes and budgetary provisions using “minority set-asides” (supported by the Offices of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilisation pervading the federal government).

Second, since 1971, the federal government has itself been an affirmative-action employer, when the Civil Service Commission caved to pressure from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (Nixon contributed here as well, with EO 11478.)

Third, in 1979, the Supreme Court held that affirmative action in the private sphere does not fall afoul of the Constitution or civil-rights law.

These three policy steps are obscured to some degree by the role of the courts and the executive branch in making affirmative action a reality in American life (most members of Congress also supported it, but they could never have passed an Affirmative Action Act without paying a heavy price at the polls). Though the text and basic principles of American civil-rights law officially reject the idea of group redistribution in theory, it has long been entrenched in practice with the support of a more convoluted legal architecture.

The fourth bundle of important affirmative-action policies affects admissions in higher education; where state (public) university policies have been the central players. A diversity loophole, created in the 1978 Bakke case (and affirmed in the 2003 Grutter decision), gave universities a green light to award preferential treatment to students from (some) minority racial and ethnic groups. This area of policy has already been dealt a decisive blow in the 2023 Supreme Court decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard.

Fifth, group-equality measures in voting (so-called “max-black” and “max-Hispanic” districts) have been entirely the creation of law.

Finally, sixth, the notion of “disparate impact” discrimination (the idea that group inequalities are themselves evidence of illegal “discrimination”) has been a left-wing tool of civil-rights enforcement to be wielded by government (no “private right of action”) since at least 1971. Using the 1964 Act’s Title VI threat to cut funding, investigations by federal agencies applying a disparate-impact standard extended the reach of this view of discrimination into many different areas of policy all at once. In recent years, “equity” has become the term used to denote such measures. That ideal was central to the Biden administration’s “whole of government” equity agenda and its creation of “Agency Equity Teams” in all of the agencies of the federal government.

These efforts, and the debates about them, have been around since the very beginning. It might seem odd to say, therefore, that they are important to today’s complaints about “wokeness.” But as we shall see, it is impossible to disentangle the more immediately hated cultural features of progressive doctrine built into civil-rights law from the question of group equality. In any event, it is telling that nobody is saying now that attacks on affirmative action and disparate impact and the like are somehow beyond the remit of a campaign against DEI. One could say that Trump’s two-pronged attack is schooling us all by mapping in rough outline the broad phenomenon underlying populist resentment.

Cultural Efforts Imposed by Law

The legal story behind the cultural features of contemporary progressivism is a bit more complicated, but not impossibly so. And it is important to clarify the legal-political basis of this phenomenon because most of the energy of populist anger and frustration resides here.

The heart of this story is how employment discrimination law (Title VII of the 1964 Act) was re-interpreted in the 1980s and 1990s.

The heart of this story is how employment discrimination law (Title VII of the 1964 Act) was re-interpreted in the 1980s and 1990s. The first step was the identification of something called “hostile environment harassment.” This concept, and especially sexual hostile environment harassment, radically transformed the anti-discrimination project. All at once, anti-discrimination enforcement became, of necessity, a matter of policing what we say and think and how we treat one another in our interpersonal and social relations, which our liberal tradition had always kept separate from the state.

This enlargement of the fight against discrimination was magnified again when employer liability for this newly identified and newly condemned set of social harms was expanded to an extraordinary degree. Employers became responsible, not just for their own discrete discriminatory employment actions or policy decisions, but also for anything and everything that happened in the ballpark of harassment (including offensive statements) between employees—and suppliers and contractors and customers—in the workplace.

