Editor’s Note: The following essay first appeared in Areo Magazine in March 2017 and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

In this piece, Helen Pluckrose outlines some of the arguments later explored in depth in her bestselling 2020 book, Cynical Theories (co-authored with James Lindsay). The essay charts the pernicious influence of postmodernist thinking on two generations of academics and activists. If you want to understand how we got to a place where microaggressions are denounced as violence but the brutal terrorism of an intifada is considered righteous, this is an important primer.

—Iona Italia

Postmodernism presents a threat not only to liberal democracy but to modernity itself. That may sound like a bold or even hyperbolic claim, but the reality is that the cluster of ideas and values at the root of postmodernism have broken the bounds of academia and gained great cultural power in Western society. The irrational and identitarian symptoms of postmodernism are easily recognisable and much criticised, but the ethos underlying them is not well understood. This is partly because postmodernists rarely explain themselves clearly and partly because of the inherent contradictions and inconsistencies of a way of thought that denies that a stable reality or reliable knowledge exist. However, there are consistent ideas at the root of postmodernism and understanding them is essential if we intend to counter them. They underlie the problems we see today in Social Justice activism, undermine the credibility of the Left, and threaten to return us to an irrational and tribal premodern culture.

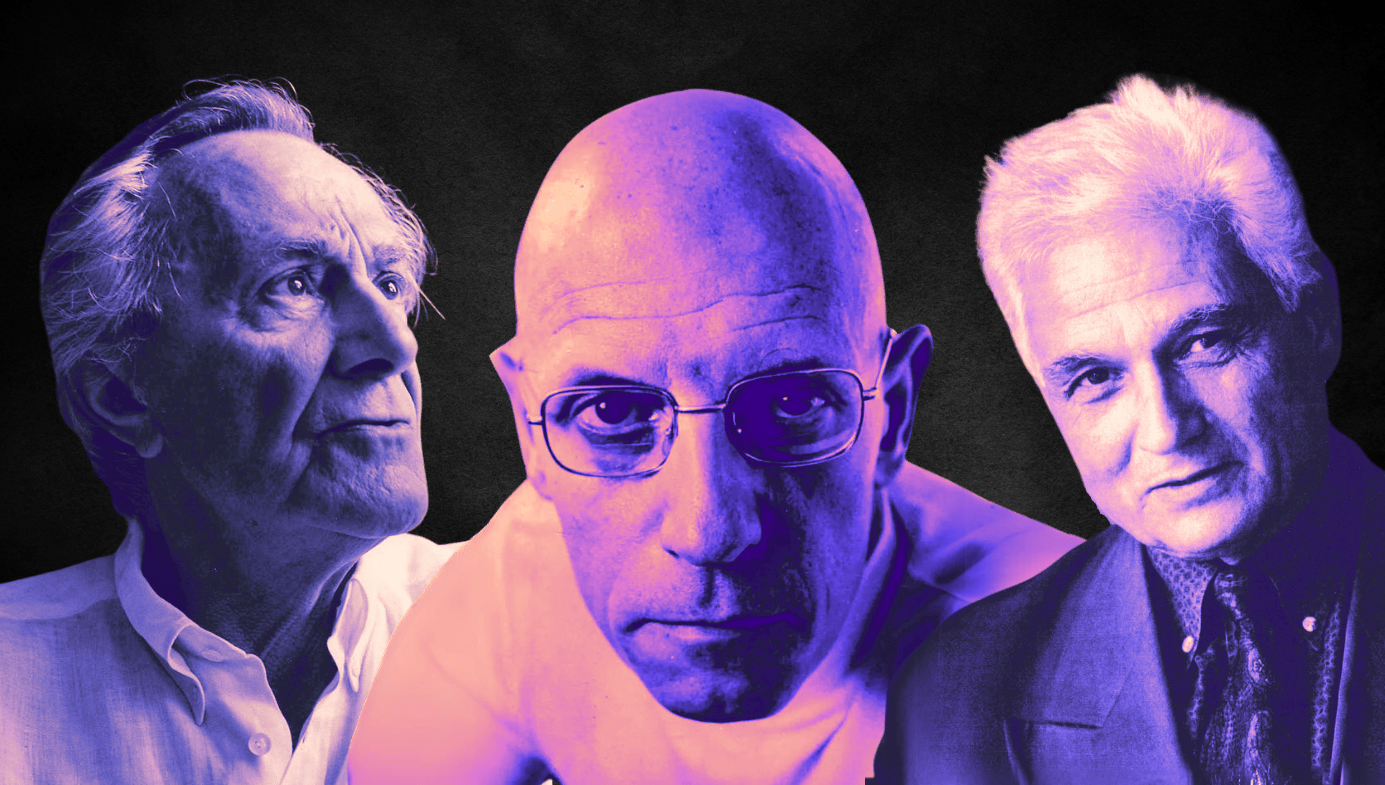

Postmodernism, most simply, is an artistic and philosophical movement, which began in France in the 1960s and produced bewildering art and even more bewildering theory. It drew on avant-garde and surrealist art and earlier philosophical ideas, particularly those of Nietzsche and Heidegger, for its anti-realism and rejection of the concept of the unified and coherent individual. It reacted against the liberal humanism of the modernist artistic and intellectual movements, which its proponents saw as naïvely universalising a Western, middle-class, and male experience.

It rejected philosophy, which valued ethics, reason, and clarity, with the same accusation. Structuralism, a movement which (often over-confidently) attempted to analyse human culture and psychology according to consistent structures of relationships, came under attack. Marxism, with its understanding of society through class and economic structures, was regarded as equally rigid and simplistic. Above all, postmodernists attacked science and its goal of attaining objective knowledge about a reality that exists independently of human perceptions, which they saw as merely another form of constructed ideology dominated by bourgeois, Western assumptions.

Above all, postmodernists attacked science and its goal of attaining objective knowledge about a reality that exists independently of human perceptions, which they saw as merely another form of constructed ideology dominated by bourgeois, Western assumptions.

Decidedly left-wing, postmodernism had both a nihilistic and a revolutionary ethos, which resonated with a post-war, post-empire zeitgeist in the West. As postmodernism continued to develop and diversify, its initially stronger nihilistic deconstructive phase became secondary (but still fundamental) to its revolutionary identity politics phase.