Podcast

Podcast #244 : Language vs Reality with Nick Enfield

Iona Italia interviews linguistic anthropologist Nick Enfield about why language is good for lawyers and bad for scientists.

Iona Italia: My guest today is Nick Enfield. Nick is a linguistic anthropologist and he is Professor of Linguistics at Sydney University. He is the author of three books: Why We Talk, Consequences of Language and Language versus Reality, which is subtitled, I think, it’s Why Language is Good for Lawyers and Bad for Scientists. And it’s that latter book that we’re going to talk about today. Welcome, Nick.

Nick Enfield: Thanks for having me.

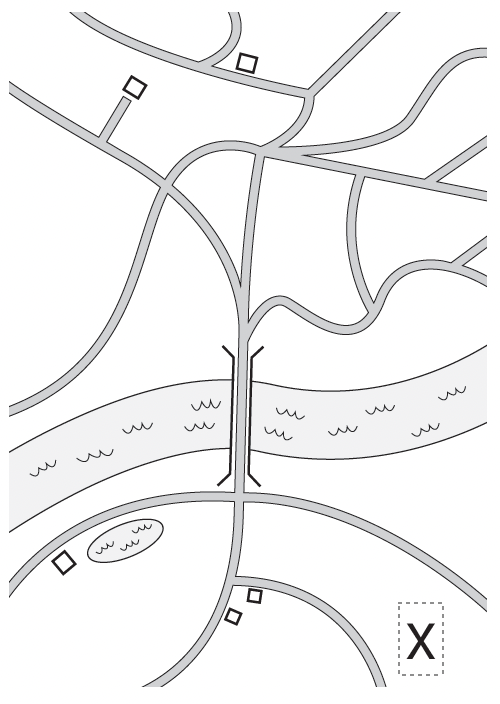

II: So, I’d like to start by looking at a concept which is central to your book. And that’s the idea that language is a means of coordination, that it’s a tool that’s used in coordination games between people. And for this concept, you lean quite heavily on an idea that was pioneered by the economist Thomas Schelling from the 1960s. And Schelling’s idea is probably most easily illustrated with an example that he gives of two parachutists. So, two parachutists land in enemy territory and they’ve got to find each other and meet up and they both have a map of the territory and they each know that the other person has that map as well. And in the centre of the map is a bridge across a river, and all of the local roads are leading to that bridge. So the two parachutists, each independently, without being able to communicate with each other, are likely to go and meet on that bridge. The bridge in that example is known as a Schelling point.

So, it’s the opposite of the prisoner’s dilemma in that this kind of coordination depends upon agreeing on certain conspicuous landmarks that are not only conspicuous to you, but that you know and understand will also be striking and salient to other people.

I’m going to read a little passage from the book in which you talk about Schelling games and their relevance to how we use language.

Imagine you are participating in an experiment. The experimenter puts you in a room on your own and tells you that you have a partner in the experiment, someone you’ve never met, who is sitting in a room nearby, also on his own. You have no way to communicate with that person. Here is your instruction:

You are to divide $100 into two piles, labeled A and B. Your partner is to divide another $100 into two piles labeled A and B. If you allot the same amounts to A and B, respectively, that your partner does, each of you gets $100; if your count differs from his, neither of you gets anything.

Can you guess what the most popular solution is? That’s right. 90% of people in Schelling’s experiment converged on the obvious: fifty-fifty.

(I really want to know about the other 10% of people, those crazy guys.)

Schelling’s coordination problems are famous for showing that strangers are able to converge in brand-new situations with no discussion or conferral. Solutions to Schelling’s games have something in common: the thing that people coordinate around will always have “some kind of prominence or conspicuousness.” That conspicuousness should be apparent to both parties. Recall that there is only one bridge on the map in figure 1.1. It is near the center of the image and most roads lead to it.

(So you give an illustration of Schelling’s original map that he imagines the two parachutists having. That’s the figure 1.1.)

People readily see it as the best thing to coordinate around. This is not just because people find the bridge prominent. It is because they understand that anybody else would also recognize this prominence. You might wonder how often in everyday life you are faced with a coordination game of this kind. The answer is: all the time. Every time you talk to somebody. Language is our most important tool for achieving social coordination and using language is itself a coordination game. Becoming highly practiced at using language means recognizing the prominent features that word meanings provide, just as the parachutists’ map provides prominent landmarks for anyone who looks. And with language, as with the parachutists, the map is shared and known to be shared.

This point underpins one of the central ideas I want to convey in this book. The idea is that words and other bits of language are none other than highly practiced solutions to coordination games.

So, can you say more about what that means for how we should understand language and maybe give some examples of how this functions?

NE: Sure. Well, Schelling was coming out of an interest in conflict in developing his ideas of coordination games because he saw that in conflict situations, people were … for example, one army is figuring out how am I going to attack this other army and take them by surprise. There’s a lot of thinking about how the other is thinking about how I am thinking. It’s a sort of higher level theory of mind, if you like. And that kind of level of theory of mind is important for either conflict or cooperation. And he was really focused on how that worked from a game theory point of view. And he wasn’t specifically looking at language per se.