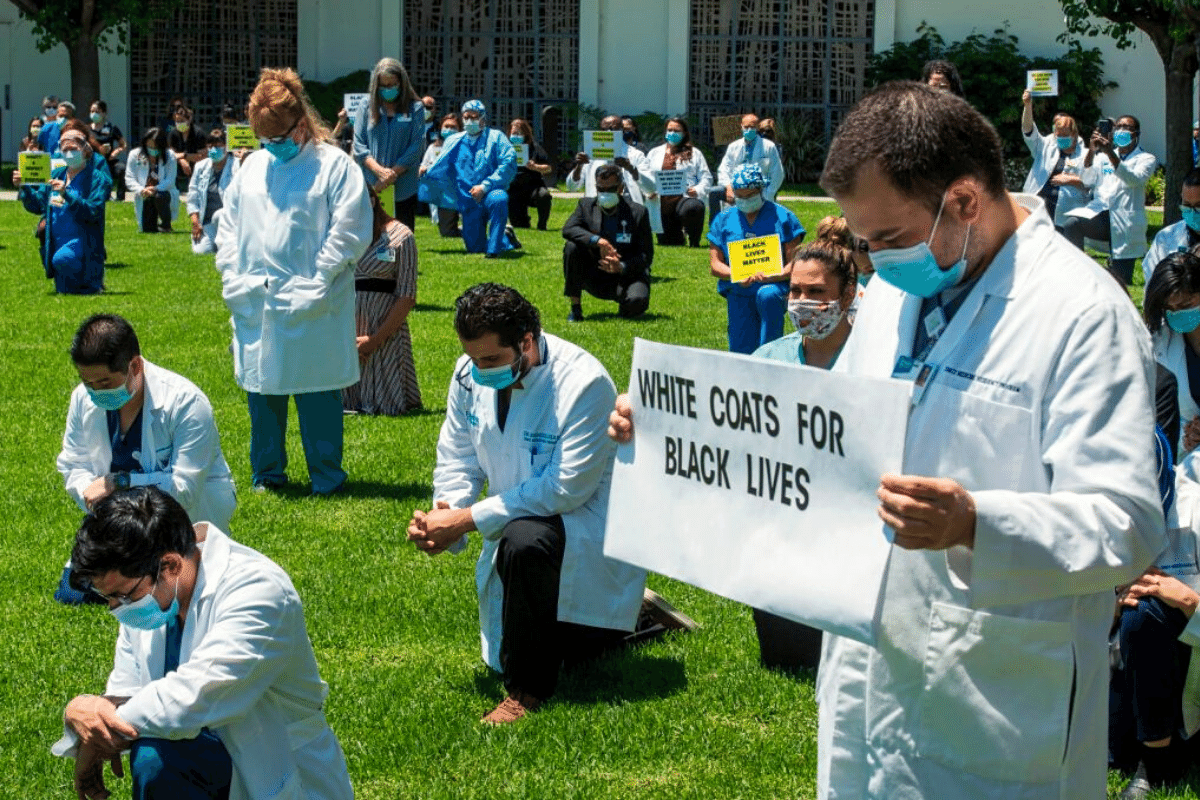

Begging the courts for some safe harbour in this perilous new sea (lawsuits in the millions, reputational harm), employers were told that they would be granted some mercy if they could show that they had undertaken “preventive and corrective” measures like diversity training (“preventive”) and firing miscreants (“corrective”). Though it is somewhat hidden, we can point here to a direct causal link between the law and progressive practices in the workplace.

All of that had been put into place by 1998, when the Supreme Court announced its “Ellerth-Faragher employment liability test.” Naturally, this framework was embraced by employers. They went along with it “voluntarily,” but they were incentivised to do so by a legal scheme that no one in 1964 could have foreseen. Employers then became the privatised enforcers of anti-discrimination policing that obliterated the public-private divide. Envisioning new possibilities of “institutional citizenship,” academics describe a brave new world shaped by “the legalisation of the workplace” and “the managerialization of law.”

The immediate and direct result of this legal order was a regime of hypersensitivity, pedantic moralising, and censorship; a program of invasive micro-policing of daily life, and of our interpersonal relations. This was all enforced by our fellow-citizens with draconian sanctions (above all, loss of employment) and no recourse to due process. It is this poisonous brew that is widely despised today as “wokeness.” When people disparage DEI today, they generally mean the welter of rules, practices, institutions, and personnel (“officers”) called into being to carry out this new political program of cultural and social engineering.

The most visible incarnations of DEI are to be found in DEI training, and in DEI offices and officers. But this is just the tip of a large iceberg. Offices of Equal Opportunity and myriad other institutions (Diversity Task Forces, Bias Incident Response Teams, Workplace Responsibility Committees, Equity Teams, and so on) work under the supervision of the newly necessary agents of the new order (Equal Opportunity officers, Title IX officers, the ubiquitous “Chief Diversity Officer”). These individuals and bodies are charged with undertaking a wide range of tasks, including formulating and publicising internal policies, assessing the status or climate of the institution and those operating within it, monitoring bias-reporting systems, fielding discrimination and harassment claims, conducting investigations, keeping records, and meting out consequences. Though they have been put in place by the semi-voluntary workings of employment-discrimination enforcement, they have quasi-official status, authority, and weight. Non-compliance at any step may be cause for corrective firing and other punitive/disciplinary actions.

A parallel legal order in the world of education borrowed from these developments in employment law to impose a similar regime in our colleges and universities. Its enforcement machinery is distinguishable only because it is more aggressive, since anti-discrimination law affects higher education twice—employment discrimination law on one hand and myriad civil-rights educational regulations (Title IX, accreditation standards, etc.) on the other.

Once you start to look for it, it is actually fairly easy to show how civil-rights law inserted progressive dogma into all of our institutions of employment and education, making it a pervasive and powerful force. These legal-political beginnings have shaped other democratic social structures (the “long march through the institutions”) and poisoned the modern democratic soul, shaping individuals and their moral outlook and mental categories.

Citizens look up to the law; they respect its authority and fear its sanctions; they generally feel incapable, in their weakness, of resisting it.

This is what Aristotle meant when he wrote that politics is “architectonic.” Citizens look up to the law; they respect its authority and fear its sanctions; they generally feel incapable, in their weakness, of resisting it. Seeing the victory of a broad and revered political development and hearing its moral claims repeated everywhere (the new logic of identity, inclusion, recognition, respect, equity, and so on), many people come to think its demands define justice. Politics is causally powerful because most people are decent citizens who wish, on some level, to do what is right. (That might sound naive and moralistic; it is meant only to be a statement of fact.) This is why many Americans—good citizens affected by this most powerful democratic moral-political-legal juggernaut of the 20th century—became living proof of the power of the anti-discrimination regime as interpreted by those who had pushed its logic and lessons the farthest.

From Wokeness to Anti-Wokeness

But not all Americans—or not all of them, all of the way, or all of the time. The American soul is in fact deeply divided on these questions. That is the most important meaning of anti-woke anger and concern. Wokeness produced anti-wokeness in two different ways. Two large obstacles have always stood in the way of the Left’s anti-discrimination radicalism and in the past few years they have asserted themselves in ever-more pronounced ways.

First, civil-rights extremism has exposed the lingering hold of our liberal-democratic constitutional order. A people raised under the principles, politics, and institutions of the Enlightenment has not entirely forgotten its devotion to the cause of liberty. Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, due process, the idea that legislating morality is wrong—all these ideas and more have been called back into service to help combat political extremism. (This is why attacks on liberalism by postliberal authors like Patrick Deneen could not be more misguided.)

Second, members of groups identified as the past perpetrators of discrimination (whites, men, straights, Christians—what the law calls “majority groups”) have become frustrated with a world that condemns them and their past and that can find nothing to admire in their heroes or history (the 1619 Project, statue removals, and so on). It is the members of these groups whose jobs, wealth, educational opportunities, and other benefits must be sacrificed if group redistribution is to be effected. These majority groups have long felt that enough is enough, but books by authors like Jeremy Carl are now starting to say so without embarrassment.

Anti-wokeness therefore represents a protest by something like a majority of our democratic population in the name of the political tradition that has defined our public life for more than two centuries, and in the name of their perceived economic and cultural self-interest. As inchoate as complaints about “wokeness” may sometimes be, they represent extremely powerful political forces in the aggregate.

