Art and Culture

The Thunder from Down Under

If Bach was the sound of God whistling while he worked, AC/DC was the sound of God ordering another round in a strip club on Saturday night.

A full audio version of this article is available below the paywall.

Fifty years ago, most citizens of the northern Anglosphere would have assumed Australia’s contribution to world culture began with didgideroos and ended with “Waltzing Matilda.” But that was before they heard the new five-piece rock ‘n’ roll outfit formed in the Sydney suburb of Burwood by two Glasgow-born brothers, Angus and Malcolm Young, who had just hired a third Scottish expatriate a few years their senior, Ronald Belford “Bon” Scott, to be their frontman. For the next five decades, AC/DC would help to transform the international reputation of their adopted homeland with their antipodean take on booze- and sex-soaked rock and roll. If Bach was the sound of God whistling while he worked, AC/DC was the sound of God ordering another round in a strip club on Saturday night.

Like many performers from their era who are still active today, AC/DC’s ongoing commercial viability was secured early in their career. The band released the most recent of their seventeen studio albums in 2020, but their live set-lists are still dominated by tracks drawn from the iconic records they recorded between 1975 and 1981 when they were at the height of their powers. Anthems like “TNT,” “Whole Lotta Rosie,” “Highway to Hell,” and “Dirty Deeds Dirt Cheap” have long been staples of classic rock radio and can still be heard blaring in bars, on movie soundtracks, over sporting events, and out of countless personal listening devices. Their 1980 album Back In Black remains one of the biggest-selling records of the recording era, in company with Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors. Today, lead guitarist Angus Young is the only original member, but the band continues to pack arenas and stadiums. In 2025, they are scheduled to play a list of huge venues in Canada and the US following a round of blockbuster European gigs in 2024.

