Art and Culture

Talking Nick Cave Blues

As the Bad Seeds begin touring their acclaimed new album, ‘Wild God,’ Quillette chatted with Australian academic and “Caveologist” Tanya Dalziell about the artist’s music, ideas, and enduring appeal.

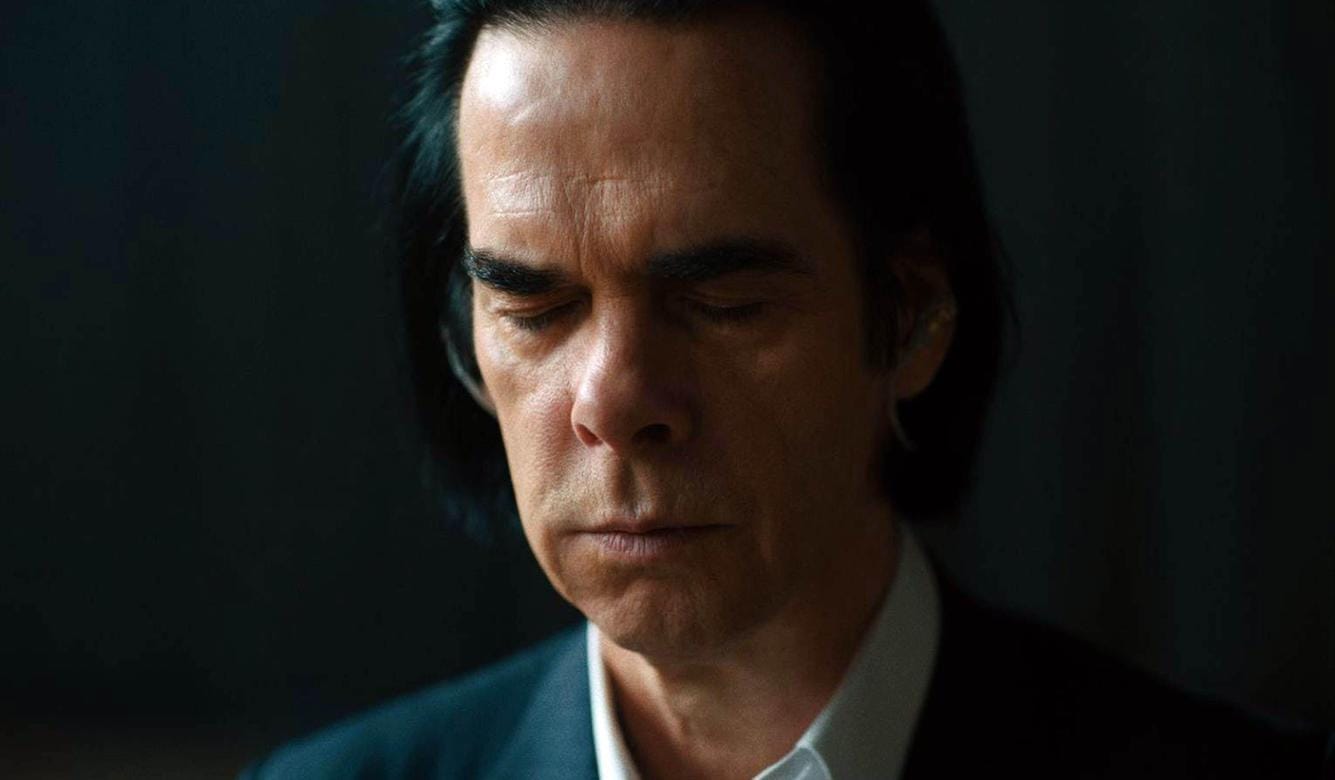

It is probably fitting that the academic I contacted to discuss Nick Cave was Tanya Dalziell, a professor of English and cultural studies at the University of Western Australia, in Perth. For nearly 45 years now, her charcoal-voiced fellow countryman—besuited in black and proffering bouquets of flowers from the pit—has been offering us songs of love and hate. There are rather more of the former on his ecstatic eighteenth studio album, Wild God, which Cave has just begun touring in Europe and the British Isles with the full complement of Bad Seeds. In early 2025, he will cross the Atlantic for a clutch of North America dates.