Part II: The Depth and Breadth of Trump’s Anti-DEI Campaign

Trump’s election on an anti-DEI platform, the anti-DEI reforms he has introduced, and the disarray of Democrats in the face of these developments would all seem to prove that the powerful spell cast by the civil-rights revolution on American politics has been broken. But are Trump’s reforms really shaking up the foundations of civil-rights politics for the long haul? There is a lot at stake in that question, especially if it is true (per Aristotle) that significant changes in the political order are likely to alter democratic life and the meaning of democratic citizenship in a broad way.

That is an easy call. By any measure, Trump’s reforms are already transforming the landscape of anti-discrimination politics at a fundamental level. American civil-rights politics are unlikely to ever be the same after January 2025. But how are we to measure Trump’s actions so far—which, after all, only amount to a couple of weeks’ worth of policy announcements—and to gauge whether they will have a lasting effect on American politics and life?

The two species of civil-rights politics discussed earlier bear further examination—civil-rights group-redistribution initiatives and the Left’s anti-discrimination cultural efforts. Each of these represents something large; hitting both of them simultaneously and effectively would necessarily have broad consequences. The main question would then be about the effectiveness of the measures being undertaken. We have enough information now, it seems to me, to say that we should not underestimate the significance of what the Trump administration is doing.

The Cultural Dimension

The Trump administration’s abrupt elimination of all of the federal government’s DEI offices and personnel—to be followed by efforts to bring about something similar in the private sector—represents a massive shock to the system that will be felt for a generation or more.

As we have seen, under the guidance of the Left’s civil-rights politics, federal law had been instrumental in establishing, in the workplace and in the educational sphere, a semi-voluntary, semi-official, and extremely complicated web of institutions, personnel, and ideas to advance a pervasive and penetrating program of cultural, social, and personal change. While it lasted, this maze of anti-discriminatory activity was ambitious and inventive and energetic, but the Trump administration is now revealing that its institutional foundations were always weak and vulnerable.

The administration’s main strategy for dealing with all of this (laid out in detail in EO 14151) is simple and direct. Trump’s order calls upon “[e]ach agency, department or commission head” to “terminate ... all DEI ... offices and positions (including but not limited to ‘Chief Diversity Officer’ positions),” all “DEI ... positions, committees, [and] programs,” all “‘equity’ ... initiatives or programs.”

Eliminating the DEI offices and officers affects the cultural side of DEI by halting all the cultural work done by those offices and those individuals within the federal government—the tasks of monitoring and policing anything in the ballpark of discrimination, of assessing the “climate” of federal agencies, of teaching everyone within it the true path, of publicising and reporting on the good work being done (or, just as important, the failure of those under the sway of the regime to measure up).

Unsurprisingly, the orders do not concern themselves with enumerating those tasks in detail. Where DEI practices are targeted, they are named in a very general way. Gone now are “all ‘equity action plans,’ initiatives, or programs,” so too all “DEI ... services [and] activities.” Diversity training and “training policies” do receive special (negative) attention: “Federal contractors who have provided DEI training or DEI training materials to agency or department employees” must now be reported. Simply by removing those who enforced its norms, and disavowing the idea of DEI in a general sense, the Trump orders strike a powerful blow to the invasive, preachy, punitive, and censorious dimensions of anti-discrimination enforcement within the federal government.

The evisceration of DEI here goes far beyond anything attempted by red states, which have taken steps in recent years to try to rein in DEI offices and officers at the state level without simply eliminating them. But conservatives involved with such initiatives have long complained that the bureaucracy is adept at evading their reach. Those in charge of the Trump anti-DEI push clearly learned from these earlier efforts. Not only did they strike more forcefully, but the orders also explicitly warn those carrying them out to be on the lookout for any attempts to “misleadingly relabel” DEI (EO 14151).

Another key chokepoint is funding. Likewise targeted for “termination” are all “‘equity related’ grants or contracts” and all “DEI ... budgets and expenditures.” Agencies must now provide a list of all “Federal grantees who received Federal funding to provide or advance DEI” and will henceforth be required to prepare reports on the “economic and social costs of DEI.” Connected to this, “employment practices [and] union contracts” are to be purged of all DEI content, as are “DEI ... performance requirements for employees, contractors, or grantees.”

The cultural side of the anti-DEI campaign focuses first on the conduct of the state, a blueprint of cultural counter-revolution within the institutions of government. But the Trump administration is clearly aiming to extend these efforts into the private sector as well. As is already indicated in some of the language quoted above, federal (private) contractors and grantees are subject to this aspect of the anti-DEI orders as well. That other steps to limit DEI’s hold on private life are contemplated is indicated with breathtaking audacity in EO 14173:

[T]he Attorney General, within 120 days ... shall submit a report ... containing recommendations ... to encourage the private sector to end illegal discrimination and preferences, including DEI. The report shall contain a proposed strategic plan identifying ... [t]he most egregious and discriminatory DEI practitioners in each sector of concern. ... [E]ach agency shall identify up to nine potential civil compliance investigations of publicly traded corporations, large non-profit corporations or associations, foundations with assets of 500 million dollars or more, State and local bar and medical associations, and institutions of higher education with endowments over 1 billion dollars.

If politics is architectonic, then this is Trump’s own “long march through the institutions.” The private sector is watching and all of these legal steps will only accelerate the widely reported retreat of corporate America from its DEI commitments (to say nothing of state and local government, especially in red states).

If politics is architectonic, then this is Trump’s own “long march through the institutions.”

Education, public and private, is also the target of anti-DEI efforts in the cultural sphere. This is most clear in EO 14190, which deals with K-12 education. Here, we see the resurrection of what was termed “divisive concepts” in a 2020 Trump executive order (EO 13950, rescinded by Biden)—now relabelled “discriminatory equity ideology.” By banning these teachings in public and private education, and by promoting an alternative to it (“Patriotic Education”), the Trump administration engages in cultural politics in a very direct way. (Similar efforts appear in EO 14185, pertaining to the military.)

Much more can and likely will be done in the educational domain. One striking feature of the executive orders issued thus far is the omission of a broad anti-DEI directive for higher education; while many of the nine anti-DEI orders released to date touch on higher education, they either do so narrowly or to deal with questions pertaining to some one group (antisemitism and transgender claims, for instance).

