Best of Areo Magazine

Race Is a Spectrum. Sex Is Pretty Damn Binary

Male versus female is one of surprisingly few genuine dichotomies.

Editor’s Note: The following essay first appeared in Areo Magazine and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

In this piece, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins explains the binary nature of sex and describes the significance of this to the understanding of inheritance in general, both for Charles Darwin and for us today.

—Iona Italia

Long ago, on my father’s farm, we had a particularly bumptious, mischievous, even aggressive cow called Arusha. The herdsman, musing one day on her obstreperous behaviour, remarked, “Seems to me, Arusha is more like a cross between a bull and a cow.”

Er, yes!

Arusha came to mind recently when I was interviewed by Josh Glancy of the Sunday Times. The interview was supposed to be on my new book, Flights of Fancy—about all the ways birds, bats, pterosaurs, insects and humans can defy the mundane pull of gravity. But in addition, perhaps pressed by his editor to deliver the kind of clickbait to which birds and bats cannot rise, Glancy mentioned that I had been publicly disowned by the American Humanist Association. Having named me as their Humanist of the Year in 1996, they retrospectively negated the honour in 2021. The reason? A tweet inviting discussion about the habit of “identifying as.”

In Glancy’s words,

Back in April, Dawkins caused offence when he wondered why identifying across racial barriers is so much more difficult than across sexual barriers. He wrote: "In 2015, Rachel Dolezal, a white chapter president of NAACP [The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People], was vilified for identifying as Black. Some men choose to identify as women, and some women choose to identify as men. You will be vilified if you deny that they literally are what they identify as. Discuss."1

In 2015, Rachel Dolezal, a white chapter president of NAACP, was vilified for identifying as Black. Some men choose to identify as women, and some women choose to identify as men. You will be vilified if you deny that they literally are what they identify as.

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) April 10, 2021

Discuss.

A lifetime as an Oxford tutor has ingrained in me the Socratic habit of raising questions for discussion, often topics with a mildly paradoxical flavour, conundrums, apparent contradictions or inconsistencies that seem to need a bit of sorting out. I have continued the habit on Twitter, often ending my tweets with the word, “Discuss.” That tweet was one such. Here are two other typical examples of raising a question to stimulate discussion:

Ants communicate by slow-diffusing chemicals (pheromones). If their brains had radio-speed links, would “distributed consciousness” emerge at the colony level, while no individual ant had any conscious awareness at all? Discuss, perhaps with reference to the Internet.

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) November 13, 2021

Conjecture: “There must be a moment in history when two siblings born to the same mother were destined, one to become the ancestor of all humans and the other to become the ancestor of all wombats.”

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) November 14, 2021

Is the conjecture necessarily true? Discuss.

The second question, by the way, has the interesting property that some people think the conjecture is obviously and trivially true, others that it is obviously and trivially false—binary opposite “trivially obvious” opinions. The answer (spelled out in The Ancestor’s Tale) is that the conjecture is true but by no means obvious.

What is obvious—it is second nature to any teacher worth the name—is that inviting discussion of a question is not the same as taking a position on the answer. Nevertheless, Glancy invited me to take a position: to enter, as it were, the discussion I had initiated with my Rachel Dolezal tweet. And so I said to him the following:

Race is very much a spectrum. Most African-Americans are mixed race, so there really is a spectrum. Somebody who looks white may even call themselves black, may have a very slight [African inheritance]. People who have one great-grandparent who is Native American may call themselves Native American. Sex on the other hand is pretty damn binary. So on the face of it, it would seem easier for someone to identify as whatever race they choose. If you have one black parent and one white parent, you might think you could choose what to identify as.

