Politics

Populists Before Trump

John Ganz’s lively new book provides a valuable account of the intellectual origins of Trumpism.

A review of When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s by John Ganz, 432 pages, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux (June 2024)

In the early 1990s, I was a research fellow with the Cato Institute and served as the Libertarian Party’s shadow secretary of state. It was a great time to be a believer in personal and economic liberty. After the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union collapsed, political freedom and Enlightenment values—liberal democracy, individual rights, religious freedom, free expression, and free markets—were on the march. The new zeitgeist projected a spirit of cosmopolitanism: nationalism and sectarianism were passé, while multiculturalism and globalisation reflected the shape of things to come.

We were on the cusp of a stock-market boom, unprecedented growth in information technology, and the rise of Silicon Valley as the symbol of US global economic triumph. The internet offered a free flow of information without political control, and America was marking its unipolar moment as an unchallenged superpower that could lead the world to stability and peace with multilateral cooperation, free trade, and open financial markets. I was therefore surprised to learn that celebrated libertarian economist Murray N. Rothbard was proposing an alliance between classical liberals like me and a bunch of dissident right-wingers known as “paleoconservatives.”

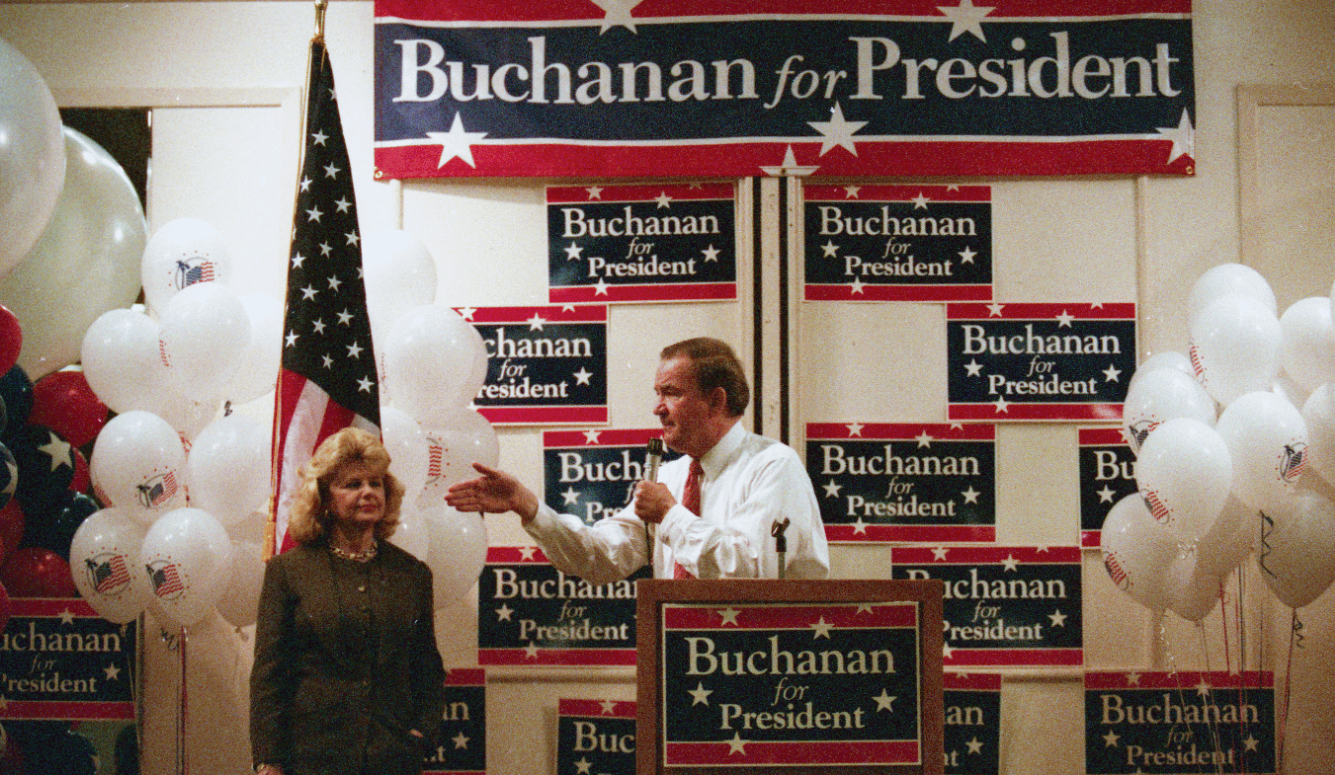

The paleocons contended that America was in peril, that liberalism was the new enemy, and that nationalism was the next big thing. As John Ganz puts it in When the Clock Broke, his new book recalling the paleocons’ intellectual and political odyssey, these thinkers believed that the US should embrace a system that would be “based on domination and exclusion, a restricted sense of community that jealously guarded its boundaries and policed its members, and the direction of a charismatic leader who would use his power to punish and prosecute for the sake of restoring lost national greatness.”