But I think really the reason why I foregrounded that work by Schelling in the beginning of the book is that I want to highlight the fact that language is not just about conveying information. It’s a tool that we use for coordinating with other people. So the function of it is really to try and influence others, nudge them, guide them, even manipulate them, depending on the situation, into having certain thoughts, into having certain responses in ways that typically are mutually beneficial so when I’m talking to you, I’m trying, we’re trying to align and converge and that to me is a key function of language and information is a means to that end rather than being the key function of language.

So when I look at this in the book I mean I guess one thing that’s interesting and it’s important to distinguish is between the resources of language itself, the words, for example, in the dictionary; those are really something like Schelling’s map. And we all walk around with these kinds of reference points at our disposal. And so we can refer to them in some sense whenever we’re talking to each other so that we know the kind of thing that other people are trying to do.

So one of the things I talk about in the book is just a very simple everyday word, the word ‘spoon.’ And this is referring back to work by Roger Brown, a famous social psychologist who looked at how kids learn language. And he pointed out that, you can even take a simple word like ‘spoon.’ And one of the interesting, magical things about words is that they capture infinite diversity in the world with some very simple category. And his point was that with ‘spoon’ … you can have a million different objects which would fit the description of ‘spoon.’ But what’s important is that that word will function in social interaction, in communication, to serve the purposes that we have that matter to us most every day. So, you will say something like ‘Pass me a spoon.’ And that shows, he points out, that we don’t care about the differences between spoons, but we care about the differences between spoons on the one hand and forks on the other and that’s something specific to our culture. So ,you go to another culture and you might find that they don’t have much use for spoons. So you can find in their language some kind of reflection of that.

So, one big piece about the Schelling idea is that through a history of a community, the way that people coordinate their activities results in categories being shared in some sense. And then this leads to conventions, which, in fact, save you the trouble of having to solve coordination problems on the fly. But at the same time, we don’t just speak in words. I don’t just say a single word to you: we say phrases and sentences, which you will not have ever heard before. So, we’re always working with unique and brand new novel utterances and that is much more like the Schelling problems, which are unique situations where I’ve got to find where you are, knowing that you’re trying to guide me there, if you know what I mean. And that sort of higher level operation of trying to think about what you’re trying to get me to think about is crucial in language and it highlights coordination rather than simple information transfer as being the key thing.

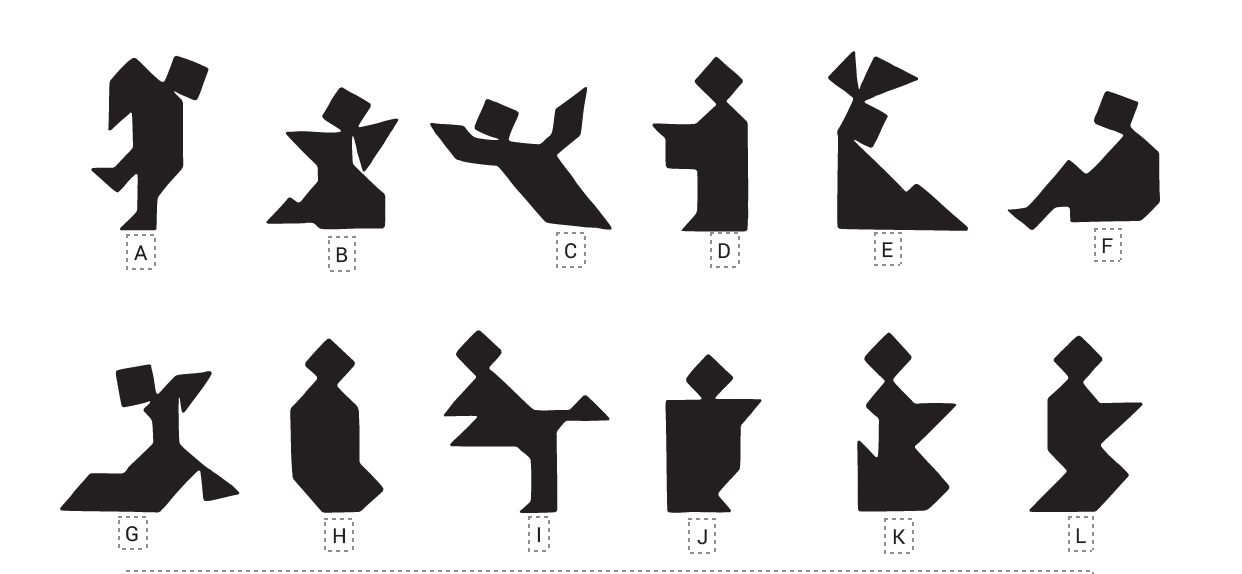

II: Yeah, you also gave this example of tangram figures, which are these geometrical figures, but they look a little bit like human figures. And the game with the tangram figures is that you both have the figures in front of you, but you can’t see each other’s tangram cards.

NE: Right.

