Capitalism

This Is Not Late-Stage Capitalism

Automation, artificial intelligence, and robotics are set to redefine the relationship between labour, capital, and production.

The idea that we are living in the era of late-stage capitalism has recently gained traction on the Left, particularly among Millennials and Gen Z. The evocative phrase paints a picture of a crumbling economic system, ravaged by mounting social tensions, teetering towards a Marxist revolution.

Karl Marx believed that capitalism was unsustainable and prone to collapse, soon to be replaced by his favoured system of communism, in which goods and services would be distributed by a “dictatorship of the proletariat” on the basis of need, rather than bought and sold in the marketplace. But while capitalism has some tendencies towards inner turbulence, it is quite resilient, having survived in various forms for 177 years since Karl Marx published his treatise The Communist Manifesto advocating and predicting its overthrow.

The term “late-stage capitalism” originally gained prominence in the 1970s, when the Marxist sociologist Ernest Mandel used it to describe a new globalised phase of capitalism marked by the dominance of multinational corporations, financial speculation, and mass consumerism. We have been waiting for this “late-stage” to pass for half a century now—and yet it has not passed.

This is not the first time a Marxist theoretician has labelled a contemporary phase of capitalism as terminal. In 1916, Vladimir Lenin—who was later to become the first Soviet dictator—wrote a treatise entitled Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, in which he identifies imperialism as capitalism’s “highest” and final stage. For Lenin, the rise of imperialism and the concentration of capitalism into monopolies were the harbingers of capitalism’s demise and the dawn of socialism.

One might easily mistake the emergence of nominally communist states like the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China as some kind of pragmatic victory for Marxism. But it was no such thing. These were not places where a collapse of capitalism gave way to communism. What took place was actually the result of opportunistic thuggery, as revolutionaries seized power under the banner of communism only to rule autocratically—or even monarchically, as in contemporary North Korea. And with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reform of Maoist China into a state capitalist autocracy, the world has become more capitalistic, not less.

In fact, since Lenin’s day, capitalism has ascended to newer and higher forms. Lenin was wrong—imperialism was not its highest stage. Western economists developed new ways to balance the dynamism and economic opportunities of capitalism with the human desires for stability and predictability, and the need for jobs for the general population. In the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes published his seminal treatise proposing that governments adopt countercyclical economic policy: spend more heavily to create jobs and build infrastructure when unemployment is higher and the private sector is depressed and cut back when the market is booming and unemployment is already low.

One of the most influential critiques of communism was written by Friedrich Hayek, whose concept of informational efficiency highlighted capitalism’s unique strengths. In his 1945 essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” Hayek argues that the price system in a market economy is an unparalleled mechanism for coordinating dispersed knowledge. In a capitalist economy, prices reflect millions upon millions of individual decisions about supply and demand, and therefore act as signals that guide resource allocation dynamically and efficiently.

There is no such informational network in a centrally-planned communistic system. The knowledge needed to run an economy is not just statistical or aggregate; it is local, dynamic, and often tacit. For example, a small business owner’s understanding of their customers’ preferences or a farmer’s knowledge of local soil conditions cannot be easily centralised or standardised. The market leverages this dispersed knowledge through competition and price adjustments, whereas central planning is inherently rigid and prone to inefficiency.

Aside from a change in emphasis from government spending to monetary policy as the main countercyclical mechanism in the 1970s, capitalism with a few countercyclical adjustments has ruled the day from World War 2 until the present. Yet the Western Marxists never fully went away. Although they have mostly been banished from the field of economics—simply because Marx’s theories about the way the economy works and how capitalism will give way to communism don’t reflect reality—his disciples have continued to beaver away in academia, trying to apply Marxian analysis based on class struggle to a broad variety of topics, including critical theory, sociology, and gender studies.