There are reasons to wonder about the effectiveness of the divisive-concepts bans, in particular. This is a ham-fisted tool and their impact will not be so immediately dramatic and apparent and effective as those discussed above (or the attack on affirmative action summarised below). That is in part because, as similar red-state efforts undertaken during the past few years have proven, divisive-concepts bans are vulnerable to free-speech challenges, most clearly demonstrated by the defeat of Florida’s Stop WOKE Act in federal court. This concern appears in the form of various reassurances about freedom of speech that appear in some of the anti-DEI orders. More generally, because they touch very openly on what people are supposed to think and say, they smack of illiberalism and are generally unpopular.

These caveats aside, the current shock and awe approach of the Trump government to the offices, officers, activities, and programs associated with the Left’s anti-discrimination politics is undoubtedly having a broad effect. The acid test, however, is whether or not it will weaken the hold of the Left’s interpretations of anti-discrimination law and the manner in which the law is enforced. These are crucial because, as we have seen, the hated cultural radicalism originated in them.

There is evidence in the Trump orders that some effort along these lines is indeed being made. First, the Left’s interpretations of the law are being discredited and made suspect. Here is a potentially good effect of the divisive-concept bans, were they somehow re-conceived as efforts to reform anti-discrimination law. Attacking ideas like “unconscious bias” and “privilege,” the government’s divisive-concepts bans take aim at core assumptions of the Left’s interpretation of the fight against discrimination (attacking these concepts in the law raises no free-speech objection).

Much more fundamentally, the Left’s interpretation of the law is being displaced by a rival interpretation of civil-rights statutes and a colourblind approach to non-discrimination and “equality of opportunity for all Americans” (EO 14173). This can be found on every page as the orders repeatedly appeal to our “civil-rights laws.” The substance of this view of the law may be discerned by its consistent characterisation of Biden-era positions as “illegal racial discrimination under the guise of ‘equity’” and in its repeated prohibition of “discriminatory and illegal preferences” (EO 14173). At one point, developing a more detailed account of anti-discrimination law’s proper meaning is called for explicitly, in monthly gatherings of top officials meeting to “formulate appropriate and effective civil-rights policies for the Executive Branch” (EO 14151).

Enforcing and reinforcing a moderate and sound interpretation of civil-rights law would have the systemic effect of altering the meaning and tone of civil-rights enforcement within the federal government and beyond. That broad consequence would be at least as important as everything that Trump has already been able to achieve. It is true, however, that DEI offices and officers do not comprise all of the federal government’s civil-rights effort. Offices of Civil Rights or their equivalent exist in every agency of the federal government, and will still exist under the orders issued to date. Those offices are necessary and have statutory commitments that cannot be altered significantly without input from Congress.

How exactly the assault on DEI and “discriminatory equity ideology” is related to the necessary and legitimate enforcement of civil-rights law is left unclear. Crucially, by focusing mainly on offices and officers, the anti-DEI effort need not get mired in the details of DEI practices, some of which might seem to lend support to the existence of some offices and officers, insofar as they might seem to be tied to civil-rights enforcement. That is a bold stroke and indicates great political flexibility in what the Trump administration is doing in these early days.

The changes surveyed here will be hard to undo. In this assault on the cultural dimension of the Left’s civil rights vision, DEI’s own legal and institutional irregularities contribute to its demise. Created mainly by semi-official, semi-voluntary, and indirect modes of employment-discrimination enforcement, their legal vulnerability has always been hidden in plain sight. What is not strictly mandated by the law may be eliminated by law. Moreover, because it was established largely by executive decisions, and not by statute, DEI’s institutionalisation has always been subject to immediate deconstruction by nothing more than executive command.

The legal vulnerability of DEI was hidden by its longstanding political invulnerability. So long as Democrats were in power, its flexible legal foundation helped to expand DEI. Likewise, until now, Republicans, beholden to and cowed by the moral power of the civil-rights revolution, were unwilling to question its authority. That includes Trump, by the way, who had long supported affirmative action and gay marriage, and did not begin to turn against DEI (“divisive concepts”) until the end of his first term.

But 2020 was a turning point. Republicans, buoyed and steeled by populist anger, began to see that limited government alone would not be strong enough to confront anti-discrimination extremism. Using red states as “laboratories of democracy,” conservatives learned how to use the machinery of the progressive state against itself. The stage was set for a day when Republicans controlled the White House, Congress, and the Supreme Court.

Group Equality, Too

On the group-redistribution front, Trump has hit even harder, if that is possible, and in policies that are clearer and more precisely crafted. The administration’s orders assault every one of the group-equality policy bundles mentioned earlier, with the sole exception of minority group voting policy. For the first time, the demise of affirmative action and “disparate impact” (and the Left’s interpretation of “equity”) seems truly to be within reach.

The federal government’s own affirmative-action employment efforts end with these orders, especially in Executive Order 14170, titled “Reforming the Federal Hiring Process and Restoring Merit to Government Service,” which calls for a “Federal Hiring Plan” that will “prevent the hiring of individuals based on their race, sex, or religion.” The end of affirmative action is also indicated by two other executive orders: “Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing” (EO 14151) and “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity” (EO 14173).

These orders go a long way towards ensuring that federal contracting power will no longer be used to support affirmative action in the private sector. In perhaps the most astonishing step taken in all of Trump’s anti-DEI initiatives, his Executive Order 14173 revokes Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246 (and several subsequent orders that strengthened it), the lodestone of American affirmative-action policy. Here, in one bold stroke, sixty years of executive orders, supplemental policies, and guidance documents, and federal court precedents interpreting 11246 and its progeny die a sudden death. Ronald Reagan contemplated this step but drew back—as did every other Republican president, including Trump in his first term.

Biden’s “whole of government” “equity agenda” and the “Equity Agency Teams” he created in all federal government agencies are no more.

