Politics

How the Media Broke the Immigration Debate

What good is a free press if it lacks the courage to ask difficult questions about our most important problems?

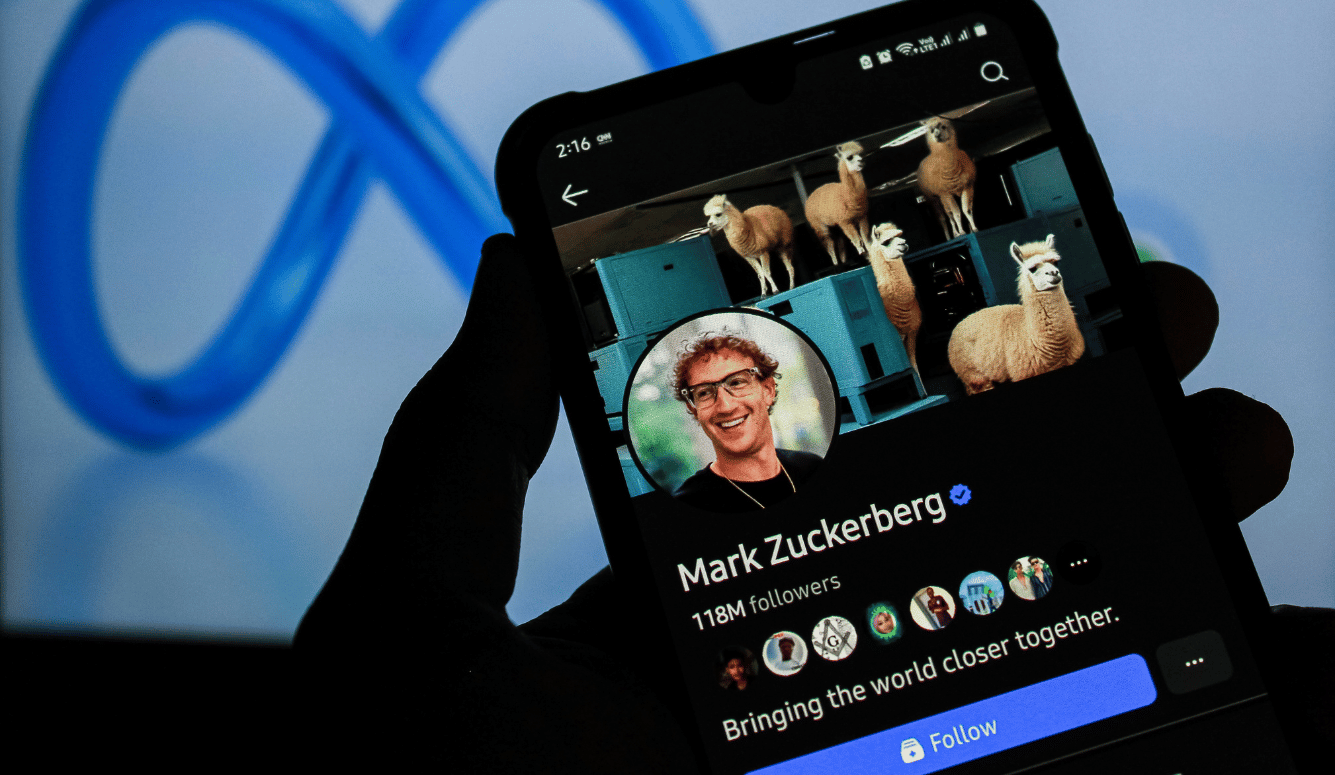

On 7 January, Mark Zuckerberg posted a video message on Instagram, in which he announced that Meta would “get rid of a bunch of restrictions on topics like immigration and gender that are just out of touch with mainstream discourse.” This was an abrupt about-face from the CEO of a company that once employed thousands of content moderators. But who decides what constitutes “mainstream discourse” on controversial topics like immigration? For decades, as Zuckerberg notes, the answer has been the “legacy media.” Over the course of a generation, a small number of progressive editors, journalists, and activists have muddied the language and context of the topic, aggravating one of the country’s most persistent political problems.

“Terms like ‘undocumented’ and ‘unauthorized’ can make a person’s illegal presence in the country appear to be a matter of minor paperwork,” wrote Tom Kent, the Associated Press (AP)’s deputy editor for standards and production in 2012. Kent was responding to a policy proposal to eliminate the adjective “illegal” due to its perceived pejorative nature. Six months later, Kent’s guidance was overruled. The New York Times followed suit within a month. Ten years on, after a historic surge in illegal immigration that overwhelmed federal agencies and major cities, many publishers don’t even mention legal status when discussing immigration. So, how did we get here?

Back in 1986, when Reagan signed “comprehensive immigration reform” into law, the press used “illegal immigrant” and occasionally “undocumented” and continued to do so until the early 2000s. Some used the terms interchangeably, like then-junior senator from Chicago, Barack Obama, who mixed both in his floor statement to Congress on immigration reform in 2006. Two years later, as president, he appointed Sonia Sotomayor, the country’s first Latina justice, to the Supreme Court.