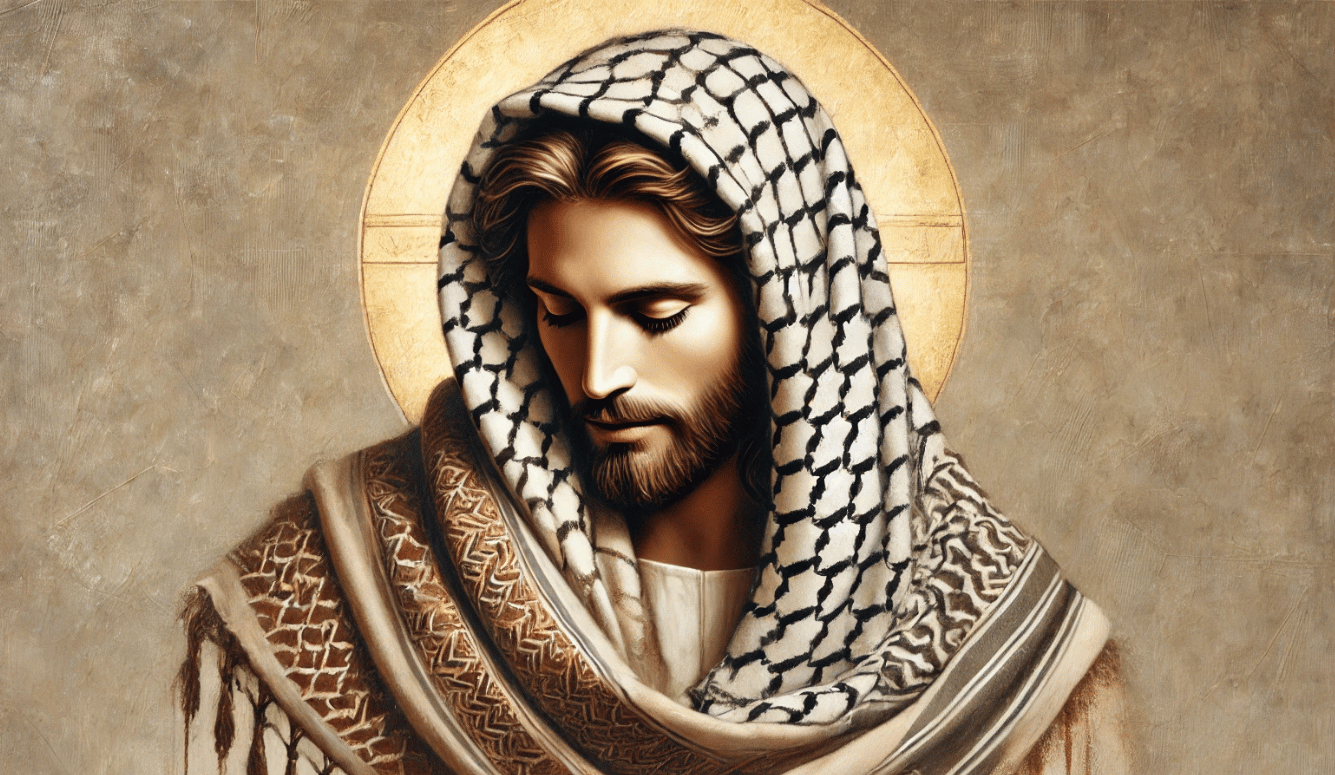

Gaza

Jesus Wasn’t Palestinian

Palestinians’ history, culture, and connection to the land are valid in their own right. We don’t need to appropriate or falsify Jewish history.

A full audio version of this article can be found below the paywall.

Few figures in Middle Eastern or world history are as contested as Jesus of Nazareth. To Christians, Jesus is their Messiah, the Son of God, and God made flesh, the cornerstone of their religion, the world’s largest. During his lifetime, he was a Jewish rabbi living in first-century Roman Judea. The idea that he would become the founder of a new religion might have seemed outlandish to his followers at the time. But that’s exactly what happened. The rapid expansion of Christianity was propelled by the rejection of Jesus as the Messiah by mainstream Judaism; the magnetism of Jesus’s universalist message, which offered salvation to believers regardless of their background or heritage; and the hard work of followers like St. Paul after the crucifixion.

Today, Christians vastly outnumber Jews worldwide. While there are around 15 million Jews, there are over 2 billion Christians, as well as 2 billion Muslims who also consider Jesus a prophet of their religion. This numerical disparity has given rise to some peculiar inter-religious tensions, particularly within the searing cauldron that is the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, where history itself has become a battleground. In recent years—particularly since the advent of the war in Gaza—it’s become common to hear the claim, often chanted by large crowds of demonstrators, that Jesus and his mother Mary were Palestinians, and that the festival of Christmas is a “Palestinian story.”

In trying to analyse such a claim, we first have to look at what it actually means to be Palestinian. While the name “Palestine” is of ancient origin, the modern Palestinian nationality emerged out of the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire. During Ottoman rule (1517–1917), the region that became the British Mandate of Palestine was not officially known as Palestine, nor was it governed as a single polity. Rather, it was fragmented into various administrative districts (sanjaks) within larger provinces (vilayets). Most of the area that includes modern Israel and the Palestinian Territories was part of the Sanjak of Al-Quds, while other parts of the region were incorporated into the Vilayet of Damascus and the Vilayet of Beirut.