Likewise, the government’s embrace of “equity” and “disparate impact” has been demolished. Biden’s “whole of government” “equity agenda” and the “Equity Agency Teams” he created in all federal government agencies are no more. Within sixty days, “each agency, department, or commission head” must take steps to “terminate ... all ‘equity action plans,’ ‘equity’ actions, initiatives or programs, ‘equity-related’ grants or contracts; and all DEI or DEIA performance requirements for employees, contractors, or grantees.”

So far as I can see, the terms “disparate impact” and “disparities” are never even used in these orders (“affirmative action” is only used once), but the failure to use that language should not be taken as a sign of non-confrontation. Indeed, that view of things is now simply rejected as “illegal discrimination,” a phrase that appears over and over again in the titles and text of these executive orders. Gone too are several Biden executive orders advancing governmental group-equality/equity initiatives tailored specifically to the interests of blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, Asians, and LGBTQ groups.

This is not just a purging of government affirmative action and “equity”; the power of government is being harnessed to reshape the private sector with vigour. The reach of these efforts into the private sector (already indicated by the demise of EO 11246) bears emphasising.

All “references to DEI and DEIA principles” are to be “excise[d]” “from Federal acquisition, contracting, grants, and financial assistance procedures.” Not only that, but now the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), long a citadel of the anti-discrimination Left, will be used to police anything smacking of affirmative action: where once government contractors had to report the racial (etc.) composition of their workforce, henceforth all “Federal contractors and subcontractors” will now be required to “certify that [they do] not operate any programs promoting DEI that violate any applicable Federal anti-discrimination laws.” (Apparently, government paperwork never goes away, though its substance may be radically altered.)

Similarly, the orders highlight “litigation” as another important strategy (EO 14173) to go after affirmative action and equity in the private sector. We will be hearing much more about the reach of these initiatives into private life since Trump’s march through the institutions is concerned at least as much with identifying “egregious and discriminatory” affirmative-action efforts in “publicly traded corporations, large non-profit corporations or associations, [and] foundations” as it is with policing the cultural aspects of the Left’s anti-discrimination zeal.

Higher-education affirmative action is not (yet) the subject of any one executive order (several anti-DEI orders affecting K-12 have been issued, so one assumes a similar package for higher education will be forthcoming soon). But one order does mandate compliance with the Supreme Court’s 2023 anti-affirmative-action decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. EO 14173 commits the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights to policing “all State and local educational agencies that receive Federal funds, as well as all institutions of higher education that receive Federal grants or participate in the Federal student loan assistance program” to ensure that they “comply” with the SFFA decision. As noted above, the same order targets non-compliant “institutions of higher education with endowments over 1 billion dollars” for special “civil compliance investigations.”

Republicans under Trump have learned how to harness the power of government to affect broad political change. Group redistribution in America was made by law and now Trump is showing how law can unmake it.

The Two Arms of Civil-Rights Radicalism

There are other measures not included in my summary, but they will not be as important as the two broad strategies of the Trump government’s anti-DEI campaign emphasised here. Free-speech initiatives, wielded against DEI in many red states and advocated by groups long critical of DEI—like the National Association of Scholars (NAS), Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), and Heterodox Academy—do make an appearance in some of the orders, but not really as an anti-DEI strategy. Executive Order 14149, titled “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship,” might implicitly be used to fight DEI, but there is no direct mention of that possibility (the order focuses on government–tech censorship collusion).

Similarly, three of Trump’s nine anti-DEI orders deal with policies involving transgender persons. These are obviously in the ballpark of DEI, but they are all fairly narrow in their focus. Their limited range is indicated immediately by the fact that in none of them (and in no Trump order that I have seen) is any attention paid to related questions pertaining to gays and lesbians (gay marriage, for instance). There is almost no mention of issues pertaining to civil rights and women (the affirmative-action orders do mention “illegal discrimination and preferences” based on both “race and sex,” but otherwise the equality of men and women established by the anti-discrimination revolution receives not a word). In short, there is no reason to think that the outcome of the debate over the treatment of this one group will be as systemic in its effect as will be the very general alterations to civil-rights politics that I have discussed.

Something of real importance is revealed in the broad outlines of the Trump administration’s two-pronged attack on DEI. Does it go too far to say that these two dimensions of the Left’s radical interpretation of anti-discrimination politics reveal something about the essential truth of the fight against discrimination as such?

In 1964, the anti-discrimination revolution began by attempting to eradicate—or at least minimise—overt cases of individual and intentional discrimination in segregated schools, segregated restaurants and hotels (Title II), racist employment practices (Title VII), segregated housing, and the like. This was already an ambitious democratic project. It is a sign of how much has changed in the years since that, by our standards today, we might be inclined to view that original impetus as representing a limited set of aims.

But once that project was entrenched in law and accepted as gospel by the public, persisting group inequalities plausibly tied to past discrimination began to be viewed in a new light. What “discrimination” itself amounted to began to change; it was now understood to be something bigger and more deeply entrenched and harder to eradicate (systemic, societal, structural). That step, which happened immediately, was quickly followed by another redefinition of discrimination to expand its reach to the opinions we hold (“stereotypes”) and the things we say and do to one another in our everyday social interactions (“harassment”). Novel enforcement mechanisms (and offices and officers) were created to police these new norms.

In the concept of discrimination, Americans found a whole world of egalitarian concern that was never before recognised so clearly in the history of democratic politics. These expansions of the original idea of anti-discrimination happened so quickly and without real opposition that they suggest something necessary to the basic idea was being worked out (recall all the conservative Supreme Court Justices and Republican politicians who helped create the new scheme). What do these two expansions of the civil-rights revolution’s original meaning suggest? Aristotle once observed that all political disputes are about either money or honour. Civil-rights politics is a politics of redistribution and recognition.

More or less overnight, a program of redistribution and recognition became the authoritative template for thinking about democratic “group politics,” displacing an older system for managing group politics derived from our liberal constitutional tradition (individualism, toleration, separation of public and private—the logic of religious pluralism, of interest-group pluralism, and so on). In America, that older scheme had worked fairly well for a couple of centuries, except as it related to race. In the grip of a kind of moral upheaval that arose out of concern for the special case of American blacks, democratic peoples across the globe suddenly embraced the new order at roughly the same time. Shifting over to that new view of things was a momentous step in the broad trajectory of modern democratic life that nobody really intended or planned out in advance; a development, it must be said, that we do not really understand to this day.

