I.

In the department of non-news, the recent revelation that Bruce Springsteen has moved from E Street to Easy Street and joined the billionaire ranks of Taylor Swift, Rihanna, and Paul McCartney deserves a tick. Yes, the working-class hero from New Jersey may now have the disposable cash to buy a highway fit for broken heroes, but his reviews have long been worth a billion bucks as well. This year marks the anniversary of the first and most influential of those notices. It’s the one that would “refocus and alter the course of my life,” as Springsteen later remarked. It also, at least for a short period, refocused and altered the art of rock criticism.

A half-century has now passed since the unexpectedly important night when the then-relatively obscure artist took the stage for a couple of sets at the Harvard Square Theatre in Cambridge, across the river from downtown Boston. Improbable as it might sound in 2024, Springsteen’s following at the time consisted largely of students from a smattering of elite academic institutions. While some fans today are prepared to shell out thousands of dollars for premium seating at a Springsteen show in London, his promoters back in 1974 couldn’t fill a 1,170-seat venue even when they were virtually giving away tickets at $8 a pop.

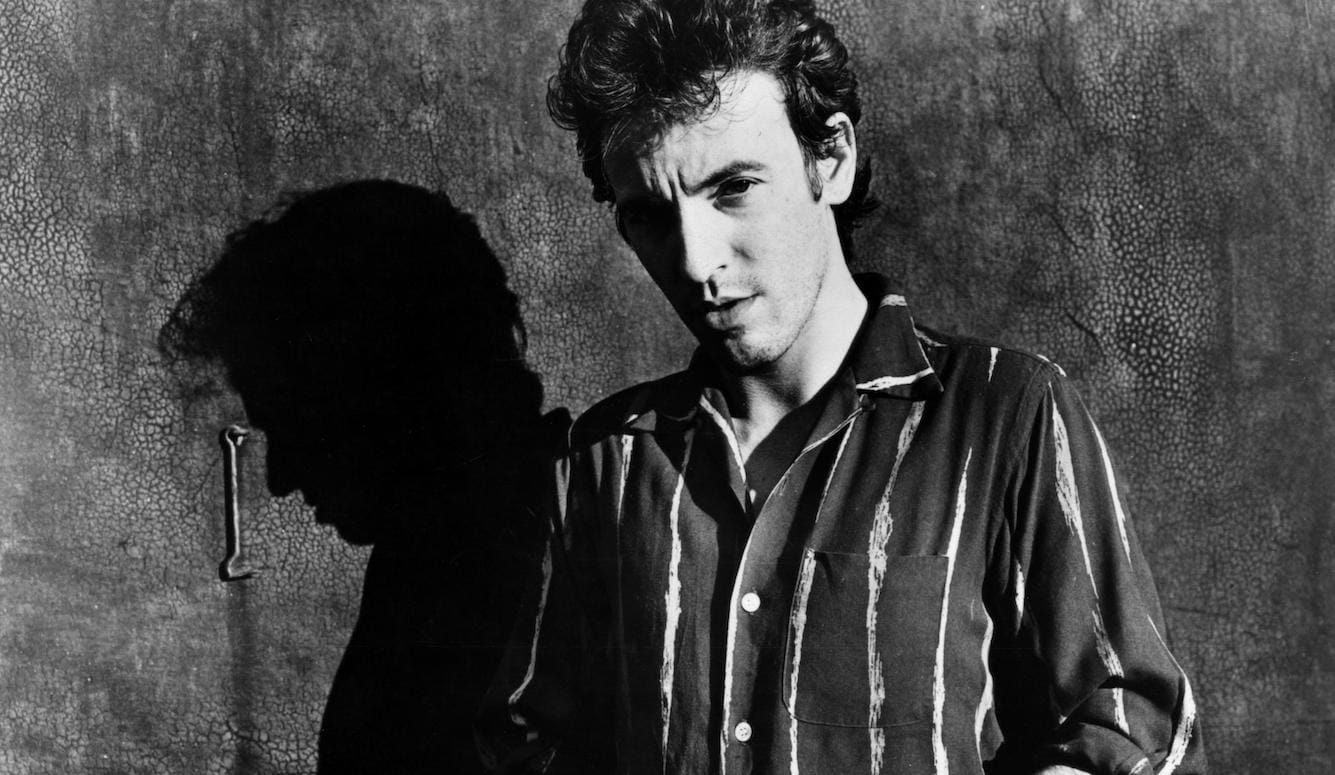

Yes, the lean 24-year-old with the bosky beard had already been discovered by the legendary talent scout John Hammond, and that had to count for something. But Springsteen’s first brace of albums the previous year—the first of which packaged him as the new Bob Dylan, and the second as the next Van Morrison—hadn’t sold terribly well. At Columbia Records, people were openly wondering if anything other than cult status lay ahead of this glorified gutter rat from coastal New Jersey with his mock-tragic songs about girls and cars.

The lack of popular acclaim was reflected in the evening’s billing. Springsteen and his group (who would be identified as the E Street Band for the first time that night) were relegated down the ticket headlined by the red-headed blues rocker Bonnie Raitt. Yet neither act was destined to be the ultimate star that night. That distinction belonged to a dark-eyed record-store clerk turned fledgling record producer and writer, Jon Landau, whose work was about to transform Springsteen’s career and his own. Out in the bouncing crowd that Thursday night, the transplanted New Yorker sat, mouth agape as he mentally drafted lines for his next column in the local alternative music sheet, Real Paper.

On the face of it, the sleepy-lidded piece he produced under the headline “Growing Young with Rock and Roll” hardly seemed destined for the rock pantheon. Clacked out in the small hours of his own 27th birthday, it began with sixteen long paragraphs of nostalgic throat-clearing, during which Landau reminisced about a litany of departed performers and recording artists whose music had once touched his life. Except one:

