Art and Culture

Art over Man: The Roger Waters Test Case

When we create art, we are our best selves, better than the selves we are outside of art.

In February 1980, aged fifteen, I found myself at the Nassau Coliseum in Long Island watching a spectacular performance of Pink Floyd’s The Wall. I didn’t even know the band. I had to be talked into going by my friend Richie, who had scalped tickets for $75 each, which was an enormous sum for a teenager at the time. I received a brisk education in the venue parking lot, where a stranger we met played us his old Pink Floyd tapes and told us the story of Syd Barrett, the band’s founder whose mental breakdown had inspired The Wall. Later, I would learn that the album was as much about Roger Waters, who was then the band’s frontman, but it hardly mattered. I was hooked.

Over 26 tracks, The Wall tells the story of a musician named Pink, a sensitive young man mocked at school by his teachers, traumatised by an overbearing mother, used by the establishment, and let down by his lovers. It was not my story, but the alienated rage, the haunted isolation, and the flight into the imagination all struck a chord in me. Over the next few years, I’d wallpaper my bedroom with Pink Floyd posters and work my way through their entire back-catalogue, from Animals through Wish You Were Here to the comically strange Ummagumma and their debut LP Piper at the Gates of Dawn, which was the band’s only record with Syd Barrett.

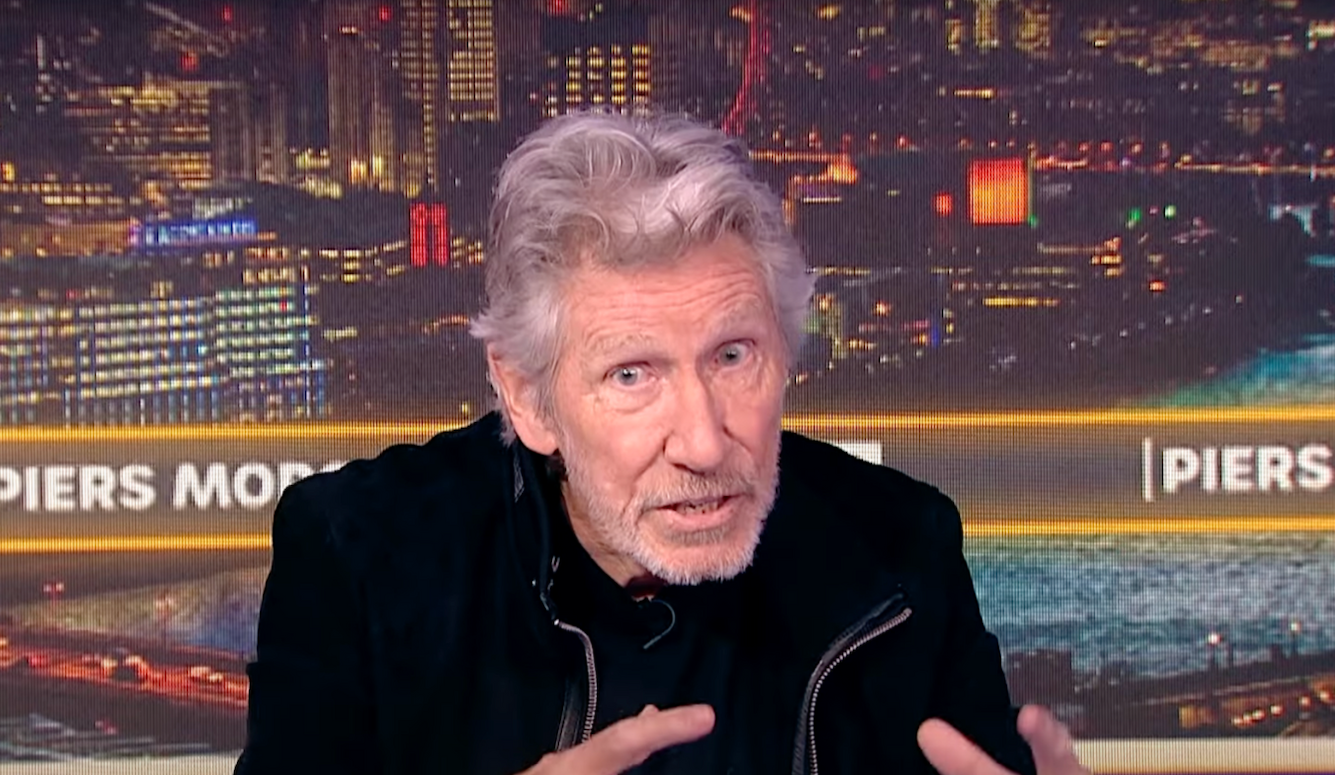

Forty-four years later, I’m a different man. Today, I’m a husband and a father, I’m an observant Jew not a Christian, I’m married to an Israeli, and I have developed deep attachments to Judaism and Israel, a country about which I knew next to nothing when I was fifteen. I like to believe that Roger Waters today is also a very different man from the one who authored the soundtrack of my adolescence. This week, Waters appeared on Piers Morgan Uncensored and flatly denied that Hamas had raped Israeli women on 7 October. Those who claim otherwise, he told his host, are spreading “filthy, disgusting lies.”

Unsurprisingly ‘human rights’ campaigner Roger Waters calls the reality of Hamas raping Israelis on October 7 a “filthy lie”. Then he goes on to bizarrely reason with himself to calm down. Absolutely mad. Despicable. And dangerous. pic.twitter.com/fGFy7gogAU

— Heidi Bachram 🎗️ (@HeidiBachram) July 2, 2024

It’s not just that I still want to be able to listen to “Comfortably Numb” and (attempt to) play “Wish You Were Here” on my ukulele without feeling like I’m celebrating a Jew hater. I want to believe that the art we create is superior to the people we are—that when we create art, we are our best selves, better than the self we are outside of art.