How are these two faces of civil-rights politics related to one another? Which is primary, the redistribution of goods in the name of group equality (affirmative action) or efforts in the cultural, intellectual, and moral spheres and their psychological consequences (where DEI officers, diversity training, censorship, corrective firing, and so on do their work)? Is one the end, the other the means? Do the latter point to the heart of things, the anti-discrimination Left’s “ideas” about justice plus the many exertions needed to make them stick? Or do those cultural efforts, as a kind of “deference politics,” merely serve to justify taking from some and giving to others? Was the point of all the monitoring and training and “preventive and corrective measures” ultimately intended to make majority groups pliant and willing to hand over the goods? (Social scientists ought to be tripping over one another to answer those questions, but I won’t hold my breath.)

Part III: Taming the Anti-Discrimination Regime

It is certainly true that civil-rights group redistribution efforts and the “cultural” exertions of the civil-rights order have worked to reinforce one another. That Trump has been able to hit both sides of the Left’s radicalism, and hit them hard, suggests that his government’s actions will have some kind of long-term effect.

The scope and scale of what Trump is doing is entirely unprecedented in the history of the post-1964 civil-rights order. Never before has there been any significant pushback against any important advance of the post-1964 civil-rights regime. Conservatives have often helped to extend that advance, but they have never hindered it. (School busing did die a slow and more or less quiet death, but that was a special case.) Anti-DEI is being institutionalised. The measures taken thus far in this two-pronged attack are already too big not to register in the broad scheme of things. Lasting changes are being made now that will not be unmade without some kind of effort that is unforeseeable at present.

To be sure, several years of similar (though generally much weaker) initiatives in twenty-plus red states, and especially the inventive and aggressive work of Ron DeSantis in Florida, prepared the way for Trump’s anti-DEI campaign. Those state efforts are now being strengthened by what the federal government is doing and we are sure to see even more ambitious state efforts in the near future. Presumably, these will now be undertaken with greater vigour and less hesitation. No matter what else happens, four years from now, stronger red-state policies will represent an important obstacle to any future pushback efforts, even if Democrats retake Congress and/or the White House.

At least as important, the Trump administration’s anti-DEI policy is backed by widespread popular support. (Did Trump help America discover anti-woke ire or did it create him?) Populist outrage is not an entirely reliable political force, but the 2024 election proves that it is not one to be ignored.

The obvious analogy is to 1954, when America’s “red scare” mania broke and was discredited, marked out clearly by Congress’s censure of Senator Joe McCarthy. Anti-communism before that moment was, it is important to recall, a bipartisan affair (John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon both came to prominence as communist-hunters after World War II). But then popular opinion shifted and anti-communist purges and blacklisting became discredited in the popular eye—even though anti-communism remained the more or less unquestioned cornerstone of all American foreign policy. (There are many interesting lessons to be teased out of this comparison.)

Will Democrats double down on defending DEI? That seems unlikely. Soul-searching by the likes of Bill Maher, Ruy Teixeira, James Carville, and Maureen Dowd about the price Democrats are paying for their diversity doctrines suggests that the future of the American Left will involve at least some rethinking of anti-discrimination zealotry. Indeed, the relative silence of not just mainstream Democrats but also the activist radicals is a surprising sign of how stunned the Left seems to be by the blow that progressive excess has taken in America. Even if the political fortunes of the Democratic Party are revived, it will be very difficult now for the Left to go back to the extreme posture of the recent past.

The most important change concerns Republicans. Until now, the default position of Republicans has been deference (willing or unwilling) to the moral sanctity of the civil-rights movement and all that followed from it, including, to some important degree, its most radical interpretation—as all the Supreme Court decisions on this matter written by conservative Justices attest. Indeed, until now, civil-rights politics has been something everyone has had to simply bow to. But now, under Trump, the Republican Party is openly criticising this consensus and assaulting it along a wide front.

Not only is Trump showing today that it is permissible to question aspects of radical civil-rights politics, he is also demonstrating that politicians who do so will be rewarded. By taking these bold steps, Trump has demonstrated that the anti-discrimination Left can be attacked frontally and effectively and at many points at once. These efforts seem to be redounding to the political advantage of the Republican Party. It is at least possible to imagine that, managed correctly, civil-rights reform could provide the basis for a long-term realignment of the political parties putting the Republicans in charge for a generation.

What this new departure offers—if, to repeat, it is managed correctly—is an opportunity finally to stop and think about the fight against discrimination. If Republicans are smart about it, they might create a world in which questions of civil-rights policy are treated like every other kind of policy—where weighing the pros and cons of every side of every issue is to be expected (and won’t get you cancelled or fired).

At the very least, opposition to the Left’s diversity, equity, and inclusion agenda has now been firmly established as an accepted part of normal political debate in America. Criticism of civil-rights extremism will be with us for the foreseeable future.

A New Era of Civil-Rights Reform?

What the current moment suggests, above all, is that we have reached a moral tipping point. The enchantment—no, the illusion—of the moral purity of civil-rights politics is now being successfully challenged in a spectacle, the simple and crude lessons of which do not require much elaboration or defence (again, the fate of “McCarthyism” is instructive).

It is important to say, however, that this challenge to a certain view of civil-rights idealism has been undertaken in the name of civil rights—but of civil rights understood in a different way. That is not a matter of interpretation; appeals to “our civil-rights laws” are all over the Trump orders. This is important and bears further examination. If we are lucky, Trump will go down in history for ushering in an era of civil-rights reform.

There is more work to be done to get to the final step implied (but never quite made explicit) by the logic of what the Trump administration has begun. It is not obvious to everyone—yet—that opposition to “wokeness” is really opposition to the Left’s interpretation of anti-discrimination politics; and it is not yet obvious that the new stance being marked out represents a saner interpretation of civil-rights law and politics.