II: And one person has to order them and the other person gives them instructions as to how to order them. So they have to describe each of the tangram figures and it becomes, “There’s one of them [tangram I in the illustration above] that looks a little bit … and they’re just geometric forms … but if you squinted at it carefully, it might look like a person skating with their hands out in front of them. So it’s relying on a kind of version of—is it called pareidolia, where we tend to see human faces and figures in abstract objects? And in the first iterations of the game, the person will say, ‘Well, it’s got four shapes and it looks a bit like a skater, but with the two arms stretched in front of them and like an ice skater, like the ice skater in that famous painting in the Edinburgh Portrait Gallery of the parish priest skating with his leg up behind him. So that’s a very long-winded description. And then in the second iteration, people will just say, ‘the ice skater,’ and you already know which one that’s referring to. And later they will just say, ‘next the skater.’ So we converge also on the description that is the most economical for what we want to convey. Otherwise we’re going to end up like in Borges’ story, “Funes, el Memorioso.” Do you know that story? I’m not sure what it’s called in English [“Funes, the Memorious” (1944)] … the rememberer, his problem is that he remembers absolutely everything. So every object and being is unique to him. And not only is every dog unique, but also the dog at that specific time of day viewed from that particular angle, etc. So, it’s the opposite of that. We want to converge on something … rather than conveying in the most accurate way what’s in our minds, that conveys the least information necessary to just identify the object.

NE: In that example, the one about the tangram figures and the ice skater, this is a classic cognitive psychology experiment where the people who are participating are given a task and the task is to order those figures, as you said. So it’s very specific kind of task that they have to solve. And as you point out, very quickly they go from long-winded attempts to coordinate and eventually they coordinate and they can signal to each other. Quickly, it gets very economical because the purpose is very specific and given to them. So, you know, all I have to do is pick out the object.

But most of life is not really like that and most of what we want to do with language is not really like that and this is an important thing that … I think it’s a much more important theme in the book. And that is that, if only everything were as simple as saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to call it the skater’ and then the problem is solved. And all we have to do is say ‘the skater’ and then we know how to pick the object out. That is economical, as you point out, and it saves a lot of trouble for those two people in the experiment. At the other end of the scale, you’ve got the crazy situation and the short story that you mentioned where you have no power of categorisation or generalisation at all and that would be completely impossible. But the middle ground is where we mostly are in life and what we find ourselves doing with language is not only trying to get people to identify objects, that’s obviously important, but we’re often inviting them to take a stance towards those objects and to share a perspective on those objects. So, going for different framings.

So very standard examples would be something like distinguishing between terrorists versus freedom fighters. Now, when I’m talking about a particular set of individuals who have fired rocket launches, I’m not just trying to get you to identify the referent as a basic function of language as in the tangram experiment. What I’m trying to get you to do is to take the same stance as me or to understand the stance that I’m inviting you to take so that we can then coordinate in some sense. So that comes back to the Schelling point, which is to say: reference is not the only thing I want you to do.

And this comes back to the subtitle that you pointed out for the book is that if we were just scientists trying to get each other to see facts and objects in the world, our language would just have little labels. But instead, we’re more like lawyers, and we’re trying to convince, we’re trying to persuade, we’re trying to get people to align to our view. And language is a wonderful tool for that, precisely because it doesn’t simply identify. What it also does is evaluate a colour and shade. And our language gives us many different options for that. And that’s the thing that you’ll recall George Orwell in 1984 was warning against, that you can’t really operate with a language if you only get one word for good. What you need is a whole range of different shades so that you can choose them according to the situation. And it’s that context specificity that I think is so important for trying to figure out what are the right words to use on a given occasion.

II: So, this idea that it’s not about trying to convey, or it’s not primarily about trying to convey, the image that is in my mind from my mind into your mind, like a kind of Vulcan mind meld. It’s not about that. It’s much more about coordination around categories, around categorisation.

You talk about a really interesting phenomenon in the book, which is called verbal overshadowing, whereby when we’re invited to categorise objects, we are not only generalising about those objects to other people. So, if I say, ‘I’m going to go grab a spoon’ to you, you don’t know what kind of spoon I’m going to get. You don’t know if it will be a large spoon, a teaspoon, a serving spoon, a wooden spoon. And you certainly don’t know what individual spoon I’m going to get, exactly what design of spoons we have in our house. But it doesn’t matter. I just want to convey the idea of spoons to you. But it’s more than that. In fact, when people are asked to categorise, they end up forgetting some of the detail about the individual objects. Do you want to talk about that? So you say that “in verbal overshadowing, our use of language overwrites our own memories.” I find this fascinating.

NE: Sure. Well, the beginning of the idea is really in the idea of categorisation, which is that you, as you just said, with spoons and any other word for objects like chairs and dogs and lamps and so on, you group many things together that have all sorts of individual differences, but you discard them for the purpose of the category, right? So, ‘we need some chairs’ means, ‘I don’t really mind if they’re plastic or wood or whatever; we just we need these things that people can sit on.’ So it’s useful in the way that I just suggested. And for that purpose, categories are very high functioning. They operate at two levels. One is that you have categories as an individual cognitive agent, you use categories to reduce the amount of the cognitive load of just getting around the world. You want to distinguish between things to eat versus things not to eat and things to run away from and so on as efficiently as you can. So, there’s something individually useful about having categories.

But labels for categories in languages are not just private things. They exist because people need them for these kinds of public coordination games. And there’s an interaction between those two types of categories, which is what you’re talking about now. So in the verbal overshadowing studies, what those studies focused on was things, perceptions, or experiences that were quite hard to put into words. So for example, people’s faces … we’re very good at recognising different individuals. We remember faces really well. We’re obviously perceptually very prone to zooming in on faces and so on. But we’re quite bad at describing faces. So, I can show you an image, a photograph of someone and you can remember their face immediately and find them in a crowd. But if I try to describe that person’s face, you can’t easily take my words and identify a person based on those words. So there’s something poor about our language for these kinds of things, the faces being one example.

