Quillette Cetera

My Cousin, el Periodista

A trip down memory lane with a Mexican-American journalist who went from captioning pin-ups at his father’s tabloid as a teenager to leading Univision’s online operations.

As many Canadian readers know, I’m not the only journalist in my family: my mother Barbara is a popular weekly columnist at a Toronto-based daily newspaper called the National Post. But what no one knows is that my family tree boasts two other journalists, father and son, both of whom had more interesting careers than either me or my mother.

By way of explanation, a few paragraphs of family background are in order.

My father Ronald (now better known in Montreal’s finer delis as “Ronny”) grew up in China, the only child of Arthur and Marika Kupitsky—Jews who’d fled Russia’s murderous pogroms only to face new terrors following Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. After World War II, the three of them escaped to Canada, where they built a new life—one that would eventually include me and my younger sister Joanne.

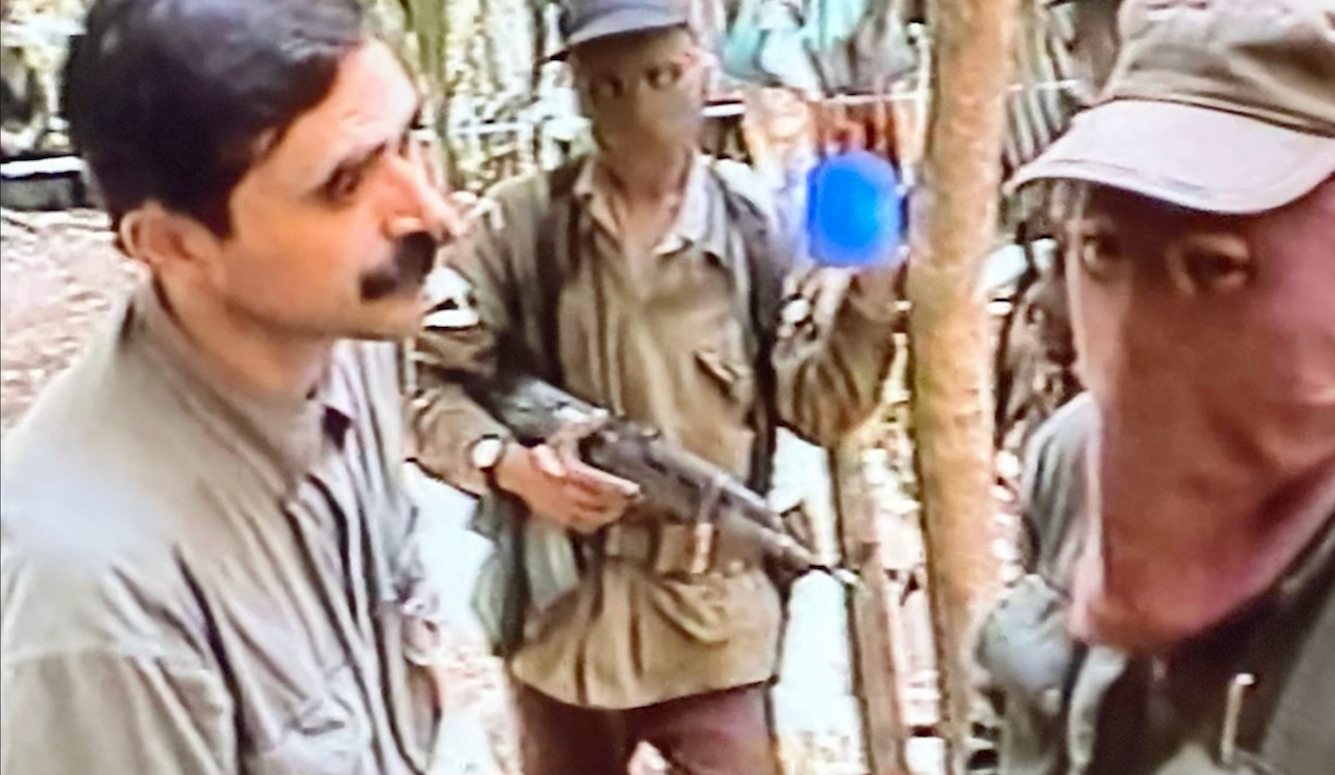

But my father wasn’t Arthur’s only child. My paternal grandfather also had a daughter, Marina, from a first wife who’d died during childbirth. While the rest of the family put down roots in Quebec, Marina found her way to Mexico City, became a professional astrologer, and, like some character from a novel, took up with a bullfighter-turned-salesman named Jorge López Antúnez. (For reasons that I am yet to learn, his bullfighting name was El Estudiante—“the student.”)