Conservatives, front-line critics of progressive extremism (NAS, FIRE, Heterodox Academy, etc.), centrist liberals, and the Trump administration all need to do more to say clearly that they are actually doing the work of civil-rights reform. Their manifest hesitation to do so, whether from free-speech monomania or moral anxieties about touching civil rights, ought to be cause for concern. If we want to fully exploit what the Trump administration has done, we will do so only if we face this large and difficult task.

All honour to the genius of the American people for discovering in “wokeness” the indispensable term of the hour. “Wokeness” discourse was essential in getting us to where we are today because it allowed us to say things that, in a veiled way, expressed powerful criticisms of aspects of civil-rights politics. The people in their wisdom did what the elites could not: they exposed the Left’s vision of anti-discrimination politics as being, if not naked, then only partly dressed—and not a little crazy.

The people in their wisdom did what the elites could not: they exposed the Left’s vision of anti-discrimination politics as being, if not naked, then only partly dressed—and not a little crazy.

But, because much “anti-wokeness” talk hesitates to state the true object of its own anxieties and frustrations, the time has come to set it aside. We need to be talking more clearly and directly about the civil-rights revolution, the fight against discrimination, the anti-discrimination regime, and the need to engage in the vital task of reforming it. (And not, then, so much about “cultural Marxism,” intellectual history, and so on.)

There are signs that the Trump administration is already very close to seeing its anti-DEI program as an effort of civil-rights reform. Over and over again, the orders invoke “civil-rights laws,” “Federal anti-discrimination laws,” and “the 1964 Civil Rights Act.” Measures aimed at “ending illegal DEI” are presented as precisely a way to “protect civil rights” and to preserve “the progress made in the decades since the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” The Trump administration is certainly right to say that this anti-DEI undertaking represents “the most important federal civil rights measure in decades.” Broadening such claims into a self-conscious campaign of coming to grips with what the civil-rights revolution has wrought, warts and all, could transform Trump’s efforts, now defined in somewhat ambiguous and hesitant terms, into a landmark turning point in the long history of liberal-democratic politics.

But there are reasons to doubt that this will happen. One is a certain lack of clarity about the main target of the Trump administration’s efforts so far. That target is clearly DEI. DEI and “equity” are really the only terms used in the executive orders (along with “environmental justice,” which shows up with odd frequency) to name their point of attack. As I pointed out earlier, “disparate impact,” and “disparities” never appear; the phrase “affirmative action” appears only once. In all of the denunciation of “illegal discrimination and preferences” there is no suggestion that DEI actually emerged from the Left’s radical interpretation of civil-rights law. And there is no discussion anywhere at all of Title VII.

What DEI and equity are is indeed a bit of a muddle here, and no effort is made to say where these ideas came from. In these documents, both terms seem to refer to one or the other of the two bundles of aims around which my discussion has been organised (group equality and cultural change). In some EOs, DEI clearly means group equality/affirmative action; in some, it means offices, officers, and practices; in yet others, it means bad ideas and cultural indoctrination (“discriminatory equity ideology” in EO 14190). In the one place where a “DEI office” is actually defined—in EO 14185, dealing with the military—its meaning is entirely framed by reference to affirmative action and hiring (“differential treatment” and “special benefits” for minorities). But later in the same document, DEI clearly entails the cultural side of things as well, when the order takes aim at “divisive concepts or gender ideology” and calls for “carefully review[ing] the leadership, curriculum, and instructors” of the service academies to ensure that they do not “teach the theories” associated with divisive concepts.

How or why these different things all qualify as DEI is never spelled out; that problem would disappear were the target instead named with reference to the principles and practices of the anti-discrimination Left. The likely reason that is left unsaid points to the other reason the “civil-rights reform” is not already part of the Trump administration’s messaging—namely, that there would be a short-term price to be paid for taking such a step. It is much easier to attack something vague called DEI (or wokeness) and to trust that public opinion will remain supportive. Turning an anti-DEI campaign into a project of civil-rights reform would require engaging the Left’s takeover of the civil-rights revolution more directly, which very few conservatives have shown any willingness to do (they prefer to deride it as “Marxism” and be done with it).

This is why we must confront the moral hold that the civil-rights revolution still has on American life. Without denying or minimising the great moral power of the fight against discrimination, we must reckon with, and think about, the heedlessness and dangers of moral zealotry. Not for nothing does our liberal constitutional tradition teach us to be wary of “legislating morality.”

Failing to take up the task of civil-rights reform will render what the Trump administration is doing a short-term dramatic moment of upheaval. Republicans must take the long view. There is too much at stake to squander the opportunity these efforts have created.

Three Principles for the Work Ahead

Civil-rights reform is the task, and conservatives’ two slogans in undertaking it ought to be colourblind equality and “1964 originalism,” limited and guided by the wisdom of our liberal-democratic constitutional heritage.

Colourblindness is mainly a stance against affirmative action, but it calls us back to a noble ideal of equal citizenship and equal treatment under the law. Policies that privilege groups are unjust and divisive and must be eliminated—that ought to have been the chief lesson of the civil-rights movement itself. This is already the vision of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, invoked by the Supreme Court for many decades; we now have the opportunity to entrench that position more deeply and to broaden its hold on American life.

As to 1964 originalism (a term coined by Richard Hanania), it is important to be clear that the core commitments of the 1964 Civil Rights Act will remain intact. There was nothing wrong with the basic achievements of the 1964 Act’s efforts, as stated in the text of the law, in both the public and private sectors. Almost nobody wants to bring back racially segregated restaurants or permit openly discriminatory hiring and firing by private companies. And almost nobody wants to roll back other basic achievements of the civil-rights revolution, either: equal opportunity in the workplace for women, equal education for women, gay marriage, age-discrimination protections, and disability-discrimination protections. It seems safe to assume that Trump’s political instincts, if nothing else, would slap down any attempt to move on any of these settled matters.

