Politics

Election Reflections

The lessons of the 2024 election are complicated, but they certainly don’t foreclose the possibility of a sane, pro-freedom centre.

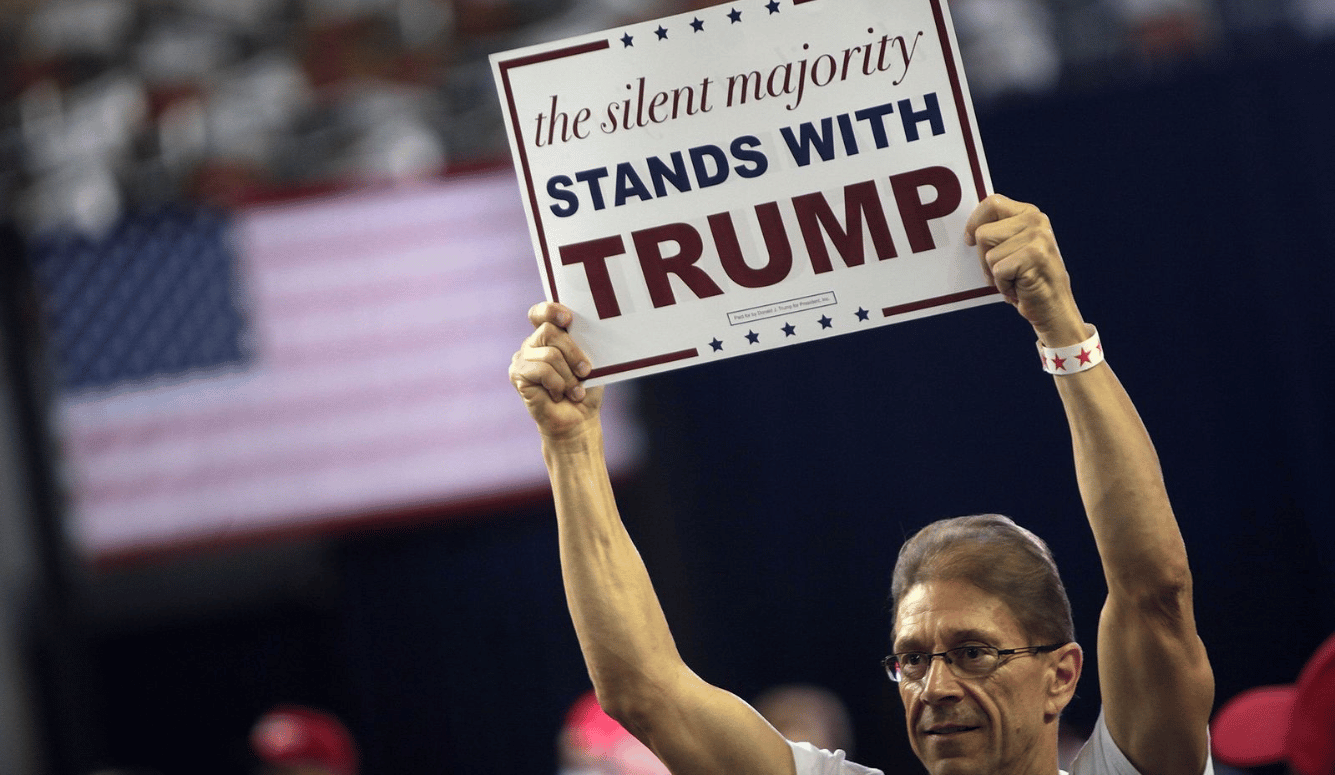

With the US presidential election more than two weeks behind us, the question of why Donald Trump won is still being examined—new polls analyse voting patterns in more detail and new articles discuss the lessons Democrats need to learn from their defeat. As we move past the election and into what promises to be a tumultuous second Trump term, it is still important to review those lessons.

I say this as a Kamala Harris voter with centrist, libertarian/conservative politics who is strongly opposed to the so-called “woke” Left—a position that I believe was compatible with a vote for Harris. Aside from my belief that Trump represents a brand of identity politics and illiberalism at least as toxic as the “woke” kind, the paramount issue for me in 2024 was Trump’s attempt—through spurious lawsuits, the misuse of his office, and finally the instigation of a mob to storm Congress—to disrupt the transfer of power and overturn the results of the 2020 election. I still believe that this alone should have been disqualifying and that his election in itself degrades the American system of governance.

Nevertheless, I strongly disagree with fellow Trump foes, including people I like and respect, whose response has been to pass harsh and sweeping judgment on the Americans who voted for Trump. To say that nearly 77 million voters knowingly endorsed democracy subversion, authoritarianism, and bigotry is both counterproductive and incorrect. People cast their vote for Trump for many reasons, and often with very limited knowledge of his disqualifications. As Adam Serwer notes in The Atlantic, his voters tend to rationalise or ignore—or genuinely not know about—his negative traits and extreme rhetoric.