An example of one of these experiments would be that you take people in a psych experiment, you show them a video of a bank robbery, and they see the face of the perpetrator quite clearly. And the people who see this clip, you break them into two groups, and in one group, you immediately ask them to describe the face in as much detail as they possibly can.

And the other group, you give them some other unrelated task and you don’t give them an opportunity to talk about the face. And then later what you do is you give both groups … you show them a lineup of faces and you say, ‘okay, could you pick out the perpetrator from this set of faces?’ And it turns out that the people who described the face using words are worse at recognising the perpetrator’s face. The ones who were not given an opportunity to talk about it, to encode in words the face that they saw, they were actually better at remembering this face. This has been replicated and it’s been shown to hold for other things like tastes and other kinds of visual experience.

And it’s an amazing effect because you would think this is a terrible down side to categories. It certainly is. There’s a real lesson there in terms of eyewitness accounts and how much you really want to get people to talk about what they’ve seen if they need to later identify details about it.

But that’s a rare situation for most people. So the costs of verbal overshadowing most of the time are not that great. For example, you talked about going and getting a spoon. Well, who cares which spoon it is as long as I can spoon my sugar into my coffee with it. And it’s fine for me to discard that information and that’s the upside of categories is that they allow me to be more efficient in my cognitive processing. I’ll chuck information away. But in these particular kinds of cases such as eyewitness accounts, it’s a very high cost that you pay.

II: Yeah, I find it fascinating as a writer that the people who described things were less able to recognise and identify them later. That was also true of colours. That no matter how much we might like a specific shade of colour or how good our colour acuity might be in a test, if you actually need to match the colour you’re never going to rely on a description or your memory. You’re going to use … you’re going to bring a swatch or use Pantone numbers. Or if you’re doing graphic design, you put in a hex number if it’s important that the colours are matched. If it’s important that the colours are matched, then there’s no way you can rely on your subjective memory. Even though my feeling is always that I remember exactly what colour it was and I have a strong feeling about the specific shade of colour, but then when I go to pick it out and I compare it and I look at the hex number compared with what I thought that the colour was, it always suddenly looks completely different to me than the memory I’ve constructed when I’ve verbalised the description.

NE: Yeah, I mean, I think what’s important here is that the memory is poor, but the key thing that I’m emphasising here is that it’s much worse if you’ve relied on coding what you saw using language.

So, one of the ideas that I talk about in the book is that reality is very much more complex and shaded than we possibly could have access to. Our perceptual apparatus is only captures a narrow bandwidth of the real world, as it were, and that’s fine because that’s what we’ve evolved to survive in and we can get by perfectly well with a relatively narrow bandwidth. but it’s still much more detail that our perceptual apparatus gives us than what our languages can deliver to us—or rather, than what our languages can encode. So I can perceive, on certain measures, more than a million just noticeable differences in colour, but no language has anything remotely near that number of distinctions that can be made. Most languages only have a basic colour vocabulary of a dozen or so words. So what we’ve got then is a kind of two-stage simplification of the world where our biology gives us a first step of real reduction of detail in some sense and then our language chops that down much, much further and that’s what we have to work with when it comes to coordinating with others.

II: So, there’s two different kinds of reality in a sense, and one can be influenced by language and the other cannot. There’s brute force reality and there’s social reality. I actually want to just find this passage. Here we are:

Language has a complicated relationship with reality. One reason is that reality comes in two kinds. Brute reality—in the realm of natural causes—can be captured by language only in the most partial, subjective and fragmentary ways. It isn’t affected by whether we talk about it or by how we choose to describe it or frame it. By complete contrast, social reality, the realm of rights, duties and institutions cannot exist without language. …

... The philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe introduced this distinction between brute and social reality by comparing two ways of describing a single situation. She imagines that someone delivers a shipment of potatoes to her house. Two descriptions are: (1) He had potatoes carted to my house and left there and (2) The potatoes came into my possession. The first sentence is a physical description of a person’s movements … It describes brute reality, things that can be physically observed. The second sentence describes a different kind of reality. You would not …

[Laughing.] Sorry, I find this very funny.

You would not be able to tell by physically examining the potatoes who they belong to.

I’m just imagining somebody carving their names, labelling the potatoes. I’ve had some flatmates in the past who might have done that.

The potatoes are edible when cooked. They can block someone’s path. These are matters of brute reality. But when we say that somebody has the right to cook and eat them or the duty to move them out of the way, we are talking about social reality … social interpersonal agreements about ownership, agreements that are created, or at least backed up by, language.

The relation between the two realities is not symmetrical. Legalities are a classic example of social reality. But how are laws upheld? By the threat of physical force. Brute reality. This is why political power—mostly a matter of institutionalized rights and duties—is ultimately grounded in physical facts. A baton to the head will hurt, no matter who you vote for …. Whether force is legitimate can be contested (as social reality), but the physical effects of the force cannot. …

Ownership, for example, can readily be negotiated—rendered untrue, if you like—by the use of force and its nonnegotiable effects. If someone with a knife deprives me of my rights to the cash in my wallet, this works because of the physical fact that the knife would cause me harm. A mugger’s power to overturn the social fact of ownership comes directly from physical facts. I can contest it by producing a bigger knife. Or if I threaten the mugger with prosecution, this again is based in physical facts—the brute denial of physical freedom by imprisonment.