But 1964 originalism would mean a significant shift from where we are today. When the Left expanded the civil-rights revolution beyond its decent aspirations (with the help of Republicans), they launched American politics on a misadventure that nearly wrecked the country. Crucially, 1964 originalism must be guided by the wisdom of our liberal-democratic constitutional tradition. As I pointed out earlier, liberal principles—especially free speech and due process—have already been doing yeoman service in fighting off the excesses of civil-rights zeal. We could do more to clarify just how far the anti-discrimination revolution went to undermine our liberal heritage. Doing that would usefully remind everyone (including postliberal conservatives) just how precious that heritage is. This is a lesson that a broad civil-rights reform effort would create the occasion to learn and to teach, were we to look back to its principles and ideals in a deliberate way for guidance.

Rethinking the revolution—paring it back to its solid and sensible starting point, and ensuring that its basic achievements will be led and moderated by the central teachings of our liberal-democratic constitutional tradition—in the face of political opposition won’t be easy. But that is the real task before us. Anything less would waste all of what has already been accomplished.

The Fight for Civil-Rights Reform Is Just Beginning

The anti-discrimination Left is not going to go quietly. It will continue to be defended in blue states. It will certainly be defended by the employment-discrimination attorneys’ bar. And it will live on in our universities and in the wide array of social institutions that have already been overtaken by its mindset.

But within the federal government, it has suffered a serious blow. DEI officers resisting removal have little legal basis for doing so and will now be rooted out by the very civil-rights machinery they created. DEI offices will not be permitted to rename themselves. In the short run, the prevailing civil-rights dispensation will not be defended very effectively, as it was in earlier Republican administrations, by career bureaucrats in the Department of Justice and other federal agencies. The Trump purge will, at the very least, diminish the energy of such efforts, as will its strategy of advancing a more conservative (“colourblind”) interpretation of civil-rights law.

Nor will it now be defended from that left-wing bulwark, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). One could reasonably argue that Trump’s removal of two Democratic Commissioners will be overturned in court. But in the meantime (which could be a year or more of lawsuits), the EEOC is decapitated and neutralised as a leadership fortress of the anti-discrimination Left. One current Commission vacancy might permit Trump to name a Republican soon. Even if the two fired Democrats are reinstated, the term of one will expire in July 2026, allowing Trump to name a third Republican Commissioner, putting the EEOC legally in GOP hands for a change. And if none of that works out, the EEOC remains quorum-less, incapable of making policy decisions, and headed by its lone Republican appointee. (If ever there was a case for turning an independent regulatory agency into a regular administrative unit, subject to normal “political” oversight, the EEOC is it—certainly “expertise” has never justified the Left’s near-total domination of this institution. But doing that would require Congressional input.)

Education will be a crucial battleground. Now that the spell has been broken, the powerful hand of the law can be used to reshape this extremely important area of American life. Higher education and public education have long been tightly held territory of the anti-discrimination Left. A “Dear Colleague Letter” issued by Trump’s Department of Education (DOE) on 31 January this year is an important step, committing the government to restoring Betsy DeVos’s important 2020 Title IX reforms, which guarantee that due process and freedom of speech concerns are not tossed aside. Higher education accreditation “diversity” standards must be rewritten by the DOE as well to ensure that they are purged of DEI content and reflect colourblind non-discrimination. Similar measures affecting K-12 should be introduced as well. Teacher education’s long history under the guidance of official multicultural education policy (since the 1970s), critical race theory, and similar ideas should be re-examined.

Taking 1964 originalism seriously will mean that some of the basic building blocks of Title VII employment-discrimination law need to be revisited. Attorney fees for plaintiffs but not for defendants encourages dubious and wasteful lawsuits; the rule must be made fairer to both sides. Damage caps and limits to punitive damages ought to be written into the law. Other basic features of Title VII’s enforcement machinery created a legal godzilla for the anti-discrimination Left that should be rethought. Almost nobody even sees privatised enforcement of anti-discrimination to be a problem. “Hostile environment” harassment remains a wide-ranging and mind-bogglingly expansive concept. It’s easy to see problems in diversity training and corrective firing and the like, but if we are to reform those excesses for the long haul, it will be necessary to rethink the Ellerth-Faragher “preventive and corrective” measures regime. So far as I can see, conservatives are not thinking about any of this.

Trump’s executive orders already indicate that the government understands that the campaign must extend to other borderlands between public and private where the reach of anti-discrimination law has long done its indirect but powerful work. Professional associations that carry official sanctioning power provided by law—the American Bar Association, the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and so on—must be made to show that they do not wield their authority in ways that take sides with the Left’s anti-discrimination extremism. As the EOs likewise remind us, federal funding of medical and other scientific research must be purged of DEI litmus tests. So, too, must the efforts of agencies like the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

There’s still a lot left to do, and if these efforts are to be successful, they will need to be led by people informed by an understanding of the civil-rights regime. Clearly, the people who wrote these orders know a lot, and they are looking ahead. But presumably, they also grasp that others do not see the big picture as clearly as they do. Civil-rights reform will therefore require a campaign of civil-rights civic education as well. What the anti-woke “elites” have already figured out will need to be conveyed effectively to the American people in party-platform planks and so on.

Finally, if Aristotle was right and politics really is architectonic, we have every reason to think that sensible changes to our laws will have powerfully beneficial “downstream effects” on the American public at large.

In the 1940s, social scientists gathered to ponder the question of whether or not anti-discrimination law reaching into the private sector could break the hold of Jim Crow. They thought that it could, and that it would do so on the social and psychological plane. But they—and the authors of the laws that followed in the 1960s—radically underestimated just how far that project could or would go. We ought to be confident, today, that a reasonable and well-informed restriction of the civil-rights revolution’s extreme and radical elements will have a beneficial effect on our social and political order, our way of life, and the citizen-mind.

Given the challenge that the Left’s civil-rights extremism represents to our liberal-democratic constitutional order, ushering in an era of civil-rights reform would be a lasting legacy for Donald Trump that would elevate his presidency to truly historic levels of achievement. Here, indeed, would be true greatness.

The opinions expressed here are not endorsed by any institution with which the author is affiliated.