If the ticket sales match the new album’s swoony notices, the coming shows will be packed. Not only has this graceful record been hailed on its musical merits, it has also been warmly received for its surprising (or so critical wisdom has it) religious airs and overtone. Cave’s charismatic appeal these days has less to do with this-or-that new recording than it does with his broader appeal as an all-points communicator. He’s a novelist and aphorist, developer of glazed ceramics, and an increasingly powerful stage presence.

He is also the creator and curator of the splendid online newsletter called the Red Hand Files, in which he converses with fans directly on an array of subjects. To date, he has fielded some 300 queries—here sexuality or trans rights, there middle-age crises, wars and rumours of wars, and kids who vanish into the night—as kaleidoscopic in their variety as the artist’s responses are nakedly lyrical.

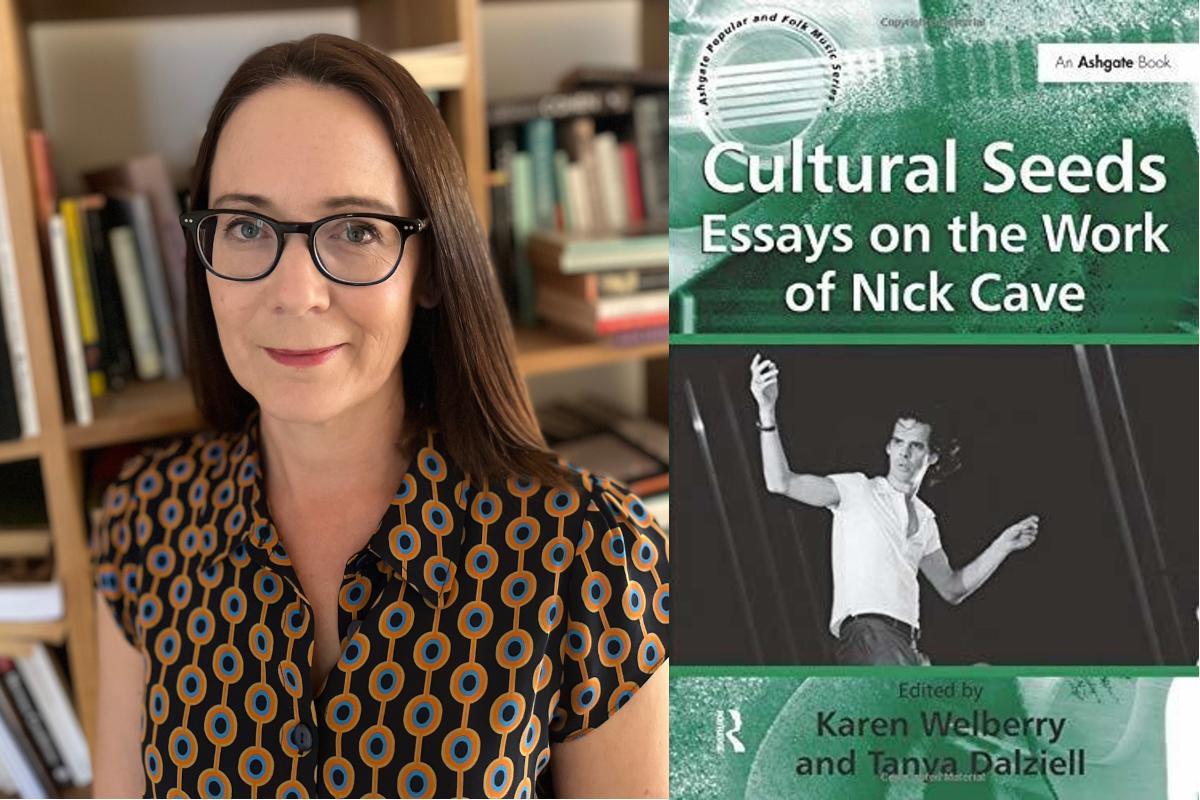

Who better to gauge the star’s current existential pulse than another Australian intellectual in conversation with a South Pacific music writer? A past recipient of her country’s prestigious Prime Minister’s Literary Award, Dalziell also co-edited Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave (Routledge, 2009), making her one of academe’s first fully fledged Caveologists.

Herewith, our conversation for Quillette, lightly edited for clarity...