Tonight, there is someone I can write of the way I used to write, without reservations of any kind. On a night when I needed to feel young, he made me feel like I was hearing music for the very first time. When his two-hour set ended I could only think, can anyone really be this good, can anyone say this much to me, can rock and roll speak with this kind of power and glory?

Landau hardly referred to any of the compositions his new hero had performed at the gig from his recently released LP The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. No mention either of Springsteen’s great covers—notably a creamy version of “I Sold My Heart to the Junkman,” a high and lonesome doo-wop standard originally recorded by the Silhouettes. Nor a word about the songs’ complicated structures, their harmonies, or their dense arrangements. Even the descriptions of Springsteen’s performance (“dressed like a reject from Sha Na Na”) were not especially edifying.

What the piece did offer, however, was a couple of killer lines that changed not only the way people thought about the artist but the style in which a generation of critics wrote about popular music: “I saw my rock ’n’ roll past flash before my eyes,” Landau gasped (and here one could almost hear the band momentarily pause to allow Landau’s new hero to bellow “hun-two-th’ee-foh” ahead of the clincher): “I saw something else: I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.”

And the rest, as they say, is hysteria...

II.

Rock and roll future, eh? Brilliant stuff. And maybe somewhat preposterous, too, the idea of this young Brandeis University graduate casting his weathered gaze back at the moon-burnt nights of a long-lost past. And yet—wasn’t Springsteen essentially trafficking in the same sort of mythology? All those scrappy tunes about cars with ludicrously huge fins, porches with screen doors, and pretty girls (often named Mary) climbing into his passenger seat? This stardust music made an elderly 24-year-old feel the way he used to.

No matter. Landau had shown himself to be an inspired musical phrase-maker. And with his “I have seen rock and roll’s future” line, he found an advertising strap-line for the ages. Soon enough it was everywhere, and the editors at Time and Newsweek were splashing Springsteen on their respective covers in the same week. By this time, the critic who started the commotion had already jumped the fence to become the co-producer of Springsteen’s monumental Born to Run album in 1975. He remained to work on everything Springsteen waxed up until 1992’s simultaneously released long-players, Human Touch and Lucky Town.

