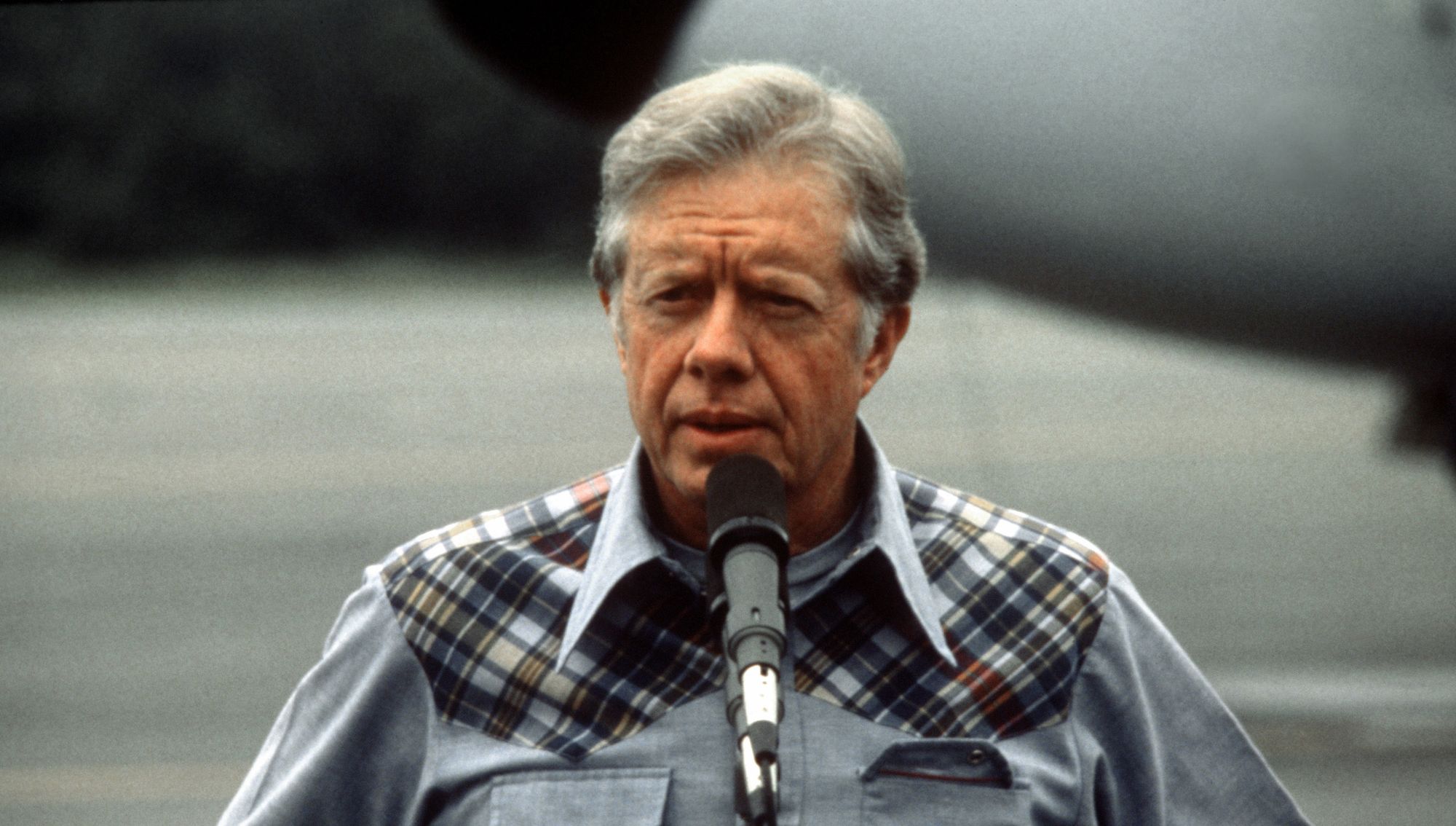

Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter: Human Rights Champion

When we examine the entirety of his long life, we see that Jimmy Carter was among the very best of us.

After almost two years in hospice care, former President Jimmy Carter has died at the age of 100. This makes him the longest-lived former president in US history. The exact medical circumstances are still unclear, but at a century old, it’s fair to assume that his death was the result of natural causes.

As the obituaries, retrospectives, and op-eds about Carter’s life and career roll in, commentators—particularly those on the American left—have been zeroing in on Carter’s time in office, which has cast a shadow over his legacy. A single-term president, Carter was narrowly elected before being defeated in a landslide. His presidency was marred by an economic crisis that he did not create but could not satisfactorily reverse. As a result, he is likely to be remembered primarily as a mediocre leader. But while his failures in office are not in dispute, they don’t tell the full story. When we examine not merely his four years in the White House, but the entirety of his long life, we see that Jimmy Carter was far from mediocre—he was, in fact, among the very best of us.

Born in Plains, Georgia, on 1 October 1924, James Earl Carter Jr. grew up steeped in evangelical Christianity and agricultural life and surrounded by the pervasive poverty of the Depression-era segregated South. After graduating from the US Naval Academy in 1946, Carter was deployed in both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets, where he served with distinction on two battleships and two submarines, as well as with the US Atomic Energy Commission, and ultimately rose to the rank of lieutenant. During Carter’s seven years on active duty, he earned the American Campaign Medal, the China Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. When his father died in 1953, Carter took over the family farm back in Georgia, where he famously worked as a successful peanut farmer.

He entered politics in 1962, with the announcement of his candidacy for the Georgia State Senate. Carter ran as a “new Southerner,” someone who bucked many of the cultural trends of the American South by speaking out in churches and on the campaign trail about the need for racial tolerance, desegregation, and an end to racism. He was the only white man in his community who refused to join a segregationist group called the White Citizen’s Council. Shortly thereafter, he found a sign on his office door that read: “Coons and Carters go together.”