My aunt (who followed Jorge into the grave just two years ago, at the ripe old age of 94) possessed a sharp mind and an independent spirit. A highly cultured speaker of Russian, English, French, Italian, German, and Spanish, Marina also happened to be something of a snob. Unimpressed with Jorge’s transition from bullfighter to salesman, she told him he’d need to find a less pedestrian line of work if he wanted her hand in marriage.

Seeking to become a man of letters, Jorge enlisted with an upstart Mexican newspaper called Ovaciones. While he had no formal training beyond a high-school education, the ex-bullfighter showed a flair for picking popular stories and crafting attention-grabbing headlines. And within the space of little more than a decade, he’d become the newspaper’s editor-in-chief. Under his tenure, the afternoon edition’s daily circulation shot up from 35,000 to more than a quarter million.

But despite Jorge’s success, I’m guessing Marina had mixed feelings, as Ovaciones’ rise was fuelled by decidedly downmarket innovations. These included a daily Page-3 pin-up-girl feature—invariably depicting a busty young woman with a big smile, photographed in a bathing suit, tight-fitting dress, or novelty costume. So yes, Jorge had become a “knowledge worker” (as the modern expression goes). But Ovaciones wasn’t exactly Mexico’s answer to Le Figaro.

By this time, Jorge and Marina had two sons—the eldest of whom, Bruno, would start making regular visits to his dad’s office. Being still in his early teens, Bruno wasn’t qualified to do much more than empty wastebaskets, change typewriter ribbons, and serve Cuba Libres to the reporters (“who gave good tips,” he recalls). But as would later become apparent, my cousin did possess an indispensable job skill: Thanks to his polyglot mother’s tutelage, Bruno was the only member of the newsroom staff—of any age—who spoke fluent English (with the exception of a dissolute chain-smoking British ex-pat who, by Bruno’s description, called in sick as often as not).

Earlier this month, I caught up with my cousin at a family reunion he’d organized in the Mexican town of Tepoztlán, where I pressed him for more details about his early days in the profession back in the 1970s. I say pressed because, like other old-school journos, Bruno is far more comfortable telling other people’s stories than his own.

One new tidbit I learned is that while Jorge had originally been happy to have his son hang around the Ovaciones offices as a visitor, he was utterly horrified when Bruno started talking about pursuing journalism as a vocation. Channelling Harry Truman’s comment about politics, Jorge told Bruno, “I’d prefer you worked as a pianist in a bordello.”

It’s a turn of phrase I repeat here not only because it’s funny, but because the old-timey film image it summons to mind helps illustrate just how deep into journalism’s pre-digital era Bruno’s professional roots go.

Bruno listened carefully to his father’s advice, but remained unpersuaded. By now, he’d caught the journalism bug, and older workers were taking the boss’ son under their wings.

One of these was an archives editor who happened to be well-connected with Mexico’s powerful journalist union, the Sindicato Nacional de Redactores de la Prensa (SNRP), which then remained steeped in the revolutionary slogans of Soviet-era socialism. Bruno still remembers the day when this editor dragged him to an SNRP meeting. The pair sat through the proceedings until the chair put out a call for new union recruits who possessed suitably zealous revolutionary fervour. Bruno’s colleague stood up and declared that, why yes, he happened to have just such a fellow right there in the room with them.

Thus was Bruno formally ordained a union man (or boy, I suppose). And when he showed up at Ovaciones the following week, his own father was powerless to dismiss him without incurring the SNRP’s wrath.

As a member of the editorial staff, Bruno would be tasked with monitoring the incoming English-language wire services. In the process, this newsroom rookie—still just 16 years old—effectively became editor of the paper’s aforementioned girly-pic feature, since the photos that appeared on page 3 were also plucked from international feeds.

And this is what led Bruno to his first ethical dilemma as a journalist. His job required that he not only pick the photos, but also that he write up Spanish-language captions. The problem was that these wire-circulated pin-up images didn’t come with identifying information. And without captions, the photos wouldn’t qualify (even in the most nominal terms) as journalism. They’d just be smut.

“Be creative” was Jorge’s advice when Bruno came to his father for guidance. Jorge was professionally rigorous when it came to important investigative stories, and did what he could to resist owners’ demands to publish government-friendly propaganda. But he took a far more casual attitude to crowd-pleasing filler. Surely, the editor-in-chief told his son, a skilled journalist could scan such photos for aesthetic clues that betrayed the subject’s personality and interests—perhaps even her name.