Quillette: Okay, first things first. Where and why did your academic fascination with Cave begin?

Tanya Dalziell: Hmm. I guess being a scholar evolves into the personal in lots of ways. Clearly, I had been interested in Nick Cave’s work prior to writing about it or thinking about it in a scholarly way. For a long time, I had also been interested in the intersection between music and literature. It seemed like a nice fit, given Cave’s interest in the word and literature and being a novelist as well as a songwriter and a musician. So yeah, I’ve been interested in Cave since I was at high school. It wasn’t a new thing.

Q: As an Australian scholar, did you intend to do something along similar lines with Nick Cave’s music to what your Northern Hemisphere counterparts had already been doing in papers and symposiums on the likes of Bob Dylan, James Brown, and even Bruce Springsteen?

TD: Sure. I think it was less about an Antipodean angle per se than recognising that, along with those others you just mentioned, Cave had a stature and a place. Whilst his writing has had massive press there wasn’t any scholarly work on Cave. Karen Welberry and I thought: Let’s do it! So that was the impetus, the thought that bringing in other points of view could add something to the conversation around Nick Cave.

Q: Which you did with the essay collection you and Welberry co-edited in 2009. How much enthusiasm for his work was there among other scholars at that time?

TD: A lot. I think people were pleased in some ways to write about one of their favourite musicians. But there was an energy around bringing different disciplines together around somebody like Nick Cave who has written, performed, and been part of different aspects of the culture, both popular and underground.

Q: Okay, so you got into Cave while you were a teenager. What was the bridge into his… well, I was going to say music, but as you’ve already suggested, there’s more to it than that, so let’s say art?