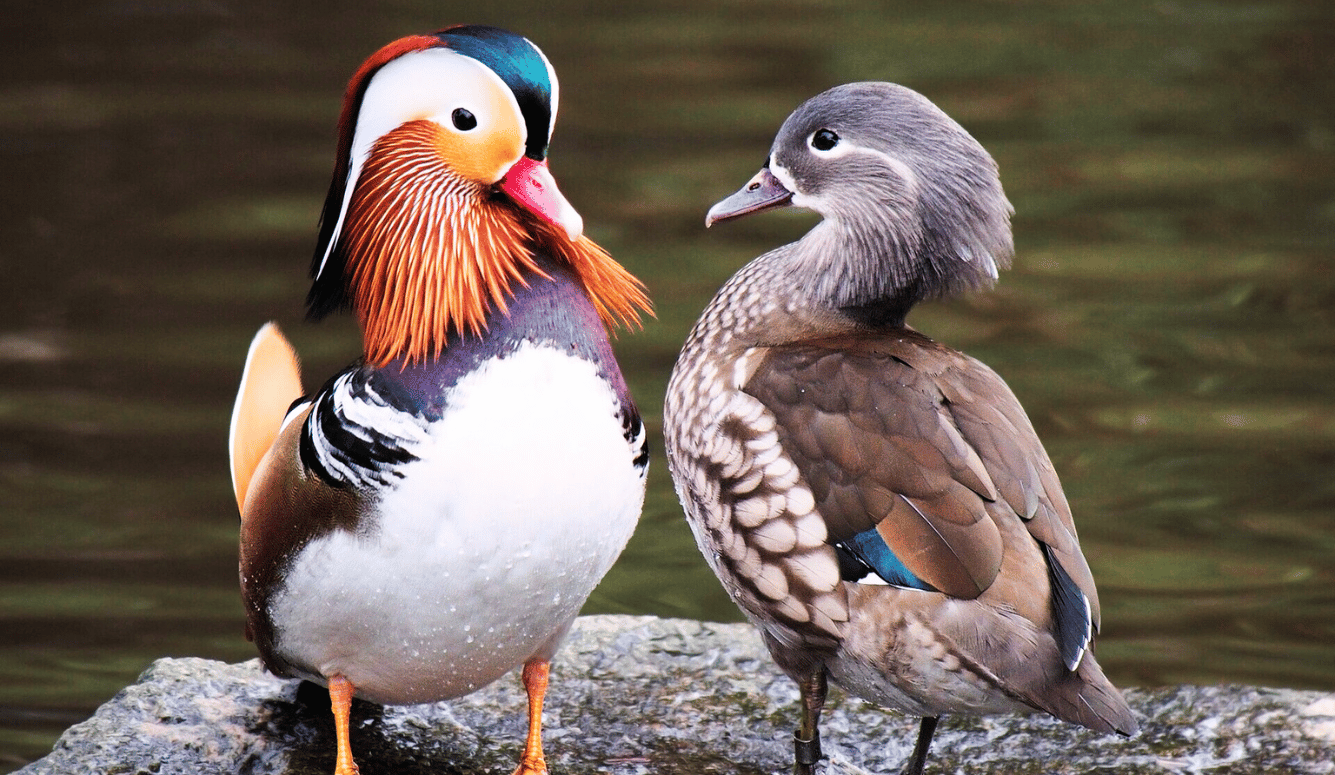

The Sunday Times condensed my words into the headline that I have adopted for this piece: Race is a spectrum. Sex is pretty damn binary. Unlike my wombat conjecture, this point really is childishly obvious. When a female and a male mate, each offspring is either female or male, extremely seldom a hermaphrodite or intersex of any kind.2 Arusha really was a cow, not a half-way bull. But her intermediate colouring made us suspect that this "pedigree Jersey" was actually half Ayrshire—an artificial insemination screw-up. When two people of different races mate, their offspring is of mixed race and this shows itself in many ways, including skin colour. After generations of intermarriage, beginning with the exploitation of enslaved women and girls, African Americans constitute a rich spectrum such that some individuals, when required to tick the "race or ethnicity" box on official forms, might justifiably feel free to "identify as" whatever they choose.

Video essay of Race Is a Spectrum. Sex Is Pretty Damn Binary: Richard Dawkins.

The Duchess of Sussex identifies as “mixed race” but is frequently referred to in the press as black. Barack Obama sees himself (and is commonly described) as black although, having one white parent, he might equally well tick the white box. The “one-drop rule,” once enshrined in the laws of some segregationist states, asserted that one drop of African “blood” was enough to make a person count as black—thus making blackness the cultural equivalent of a genetic dominant. It never worked in reverse, and it still exerts a powerful hold on American discourse—while “African Americans” actually run a smooth gamut from those of pure African descent to those with perhaps one African great great grandparent. Were race not a spectrum, Rachel Dolezal’s critics should have spotted that she wasn’t “really” black, simply by taking one look at her. It’s precisely because black Americans are a spectrum that it wasn’t obvious. With negligible exceptions, on the other hand, you can unwaveringly identify a person’s sex at a glance, especially if they remove their clothes. Sex is pretty damn binary.

