sexual assault

Violence Against Women: A Crisis in Australia?

Australia is among the least violent countries in the world. There are things we should do to make women safer, but we should not succumb to a crisis narrative.

This year, Australia has witnessed a series of terrifying crimes, which gained widespread media attention. Most shocking, perhaps, was the killing spree by Joel Cauchi at a shopping mall in Sydney’s Bondi Junction on 13 April. Cauchi stabbed six people to death, five of them women, before he was fatally shot by female police officer Amy Scott, who has been commended for her bravery. Cauchi was a deeply disturbed individual who apparently suffered from schizophrenia and had not been taking the drugs that should have kept his symptoms under control.

The public horror and concern over these events have sparked much discussion. Some have suggested that Australia is experiencing a spate of femicides—killings of women, especially by present or former romantic partners. Activists have demanded legislative and institutional reforms, to be underpinned by a formal declaration of a national emergency. Here in Australia, however, the term national emergency has a specific legal meaning relating to natural disasters, so Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has preferred to speak of a national crisis.

Every violent death is one too many. But are we really in the throes of a crisis? Let’s check some facts and figures.

Homicide in Australia over Time

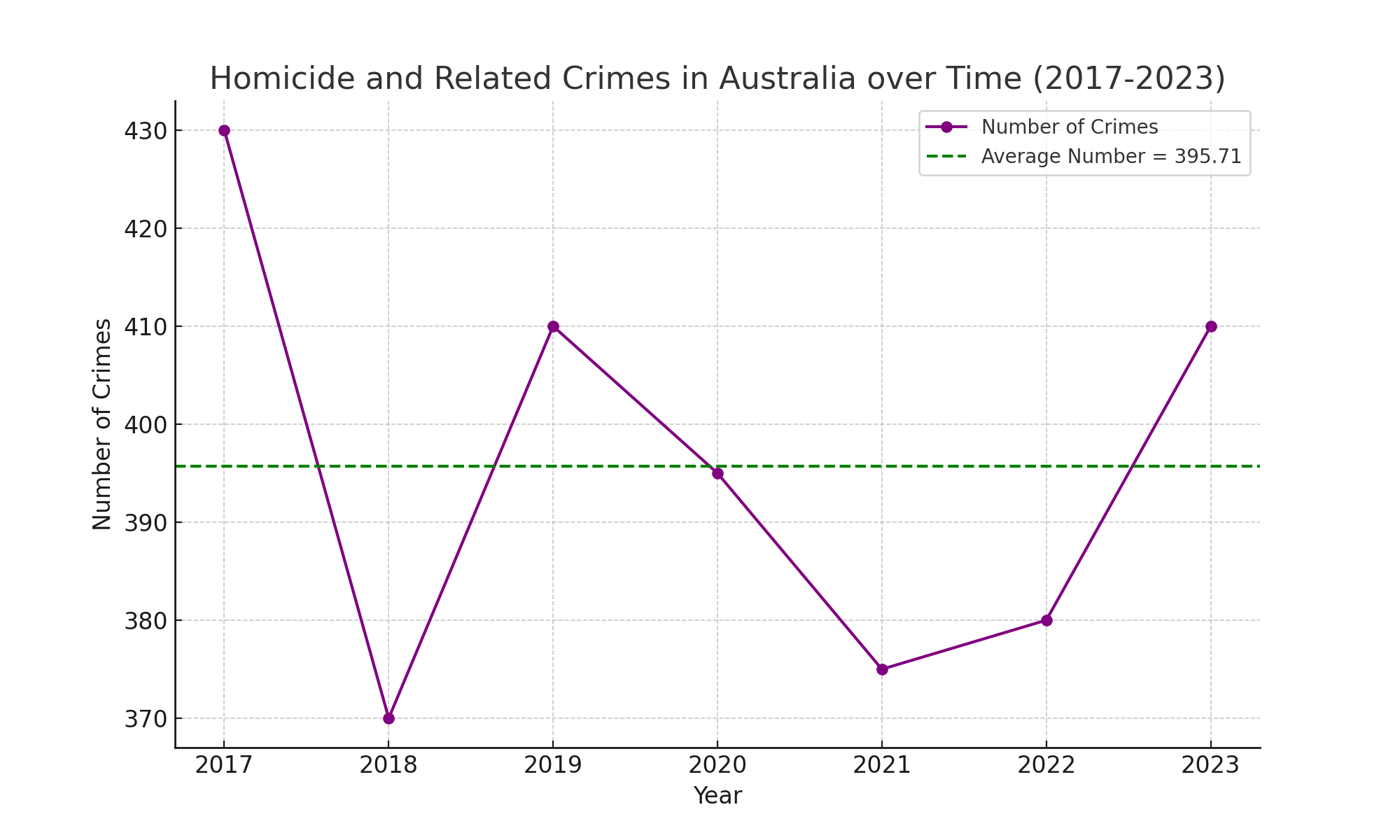

In fact, Australia’s homicide rate has been declining. There are half as many murders per year as there were just thirty years ago. There was a rise in the number of murders from 2021 to 2022, but we should put this in perspective. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there were 370 instances of “homicide and related offences” in 2021. This figure includes 193 murders, plus all recorded cases of attempted murder, and manslaughter. The equivalent statistics for 2022 show 377 crimes in this category, but they do not specify how many of these were murders. The bureau’s 2023 figures show a further increase to 409 incidents (once again, these figures do not separate out the number of murders). These numbers may appear to indicate a worrying trend, but in fact the number of these crimes has always varied unpredictably from year to year. As it happens, 2021 had the lowest crime rate in this category since at least 1993. Over the slightly longer time span of 2017–2023, the figures were: 432, 375, 416, 396, 370, 377, and 409. This looks more like a plateau than a line that’s trending upwards.

Another way of tracking homicides over time is to look at the aggregated annual statistics collected by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The UN records 193 “intentional homicides” in Australia in 2021, exactly matching the number of murders reported by the ABS. Somewhat worryingly, the UN documents 218 intentional homicides in Australia in 2022—a rise of 13 percentage points. But this is once again because the figure for 2021 was exceptionally low, and therefore it cannot be used as a fair baseline. A closer look at the UN figures confirms the impression of a plateau over the past few years.