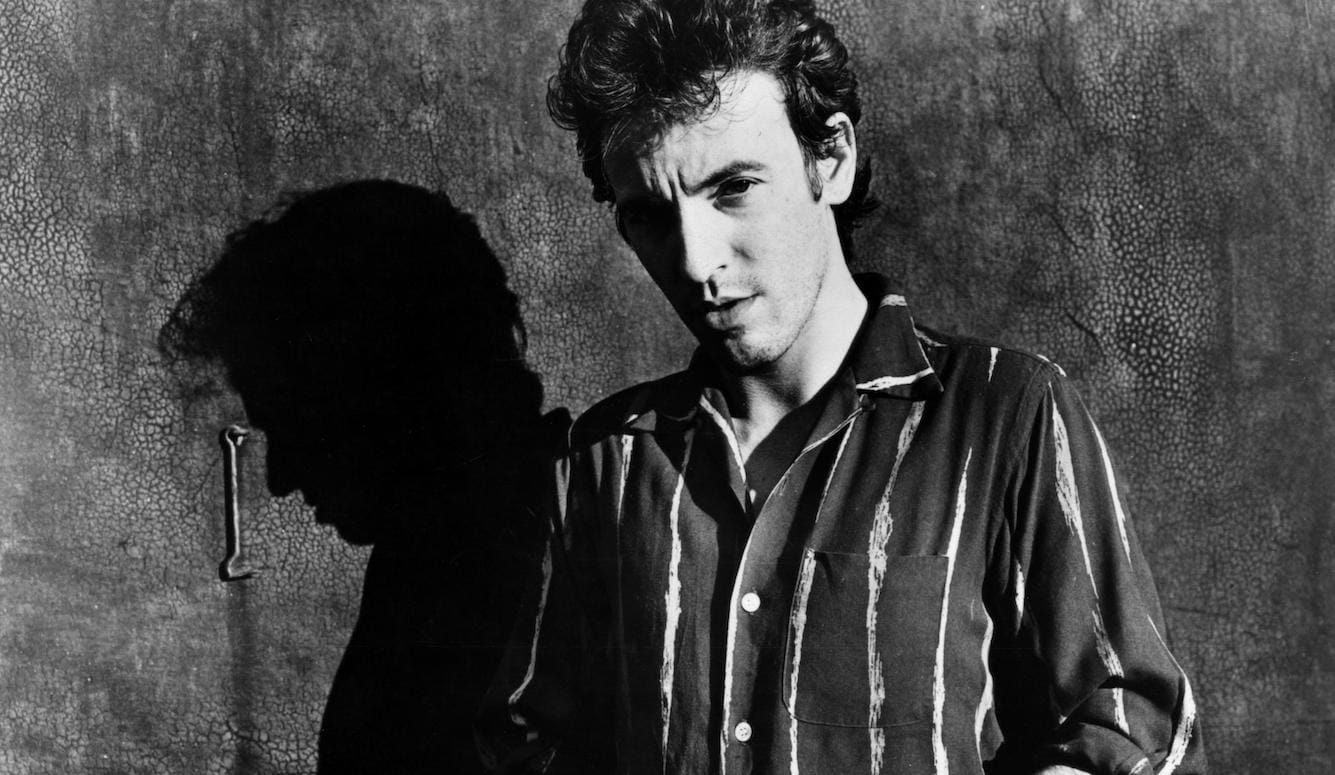

TD: Yeah, I certainly wasn’t aware of him when I was much younger, during the Birthday Party years. But when I started getting into music as a teenager I became interested in alternative or non-mainstream music, and he was one of those figures. But I can’t remember any particular moment where I sought him out. He was just in the ether, as you would know yourself, from the late 1980s when the Bad Seeds were doing something different to what was in the charts at that time. And for me, as someone who even then was interested in literature and words, Cave was fascinating.

Q: Absolutely. I remember first getting into him during the same time as a young journalist who spent a lot of time interviewing musicians. And I just thought he gave the most fabulous interviews, notwithstanding the fact he was junked-out on drugs a lot of the time, and all the rest. But still, he had a command of language in the journalistic form that I responded to. And of course, more recently, we’ve seen his skill in the interview form with Faith, Hope and Carnage, his cosmic conversations with the Observer journalist Seán O’Hagan.

TD: I agree. And it’s continued throughout his career, the Red Hand Files being exemplary of that of course, while noting there have been moments of incomprehension given certain circumstances and on account of what’s been injected in the past. He’s a beautiful, elegant writer, too—more in the short form than the novel form, I would say. Do you know his introduction to the Gospel According to Mark?

Q: Sure. In The Four Gospels, which features Cave, A.N. Wilson, Richard Holloway, and Blake Morrison giving respective drumrolls for Authorised Version translations of the foundational Christian books.

TD: It’s exquisite! And I realise in saying that how vague those judgements are. And also in the Red Hand Files too, in the embrace they invite.

Q: I like your point about him working better in short-form writing. I know this possibly sounds like a pretentious comparison—well, Cave would probably find it pretentious—but I think of someone like Pascal, whose ultra-economical writing in the Pensées you can contrast with his Provincial Letters, which are much lengthier, wordier, and quite unreadable. I’m not saying Cave is unreadable in long-form, but for me he works far better compressed. Since we’re already touching on religion, what do you make of the current tendency to divide his musical output between BC and AD, as it were?

TD: It’s always been there. My goodness, Prayers on Fire is the first Birthday Party album from 1981, right? So, it’s there right at the beginning. Now, as I say, I don’t know Cave and I don’t presume to. But for me, his whole oeuvre is suffused with changing, shifting but nevertheless consistent religious imagery, reaching toward the sacred, battling with some kind of god or some kind of transcendence, whether it be through the vein or through love.

You just have to run your eye over the titles of the records and songs to see that. He’s always been a model of understanding and openness in some ways. If I were him, I’d be pretty annoyed with people thinking that now is the time I’ve discovered religion. I mean, this is someone who wrote a novel titled And the Ass Saw the Angel in 1989. And “Mutiny in Heaven,” on The Birthday Party’s 1983 EP … that’s Milton’s Paradise Lost referencing the Old Testament, right?

Q: Maybe it’s best regarded as religious in a Dostoevskian sort of way?

TD: Totally. It’s a romantic idea of the sublime as well. I don’t see a point in his work where one thinks, “Oh Cave has just found religion.” That would be a misreading of his work, which has been a constant conversation with these ideas, without coming to any conclusion. Which is why he continues—because I don’t think the work is settled.

Q: Yeah, and what about all those King James references, even in the fierce early stuff—all those Solomonic steals from canonical Hebrew texts like Songs of Songs in tracks like “Foi Na Cruz.”