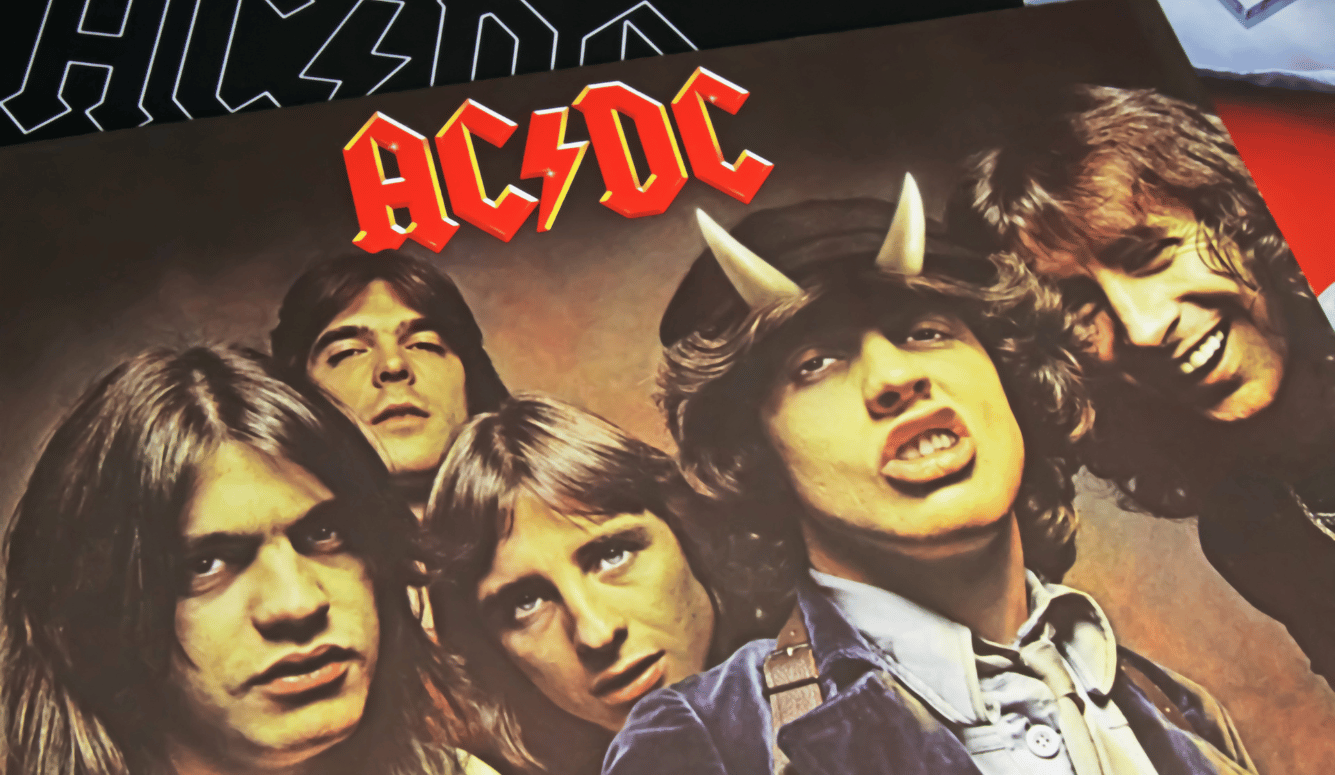

AC/DC’s lightning-bolt logo is one of the most recognisable corporate signatures on the planet, as instantly legible as the Amazon arrow, the Nike swoosh, the McDonald’s arches, the Rolling Stones’ tongue, Led Zeppelin’s fallen angel, and the Beatles’ apple. Memorials to Bon Scott, who died in 1980, now stand in his childhood home of Kirriemuir Scotland, Fremantle in Western Australia where he was raised, and in Melbourne’s AC/DC Lane. For those unable to afford Ticketmaster’s astronomical stadium prices, tribute bands—including all-female iterations like Hell’s Belles and ThundHer Struck—keep the party going on the pub and club circuit. The quintet was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2003. Even people who don’t like hard rock at all probably know something about AC/DC: the image of Angus in his schoolboy outfit with his trusty Gibson SG; the Satanic group portrait on the sleeve of Highway to Hell; and an entire genre of roadhouse raunch and blue-collar boogie that originated in the baking sunlight of New South Wales.

Though guitar-based rock music was a crowded field in the mid-1970s, AC/DC’s visual, aural, and lyrical identity soon set them apart from the competition. Honed in the gruelling outback circuit of their homeland, the band’s live shows consistently delivered a sustained burst of high-energy entertainment. The spectacle of Angus Young’s unstoppable dervish and Bon Scott’s tattooed swagger was complemented by impassive support from Malcolm Young on rhythm guitar, Phil Rudd on drums, and Mark Evans (later replaced by Cliff Williams) on bass. “When you’re onstage you know people have paid to see the high-diving act, so our attitude has always been that these folks are going to see the high-diving act,” Angus explained in 1995. And unlike many established rock ‘n’ roll acts of the day, AC/DC didn’t try to replicate the post-Sgt. Pepper sonic sophistication of exotic instruments, orchestral arrangements, lavish suites of medley, or concept albums. Most of their songs are built around a basic 4/4 time signature, open chords, and single-note licks—a simple formula that Malcolm and Angus refined into a merciless wallop: beginners’ musical techniques executed by seasoned music professionals, at maximum volume.

It was Bon Scott, however, who gave AC/DC its lasting character. A journeyman singer who’d done time in a tough juvenile reformatory and had luckless stints in Australian acts the Valentines and Fraternity, he joined the Youngs with the worldliness of someone who’d already seen the seamy underbelly of life in and out of rock ‘n’ roll. Entrusted to put words to Malcolm and Angus’s progressions, he recounted his own experiences in verse. So here was the daily and nightly reality of young touring performers during a newly emancipated age, frequently cheated financially but reaping as many fringe benefits as they could: “Highway to Hell,” “Rocker,” “Ride On,” “There’s Gonna Be Some Rockin’,” “Let There Be Rock,” and “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll).” Here was the leering chronicle of successful one-night stands and rejections: “Shot Down in Flames,” “Can I Sit Next to You Girl,” “Bad Boy Boogie,” “TNT,” “The Jack,” “Big Balls,” “Girls Got Rhythm,” “Little Lover,” “Soul Stripper,” “Squealer,” “Go Down,” and the true story of Scott’s brief liaison with a plus-sized Tasmanian partner, “Whole Lotta Rosie.” Here were “Jailbreak,” “Down Payment Blues,” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll Singer,” the jaded outlook of a man who knew firsthand the raw deal and rigged game of the modern condition, and here was the denim fatalism of “Sin City”: Rich man, poor man / Beggar man, thief / Ain’t got a hope in hell / That’s my belief.

Scott not only lived the AC/DC ethos, but died by it too. Passed out in a car after a night of heavy drinking, he was found dead on the morning of 19 February 1980 at the age of just 33. Determined to clinch the international success their late vocalist had started to win for them, the grieving Young brothers found it in Scott’s replacement Brian Johnson, who fronted their funeral-party masterpiece Back In Black later that same year. Boasting a monolithic title track, the eventual radio standards of “You Shook Me All Night Long,” “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution,” “Hells Bells,” and the unapologetic “Have a Drink On Me,” Back In Black launched the band into permanent stadium status, which they rode for the next forty years, releasing the occasional new album to promote their latest mega-tour of playing the older material most punters had really come out for.

In time, AC/DC transcended their significance as a particularly tight and hard-working rock ‘n’ roll act to become a show-business powerhouse of sold-out venues and licensed merchandise, as well as a kind of folk tradition. Whereas ordinary men and women had otherwise reached a post-feminist accord on equality in homes, schools, and workplaces, AC/DC’s records and concerts continued to offer a few cathartic hours of what would elsewhere be called toxic masculinity. For a band that made its name catering to the sensibilities of indiscriminately horny larrikins in Australia, Europe, and the Americas—listen to “You Ain’t Got a Hold On Me,” “Love at First Feel,” “Live Wire,” or “Let Me Put My Love into You” for evidence—the sexual politics of AC/DC was nonetheless embraced by generations of co-ed audiences, to whom the larger-than-life depictions of male lust for objectified females were a harmless, and even healthy, pursuit. Imagine thousands of people, many of them couples and many middle-aged, cheering as Angus, Malcolm, Cliff, and Phil thunder over Bon or Brian’s double-entendres about sex and sin, and you get an idea of how AC/DC defined and defied a changed social landscape.

