Politics

Memorial Daze

Notions of injury or exclusion are often based on shifting cultural sensitivities and political pressures, rather than on any permanent, universal measure of good and evil.

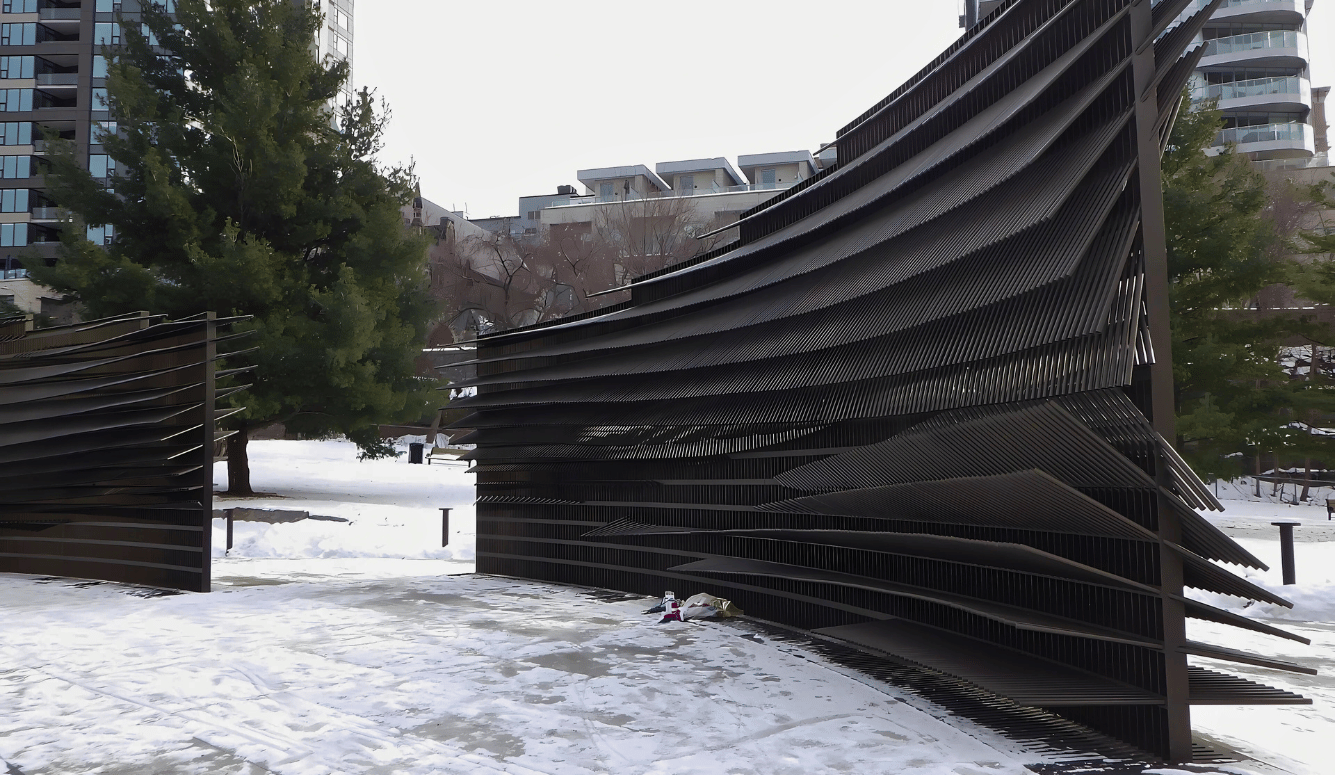

After many delays, Canada’s Memorial to the Victims of Communism was officially opened at Wellington and Bay Streets in the nation’s capital on 12 December 2024. The memorial was originally meant to include a display of names honouring individuals who had fought against Soviet oppression, but it attracted controversy and protests when it emerged that some of the honourees might have fought for the Nazis during the Second World War. “At the time of the unveiling, there will be no names on the monument’s wall,” a spokesman for the Ministry of Canadian Heritage equivocated.

Like many other countries, Canada is home to a number of public buildings, plaques, and shrines marking tragic episodes from history. Of course, war memorials in big cities and small towns have long commemorated soldiers, sailors, and airmen who fought and died in armed conflicts, but a crop of newer structures have arisen to recognise not warriors but victims. There’s a National Holocaust Monument in Ottawa and Holocaust museums in Toronto and Montreal; a Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre in British Columbia remembers the citizens of Japanese origin forcibly relocated during World War II; a Residential School Memorial in Saskatchewan preserves the memory of vulnerable Native children sent to state- or church-run institutions; the Africville National Historic Site in Halifax, Nova Scotia pays tribute to the province’s community of escaped American slaves and their descendants; and a planned “2SLGBTQ+” memorial in Ottawa will mark the career-ending discrimination once faced by Canada’s gay civil servants, military personnel, and others. The imposing Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, Manitoba incorporates all these histories and more under a single, environmentally sustainable roof.

The Memorial to the Victims of Communism was first proposed by an earlier national government in consultation with Tribute to Liberty, a private group that includes Ukrainian, Polish, Korean, Latvian, and Vietnamese Canadian members. They no doubt looked to international examples for inspiration, such as the Victims of Communism Museum in Washington DC, and other cenotaphs in Eastern Europe. More compelling, obviously, was the evidence of communist atrocities that finally became irrefutable upon the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes. These crimes were catalogued in works like 1997’s essay collection The Black Book of Communism and 1986’s Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine by Robert Conquest, which opened with the grim sentence, “[I]n the actions here recorded about twenty human lives were lost for, not every word, but every letter, in this book.”