And so Bruno returned to his desk and got to work. A woman in a beret with a smouldering rive-gauche gaze became “Suzette,” an aspiring artist who loved romantic walks down the Seine. The next day’s selection, in pigtails and freckles, was Daisy, a Texas rose with a passion for football and country music.

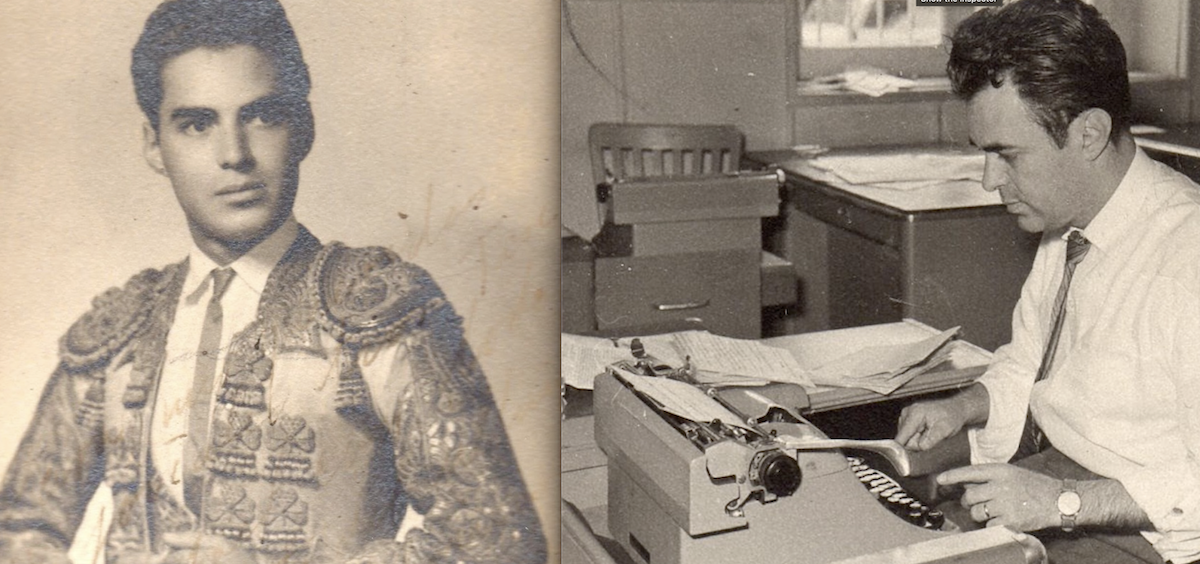

Okay, so not Pulitzer Prize-grade material. But it would prove to be an early step on a glittering five-decade career path that would take Bruno to UPI, The Arizona Republic, CNN, and corner-office jobs at Univision, where he’d serve as VP of online operations until 2011. Combining his mother’s cultural sophistication with his father’s real-world newsroom savvy, Bruno became that model Kipling-esque journalist who could interview kings (of sorts) without losing the common touch.

At one point, Bruno really did try to quit the world of Mexican journalism, whose corrupt elements had begun revealing themselves. But an academic foray into archaeology was upended by a student strike at his university, coupled with a warning from a professor who explained what kind of moral compromises many Mexican researchers then had to make in order to earn a living. Bruno learned that not all the brown paper envelopes trading hands in the country were full of cash. Some contained precious Mexican artifacts destined for American buyers.

My cousin’s fortunes took a major uptick when he won a journalistic fellowship at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. The program had Bruno travelling around the United States, interviewing high-profile politicians and academics. He became a workaholic (a lifelong trait, it turned out), and sent a steady stream of stories back to Ovaciones. In time, he also became a stringer for American wire services, breaking big stories on both sides of the Mexico–US border, including a few that required real courage to report.

In 1981, while travelling in the Chiapas region, Bruno stumbled on the funeral of several Guatemalan refugees who, it turned out, had been murdered by the Guatemalan army on Mexican soil. Fernando Romeo Lucas García’s Guatemalan regime was then using brutal counterinsurgency tactics—which included burning down towns whose residents were suspected of anti-government sympathies, and then (as Bruno’s groundbreaking report showed) pursuing survivors who’d fled across the border. His UPI news story shocked audiences not only in Mexico, but also the United States, partly because the Guatemalan military tactics that Bruno described had been adapted from those developed by the American military during the Vietnam War.

