Art and Culture

Desire and Ambition

Today, most of John Braine’s work is out of print and forgotten. But he was an underrated writer, unafraid to confront the complexities of masculine sexuality with terse precision, self-deprecation, and emotional candour.

John Braine was born 102 years ago today, a couple of months before Kingsley Amis (whose 100th birthday was celebrated here). Yet while Amis has remained a part of the British literary consciousness, Braine has fallen into comparative obscurity. Today, he is remembered chiefly—and perhaps only—for his debut novel, Room at the Top.

In the mid-to-late ’50s, Braine and Amis would be lumped together as part of the Angry Young Men movement—a group of (mostly working-class and left-wing) upstarts from the sticks who filled the literary silence left by Oxbridge and Bloomsbury. Although he was both a Londoner and an Oxford graduate, Amis started the decade’s provincial wave with Lucky Jim (1953), which follows the social buccaneering of Jim Dixon, an irreverent assistant professor at a provincial university. Both Amis and Braine would springboard from their debut offerings into a wide readership and coveted literary celebrity. Both men would remain prolific writers of wavering quality, and in their later years, both ended up as right-wing, overweight alcoholics, serial polygamists, rueful divorcees, and faithful attendees of the weekly “Fascist Beast Luncheon Group” at Bertorelli’s in Soho.

His politically incorrect views notwithstanding, Amis managed to spin a successful late literary career that now survives in Penguin Vintage editions, an 11th-hour Booker win, two biographies, published letters, and a place within the canon. Braine’s later work, meanwhile, would suffer from his rigid political commitments and his deficiencies in nomenclature (Amis would grumble that Braine gave his characters ridiculous names like Clive Lendrick, Noll Mainton, or Jack Uplyme).

Today, most of Braine’s work is out of print, he has never had a biographer, and he failed to find a buyer for his diaries and notes. He ended up poor despite his dream of someday driving “through Bradford in a Rolls Royce with two naked women covered in jewels.” In 1985, he spent his last Christmas eating dinner at a community centre. The following year, at the age of 64, John Braine died from a gastric haemorrhage.

John Gerrard Braine was born in Bradford on April 13, 1922, the son of a corporation sewage-treatment supervisor who had worked in the wool mills as a child. What distinguished John Braine from his working-class surroundings—and from fellow Angries, Stan Barstow and Alan Sillitoe—was that, like Amis, he came from a literate, lower-middle-class household: Braine’s mother, Katherine, was a librarian before her marriage, and his father was a literary autodidact, having won several magazine short-story competitions.

But Braine’s second-act literary success (publishing Room at the Top at 33) was bookended by struggle and disappointment. He took a zigzag approach towards a career, failing to complete his school certificate at 16, and found menial work as an assistant in a bookshop, a furniture shop, and a laboratory, before finally settling at a library. That role was interrupted by the advent of the Second World War, when Braine trained as a navy telegraphist in a “melancholy and hideous collection of huts” in rural Hampshire.

Braine later stated that he hoped the war would provide his life with “purpose,” a “promise of change,” and an opportunity to fill his pockets with money “to take girls out,” but a tubercular patch on his lungs ensured that he never saw conflict. He would spend five months and his 22nd birthday in an isolation hospital in the Yorkshire Dales before returning to the library, completing his school certificate the same year, and then his librarian exam at 27 (after failing four times). All the while, he was gaining the life experiences that would inform his literary career.