It had been Landau’s decision to switch studios halfway through recording Born to Run to help obtain the Spectorian rinse that Springsteen needed for his nine songs. And it was Landau who helped resolve the issue of the thin drum sound that had diminished the sonic heft of the previous two albums. Diehard fans may disagree over the merits of Born to Run, but there’s no arguing about what its appearance and the critic who made it possible meant for aspiring rock reviewers. Suddenly (or so it seemed), following the Landau style became a viable career path. And there were many takers. Not just in the American epicentre, but over in the UK and Ireland, too, and even in Australia and New Zealand.

Landau had working connections with most of the stateside outlets that mattered. In addition to the Real Paper, these included Crawdaddy, the mimeographed publication launched in Boston by a teenaged Paul Nelson, and Detroit’s hipper-than-thou mag Creem. At Rolling Stone, established eight years earlier in San Francisco, Landau had been one of the earliest hires as an actual rock critic, working alongside the magazine’s first reviews editor, Greil Marcus. “God, it was so exciting to read people grappling with this stuff that you cared about in a kind of language that you never imagined would be applied to something like that,” Marcus later marvelled.

Alongside Landau, Marcus, and Nelson, some of the top stateside practitioners included Lenny Kaye, the Australian expat Lillian Roxon, Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner, and the two Richards (Goldstein and Meltzer). A sexual outrider among all the young dudes was Ellen Willis, who had rather more to say about Springsteen than the curiously silent females who populated his music. Writing in the Village Voice, Willis criticised his melodies as “shapeless” and some of his earliest work as entirely “unlistenable,” but relented a bit in her conclusion: “I’m not ready yet to endorse Jon Landau’s rash proclamation,” she wrote, “but in the present he sure provides a good night out.”

As well as being guys, most of these new reviewers also happened to be Jewish. Indeed, if one thinks of the cultural roots of the other songwriters they tended to interrogate most ferociously (Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Donald Fagen, Randy Newman, Lou Reed, Paul Simon, and all the rest) it’s tempting to see the exercise in Talmudic terms. Almost, but not quite. Despite employing a young Israeli recently out of the IDF for the 23-part violin intro to the song “Jungleland”—and promptly falling in love with her, by many accounts—the Irish-Italian songwriter belonged to another important American religious story. “In Catholicism,” Springsteen later wrote in his memoir, Born to Run, “there existed the poetry, the danger and darkness that reflected my imagination and my inner self. I found a land of great and harsh beauty, of fantastic stories, of unimaginable punishment and infinite reward.”

The greatest rock critic of the era wasn’t Jewish, either. Lester Bangs was a displaced Californian dishwasher who had been raised a Jehovah’s Witness before making a name for himself in Detroit as editor of the supremely irreverent Creem. As well as producing (along with his stablemate, Nick Tosches) a kind of primal journalism based on the sound of rock music, Bangs had a memorable knack for never quite letting the reader know if he even liked a particular artist. For instance, when he hailed Springsteen for having become “a household name,” he added with a cough, if one happened to live in a household with “a literate rock critic who likes narrative songwriters.”

Possibly Bangs was also thinking of Dave Marsh, a cultural conservative from the American Midwest with whom he worked at Creem and once came to physical blows, and who is widely credited with coining the term “punk rock.” Mostly, though, the now-retired critic is best remembered for outflanking Landau when it came to his raging passion for Springsteen, having married the artist’s co-manager Barbara Carr, and eventually crushing out no fewer than four biographies of the man from Asbury Park, NJ.

III.

I know a bit about this. The first of Marsh’s deferential works, Born to Run: The Bruce Springsteen Story, produced when the author was a still-tender 29, became the first rock book I ever read. It was convincing enough that, as a young teenager in faraway New Zealand, I began to think that maybe one day I could give this rock-critic lark a whirl. Some of these older reviewers were far loftier, though, going in for scholarly pieces that placed rock music in a broader framework of sociology and politics. Or in the case of Greil Marcus, by joining the dots of cultural archetypes, most successfully in his 1975 book, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ’n’ Roll Music.