If I chose to identify as a hippopotamus, you would rightly say I was being ridiculous. The claim is too facetiously at variance with reality. It’s marginally more ridiculous than the Church’s Aristotelian casuistry in identifying the “substance” of blood with wine and body with bread, while the “accidentals” safely remain an alcoholic beverage and a wafer. Not at all ridiculous, however, was James Morris’s choice to identify as a woman and his gruelling and costly transition to Jan Morris. Her explanation, in Conundrum, of how she always felt like a woman trapped in a man’s body is eloquent and moving. It rings agonizingly true and earns our deep sympathy. We rightly address her with feminine pronouns, and treat her as a woman in social interactions. We should do the same with others in her situation, honest and decent people who have wrestled all their lives with the distressing condition known as gender dysphoria.

Sex transition is an arduous revolution—physiological, anatomical, social, personal and familial—not to be undertaken lightly. I doubt that Jan Morris would have had much time for a man who simply flings on a frock and announces, “I am now a woman.” For Dr Morris, it was a ten-year odyssey. Prolonged hormone treatment, drastic surgery, readjustment of social conventions and personal relationships—those who take this plunge earn our deep respect for that very reason. And why is it so onerous and drastic, courageously worthy of such respect? Precisely because sex is so damn binary! Changing sex is a big deal. Changing the race by which you identify is a doddle in comparison, precisely because race is already a continuous spectrum, rendered so by widespread intermarriage over many generations.

Changing your “race” should be even easier if you adopt the fashionable doctrine that race is a “social construct” with no biological reality. It’s less easy with sex, to say the least. Even the most right-on sociologist might struggle to argue that a penis is a social construct. Gender theorists bypass the annoying problem of reality by decreeing that you are what you feel, regardless of biology. If you feel you are a woman, you are a woman even if you have a penis. It would seem to follow that, if feelings really are all that matter, Rachel Dolezal’s claim to feel black, regardless of biology, should merit at least a tiny modicum of sympathetic discussion, if not outright acceptance.