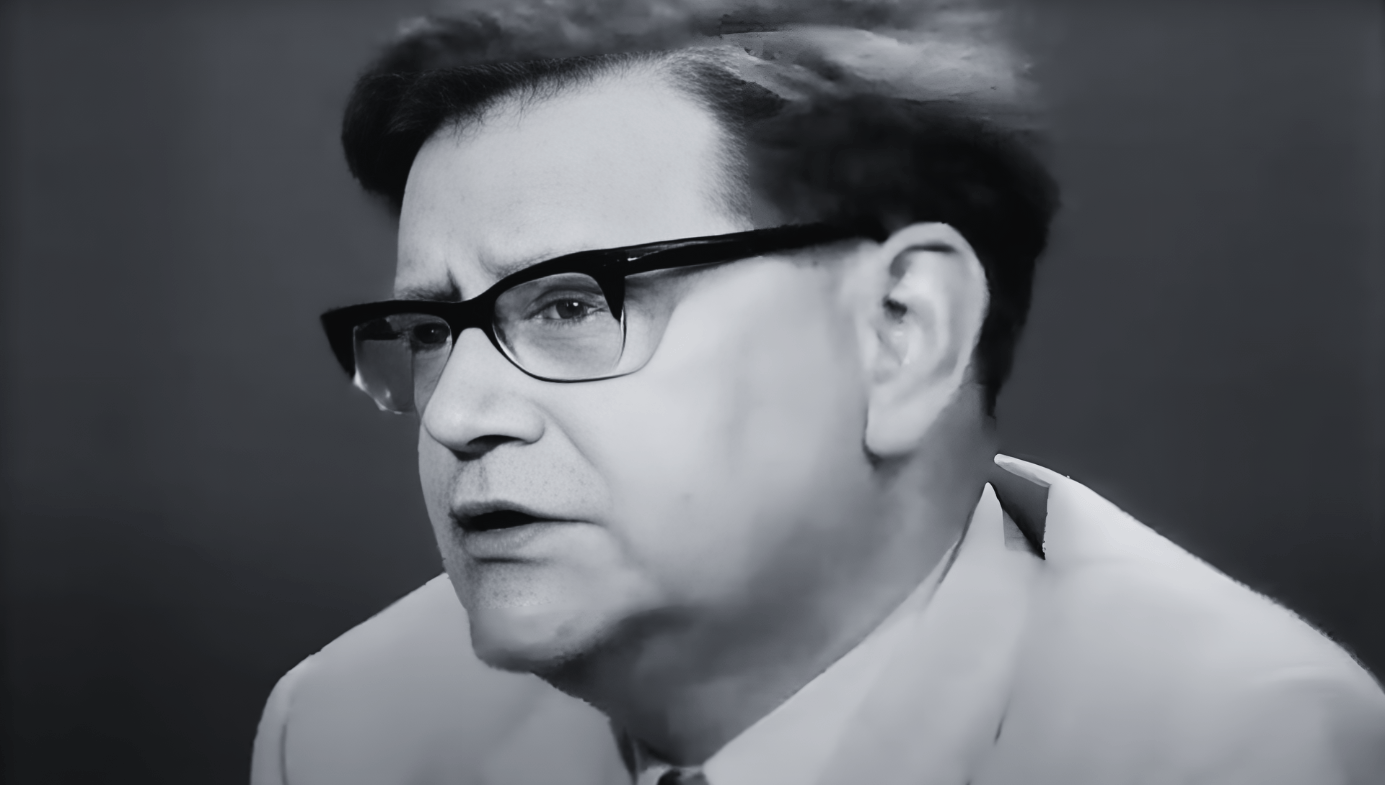

Like Joseph Lampton in Room at the Top, when Braine returned from convalescence, he discovered the hotbed world of local am-drams, where he would meet the girl who became the novel’s Susan Brown character. She was beautiful and—better still—upper-class: a colonel’s daughter. However, unlike Joe Lampton, Braine was not conventionally attractive (he was once described by Amis as “pale, bespectacled, chubby, with a perpetual look of being out of condition”). Braine nevertheless succeeded in taking the girl’s virginity. He planned to marry her but felt class-conscious inadequacy as a mere provincial librarian.

With £150 to his name, Braine made his way to London, where a few articles he’d published in small labour journals had caught the attention of literary agent Paul Scott. While he worked on his first novel, Braine sold the odd article to the New Statesman and occasionally broadcast on the BBC. Freelancer rates, however, barely covered his rent. In an interview with Kenneth Allsop for the latter’s rushed but useful account of the 1950s, The Angry Decade, Braine notes that in the underworld of “the bedsitter” where “men and women wander … muttering to themselves,” he “learned what it was like to be lonely, to come home to a solitary meal of a boiled egg and a cup of coffee made over a gas ring.”

Things would get worse before they got better. In 1951, his outline of a novel called Joe for King was rejected, his mother was killed when she walked in front of a bus, and he developed acute laryngitis and then a second bout of tuberculosis. He was—as he put it—“shipped back to Bradford on a train” where he spent the next 18 months in the same isolation hospital as before. The colonel’s daughter wrote to tell him she was getting married—to someone in her own social set.