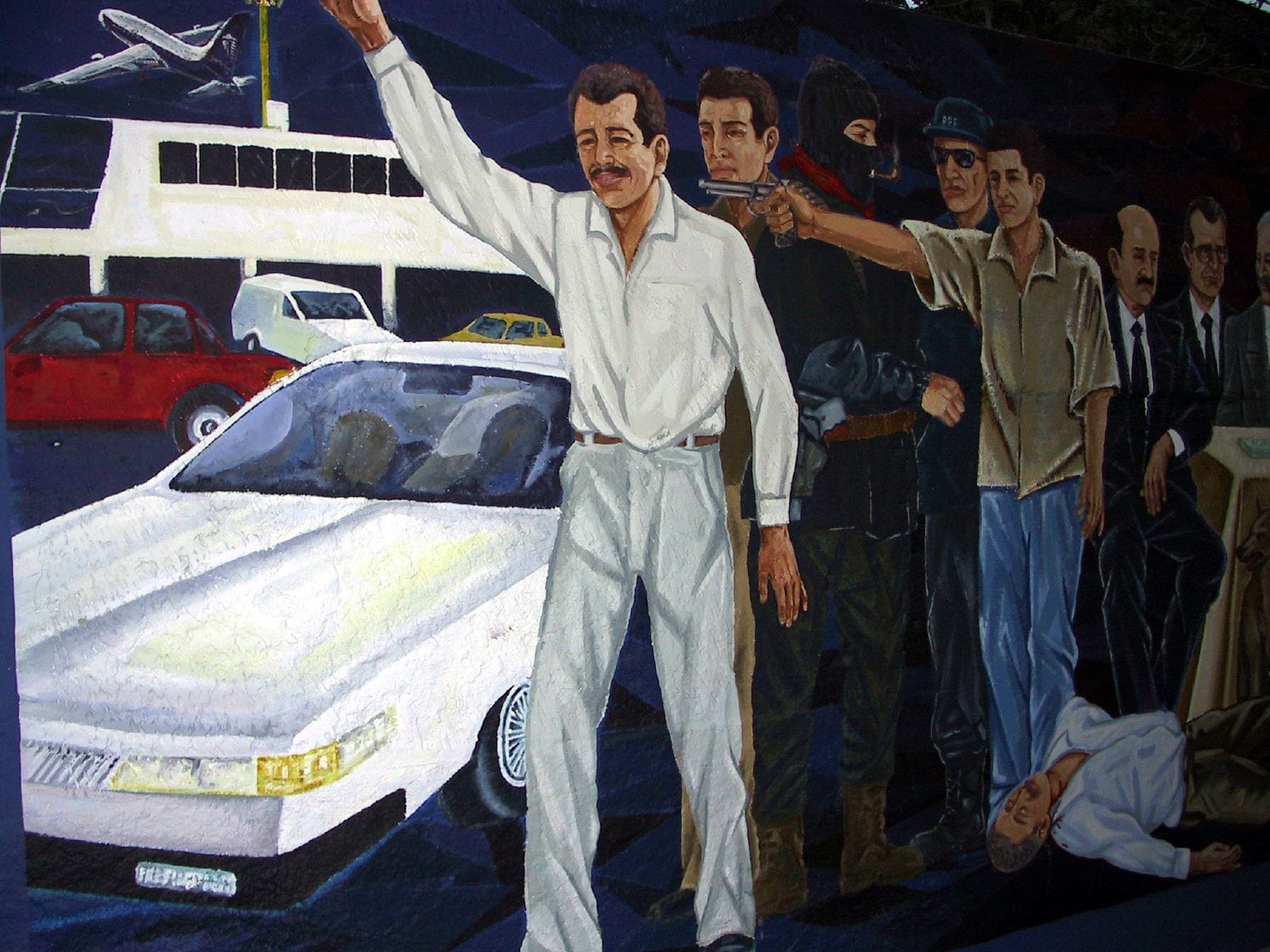

In 1994, Bruno did the last television interview with Mexican presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio Murrieta, just a day before he was murdered in Tijuana. A year later, Bruno’s Emmy-nominated reporting exposed details surrounding the Aguas Blancas massacre, in which police gunned down peasants staging a protest to demand fertiliser subsidies. Government officers had sought to cast the victims as armed criminals, even going so far as to plant guns around their corpses. But Bruno convinced eyewitnesses to come forward, and secured exclusive access to a video shot by a police cameraman showing how the victims had been targeted.