I thought that was a lovely explanation.

NE: Thank you. Yeah, I think this distinction is really important and it is complicated when we talk about language. At a first level, I think it’s crucial to distinguish between brute reality and social reality in the way that you’ve just said. But we’re sort of forced to deal with language when we talk about brute reality in a way that I think a lot of this book really is about. That distinction is made very nicely by the philosopher John Searle, who in one of his introductions of that idea, the example of brute reality that he gives is that there is snow on Mount Everest. Social reality would be things like, ‘I am licensed to drive in California.’ That is a fact that’s created by language in some sense, but he says that the fact that there is snow on Mount Everest is not created by language.

I want to say yes and no. I think he’s absolutely right in a certain intuitive sense. There’s some cold white stuff on the top of a place that we call Mount Everest and it doesn’t matter what we say, it’s still there. But how do you test that claim? Well, you have to go through language to test it. So if I can test that idea, I say, ‘No, there’s no snow on Mount Everest.’ How would we go and check? Well, we have to have a definition of ‘snow’ and not all languages have that word. Some languages will distinguish between kinds of snow and some languages will just have one word that captures ice and snow and other things, words for precipitation or what have you. You suddenly get into this problem of … we have an intuition that there’s brute reality, but we have to get through the social reality that is our language in order to test it out. And that takes us to the real problem that scientists have to deal with is that they’re interested in in brute reality, but they can’t coordinate their activities around it unless they’re working through the social reality of linguistic categories themselves.

So I think I didn’t... I’m not sure if I made that really clear enough, but the key thing I want to say about language itself is that language itself, even though it uses brute reality to exist … I mean, you have to be able to hear or see me if you’re going to understand what I’m saying, that’s a matter of brute reality, but the meanings of the words, these maps for coordination, these categories for aligning with each other, those things are the product of social realities in the sense that they are products of human activity in the past and essentially human agreement.

Now it’s not that we, you and I or any other two people agreed that these words I’m using right now are going to have the meanings they have, but it’s effectively the same thing because people have treated these words as having the meanings that they have, then we can rely on them to have those meanings, going back to Schelling’s kind of coordination. So there’s on the one hand a very important set of reasons to distinguish brute and social reality but on the other hand this great complication through language bridging the two.

II: You talk about later in the book that there are some ways in which brute reality constraints are the way that we categorise things using language, and there are other types of categorisation that are completely, that are purely social. So for example, you say that most languages have words that distinguish between walking and running. They might not exactly have a word for walk and a word for run. They might divide that up into more categories, but they will have some way of discriminating between a gait that is walking and a gait that is running. Nature has certain discontinuities. It’s not just one mush and we can’t slice it up in any way we fancy. So it’s always going to be … we’re always going to find it easier to distinguish between blue and red. So if I say something is red, you will have an idea that it’s not blue. But if I say ‘it’s not burgundy, it’s more kind of maroon,’ you being a man will have no idea what I’m talking about.

So, reality presents us with certain divides, it snaps at certain joints, basically. But then there are other categories that we decide, divisions that we decide are important or not important socially. For example, is it important to know … if I say that this person is my aunt, is it important to know whether she was my mother’s sister or my father’s sister? And whether, if she was my mother’s sister, was she my mother’s younger sister or my mother’s older sister? Which are all distinctions that you can make in most Indian languages, but not in English.

NE: Yeah, look, if we go backwards from the last point that you made, the example of the kinship systems I think is a really great one, which shows the power of language to direct our attention and to determine aspects of the discourse that we’re engaged in. So kinship is obviously one important domain of brute reality, but it’s imbued with social values and social categorisations and the example of ‘aunt’ is a great one because you know from many languages’ point of view English is impoverished and it makes it difficult for you to readily go straight to those distinctions of father’s older sister and mother’s younger sister, this kind of thing. Some languages allow you to very efficiently get to that. Plenty of languages have four words for what we call ‘aunt’ in English. The downside of having a language like that is that you can’t gloss over that distinction. You’re forced to make that distinction. You’re forced to state whether … and therefore you’re not just forced to state whether a person was the older or younger sibling of the father or mother, but you’re forced to find that out and to pay attention to that. And so it actually directs your attention. Where I work in Southeast Asia, where I studied languages intensively, they have systems of exactly this kind. And you find that oftentimes people need to find out information about how old people are relative to other people. And they’ll have a whole vocabulary that will direct them in that, to those distinctions. But you see then that there are collateral effects of having fine distinctions in language systems because they give you extra work in some interesting sense.

Going back to the first question, the first point you made about nature having discontinuities or joints where it will snap. And you gave the example of walking to running. So that was from an experiment where you see a person on a treadmill and the treadmill slowly gets faster and faster and at a certain point the person what we would call ‘breaks into a run’ and a whole number of aspects of their physical movement change at the same time. So that’s a good example of a salient perceptual distinction which is captured in languages. It would be the first distinction you’d see languages making and then after that distinction they may go finer and distinguish between jogging and sprinting and these other kinds of things. But I would want to emphasise that it’s not that nature just gives you this distinction. There’s no reason for you to put it in the language. As an individual agent who has perception of the world, you could notice anything you want, and we can. We’re capable of noticing all sorts of things. The question is not about whether nature delivers some distinction to my perception. The question is why then does that enter into my language?

