Nations of Canada

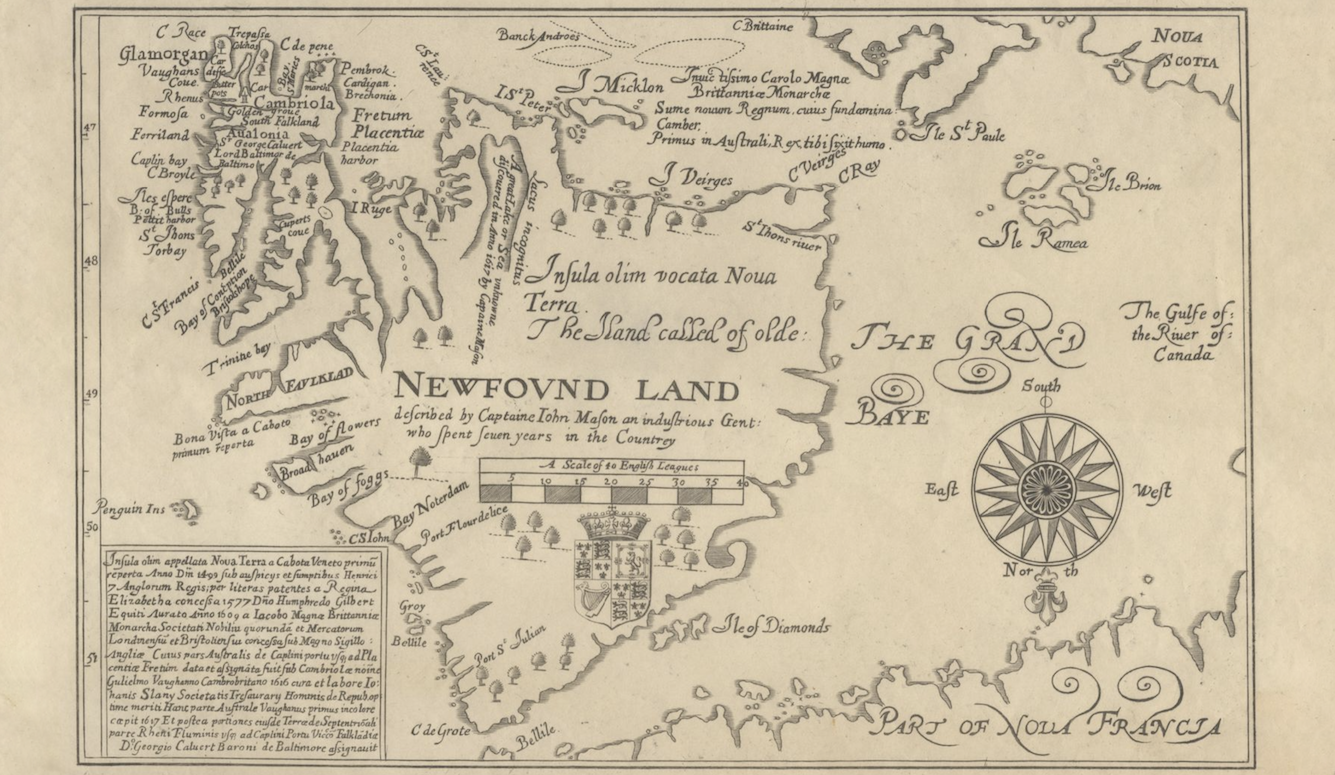

The Dawn of Anglo Canada

In the 23rd instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes the first faltering attempts to bring English and Scottish colonists to Newfoundland in the early seventeenth century.

What follows is the twenty-third instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

As Cardinal Richelieu transformed New France from a trading post on the St. Lawrence into a full-fledged colony in the 1620s, he brought Canada into the sphere of European power politics. Europe’s wars had become global affairs. As a result, the handful of colonists at Quebec were swept up in imperial campaigns far above their pay grade.

It’s important to note, however, that the proclamations made in Paris, London, and Amsterdam during this era often lost something in translation by the time they were communicated to the other side of the Atlantic (a process that took weeks, at best). These policies were interpreted through the prism of local interests, sometimes (as we shall see) in a cynical manner that allowed local actors to prosecute their own parochial grievances or settle old scores.