Great or small, as the late John Peel tartly observed, all these reviewers were mainly reviewing themselves. And, really, when you thought about it, who better to furnish the invitation to do so than Bruce Springsteen? Sure, he couldn’t churn out great lyrics as dependably as Bob Dylan. And he wasn’t an ace guitarist, although his skills surely improved over time, the upward trend still evident on later records like his 2014 album High Hopes, where his tatty telecaster duels with Tom Morello’s majestic Fender Strat. Nor was he an especially versatile singer. And with the exceptions of his superb keyboardist Roy Brittan and the violinist Suki Lahav, it’s not as if he marshalled the most amazing instrumental talents around him.

Yet Springsteen did have another ace up his checked sleeve. A good artist knows something about the world that nobody else does; the great artist offers you the opportunity to be a part of it. Certainly, I saw the town Springsteen poeticised in my teenage imagination and I spent time mentally sketching out its details: it had to have tree-lined streets, naturally, and it would boast a seaside boardwalk that bustled with strolling couples and mellow poets busted for sleeping on the beach. Per Greetings from Asbury Park, the prize cultural draw would be the old carnival park where a neon-lit carousel takes ferry riders high above the shimmering lakes, the arcades, and the barefoot girls sitting on the hood of a Dodge drinking beer in the summer rain or else strapped to the backs of their boyfriends on motorcycles.

Across the Atlantic, too, this seductive vision obtained purchase with many young writers who first emerged in the 1970s clacking away for underground titles such as ZigZag and Oz, or else moonlighting for one or other of the growing number of Fleet Street supplements. Not forgetting the overground “inkies” like Melody Maker, which had editorially influenced the original Rolling Stone. Then there was the newly invigorated, trend-setting New Musical Express, whose early resident bad boy Nick Kent boldly declared that Springsteen occupied “the highest plateau of great late-20th century American songwriting.” Britain even boasted its own Cream—not a patch on the critically superior Creem, but still.

Long gone were the days when candy-flossed pop periodicals hired “journalists” indistinguishable from PR people. Or else, in the case of Queen magazine, writers who were instructed to write for a mythical woman named Caroline, who “had left school at age 16, was not an intellectual, but was the sort of person that one ended up in bed with.” So, at the shank end of the 1970s, when the NME convened its critics to determine the greatest recording at the end of a long, troubled decade, the number one gush was audible: Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, produced by one Jon Landau.

Robert Christgau was another influential reviewer who wrote a lot about Springsteen, whose music he enjoyed a lot more than the critical cult surrounding him. “I find it hard to think of him as rock and roll future,” he once admitted in the Village Voice, adding that a “doctrinal disagreement” on this score had caused ruptures in some of his closest friendships with fellow rock critics. Christgau’s hard-headed approach better reflected how rock reviewing would come to be seen by those media outlets that continued to hire their scribes into the 1980s and 1990s—not so much as contributors writing merely about themselves or to ingratiate themselves with a particular act but as specialist writers offering readers useful information on how best to spend their money.

“Creating and criticising are different things,” Christgau told me with a shrug when I met him at his cluttered apartment in the East Village. “It’s never been my experience that artists of any sort understand what criticism is about.” He had been at it long enough to know, starting out in 1967 as the “secular music” critic at Esquire before making the Village Voice the home of his famous Consumer Guide columns. To help readers with their spending decisions, Christgau would award a letter grade from A to E for a selection of the thousands of albums that made it onto his turntable each year.