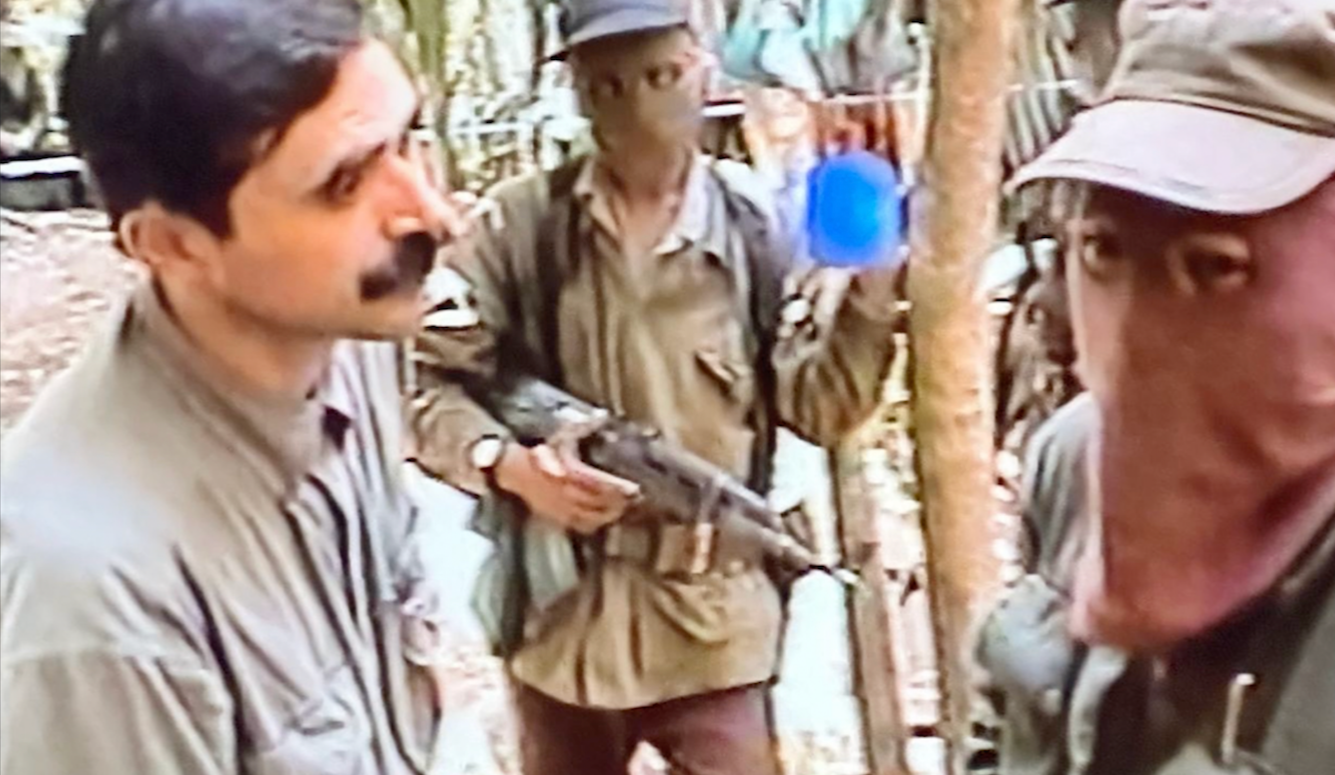

Two years after that, he accompanied a group of Maoist Popular Revolutionary Army guerrillas (blindfolded, I might add) to their mountain redoubt in Guerrero, where he interviewed their leader on camera. (He had to make the trip alone, but, charmer that he is, somehow convinced one of the guerrillas to act as cameraman.) It’s a precedent that humbles me whenever someone flatters me as “brave” for staking out a controversial position in a column or tweet.

Bruno retired from the field in 2011, and now works as a consultant and corporate advisor. But journalism is obviously still in his blood. At our recent reunion, he could be spotted with a mic in his hand and a cameraman in tow, asking aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, and cousins—including me—about their family memories.

While these weren’t quite the hard-hitting interview on which Bruno had built his reputation, it was great to see my older cousin in his element—in part because it offered a possible glimpse into my own future life as a retired ex-journalist. Much like the pianist who keeps joyously belting out tunes long after the bordello’s been shuttered, dedicated journalists never really stop reporting on the world. They just stop charging others for the privilege.