Memoir

The Baby Gate. A Memoir.

So that’s how a fatherhood ends. A few UPCs, like those you find on packs of toilet tissue, delivered via email.

A full audio version of this article can be found below the paywall.

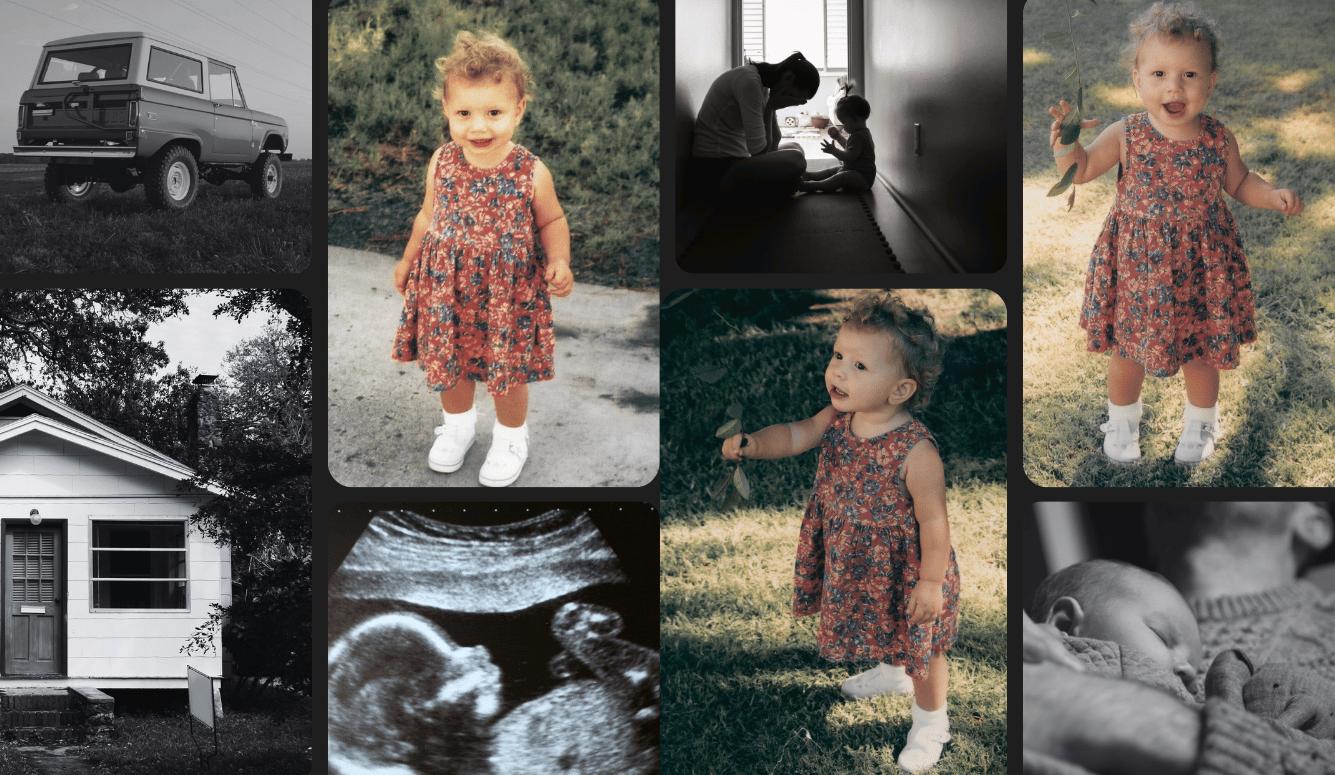

Sophia Corinne Salerno did not cry at her birth—and, at least in the two short years I knew her, seldom cried thereafter. She entered my life with eyes open and unblinking; from the first, she took her breaths with a calm self-possession that would prove invaluable in weathering the drawn-out nightmare of her parents’ uncoupling. It was Sophia’s misfortune to be born into a relationship whose principal players were united in just two things: their love for her and their contempt for one another. On this one anodyne day, however, both of them—my son and Sophia’s mother, Jessica—beamed at each other as I’d never seen them beam before, and would not see them beam again.

Although I had no way of knowing it, the day of Sophia’s birth was a perfect metaphor for the double-edged role the child would come to play in my life: a day of gorgeous platinum sunshine bounding off two-day-old snowdrifts, filthy and unappetising as only aging urban snowdrifts can be. We then lived, all of us, in Indianapolis. The date was February 2, 2000. Groundhog Day. My wife Kathy took to calling Sophia “our little groundhog.” She said it in a soft, singsong voice that somehow wasn’t cloying; we all began referring to Sophia that way, with that same intonation. Even my burly, thuggish son said it that way, merely substituting “my” for “our.” And now, more than two decades later, despite all that has happened—even despite the shattering news that recently blindsided us after years of healing—I still remember Sophia that way. I hear that soft, singsong nickname.

After the baby’s placid demeanour, the other primary topic of conversation was her lack of hair. “Our first baldy!” Kathy exclaimed with a mixture of surprise and delight. Up until then, every baby in the family had been born with a full head of dark curly hair. A baby without hair was a landmark event. Kathy ascribed it to Jessica’s genetic influence. (We hadn’t yet seen the baby pictures of Jessica in which she, too, had a full head of hair.) My son, meanwhile, good-naturedly chided the new mom, “Hey, Jess, you sure she’s mine?”

Jessica laughed—we all laughed—but it became one of those lines that tug at the hairs on the back of your neck when remembered, later, after everything changes.