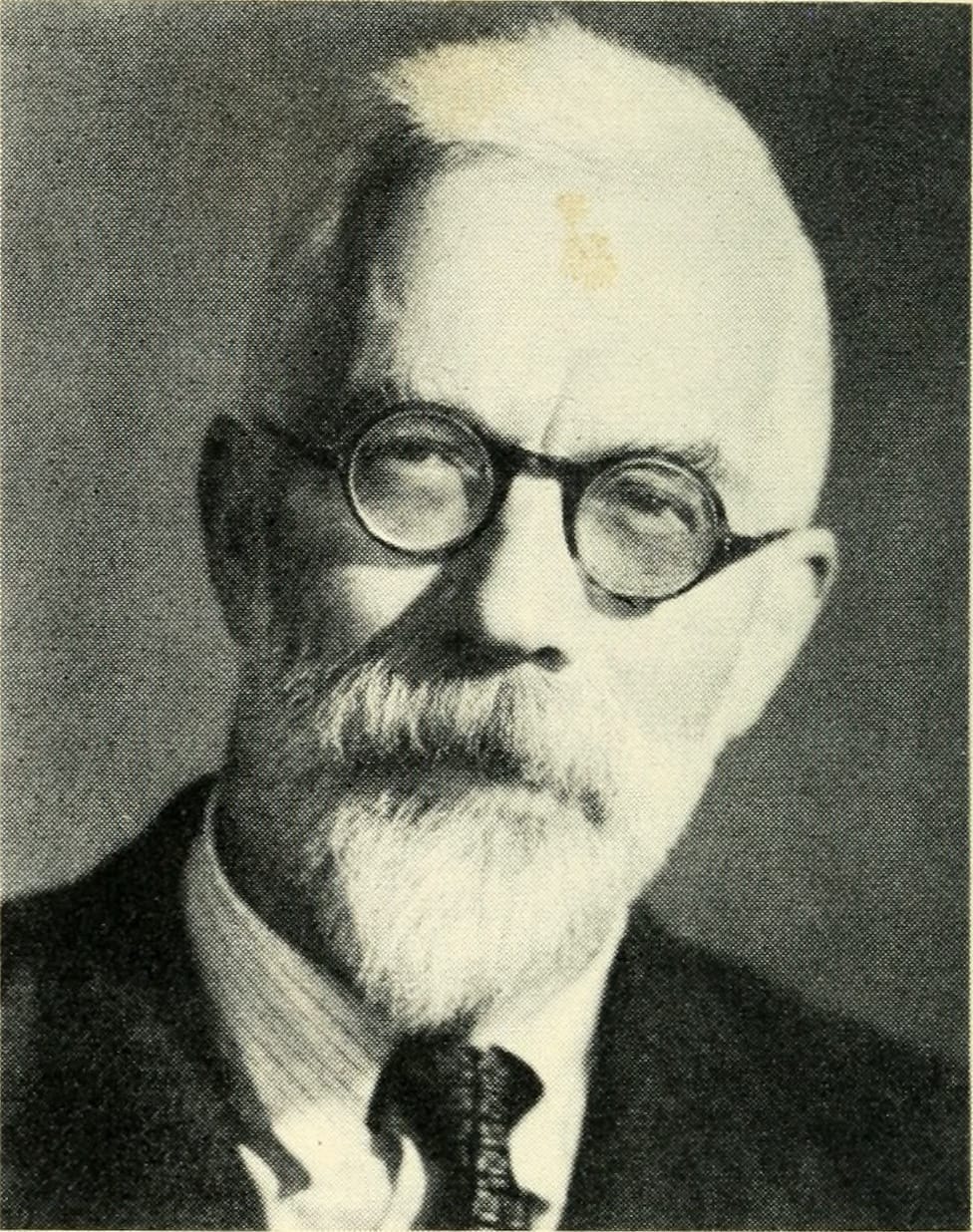

Changing the subject to something much more interesting, the binary nature of sex very nearly handed Charles Darwin the key to discovering the genetic laws now correctly attributed to Gregor Mendel. What we call “Neo-Darwinism” (see below) would not have had to wait till the twentieth century, and would indeed be just plain “Darwinism”—the great naturalist came that close. And it was the binary nature of sex that brought him there.

Darwin was troubled by an anonymous 1867 article in the North British Review, which later turned out to be by Fleeming (pronounced “Flemming”) Jenkin, a Scottish engineer who coincidentally worked on the transatlantic cable with Darwin’s other leading critic, Lord Kelvin the eminent physicist. Jenkin’s argument was couched in the horribly racist terms that were part of the intellectual wallpaper of the time, so I’ll rephrase it more neutrally to avoid distraction. A new genetic type (we’d nowadays call it a mutant) couldn’t be favoured in the long term by natural selection, said Jenkin, because it would be swamped. No matter how beneficial at first, as the generations go by it would be diluted to nothing. Darwin was convinced by the argument and it’s a shame he didn’t live to see the fallacy exposed. Jenkin and Darwin, and everybody else at the time, wrongly assumed that heredity was “blending” and that children were a kind of fluid mixture of mother and father: intermediate, like mixing paint. If you mix black with white paint you get grey, and no amount of mixing grey with grey can reconstitute the original black or white. Therefore, so the erroneous argument ran, selection can’t favour a new mutation so that it comes to dominate a population. It will be diluted out of existence as the generations go by.

It should have been noticed at the time, by the way, that Jenkin’s argument is obviously wrong. If it were right, we should all look more uniform than our grandparents’ generation—like mixing paint, then mixing it again. Jenkin should have realised that he was arguing not just against Darwin but against manifest reality.

Darwin’s acceptance of the criticism, and his consequent rowing back on his convictions, is one of several reasons why later editions of Origin of Species are inferior to the first edition. Darwin was typically right the first time. Jenkin was wrong because “blending inheritance” is false. Inheritance is Mendelian, which is the very antithesis of blending. Genes (as they are now called) are particulate. Heredity is digital, not analogue. Mixing paint is a deeply false analogy. The truth is more like shuffling black and white beads. Beads don’t blend into a grey smudge, they retain their black or white identity. Every gene in a father or mother either is, or is not, passed on to each child as a discrete, particulate entity. As the generations go by, a gene (in the form of copies) either increases or decreases in frequency. Paint doesn’t have frequency.