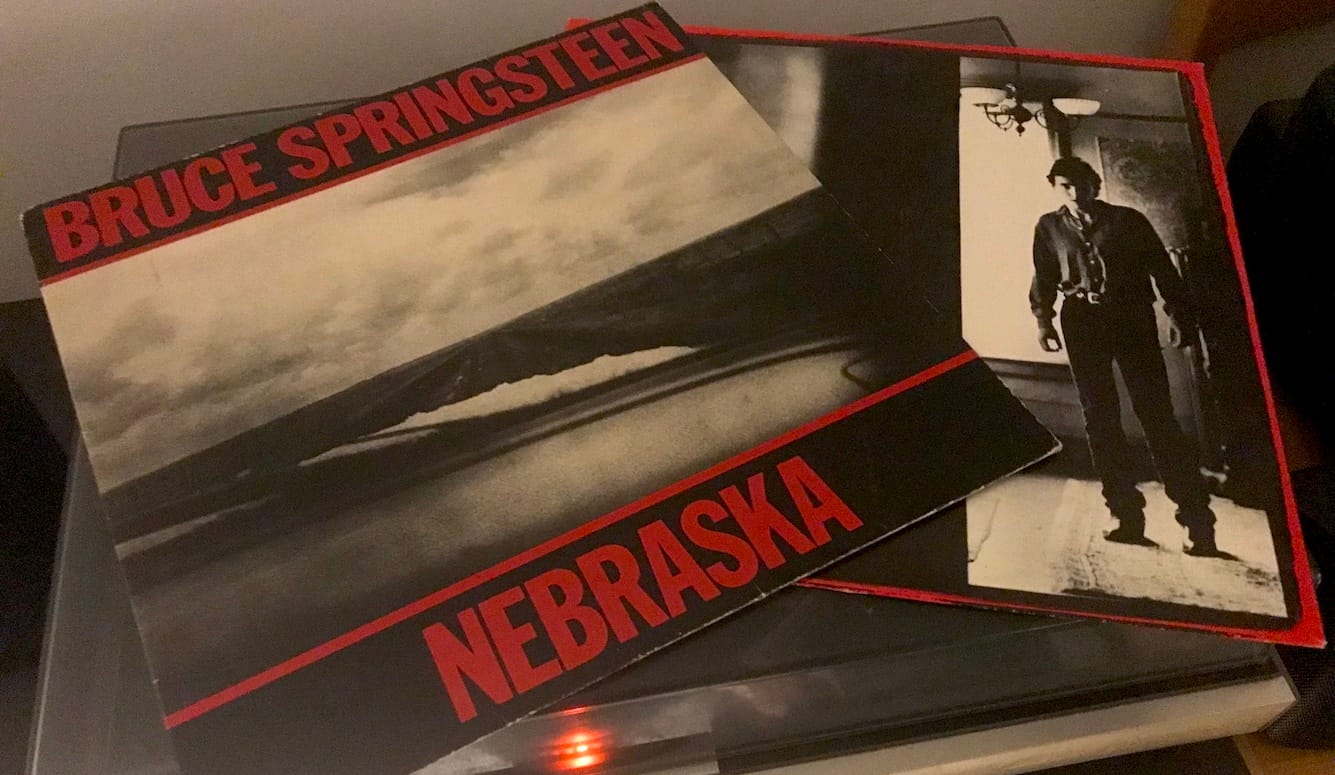

Thus, Nebraska (“Springsteen isn’t imaginative enough vocally or melodically to enrich these bitter tales of late capitalism”); Born in the USA (“rhythmically propulsive, vocally incisive, lyrically balanced, and commercially undeniable”); and, alas, The Ghost of Tom Joad (“his gift for social realist literature exceeds his gift for political music”). Christgau would listen to every new disc “at least” five times, sometimes many more, which touches on another peculiarity of rock-music reviewing in general, and Springsteen reviewing in particular. Movie critics or television writers, after all, seldom see a new movie or HBO series more than a couple of times. Ditto literary reviewers and books. But music critics will often listen to what’s deemed an important album as many as twenty times, and in Springsteen’s case probably more.

For Christgau, though, the retail value of criticism was the nub of it, a position the longevity of his column appeared to vouchsafe. “Hey,” he exclaimed, “if you put a price on it, I can put a grade on it. If you’re out in public, so am I. And if you do not accept that then you’re in the wrong business.” Also apparently in the wrong business, it transpired, was Robert Christgau. A few weeks after we met, the Village Voice canned his column, which by that point had been running for over four decades.

IV.