And this takes us back to this coordination issue. So if the walking versus running distinction is the most salient one, perceptually or experientially, in some sense, then, it’s exactly like that bridge in the middle of the map that Schelling gave to his subjects. So it’s something that is mutually apparent and is an available point for coordination and that’s where we’re going to gravitate to first if we’re trying to distinguish between someone was on this side of that border or that side of that border in terms of running versus walking. So really the distinction enters language through the fact that we’ve played coordination games that have drawn on that perceptual distinction delivered by reality. It’s not a direct line from the reality to the language.

II: There are also occasions in which the language forces you to make distinctions that you might not otherwise make. So, for example, in English you can say, ‘I met my friend yesterday.’ But you can’t say that in German. You have to specify whether it was a male or female friend that you met and in English you don’t have to specify.

NE: Yeah, English gives you the same... That may be true with ‘friend,’ but this is obviously changing at the moment with pronouns. English has gender in its pronouns and so oftentimes, you can avoid specifying whether someone was male or female, but it becomes quite marked, it becomes quite hearable in a sense that you are avoiding it. So, most of the time through pronouns, when you’re talking about people in the third person, you’re going to also reveal whether it’s a male or female. And we got to the point where, as writers, we are given ways to avoid that. Let’s use plural, you know, become ‘they’ and so forth if that’s what we’re trying to do. And that’s a really important fact about language. Gender is just one example, but you could look at all sorts of areas, tense marking for example—some languages don’t require you to mark past and future in the same ways that other languages do. Kinship was another example we just mentioned.

So, the possibility of specifying something is valuable just as the possibility of eliding or avoiding specifying something is valuable and neither should really be a default. So there are benefits and costs to both of those. And I’d say typically languages are fairly well calibrated to the kind of cultural settings that they get used in. It’s just that there’s often a lag between the categories that we’ve inherited from the past, which make up the languages we learn, and the values of the present, which can grate a little against those conventions.

II: I want to talk a little bit towards the end here about narrative and stories. So, in the last couple of chapters of your book, you turn from language in its more real-world settings to language within literature and to how stories are structured. And you have some absolutely fascinating things to say about what you consider to be the archetypal story, why it is that way. And also why it is that we might enjoy hearing, in particular, stories of adversity. Do you want to talk about that a bit?

NE: Sure, so, in this section of the book, as you say, the last few chapters, I got really immersed in a lot of the literature about stories and about narrative and firstly, how they’re structured, because that was intellectually interesting to me, just as someone who writes for a living, I found that fascinating, but obviously then thinking about what stories really do to us.

Now, the theme of this book is really about how we use language to influence others and to guide them and to potentially manipulate them. And the more I looked at stories, the more I realised just how powerful a grip they have on us. I have kids who are now 10 and 11 and they were, I don’t know, six and seven around the time that I was writing this book. We were reading Roald Dahl stories and all sorts of stories of that kind. And it allowed me to really see just how you hear a story, as soon as it gets kicked off, then you’re bought into it. You really want to hear what happens. You can see it when you’re talking to kids and reading stories together, you really see how the story gets a grip on them. And when it’s a book it’s fascinating. With movies, you might say, ‘well, you know, there’s always imagery and all this visual excitement and so on that captures you.’ But a book, it’s just words. I mean, Roald Dahl has nice little pictures, of course. But you just pick up a novel and it’s just words and it can transport you.

Now that transportation, I talk quite a bit about that in the book, what that means. It’s this situation where you become less aware of your surroundings, you become invested in the characters, you forget where you are and what time it is, and you want to know what happens to this person. And that is because, of course, stories are really built around a person to whom things happen and a person that has goals and that is trying to reach those goals. So in those chapters in the book, I look partly at the fact that stories are structured in that way, that there are these really quite reliable aspects of the structure of a story, the way it begins, the way it gets set up.

But then I get into this literature around, firstly, how do stories actually affect you? So, all of these neurotransmitters are released as we read or experience stories. That partly accounts for why we have nice feelings when we’re under narrative transportation. But it also accounts for why we have a very … why we often get a sense of collective wellbeing, particularly when we share stories with other people.

The other really important piece that I try to emphasise in the book is that stories are really important for building collective sense-making. That’s obviously a really big part of the lawyerly function of language, that is that I’m trying to bring you to my point of view. I’m trying to join you to my mission. I’m trying to get you to see the world in the same way that I see it. I’m not just trying to communicate something to you. So, in that part of the book, we’re seeing how we can go from the amazing little facts around the categories of words and sentences up to this much more rich way of packaging, of using language as a way of building that commonality and that coordination. Narrative in the general sense could mean something like collective sense making and building a similar vision of the world. And I mean that, but what I really tried to get into in the book is more the structure of stories that absolutely takes over our attention. And it’s something that...