TD: Absolutely. And in something like “Mercy Seat,” that collision of Old and New Testament—you know, the wrathful God and then the hope of some kind of redemption. And goodness is always in there, too. Not that I think he’s always saying the same thing at all. And I’m not talking about growth in that easy kind of linear progression either. But there is this constant tussling and desire for the transcendental—without necessarily finding it—going on, too. So no, there’s not really a linear journey here from the “depths” of the Birthday Party to the so-called joyfulness of Wild God.

Q: Maybe that uncertainty has saved him from becoming one of those repent/believe Christian rock guys, suffused as they often are with absolute certainty about everything. In one of his “in conversation” shows that I attended in 2019, he was saying something about how he can’t really be thought of as a person of faith because he has so much doubt. But of course, faith and doubt are dialectical. All the great religious thinkers have been doubters. In the spirit of John Donne: “Doubt wisely.”

TD: In the Red Hand Files someone asked him if he’d found some kind of truth, or truth-in-progress. So no, he doesn’t have answers to tell us about, and because of that, his art gets away from the whole proselytising thing. There’s a humility there. Attached to the profane, too.

Q: The new album: what’s your first take?

TD: One of the things I admire about him is how his music continues to change sonically and lyrically. So, I know some fans—if that’s the right word—might hope he could still be doing the same thing now that he was doing in 1988. Which he isn’t. Look at the lyrical and musical and theological shifts since then.

I’ve read lots of reviews that call Wild God life-affirming, which isn’t inaccurate but makes me hesitate. You know, “Here’s the Dark Prince who has suffered terribly, experienced loss, and now he’s come out the other end redeemed.” I don’t know. Sonically, yes, it’s an interesting move in his work away from the pared-back trilogy that preceded it. I’m not a music critic, but just from a layperson’s perspective, I would say bringing the Bad Seeds back in was an interesting move. And lyrically, yes, there’s newness there, an attending to life. But I still resist that narrative. What are your thoughts, David?

Q: Well, first of all, just listening to you brings to mind something Cave said to the Guardian some years ago: “The idea that we live life in a straight line, like a story, seems to me to be increasingly absurd and, more than anything, a kind of intellectual convenience.”

TD: Yeah.

Q: So, let’s park the idea of Wild God as some kind of linear progression, and think instead about his work ethic. I know he has always militated against the word inspiration, preferring to see himself as someone who simply turns up at an office others might call a studio and relies on sweat to get by artistically.

TD: Okay, so he puts his suit on and goes to his desk and works…

Q: Well, yeah. That’s how one of his bandmates put it to someone I know when they were touring New Zealand in 2017. It’s all work ethic with Cave, he said, all about the harder one works the more “inspired” one sounds. I’m being a little long-winded here, because I’m shuffling around to the point that, in my opinion, so much of the new record does sound inspired. The surging title track especially. But also tracks like the existentially operatic “Cinnamon Horses” and the limpid “Conversion.”

TD: Yeah—again, saying this as a layperson—as an artist, as someone who is living with his work and having different life experiences, as someone who listens to different music—and all the things that make up your life—he’s not going to be playing “Deanna” all these years later. I do appreciate, in my old teenage kind of way, the fact he’s still experimenting, trying new stuff out musically and lyrically. The first time I heard one of the tracks on Wild God I wondered where the album was going to go. But listening to it as a whole—as an album rather than a TikTok grab—I started to think there was something quite remarkable there.

Q: Another aspect I appreciate anew about the record is the multitalented Warren Ellis—his production smarts, his instrumentalism, and the uncanny way he rides the high notes as a counterpoint vocalist. Not taking anything away from the other Bad Seeds—or from former collaborators like Mick Harvey.

TD: I’m a big fan of Warren Ellis, so you’re not going to get any argument from me. The benefits of Ellis’s full-time injection into Cave’s artistic life are very notable. Again, though, I also appreciate Mick Harvey and all the Bad Seeds, and like you, I wouldn’t in any way devalue their contribution, which is enormous. But the objective listener would have to be aware of Warren Ellis’s impact.

Q: It’s like Cale and Reed, Bernie Taupin and Elton John, Bowie and Mick Ronson, … so much enduring music comes out of partnerships.