Still, it’s not as if the new proprietors didn’t understand the changing times. By 2006 when I interviewed Christgau, fans were downloading a lot of their music for nothing. Why hire critical gatekeepers to write about what’s freely available? And music itself was changing. Not least in the case of Springsteen, who had long since traded in all that New Jersey grease for albums that sounded decent enough most of the time but increasingly felt predictable and safe.

Nor were the famously marathon shows that beguiled the likes of Landau quite hitting the spot like they used to. A bit contrived in places, I thought when I saw him touring The Rising in 2003, full of speechifying and, in particular, ridiculously long encores that often went on for almost as long as (or in the case of at least one Australian show in 2014, longer than) the main performance.

On the other hand, perhaps this new workmanlike approach was simply a reflection of a wider culture that had moved on from its earlier dreams. “I think we’ve learned from the 1960s,” Springsteen’s longtime sideman Steve Van Zandt told me shortly before decamping from the E Street Band for a starring role in The Sopranos. “We’re more practical now. We have to work, to be awake.” Ah, but as a philosopher once asked, “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true, or is it something worse?”

One soft, infested summer a few years later, I found myself in a car with my American girlfriend crossing the New Jersey state line along the roads curving towards the musical town of my earlier imaginings. It was the time of year on the northeastern seaboard when the restaurants drag plastic chairs onto their patios and the flowers are blooming in technicolour. Or so it seemed until Little Eden finally loomed into view.

Contrary to expectations, there were no restaurants and no plastic chairs to be seen that Friday afternoon in Asbury Park. And not a lot of much else. Yeah, the fabled carousel was there in all its ragged, motionless glory, but no one seemed to be in the offing. And you know that tilt-a-whirl down on the south beach drag? Same deal. A musty-smelling fairground building (the same venue where Springsteen shot his only halfway-decent video, for the title track of his last magnificent recording, Tunnel of Love) also stood abandoned. Nor was Madame Marie’s little fortune-telling hut open for business; although possibly, who knows, that was on account of her falling afoul of the authorities.

I started to fume a bit. Where was the sign saying, “Springsteen Walking Tour Begins Here”? Where was the town’s version of Mt Rushmore? When would the Wizards start playing on the boardwalk? Perhaps they were playing over the road at the Stone Pony, the fabled club where Springsteen used to play when he started out, and which indeed seemed to have the air of squalor hinted at in the reviews of those early shows. It, too, was shut.

A little later, having exhausted these and other sightseeing possibilities, we drove out of town, stopping briefly at the outskirts for a traffic light. A rugged-looking motorcyclist and his girlfriend riding pillion idled alongside us as we all waited for the light to change. I glanced over at the young woman, blonde, short-cropped hair, alabaster complexion and dressed in the latest rage. She turned around, caught my eye, flashed a dazzling smile, and yelled an unaffected “Hey!”

Hey. Then the lights turned green, and I watched this couple on their sleek machine roar off into the distance. And I saw something else flash before my eyes, too. I saw rock and roll past, and its name was Jon Landau.

A selection of the author’s favourite less-than-obvious studio tracks by Springsteen, live versions of his best hits and cover versions by other artists:

“4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)” by Ben E. King, from the album One Step Up/Two Steps Back; “Adam Raised a Cain” from Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band Live 1975–85; “Atlantic City” cover version by The Band, from the album Jericho; “Better Days” from Lucky Town; “Cautious Man” from Tunnel of Love; “Countin’ on a Miracle” from The Rising; “I Want You” live with Suki Lahav, Main Point, 1975; “It’s Hard to be a Saint in the City” cover version and outtake from Diamond Dogs, by David Bowie; “Kingdom of Days” and “Life Itself” from Working on a Dream; “Lift Me Up” from the Limbo soundtrack; “Loose Ends” outtake from The River; “New York Serenade” from The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle; “Stolen Car” cover version by Patty Griffin, from the album Light of Day; “The Rising” cover version by Sting, 2009 Kennedy Center Honors; “There Goes My Miracle” from Western Stars; “Walk Like a Man” from Tunnel of Love; “Youngstown” from The Ghost of Tom Joad; “Zero and Blind Terry” outtake from The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle; “Thunder Road” from Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band Live 1975–85.