The last thing I want to emphasise is that it’s something that is not only about Hollywood screenplays and novels. Those are very extreme versions of how stories can capture us. But when you look at everyday interaction and you look at how people talk throughout their day, one of the things we do all the time is tell these little stories. And they might just be a 20-second story about some what some idiot did on the bus this morning or some way in which a work colleague annoyed me or something or something that delighted me. But I will still set it up as a story by getting you to understand what I’m going for, how I want you to react, and then we’ll go through the story. And then at the end, hopefully, if you are on my side, then you’ll react as I’ve set it up. If it’s a joke, you’ll laugh. If it’s something that was awful for me, you’ll give me some sympathy or what have you. And so these stories not only affect us in this interesting kind of cognitive ways, but they also are a very important mechanism for creating social glue. And that’s the case all the way from the deepest, most extensive literature all the way to everyday gossip.

II: Yeah, it’s an example of that … it’s a lovely quotation from Wittgenstein, which you use in the book, “Sometimes we measure in order to test the ruler.” So it’s also a way of showing something about yourself and testing something about the other person and their reactions. I was struck by a couple of things, and one is that in the book you talk about the idea that fiction is a kind of “flight simulator for the mind.” I thought that was brilliant. So there is this perennial problem, philosophical problem, which is why do we enjoy consuming stories about things that are frightening, horrifying, or tragic? Why do we get pleasure out of creating such stories and consuming such stories about things that would be awful if they happened to us in real life? You examine a couple of interesting theories, one being that it provides excitement without danger. So it stimulates some of the same endorphins that you would have in a dangerous situation, but without actually exposing yourself to any danger. So it’s like animals at play, play-hunting. I thought that was a really interesting idea.

I also liked the way you talked about the structure of stories and among other things, you say that the main characters in stories usually suffer adversity. And you write,

Why do main characters suffer such adversity? Because adversity creates a deep need in a person. And that need becomes a central driver behind the arc of any compelling story. As observers, we are especially tuned into the goals and needs of our heroes and heroines, and this often works on more than one level. In a typical Hollywood screenplay, the main character will have two simultaneous goals. One is quite concrete and specific. The other is much deeper, more personal, and of greater consequence.

On the surface, these characters try to reach some defined, immediate objective. They might be trying to solve a crime, kill a beast, secure an artifact or escape a monster. But they will always have an underlying and more important goal. Their surface actions must address their deeper need.

I love that. That there’s the outer quest and the inner quest.

NE: Yeah, this is a frequent trope about Hollywood screenplays and novels in general that there’s what the story’s about and what it’s really about. And what it’s really about is addressing that deep need. Once you see that and then you look at stories, you re-watch movies or you re-read novels, you start to see that distinction. And I think it’s a really useful one. And that deep need … what’s important I think is that that is somehow independent of the surface structure of the story. The story, as you just said in the quote, could be a detective story or could be Mad Max or anything. But the underlying needs are fundamental to what it means to be human and we all have some pretty basic things that we’re dealing with and places we want to get to and different stories that give us interestingly different ways to get there.

Sport is another example of that. You can watch a game, and you have no idea how it’s going to end. You might have some sense and you certainly know the rules that it’s going to be played by. It’s a bit like a film genre, but you’ve got a very strong sense of who the people are and what they want, and what’s at stake. So that is something we can take part in vicariously.

And the point you made about the flight simulator idea, I agree that’s a lovely way of putting it. It’s not my way of putting it, I’m quoting others on that. The facts, I think, are really telling there. So, I cite in the book a study that showed … it looked at a large number of novels, 20th-century novels, and they found that the rate at which people get murdered in novels is many orders greater than the rate at which people get murdered in everyday life.

II: Thank goodness.

NE: They found 11% of characters, I think it was, in these novels get killed. So, we’re very much interested in experiencing what people experience or accessing what people experience in these very intense situations in life. And if a movie or a novel didn’t become intense or wild in some way, it would be boring, right? It wouldn’t be interesting for us to look at. So I think that works partly just on the level of the cheesecake theory of movies … that somehow, you know, evolutionarily …

II: Isn’t that music, the theory of cognitive cheesecake? I think it’s Steven Pinker’s phrase.

NE: Yeah, that’s right. So the same idea would be … maybe we just enjoy it because there’s some evolutionary basis for that. But I think it’s more complex than that because nobody really wants lots of violence, to experience it as such. But what you’re pointing out is that, if stories are violent or challenging or intense or tragic, scary, whatever it may be, extreme, I think would be the general, the common thread there, it allows us to mentally simulate or to imagine, or to try out how we might react in some kinds of situation. I think it’s one function of stories. I think for me, that’s the way it is.

It’s not every day that we watch a horror movie. It’s not every day that we watch an extreme film. But it is every day that we tell each other little stories about who said what, who did what, what happened to me in my day. And those things should always have some little lesson. Those things will always have some little instructive moral about what’s normal, what we both agree is bad or good, and they give us opportunities to align with each other. What I end up focusing on there is that function of stories, which is coordinative, coming back to the overall theme that you started with, with Schelling.