TD: Yeah, but unlike Cale and Reed, Cave and Ellis actually get on. [laughs]

Q: How do you think this record stacks up against the other seventeen albums? I know we shouldn’t really rank these things, but I’m a journalist and you’re an academic, so we love rankings, right? Where would you put it?

TD: David, that is such an unfair question, and such an unfair image of academics. I don’t like rankings. And that is such a tricky question for lots of reasons. Some of these albums arrive in your life at important times. It’s just so hard to rank them. I mean, Tender Prey is really a wonderful, amazing record from 1988, and “Mercy Seat” is an extraordinary moment. But, you know, I really like the Grinderman records as well.

Q: I think if I were sentenced to a year on Sumatra and could take only one LP, the one I would choose might be The Good Son.

TD: Why?

Q: Well, I heard it at the right age, it was the first effort that really connected me with his music—and, you know, the first cut is the deepest, and all that. I say this knowing that one shouldn’t remain wedded to “formative” albums.

TD: But what else can you do?

Q: Well, you can put away childish things. I wrote a piece recently on rock critics, and one of the things that repeatedly struck me was how so many people who write about music sometimes aren’t writing about music at all. They’re writing about themselves. They’re writing about what they were doing in their late teens and early twenties, which invariably gets cast as some kind of lost golden age in music. And possibly I’ve just done precisely that in naming The Good Son. As an adult, as a parent, too, I would say the Cave album that puts me under the table is Skeleton Tree. And then rounding out the top three might be Wild God.

TD: I really like Henry’s Dream.

Q: Wow, that’s heterodox.

TD: I know. And I like the B-sides collections, too.

Q: Do you ever think Cave is spreading himself too thin? I don’t ask that because I believe it, but it also seems apparent that he has become the music world’s equivalent of Yotam Ottolenghi, a kind of one-man production house—whether it be the shows and music, the books, the exhibitions, and so forth.

TD: I love Ottolenghi, so that’s no bad thing for me. Why not be artistic in lots of ways, bringing lovely things into the world?

Q: I agree, but how does one person do all that?

TD: Work ethic, I guess. He probably doesn’t have to vacuum his house, so that frees up time.

Q: What did you think when Cave went to Israel in 2017, over the objections of the Roger Waters crowd? I well remember the fire and noise at the time, but I was also in Jerusalem the day tickets went on sale and I remember the tidal wave of local affection there for his decision to tour.

TD: He had a position that he took. I don’t think it was about… well, in the media, he’s talking about how in his older age he’s becoming small-c conservative. I’ve been thinking really hard about that. I’m not sure I would say that. I think his response to the call to boycott Israel doesn’t preclude his understanding or compassion for what’s going on in the world around that issue. And that points to another small-c, and that’s complexity, which I hope isn’t giving him a false out on this issue. (Then again, who am I to say?)

That decision to tour Israel didn’t seem based not on an apoliticism or conservatism but recognising complexity, that there are many people in Israel who would contest their government’s stance as well as many who would support it. It’s like when he’s talking about so-called political correctness. I think he sees the conservatism that’s latent in that, and he wants to rail against what you were talking about earlier—those certainties. I mean, yes, it’s important to stand up for things but perhaps it’s important not to be dogmatic or blanket about it.

Q: Israel brings to mind the subject we first corresponded on: Leonard Cohen and the engrossing book you co-authored about his time on the island of Hydra, which of course is where he also decided to go to Israel in 1973 and support the Jewish state during the Yom Kippur war. At this point in Cave’s career, should we start likening him to a late-career Cohen?

TD: I think we both recognise that Cohen’s late-career surge was for different reasons, which had to do with getting fleeced by a manager. Obviously, Cohen and late-career Presley are artists Cave has his eye on. Do I see him as being in his late career? I don’t know. It’s not like there’s been a lull or a gap. Yes, his life is unfolding, he’s getting older, but late-period? I think he’s in a next-album period. Will we see him still on stage like Cohen when he’s 80? It will be interesting to see.

Q: Yeah, performing “Do You Love Me?” for the 20 billionth time.

TD: Well, Cohen had a particular audience to play to, and he was digging out the old hits. I don’t see Cave as wanting or having to do that. He continues to be curious, whereas Cohen was almost forced to repeat. Cave doesn’t. He wants to connect with his audience, but for him part of that connection remains doing something different, surprising, and exploring.