Sometimes this got them into trouble. During the 1980s, a “Satanic Panic” gripped AC/DC’s key market of the United States, where anti-rock religious zealots fretted about Bon Scott’s pentagram necklace and Angus Young’s horns and tail on the cover of the Highway to Hell LP. Preachers and titillated teens whispered that the band’s name was a secret acronym for “Anti-Christ Devil’s Children” or “Anti-Christ, Down with Christ” (they were, in fact, named after an electrical label on the Young family’s sewing machine). Even Back In Black’s ominous opening track “Hells Bells” caused alarm. The Californian serial killer Richard Ramirez left an AC/DC hat at a crime scene, and bragged that their song “Night Prowler” was his inspiration. A seedy 1984 murder case among bored youth on Long Island, New York, saw the accused killer taken into custody wearing an AC/DC jersey illustrated with an image of Angus playing to Satan (the boy hanged himself shortly after). None of this had anything to do with the members of the band. “Just because you call an album Highway to Hell, you get all kinds of grief,” Angus shrugged. “All we’d done is describe what it’s like to be on the road for four years. When you’re sleeping with the lead singer’s socks three inches from your nose, believe me, that’s pretty close to hell.”

Over the long term, though, there was a more secular—and more realistic—rebellion represented by AC/DC’s popularity. Despite big sales of discs and tickets, the quintet had never received much critical respect. Rolling Stone magazine’s review of their 1976 record High Voltage wrote them off as “two guitars, bass and drums all goose-stepping together in mindless three-chord formations.” Both of the Young brothers had noticed early on the disconnect between their growing public appeal and the scepticism of the industry gatekeepers. “When we came to the States in ’77,” Malcolm later remarked, “they told us the timing was wrong for our style of music. It was the time of soul, disco, John Travolta, that type of stuff.” Angus: “What was real strange was that although the media was pushing this really soft music, you’d get amazing numbers of people turning out to hear the harder stuff.” Bon Scott expressed the same sentiment, in language that oddly anticipated the political populism that would emerge decades after his death: “The music press is totally out of touch with what the kids actually want to listen to,” he told a British journalist in 1977. “These kids might be working in a shitty factory all week, or they might be on the dole—come the weekend, they just want to go out and have a good time, get drunk and go wild. We give them the opportunity to do that.”

That sense of speaking for a not-so-silent majority ran deep in AC/DC. Original bassist Mark Evans described his employers to Bon Scott’s biographer Clinton Walker like this: “The Youngs are real Scottish working class, really good strong family, you know, staunch.” Indeed, it was Malcolm and Angus’s older brother George Young who first scored professionally, forming the 1960s group the Easybeats with Dutch immigrant Harry Vanda and notching Australia’s first international pop sensation of the era. The Easybeats’ worldwide hit “Friday On My Mind” was an ebullient single with a pulsating riff that carried a subtle message of proletarian pride. Frontman Stevie Wright sang about working for the rich man through the week until he could spend his bread and lose his head.

George Young and Harry Vanda would go on to manage AC/DC’s homegrown rise, drawing on the work ethic Malcolm had acquired from a teenage job on machines in a Sydney brassiere factory. “It comes from working in the factories, that world,” Malcolm told the now-contrite Rolling Stone in 2008. “You don’t forget it.” Fans always sensed the authentic commitment—and the authentic talent—in AC/DC’s music, and the sense of urgency and drama produced anywhere and any time it comes clanging through the speakers. In 2004, as American infantrymen prepared to move in on the besieged Iraqi stronghold of Fallujah, it was the martial sounds of “Hells Bells” that rang out of the sound system across the desert night.

This year will mark the 51st anniversary of AC/DC’s recording debut in Australia (the single “Can I Sit Next to You Girl”), as Angus Young and Brian Johnson embark on what may be their final tour of North America, where concertgoers will have their ears rung by all the classic odes to hell, rock, sex, high voltage, and other sundry dirty deeds—songs that have become the loud and lewd soundtrack for an eternal adolescent masculinity now embraced by all ages and genders all over the globe. This time around, Angus and Brian will lead a group of newer players filling in for the retired Cliff Williams and Phil Rudd, and the schoolboy’s late big brother. After battling alcoholism, cancer, and finally dementia, Malcolm Young died in 2017. He was remembered at a private ceremony at Sydney’s St. Mary’s Cathedral, where hundreds of spectators gathered outside, and he was laid to rest with the electric guitar Angus carried to his coffin. Bagpipers played “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll),” and the hearse drove away to the strains of “Waltzing Matilda.”