Politics

Humanity’s Space Future: Conflict or Cooperation?

The future is unwritten, and a future of space cooperation and peaceful settlement remains possible.

The Apollo 17 mission in 1972 was the sixth and last time that humans set foot on the moon. Now, after a 52-year hiatus, NASA is planning a new generation of lunar missions. These will begin with Artemis II, currently scheduled for the fall of 2025, which will send four astronauts on a ten-day trip around the moon. Missions three to six will put astronauts on the surface and set up pieces of the Lunar Gateway space station. From there, the plan is for future missions to focus on setting up habitable settlements.

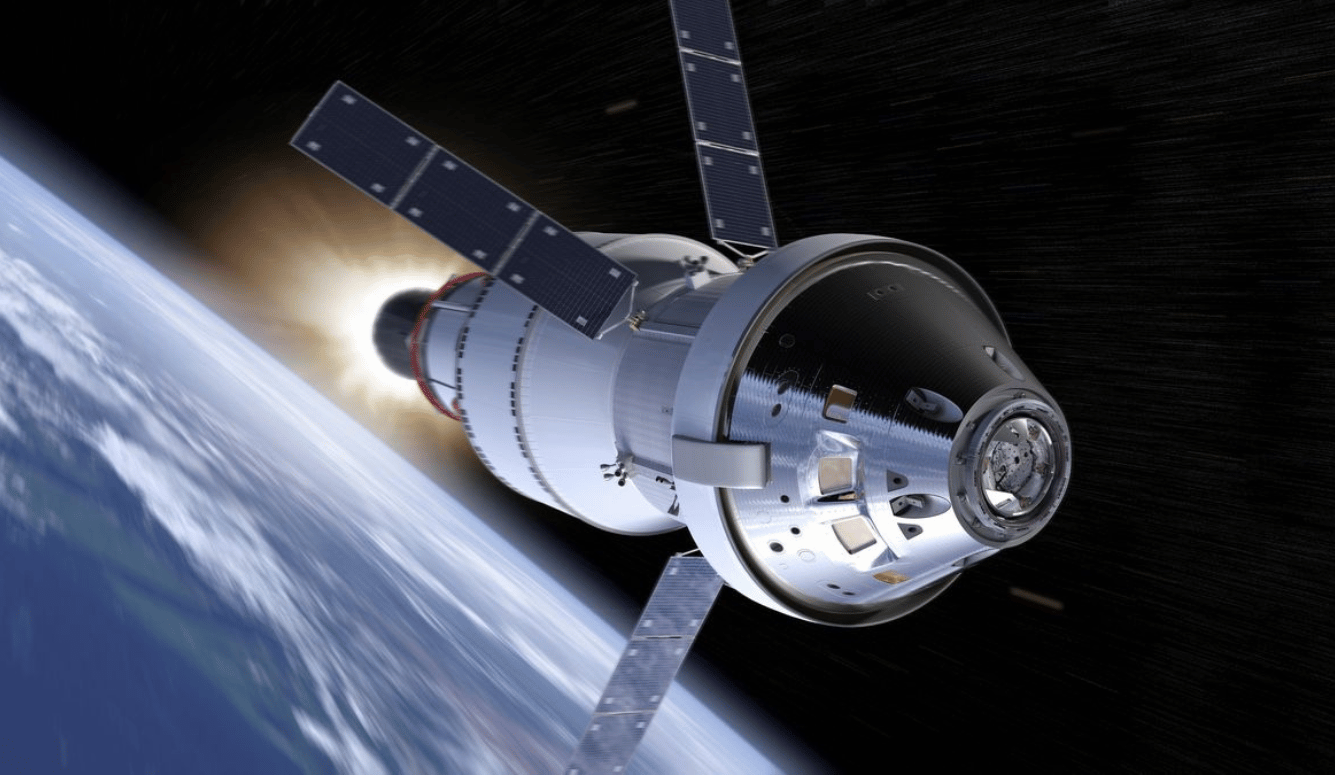

From the beginning, Artemis has been plagued by delays and cost overruns. By 2025, it will have burned through US$93 billion. The first mission, Artemis I, sent the uncrewed Orion spacecraft to orbit the moon, and several issues emerged—the Orion capsule’s heat shield did not break up as the engineers predicted and bolts on the craft experienced “unexpected melting and erosion” according to the mission’s audit. Smart money should probably bet on further delays.

The October issue of Scientific American featured an article by Sarah Scoles titled “Why Is It So Hard to Go Back to the Moon?” During the Apollo years, Scoles explains, NASA was blessed with four percent of the US budget, whereas today it is lucky to get one percent. Space missions also tend to be more global affairs now—the Artemis program is a collaboration involving the European Space Agency, Canada, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates. And we haven’t actually travelled to the moon in decades, and while the basics of rocketry have remained the same, the technology is now more complex.