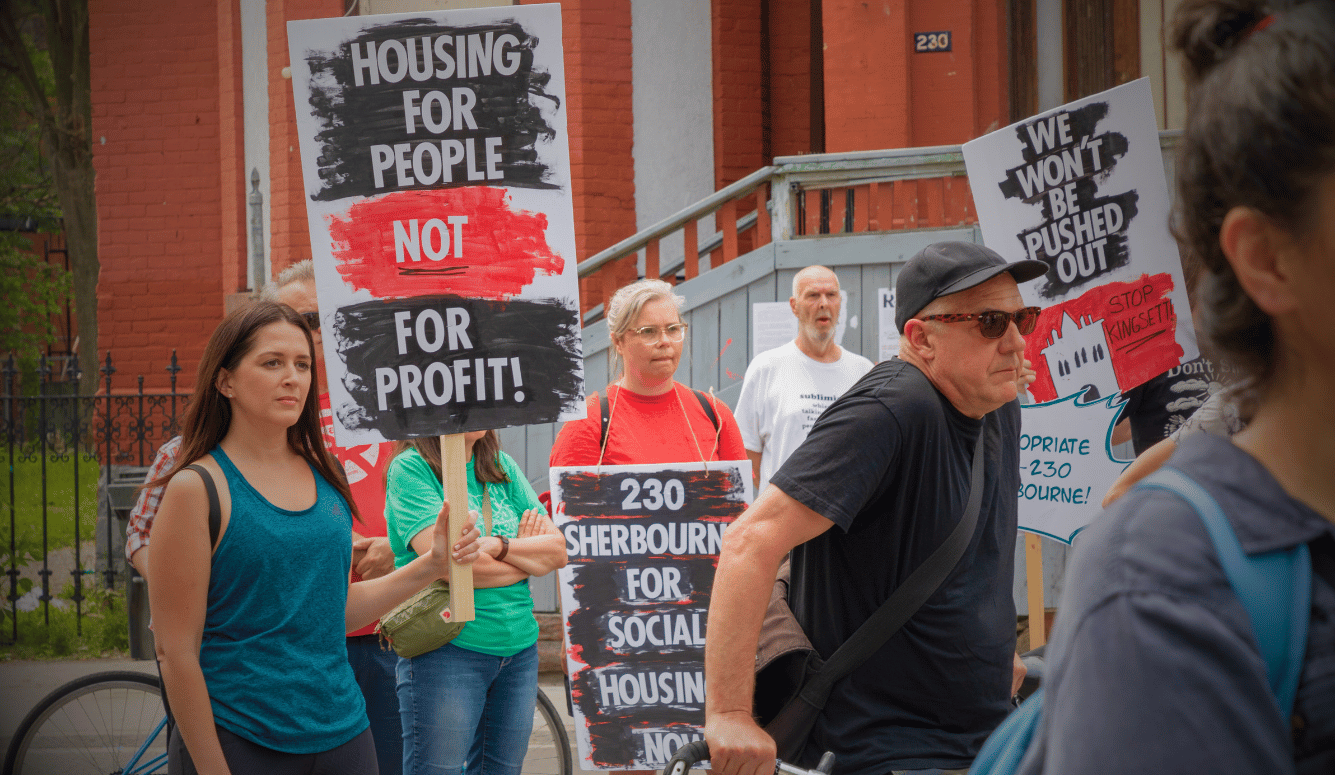

Marxists and their ideological fellow travellers used the 2008 financial crisis as a way to return to prominence by arguing that the crisis was the result of some of the systemic contradictions they had long warned about: unchecked financial speculation, massive inequality, and the fragility of globalised markets. The collapse of major financial institutions, the subsequent bailouts funded by taxpayer money, and the deep recessions that followed provided fertile ground for renewed critiques of capitalism. Occupy Wall Street and similar movements drew heavily on anti-capitalist rhetoric as they highlighted the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few.

But once more, capitalism did not die. Instead, it has demonstrated its remarkable capacity for adaptation and reinvention by responding to crises in ways that, while imperfect, have ensured its continued survival and dominance. The Marxists hope it will be different this time. But they are wrong again. We are not witnessing the end of capitalism, but the early formation of a new phase: autocapitalism, in which automation, artificial intelligence, and robotics are set to redefine the relationship between labour, capital, and production.

Autocapitalism represents a systematic departure from previous versions of capitalism. Historically, capitalism relied on mass human labour as the input that drove production, thus creating a perpetual tension between workers and capitalists. But artificial intelligence and robotisation have changed the equation. By replacing human labour with autonomous machines, capitalists can drastically reduce costs while still increasing output. It is no longer a matter of trying to negotiate labour costs down, or even of outsourcing labour to low-cost regions—it’s about eliminating labour altogether.

This shift has the potential to create enormous economic abundance. Goods and services that once required significant labour inputs to produce may become exponentially cheaper and accessible to far more people than ever before. As Marc Andreessen of Andreesen-Horowitz has argued, automation is in the process of reducing the costs of many economic activities that can be fully automated by factors of 1,000 or more.

Of course, energy constraints will still be an important part of the equation—even if we do seem to be creeping closer and closer towards nuclear fusion. I am not arguing that this new phase of capitalism will be some kind of fully-automated luxury utopia, like the world of Star Trek—although something closer to that may yet emerge decades or centuries further into the future after a lot more technological progress, if we discover a more cost-effective way of producing, storing, and distributing energy.

What I am arguing is that this new world will be even more capitalistic, at least in the sense that far fewer people will be wage labourers, selling their labour to the owners of corporations to survive. Instead, many more of us will have to make our livings as capitalists. An individual’s ability to navigate this new phase of capitalism will increasingly depend on their ability to own and monetise some form of capital—whether it’s intellectual property, shares in automated enterprises, social media, or control over personal technologies like robots or AI that can be directed to engage in productive activities.

Marx’s visions were myopic, and his guidance has led—at best—to brutal forms of autocracy, and at worst to mass starvation and total economic collapse. There is a fundamental flaw at the base of his analysis, which goes far beyond Hayek’s critique of the informational inefficiency of central planning. The root problem is that Marx’s theory does not conceptualise value in a realistic way. Marx believed that capitalism was an unstable system because capitalists were ripping off their labourers by stealing their so-called “surplus value.” Building on the work of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Marx believed that value was generated by labour, and that any profit earned by a capitalist represented a theft from the labourers who created that value via their labour. The resulting conflict of interest between labourers and capitalists is the core tension at the heart of his conception of capitalism. But this is incoherent for a very simple reason: value is subjective. The value of a good or a service is not indicative of some deeper intrinsic truth about that good or service, but simply reflects the needs and wants of its buyer and seller. Capitalists make profits by providing buyers with goods and services that they want at the highest prices those buyers are willing to pay, and by minimising their costs, including their labour costs. In other words, capitalism has not been and will not be overthrown because Marx was wrong about the nature of capitalism, which led him to misidentify the conflict at its heart.

Together, artificial intelligence and robotisation represent a new frontier in production because they allow the inputs of labour to be reduced to almost zero. Artificial intelligence, via a process of iterative trial and error, will allow us not only to automate production but to automate the automation of production. This creates added value without any human labour whatsoever and disproves not only the labour theory of value, but the entire Marxist paradigm. This current phase of capitalism is not “late-stage” at all, and that will only become clearer as technology progresses.