II: I saw on Twitter the other day someone tweeted … this went completely viral, that she says, ‘I was at a wedding and one of the guests asked if the maid of honour was single.’ And that’s all it says in the tweet, nothing else at all.

went to a wedding & watched this guy ask the bride if the maid of honor was single

— Rona Wang (@ronawang) May 24, 2024

It’s a micro-story, an anecdote. She passes no judgment. She makes no commentary at all. But the fact that she singles this out for comment in itself makes a comment, which is that she clearly thinks this is out of the ordinary and probably bad, i.e. going against the conventions in a situation in which conventions should absolutely be followed, a wedding. There were thousands of angry comments about her, about the judgmentalism and lack of empathy, etc. that she showed. It was really interesting because she made no commentary at all. She simply made a remark, but remarks are not neutral.

NE: No, exactly. One of the things I discussed in the book is that stories of the kind that we tell each other every day are always, should always centre around some kind of disruption, some kind of wrinkle in what is normal or unremarkable. So, as you point out, the very fact that it gets remarked on, the very fact that it gets told about is itself premised on this being somehow a departure from expectation. That’s an interesting example. I didn’t see that one. One of the key things with a story is that you’re trying to invite someone to take the same stance as you. So typically, if you’re launching a story, you’ll be able to hear from the person’s delivery that they think this was a terrible thing or they think this was a cute thing or they think … you’ll get a sense of how they view the story. You just said that in this particular tweet, the person made no evaluation. Well, of course that’s because there’s no … you can’t hear their intonation. You don’t get a lot of the information that you would normally get from their delivery. So for better or worse, that person may have been misinterpreted or they may have been interpreted correctly, who knows. And of course Twitter is a weird situation where you’re inviting alignment or disalignment from some massive number of complete strangers. But normally if you’re in your circle of friends, if you’re with the people that you’re normally with, then even the most oblique of references will be understood just right. It’ll be understood as remarking on a disruption or a wrinkle, but also how we are supposed to feel about this. And when you align and you say, ‘my God, that’s terrible’ or whatever you say, if you can come in with the right, the same perspective that I was in, that I had, with only the most subtle of kind of cues to get there, then we’ve managed to display our attunement really well and that’s often times what stories allow us to do.

II: It’s interesting that you’re also quite … towards the end of the book, you’re very much emphasising the negative aspects of language. And you write:

We do not coordinate around reality but around versions of reality hewn by words. The result is awkward for the scientist but convenient for the lawyer. A problem is that we naturally take our word-given versions of the world to be reliable. And when we feel that we understand something clearly, this has a “thought-terminating” effect, as the philosopher C.T. Nguyen puts it: “A sense of confusion is a signal that we need to think more. But when things feel clear to us, we are satisfied.” This creates a kind of cognitive vulnerability that allows people to be manipulated by any system of thought that is “seductively clear.” …

…language itself is one such seductively clear system. In fact, it is the seductively clear system with its thousands of problem-solving, information-discarding, thought-terminating conventional categories. … In this way, a language is not only a source of attention-directing frames and moorings for social coordination, it is a great collection of off-switches for the mind.

I was very struck by that phrase, “a great collection of off-switches for the mind.” Explain yourself.

NE: It’s funny that you said this is negative and as you read it, the way you’ve just framed it, I can understand why you would put it that way. I guess my purpose in doing this, putting it that way is to really highlight the need for mindfulness. What I try to do in the book is make the case that language directs us in various ways, captures us in various ways, we discard information in various ways. We touched on a number of these things in this conversation. The book goes into a lot of detail around that. So I think the case is clear that language does have those effects. And I guess what I’m trying to do in the end is to summarise by emphasising that in fairly strong terms as a kind of warning or as an incentive, maybe put it that way, to being truly mindful about how we use language.

If you accept that language is “a great collection of off-switches for the mind,” which is to say, it gives us comforting categories that we latch onto and that allow us to overlook a whole lot of things that are actually there to be known about, then we’re just allowing it to kind of wash us along in its conventional channels of flow. And oftentimes that’s fine. But a lot of the time it’s not fine, particularly if you’re a scientist, a.k.a. truth seeker, a.k.a scout. You’re looking for information about how the world is. So if that’s what you’re engaged in at a given time, that’s where you really need to... I don’t know, be reminded, as I was trying to do in that passage, be reminded of the power of language, not to make you think certain things, but to more make you not think or not notice certain things. That’s really what’s behind me trying to push that, is to say, ‘Be careful. Think about the fact that your language is giving you one quite fragmentary set of categories for thinking and coordinating with others.’ The beauty of language is that we can be endlessly creative with it. We can be highly specific. We can say things in 10 different ways. And we should be doing that. We should be using every bit of creative freedom that our language gives us to go beyond those little maps that we happen to share and actually triangulate and actually get to the bottom of how things are. It’s not a prison, it doesn’t stop us from thinking things, but it can effectively do that if we don’t use it mindfully. And that’s where I try to land at the end of the book.

II: It presents us with tempting shortcuts, perhaps.

NE: That’s a good way to put it. Yes, tempting shortcuts. We are creatures of … we minimise effort wherever we can and that’s only natural. Often, that’s fine and good. But when I’m trying to highlight the idea that we’re seeking knowledge and to do that, it takes work, it’s not the context in which you want to cut corners. It’s not the context in which you want to minimise effort. It requires great effort, and that means resisting those temptations just to go with the flow of the maps you’ve been handed.

II: I think that’s a great place to end. Thank you so much, Nick.

NE: Thanks very much for having me.

II: My pleasure.