Europe

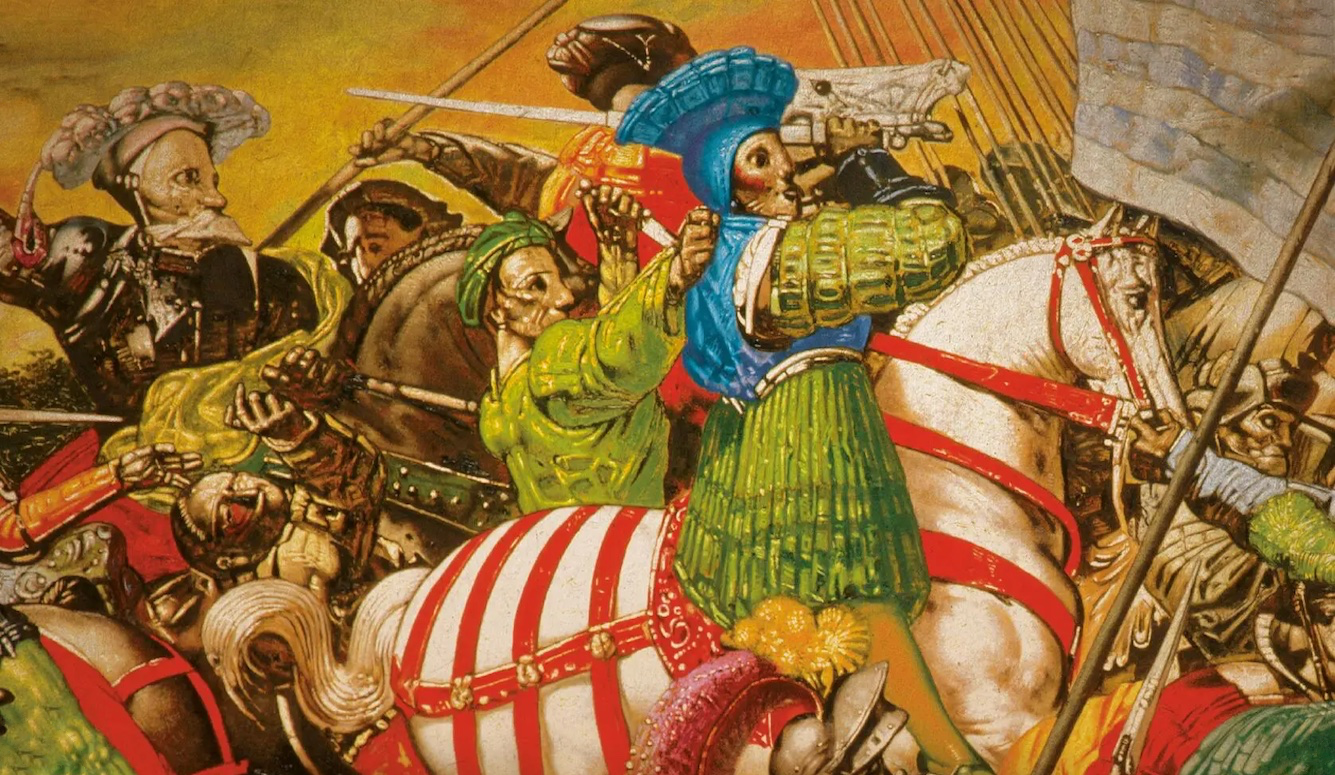

When Germany Waged War on Itself

In a forthcoming book, Lyndal Roper argues that the German Peasants’ War of 1524–25 was a missed opportunity to enshrine a Christian theology centred on equality and brotherhood.

A review of Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper, 544 pages, Basic Books (forthcoming 11 February 2025).

None of the European revolutions that convulsed Europe during the early modern period were tidy affairs. The English Revolution wasn’t just a violent political contest between Royalists and Roundheads, but also an intertwined religious and territorial struggle that drew in warring factions in Ireland and Scotland. The history of the French Revolution, likewise, can’t be neatly separated from the generations-long geopolitical struggle between France and Austria. Later on, the Revolutions of 1848—sometimes referred to as the “springtime of the peoples”—took such variegated forms throughout the continent as to defy any kind of general description, laying a path toward independence for some groups while leading to an enduring authoritarian crackdown against others.

But even by this historical standard, the German Peasants’ War of 1524–25 is difficult to summarise neatly—which perhaps explains why the 500th anniversary of its commencement passed (largely) unnoticed last month. This was a brief and inglorious conflict that left Germans with few heroes to be celebrated in song and stone. Most of the peasants who took part in the fighting likely didn’t see their struggle as a “war” at all, in fact, but rather had taken up arms in response to local grievances relating to lordly (and monastic) abuses of their traditional powers.

In her forthcoming book, Summer of Fire and Blood, Australian-born Oxford University professor Lyndal Roper does an admirable job of describing the war’s origins, protagonists, and major battles. But casual readers may find it tough going, as the complex narrative requires the author to bounce from region to region as she describes the unique circumstances that caused this or that village to join the rebellion. In one area, the casus belli was hatred of a powerful cleric who’d impregnated the mayor’s daughter. In another, hungry locals had been barred from catching fish in a well-stocked pond. In the southern German town of Stühlingen, the countess had enraged her serfs by ordering them to collect snail shells, which her friends at court liked to use as spindles for their sewing thread.