Although Mendel’s work was published in Darwin’s lifetime, Darwin never read it (his German wasn’t great anyway) and there’s no evidence that Mendel himself, or indeed anybody else, realised its profound significance for evolutionary theory until both Darwin and Mendel were dead. Mendel’s work was rediscovered in the early twentieth century.

The blending fallacy was immediately demonstrated mathematically by Hardy and Weinberg independently. And its significance for evolution is clearly set out in Chapter One of The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection by Sir Ronald Fisher, arguably the greatest Darwinian since Darwin. Fisher and others developed the point into what became the aforementioned Neo-Darwinism. Under Neo-Darwinism, evolution is changes in frequencies of discrete, particulate genes in population gene pools.

Intriguingly, Fisher quotes an 1857 letter from Darwin to T. H. Huxley, showing that he came near to discovering particulate inheritance himself, or at least to noticing the fallacy of “blending inheritance”:

I have lately been inclined to speculate, very crudely and indistinctly, that propagation by true fertilization will turn out to be a sort of mixture, and not true fusion, of two distinct individuals, or rather of innumerable individuals, as each parent has its parents and ancestors. I can understand on no other view the way in which crossed forms go back to so large an extent to ancestral forms. But all this, of course, is infinitely crude.

But even Fisher didn’t realise quite how tantalisingly close Darwin came to independently discovering Mendelian inheritance, indeed, even working with peas, as Mendel did. In an 1866 letter to A. R. Wallace, the co-discoverer of natural selection, Darwin writes:

My dear Wallace …

I do not think you understand what I mean by the non-blending of certain varieties … an instance will explain. I crossed the Painted Lady and Purple sweetpeas, which are very differently coloured varieties, and got, even out of the same pod, both varieties perfect but none intermediate. Something of this kind I should think must occur at least with your butterflies & the three forms of Lythrum; tho’ these cases are in appearance so wonderful, I do not know that they are really more so than every female in the world producing distinct male and female offspring...

Believe me, yours very sincerely

Ch. Darwin

The emphasis is mine. This was Darwin’s way of saying that sex is pretty damn binary. He was on the verge of generalising this to the Mendelian point that inheritance itself is pretty damn binary: every one of your genes comes from either your father or your mother. No gene is a mixture of paternal with maternal. Every gene either marches on to the next generation or it doesn’t. Genes never mix like paint. Nor does sex, and that almost gave Darwin the clue.

The reason inheritance often seems to be blending—the reason we seem to be a mixture of paternal with maternal, and the reason racial intermarriage leads to a spectrum of intermediates—is polygenes. Though every gene is particulate, lots of genes each contribute their own small effect to, for example, skin colour. And all these small effects together add up to what looks intermediate. It isn’t really like mixing paint but it looks that way if enough particulate polygenes sum up their small effects. If you mix beads it looks that way too, if the beads are small, numerous and viewed from a distance.

Anyway, the point that is relevant to this essay is that particulate, Mendelian, all-or-none, non-blending inheritance was staring Darwin, and Jenkin, and everybody else in the face. It was staring them in the face all along, in the form of the non-blending inheritance of sex. Sex is pretty damn binary. Male versus female is one of surprisingly few genuine dichotomies that can justly escape censure for what I have called “The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind.”

Discuss.

Notes

-

I am aware that Rebecca Tuvel was vilified for raising this very discussion topic, doing what academic philosophers are supposed to do, namely think. I am also only too aware of the elaborately planted minefield of constantly evolving neologisms and proliferating pronouns, through and around which academics in some humanities departments are obliged to tiptoe. Never dexterous with my toes, I am content to register awareness while ploughing on flat-footed, as a well-meaning scientist and lover of the English language. A useful map of the mine-strewn obstacle course is provided by the admirable Kathleen Stock in Material Girls: Why Reality Matters for Feminism. ↩

-

Anne Fausto-Sterling's figure of 1.7 percent intersexes is much repeated. It is inflated from the more realistic 0.018 percent by the dubious inclusion of Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome and late-onset adrenal hyperplasia. Whether you take 1.7 or 0.018 percent, the figure is still minuscule when placed in the middle of a frequency distribution, where it is dwarfed by huge peaks on either side. The distribution is overwhelmingly bimodal and sex overwhelmingly binary. ↩